|

|

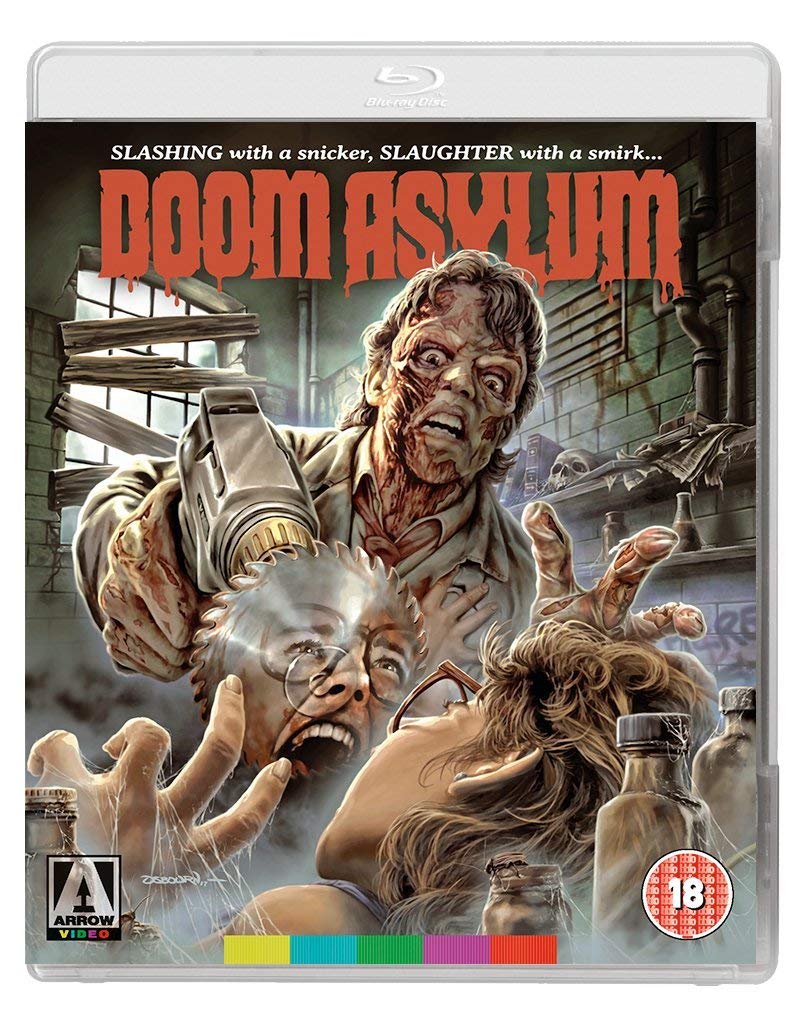

Doom Asylum (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (18th July 2018). |

|

The Film

Doom Asylum (Richard Friedman, 1987) Doom Asylum (Richard Friedman, 1987)

