|

|

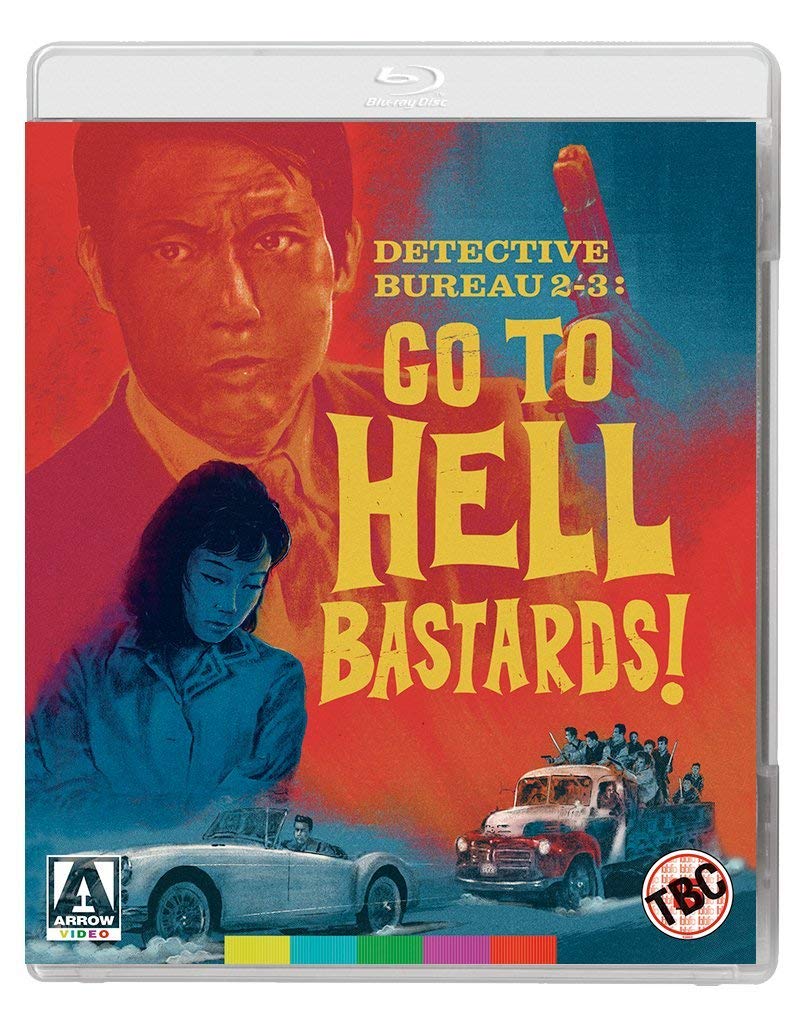

Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell Bastards AKA Tantei jimusho 23: Kutabare akuto-domo (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (17th July 2018). |

|

The Film

Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell, Bastards! (Suzuki Seijun, 1963) Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell, Bastards! (Suzuki Seijun, 1963)

Private investigator Tajima (Shishido Jo) works for Detective Bureau 2-3, alongside his two eccentric colleagues. When an exchange taking place between two yakuza gangs (the Sakura and Otsuki clans), and involving a truckload of guns taken from a US army base, is interrupted by gunfire from a third group travelling in a Pepsi Cola truck, the police – led by Captain Kumagai (Kaneko Nobuo) – seek Tajima’s help in identifying the attackers. Their only lead is Manabe (Kawaji Tamio), a low-ranking yakuza who the police have arrested but who is soon to be released owing to a lack of evidence. Kumagai asks Tajima to go undercover – as a PI, Tajima is less likely to be recognised than an undercover police officer – and assume the identity of Tanaka Ichiko, a hoodlum who is currently serving time in prison. The plan is for Tajima to earn the trust of Manabe, inveigling himself into the gang with which Manabe is associated, and investigate the crime from within. When Manabe is released by the police, Tajima helps the hood run the gauntlet of yakuza from the Sakura and Otsuki families, who have gathered outside with the intention of assassinating Manabe. Manabe takes Tajima back to his gang’s hideout, a garage above which sits a nightclub. There, Tajima is held hostage by Manabe’s associates, led by the sleazy Hatano (Shin Kinzo), whilst they investigate Tajima’s cover identity. Luckily, Tajima’s cover identity is bulletproof.  Tajima also meets Chiaki (Sassamori Reiko), the much younger lover of Hatano. With the aid of Sally (Hoshi Naomi), an old flame who works as a dancer in the nightclub atop the garage, Tajima passes messages to the police and his colleagues in Detective Bureau 2-3. Tajima becomes aware that Hatano’s gang is involved in transporting narcotics – but he must investigate exactly how they are managing to do this without being detected. Tajima is also asked by Chiaki to help her escape from Hatano: Chiaki reveals that the garage that the gang use as a hideout was once owned by her father, who was killed by Hatano. Tajima also meets Chiaki (Sassamori Reiko), the much younger lover of Hatano. With the aid of Sally (Hoshi Naomi), an old flame who works as a dancer in the nightclub atop the garage, Tajima passes messages to the police and his colleagues in Detective Bureau 2-3. Tajima becomes aware that Hatano’s gang is involved in transporting narcotics – but he must investigate exactly how they are managing to do this without being detected. Tajima is also asked by Chiaki to help her escape from Hatano: Chiaki reveals that the garage that the gang use as a hideout was once owned by her father, who was killed by Hatano.

However, Hatano becomes aware of Tajima’s real identity and sets a trap for both the private investigator and Manabe, who has become a liability in other ways. Tajima must find a way of escaping from Hatano’s grasp whilst also revealing the secret of the gang’s involvement in the trade in narcotics. Nikkatsu’s mukokuseki akushon (‘borderless action’) pictures of the 1960s offered an attempt by the studio to appeal to a youth market by taking influences (both thematic and visual, in terms of their use of chiaroscuro lighting and obtuse angles and compositions) from American films noir, the youth films popular during the 1950s and 1960s, American ‘adult’ Westerns of the 1950s and, in later examples of the form’s ‘Servant of Two Masters’-type plots, westerns all’italiana like Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars (1964). Nikkatsu’s action pictures of this period had an ‘international’ flavour that led to them being labelled as ‘borderless’ action films (mukokuseki akushon), and the pictures themselves were predominantly tailored towards a young audience.  Nikkatsu’s trend in producing youth-oriented mukokuseki akushon pictures began in 1956 with Furukawa Takumi’s Season of the Sun. Drawing from European and American cinema, the films borrowed something of the individualism and film noir sensibility of American films and mixed it with the experimentation and existential dilemmas found within many European ‘New Wave’ cinemas. This was heightened in the 1960s, a time when some of the filmmakers within the Nikkatsu ‘stable’ demonstrated a strong sense of invention: Suzuki Seijun is possibly the most famous example, given the outrageous experimentation within his anarchic 1967 picture Branded to Kill which led to him being fired by Nikkatsu. Having worked as a director for Nikkatsu since his debut feature Victory is Mine in 1954, Suzuki was hired to direct Branded to Kill at the last minute and turned in a picture that, to Nikkatsu’s bosses, was deliberately ‘incomprehensible’ (Sharp, 2011: 182). Branded to Kill may be considered a subversive self-parody of the mukokuseki akushon pictures; Nikkatsu terminated Suzuki’s contract illegally, and when Suzuki struck back by suing Nikkatsu, leading to him being effectively blacklisted for the next ten years, he consolidated his position as a countercultural figure. Nikkatsu’s trend in producing youth-oriented mukokuseki akushon pictures began in 1956 with Furukawa Takumi’s Season of the Sun. Drawing from European and American cinema, the films borrowed something of the individualism and film noir sensibility of American films and mixed it with the experimentation and existential dilemmas found within many European ‘New Wave’ cinemas. This was heightened in the 1960s, a time when some of the filmmakers within the Nikkatsu ‘stable’ demonstrated a strong sense of invention: Suzuki Seijun is possibly the most famous example, given the outrageous experimentation within his anarchic 1967 picture Branded to Kill which led to him being fired by Nikkatsu. Having worked as a director for Nikkatsu since his debut feature Victory is Mine in 1954, Suzuki was hired to direct Branded to Kill at the last minute and turned in a picture that, to Nikkatsu’s bosses, was deliberately ‘incomprehensible’ (Sharp, 2011: 182). Branded to Kill may be considered a subversive self-parody of the mukokuseki akushon pictures; Nikkatsu terminated Suzuki’s contract illegally, and when Suzuki struck back by suing Nikkatsu, leading to him being effectively blacklisted for the next ten years, he consolidated his position as a countercultural figure.