Sleazy lawyer Mitch (Michael Rogen) and his lover Judy LaRue (Patty Mullen) are celebrating after winning a large sum of money in a court case – presumably from Judy’s ex-husband. Judy has left her daughter behind, and the couple are driving through country roads in Mitch’s convertible whilst swigging champagne. Mitch crashes the car, however, and Judy is killed. Mitch is left nursing his lover’s severed hand, and he too appears to expire. An autopsy is performed, but Mitch isn’t quite dead. He awakens, attacking and killing both the doctor and his assistant. Ten years later, a car load of young people travel along the same road. The car carries Darnell (Harrison White), whose name we know because he handily wears it on chain around his neck; baseball card fan Dennis (Kenny L Price); Jane (Kristin Davis, later of Sex and the City), who spouts psychoanalytic theory at every given opportunity; Mike (William Hay), who shows himself to be deeply indecisive; and his lover Kiki (also played by Patty Mullen), who happens to be the daughter of Judy. They are heading to an abandoned hospital for an unspecified reason (a picnic?) and mock the ‘old story’ of the place: ‘A man who lurks in a deserted asylum and kills people with autopsy tools? Sure!’ At the hospital, the young people find an all-woman punk band, Tina and the Tots, rehearsing. The band consists of Tina (Ruth Collins), Rapunzel (Farin) and Godiva (Dawn Alvan). At first, Tina and the Tots come into conflict with Kiki’s group of friends, but eventually the ghoulish Mitch begins to pick off members both groups one by one, as they wander away from their respective herds. Using various medical instruments (forceps, a bone saw, etc) to dispatch his victims, Mitch is eventually forced to confront the very image of the woman he once loved, in the form of her daughter, Kiki.  Made independently and really, really cheaply – I mean really cheaply – Doom Asylum is a mixture of stalk-and-slash/splatter picture and horror-comedy. Some of the gore effects are good, though Mitch’s face looks like the rubber mask that it is, and the humour is weak sauce, but nevertheless the film has a strange, indefinable charm. Some of this perhaps comes from its atmospheric location (the film was shot in a real abandoned hospital, the Essex Mountain Sanatorium), which the filmmakers use to their advantage by shooting down backlit corridors in which one constantly expects a shadow to appear at the end, or framing the action through broken panes of glass. Made independently and really, really cheaply – I mean really cheaply – Doom Asylum is a mixture of stalk-and-slash/splatter picture and horror-comedy. Some of the gore effects are good, though Mitch’s face looks like the rubber mask that it is, and the humour is weak sauce, but nevertheless the film has a strange, indefinable charm. Some of this perhaps comes from its atmospheric location (the film was shot in a real abandoned hospital, the Essex Mountain Sanatorium), which the filmmakers use to their advantage by shooting down backlit corridors in which one constantly expects a shadow to appear at the end, or framing the action through broken panes of glass.