Reflecting their ‘borderless’ qualities, Nikkatsu’s mukokuseki akushon films featured individualistic heroes, often gangsters or policemen (or in the case of Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell, Bastards!, private eyes), who drank whisky in jazz clubs and skulked through scenes shot in film noir-esque chiaroscuro lighting. In previous Japanese films, the yakuza had appeared - but usually in jidaigeki pictures (period dramas). In earlier yakuza films, the villains were often Westernised, and in contrast with these Westernised characters the moral code of the yakuza would usually be depicted in a positive light. Nikkatsu’s borderless action films, with their contemporary urban settings and their morally-conflicted and Westernised heroes (rather than villains), were in stark contrast with these earlier yakuza pictures. However, as Jasper Sharp has noted, despite their modern-day settings, the mukokuseki akushon pictures ‘bore little resemblance to any contemporary Japanese reality’ (Sharp, 2011: 182).  A strong example of mukokuseki akushon (Shishido Jo’s Westernised protagonist, a private investigator, wears a Humphrey Bogart-esque trenchcoat and drives an imported open top sports car), Suzuki’s 1963 film Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell, Bastards! marked the end of one period of the career of its director: in Suzuki’s next film, Youth of the Beast (1963), Suzuki would demonstrate a willingness to push the boundaries of the genre stylistically that escalated throughout his subsequent films (such as Kanto Wanderer, 1963), culminating in Suzuki’s conflict with Nikkatsu over Branded to Kill. Detective Bureau 2-3 was also the first film that Suzuki made with the actor Shishido Jo, the star of Branded to Kill (Youth of the Beast was the second of these collaborations). A strong example of mukokuseki akushon (Shishido Jo’s Westernised protagonist, a private investigator, wears a Humphrey Bogart-esque trenchcoat and drives an imported open top sports car), Suzuki’s 1963 film Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell, Bastards! marked the end of one period of the career of its director: in Suzuki’s next film, Youth of the Beast (1963), Suzuki would demonstrate a willingness to push the boundaries of the genre stylistically that escalated throughout his subsequent films (such as Kanto Wanderer, 1963), culminating in Suzuki’s conflict with Nikkatsu over Branded to Kill. Detective Bureau 2-3 was also the first film that Suzuki made with the actor Shishido Jo, the star of Branded to Kill (Youth of the Beast was the second of these collaborations).

The ‘borderless’ quality of Detective Bureau 2-3 is established in the opening sequence, in which yakuza hoods are driving a US army truck loaded with guns stolen from the American military. They are ushered out of the compound by a black American GI, and they take the guns to a location where they are, apparently, intending to sell them to members of another yakuza family. However, the deal is interrupted before it can go down by a Pepsi Cola truck from which another gangster fires a machine gun, killing a number of yakuza and causing the vehicles involved in the exchange to burst into flames. There are shades of James Bond in the main plot, with Tajima’s task essentially being one of espionage. (At several points in the film, Hatano and his cronies accuse Tajima of being a ‘spy’.) The stakes are raised when Kumagai promises that any transgressions enacted by Tajima whilst he is undercover will result in the police distancing themselves from Tajima: ‘You’re the bait’, Kumagai tells our hero, ‘But if you ever break the law, I’ll throw you in jail’.  In the midst of this story are some eccentric moments: Manabe’s relationship with his girlfriend is chief among these. After Tajima has helped Manabe escape the Sakura and Otsuki clans, following Manabe’s release from prison, Manabe visits his lover. Suzuki stages this sequence eccentrically, offering hints of the stylisation associated with his later yakuza pictures: the apartment is bathed alternately in vibrant yellow and deep crimson light, the use of coloured gels in this sequence resembling Mario Bava’s use of coloured light in, for example, Sei donne per l’assassino (Blood and Black Lace, 1964). ‘Bitch!’, is Manabe’s greeting for his girlfriend, ‘Why didn’t you visit me in prison?’ Manabe then accuses her of infidelity before the pair engage in some almost sadomasochistic lovemaking. The behaviours in this sequence are repeated later, towards the end of the film, after Tajima has once again helped Manabe escape almost certain death, in a trap set for the pair by Hatano: Manabe returns to the apartment and, again, accuses his lover of infidelity before, again, initiating some rough sex. (However, this time the pair are killed, shot to death by an unseen assailant.) This pair of scenes hints at a theme that runs throughout the film, and which links sex with violence: Hatano, Chiaki tells Tajima, is impotent, and therefore Chiaki – for whom Hatano was her first and only lover – is still a virgin. Hatano’s impotence, the film suggests, is a root cause of his venal violence. Regressively, but in line with the conventions of film noir in particular, Chiaki’s status as a ‘pure’ woman makes her ‘worthy’ of being rescued from the gang by Tajima – like a kidnapped princess in a folk tale of yore. The repression of the gangsters is contrasted by Tajima’s vivacity: when he dances and sings in the nightclub with his former lover Sally, Hatano comments with disgust, ‘What vulgarity! He’s different from us’. In the midst of this story are some eccentric moments: Manabe’s relationship with his girlfriend is chief among these. After Tajima has helped Manabe escape the Sakura and Otsuki clans, following Manabe’s release from prison, Manabe visits his lover. Suzuki stages this sequence eccentrically, offering hints of the stylisation associated with his later yakuza pictures: the apartment is bathed alternately in vibrant yellow and deep crimson light, the use of coloured gels in this sequence resembling Mario Bava’s use of coloured light in, for example, Sei donne per l’assassino (Blood and Black Lace, 1964). ‘Bitch!’, is Manabe’s greeting for his girlfriend, ‘Why didn’t you visit me in prison?’ Manabe then accuses her of infidelity before the pair engage in some almost sadomasochistic lovemaking. The behaviours in this sequence are repeated later, towards the end of the film, after Tajima has once again helped Manabe escape almost certain death, in a trap set for the pair by Hatano: Manabe returns to the apartment and, again, accuses his lover of infidelity before, again, initiating some rough sex. (However, this time the pair are killed, shot to death by an unseen assailant.) This pair of scenes hints at a theme that runs throughout the film, and which links sex with violence: Hatano, Chiaki tells Tajima, is impotent, and therefore Chiaki – for whom Hatano was her first and only lover – is still a virgin. Hatano’s impotence, the film suggests, is a root cause of his venal violence. Regressively, but in line with the conventions of film noir in particular, Chiaki’s status as a ‘pure’ woman makes her ‘worthy’ of being rescued from the gang by Tajima – like a kidnapped princess in a folk tale of yore. The repression of the gangsters is contrasted by Tajima’s vivacity: when he dances and sings in the nightclub with his former lover Sally, Hatano comments with disgust, ‘What vulgarity! He’s different from us’.

The film’s narrative is relatively straight-forward and, arguably, no great shakes. However, Shishido proves himself to be a charismatic lead, and Suzuki invests the material with pre-tremors of the stylistic flourishes that would make his later films in this genre so notable, including some carefully choreographed nightclub scenes that wouldn’t look out of place in a Jean-Pierre Melville film of the late 1960s. (In one of these, Tajima joins an old flame, Sally, on stage for an impromptu duet; in another, girls dressed in bikinis and Father Christmas hats are shown dancing around a huge Christmas tree bedecked in tinsel whilst a jazz rendition of ‘When the Saints Go Marching In’ is played.) Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell, Bastards! was the first in a planned series of films for Nikkatsu; it was followed by Detective Bureau 2-3: A Man Weak to Money and Women (Yanase Nozumu, 1963), also starring Shishido Jo. No further instalments were made.