The film’s associate producer, Ted Hope, reflected in his autobiography that Doom Asylum originated when he was called by a rep from the production company Films Around the World, who told Hope ‘We have to come up with a movie we can completed in ten days: Find a location we can shoot in, and find people we don’t have to pay much. We don’t have a script, we don’t have a cast, but we’re going to shoot it in four weeks from now regardless’ (Hope, 2014: 14-5). Locations were scouted, and a decision was made to shoot the picture in the Essex Mountain Sanatorium, which had been abandoned about a decade earlier. ‘Basically, we were just running people up and down the halls’, Hope reflected (ibid.: 15). Ultimately, Hope suggests, Doom Asylum ‘was an exercise in how to get a movie made with as little available as possible’ (ibid.). The film features some risible filmmaking techniques (the opening car crash is communicated simply by a shaky camera and a cut to the aftermath) alongside some quite atmospheric sequences (for example, point-of-view shots as Mitch wanders the service corridors beneath the hospital). The eccentric characters (baseball card-collecting Dennis is particularly memorable) are matched by camp dialogue that strains for laughs but doesn’t always get them (various characters refer to Tina as ‘torpedo tits’ owing to her Madonna-style conical bra). The acting is often atrocious too: in the scene in which an autopsy is almost performed on Mitch, the coroner stands over Mitch’s badly mutilated body – whilst, like all good coroners, wearing his sunglasses inside – and, in between bites of his sandwich, tells his assistant, ‘Relax, kid. You seen one of these, you seen ‘em all’. Mitch rises from the slab and advances on the coroner’s assistant, who mutters ‘Please, no’, with all the urgency of a man who has realised he’s ordered the wrong meal in a restaurant. Amidst this is some utterly unnecessary nudity, the filmmakers making use of the fact that both Ruth Collins and Patty Mullen were centrefold girls – and Mullen spends most of the film running from Mitch whilst wearing nothing more than a skimpy tomato red bikini and matching high heels.  The film has some moments of utter… weirdness. At the start of the film, Mike attempts to console Kiki after she miraculously finds her mother’s handmirror at the side of the road (no less than ten years after her mother’s fatal car accident). ‘After all, you’ve got me now’, he tells her, ‘If that’s any comfort to you. I’m not your mother, and I never could be. [No shit, Sherlock, the viewer might be thinking.] But I can try’. ‘Can I call you “mom”?’ Kiki asks, to which Mike responds, ‘Sure’. From this point in the film onwards, Kiki insists bizarrely on calling her lover ‘Mom’. Elsewhere, there are other bizarre moments, such as when Mitch attacks one of the members of Tina and the Tots, and in response she apathetically begs, ‘I’m just a female. I’m your sister […] The use of violence requires more violence. No! I’m a Republican. I voted for Reagan. No!’ (In response, Mitch dunks her head in a sink filed with industrial acid cleaner and asserts, ‘I respect your First Amendment rights to the political beliefs of your choice, but I don’t necessarily agree’.) In an equally strange moment of dialogue, Mike and Kiki take a break from fleeing from Mitch and kneel at the altar of the ruined hospital’s chapel, Kiki pleading with God: ‘I just want to add, God, that if we make it out, I’ll give you anything you want. Money, sex, a charge card at Bloomey’s…’. The film has some moments of utter… weirdness. At the start of the film, Mike attempts to console Kiki after she miraculously finds her mother’s handmirror at the side of the road (no less than ten years after her mother’s fatal car accident). ‘After all, you’ve got me now’, he tells her, ‘If that’s any comfort to you. I’m not your mother, and I never could be. [No shit, Sherlock, the viewer might be thinking.] But I can try’. ‘Can I call you “mom”?’ Kiki asks, to which Mike responds, ‘Sure’. From this point in the film onwards, Kiki insists bizarrely on calling her lover ‘Mom’. Elsewhere, there are other bizarre moments, such as when Mitch attacks one of the members of Tina and the Tots, and in response she apathetically begs, ‘I’m just a female. I’m your sister […] The use of violence requires more violence. No! I’m a Republican. I voted for Reagan. No!’ (In response, Mitch dunks her head in a sink filed with industrial acid cleaner and asserts, ‘I respect your First Amendment rights to the political beliefs of your choice, but I don’t necessarily agree’.) In an equally strange moment of dialogue, Mike and Kiki take a break from fleeing from Mitch and kneel at the altar of the ruined hospital’s chapel, Kiki pleading with God: ‘I just want to add, God, that if we make it out, I’ll give you anything you want. Money, sex, a charge card at Bloomey’s…’.

In an obvious attempt to pad out the slender running time, Doom Asylum returns time and time again to shots of Mitch watching old Tod Slaughter movies on a television in one of the hospital’s rooms. Chunks of the film are taken up with inexplicably lengthy cut-ins to these Tod Slaughter movies, and the viewer is left wondering how Mitch can be prowling through the hospital corridors one minute, then return to watching his Tod Slaughter pictures the next, before being seen once again prowling through the hospital corridors and committing wanton acts of murder. Does he stop off after every ten minutes of stalking the hospital corridors to watch short extracts from 1930s British horror films? Are the filmmakers suggesting that Mitch’s murderous impulses have been catalysed by watching old Tod Slaughter films? Is he killing the young people who stray into the building because they are disturbing his enjoyment of these movies? Who knows.

Video

Doom Asylum is here presented in 1080p (using the AVC codec), uncut and with a running time of 78:46 mins. Doom Asylum is here presented in 1080p (using the AVC codec), uncut and with a running time of 78:46 mins.