Video

The film takes up just over 23Gb of space on its Blu-ray disc. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec, and the film runs for 88:08 mins. Presented in its intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1 (and photographed anamorphically, in Nikkatsuscope, on 35mm colour stock), Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell, Bastards! fares well on Arrow Video’s new Blu-ray release. Colours are tight, consistent and stable – especially in those sequences which feature expressionistic use of red and yellow coloured gels on the lights. A pleasing level of detail is present throughout the presentation, and with much of the film seemingly being shot with shorter focal lengths (complete with barrel distortion that becomes especially noticeable when the camera is mobile), there is a good sense of depth to the image. There is no damage to speak of. Midtones are solid and defined, and shadows taper off nicely to the toe. The film takes up just over 23Gb of space on its Blu-ray disc. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec, and the film runs for 88:08 mins. Presented in its intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1 (and photographed anamorphically, in Nikkatsuscope, on 35mm colour stock), Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell, Bastards! fares well on Arrow Video’s new Blu-ray release. Colours are tight, consistent and stable – especially in those sequences which feature expressionistic use of red and yellow coloured gels on the lights. A pleasing level of detail is present throughout the presentation, and with much of the film seemingly being shot with shorter focal lengths (complete with barrel distortion that becomes especially noticeable when the camera is mobile), there is a good sense of depth to the image. There is no damage to speak of. Midtones are solid and defined, and shadows taper off nicely to the toe.

Some full-sized screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review; please click to enlarge them.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 track, in Japanese, with optional English subtitles. The audio track is rich and deep, with good range and no noticeable distortion. The subtitles are easy to read and free from grammatical errors.

Extras

The disc includes: - ‘Tony Rayns on Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell, Bastards!’ (28:57). Rayns delivers an engaging half hour of information. Characteristically well-researched, Rayns’ comments examine the production of the film, its themes, and situate it within the careers of its key personnel. - Stills Gallery

Overall

Though not as inventive as Suzuki’s later yakuza pictures, Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell, Bastards! is a solid, entertaining example of Nikkatsu’s ‘borderless’ pictures of the early 1960s, with its Westernised private investigator hero who wanders through nightclubs and double crosses in his quest to nail the yakuza gang. There are some visually interesting sequences, and Shishido Jo proves himself to be a very charismatic lead actor – something that Suzuki would admittedly exploit much more effectively in Youth of the Beast and Branded to Kill. It’s a fast-paced film that doesn’t outstay its welcome. Though not as inventive as Suzuki’s later yakuza pictures, Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell, Bastards! is a solid, entertaining example of Nikkatsu’s ‘borderless’ pictures of the early 1960s, with its Westernised private investigator hero who wanders through nightclubs and double crosses in his quest to nail the yakuza gang. There are some visually interesting sequences, and Shishido Jo proves himself to be a very charismatic lead actor – something that Suzuki would admittedly exploit much more effectively in Youth of the Beast and Branded to Kill. It’s a fast-paced film that doesn’t outstay its welcome.

Arrow Video’s new Blu-ray release of Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell, Bastards! contains a pleasing presentation of the film that is supported by an interview with Tony Rayns which helps to situate provide this picture with a strong sense of context. References: Desjardins, Chris, 2005: Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film. London: I B Tauris Jacoby, Alexander, 2008: A Critical Handbook of Japanese Film Directors: From the Silent Era to the Present Day. California: Stonebridge Press Schilling, Mark, 2007: No Borders, No Limits: Nikkatsu Action Cinema. Godalming: FAB Press Sharp, Jasper, 2011: Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema. Maryland: Scarecrow Press Click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|