Though ultimately a straight-to-video release, Doom Asylum was apparently produced with theatrical distribution in mind. As a consequence, the film’s director of photography, Larry Revene, composed the picture with a 1.85:1 (or thereabouts) framing in mind. However, released directly to video, Doom Asylum was seen by most viewers in an open matte presentation at 1.33:1: this presentation opened up the top and bottom of the framing but lost a little information at the left and right-hand sides of the frame. By opening up the top and bottom of the frame, extraneous details not meant to be seen by the audience (for example, boom mics) would occasionally drift into the compositions, adding to the overall slapdash feel of the production. Arrow Video’s new Blu-ray release of Doom Asylum offers two ways to view the picture: via (i) a 1.78:1 presentation which mimics that intended by the director of photography; and (ii) a 1.33:1 presentation that mimics how the film looked on home video. The 1.33:1 presentation opens up a little more of the frame than the old VHS releases, however, with less cropping on the left and right-hand edges of the frame than the previous fullframe videocassettes. The 1.78:1 presentation cuts in to 1.33:1 for the video-generated titles sequence, then returns back to 1.78:1 for the rest of the feature. The 1.78:1 presentation takes up just under 19Gb of space on the disc, and the 1.33:1 presentation fills a little over 20Gb of space. Doom Asylum was shot on 35mm colour stock. The presentation is sourced from a new 2k scan of the film’s negative. Colours are consistent and stable; a strong level of fine detail is present throughout the picture. Contrast levels are equally pleasing, with defined midtones being present, and good gradation into the toe. Damage is limited to a few small white flecks, except for a handful of shots – presumably from the same reel – which feature some damage on the right hand side of the frame (which looks like an area where the film has been overexposed or overdeveloped). Finally, a solid encode to disc ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film. Some full-sized screengrabs from both the 1.33:1 and 1.78:1 presentations are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 track, which is clear and free of problems. The track shows good range and dialogue is audible throughout. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included. These are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- A commentary with screenwriter Rick Marx, moderated by Howard Berger. The pair discuss the production history of the film, reflecting on the role of its production company, Films Around the World. Marx talks about how he came to write the picture, and the approach of the filmmakers was that slasher films had an ‘inherent ridiculousness’ and that by accepting this, ‘we could say anything we wanted’. It’s an interesting commentary track, with Berger prompting Marx’s recollection, and it’s well worth a listen – regardless of what one thinks of the film – thanks to the insight it provides into the world of independent filmmaking from which Doom Asylum grew. - A commentary with The Hysteria Continues. The ever-dependable Hysteria Continues podcast chaps provide an entertaining and fact-filled commentary for the picture. They talk about their first encounters with the film and discuss about the film’s makeup effects, admitting that whilst ‘some of them are pretty bad’, others are ‘excellent’. Doom Asylum is described in the track as ‘the kind of slasher film that John Waters would make’, and they argue that the film was made with its tongue firmly in its cheek. - ‘Tina’s Terror’ (17:56). In a new interview, Ruth Collins reflects on how she became an actress after a successful modelling career, and she talks about her time on the set of the film. Collins reveals that she wasn’t the first choice for the role of Tina: originally, the band in the film were to be played be a real, albeit male-dominated band, but the roles were recast and the band became Tina and the Tots. Collins talks about the challenges (and joys) in making such a low-budget film.

- ‘Movie Madhouse’ (19:00). Director of photography Larry Revene suggests the film was ‘designed to cover all the bases’ – in terms of onscreen nudity and violence. Revene reflects on his career to the point of the production of Doom Asylum. He states that the script didn’t have enough material to make a full feature film, and this was why the scenes involving Mitch watching Tod Slaughter films were introduced – to bring the film up to feature length. Revene discusses the location, which he says is ‘one of the strongest aspects of the film’, and says that the film represents ‘a free form shooting of certain things’ – unscripted scenes of the characters walking through the hospital, for example. The production enlisted a second unit to shoot ‘B’ roll-type footage, but this second unit didn’t produce much usable footage – and Revene suggests this was the biggest mistake made by the ‘neophyte’ filmmakers. - ‘Morgues & Mayhem’ (17:38). The creator of the film’s special makeup effects, Vincent J Guastini, talks about his work on the film. Guastini says that when Doom Asylum was made, he was ‘just starting out’ and was making his makeup effects ‘out of my mother’s pantry’. Tom Savini’s book Grande Illusions offered much of the inspiration for the film’s effects. Guastini discusses some of the difficulties he faced during the shoot, and states that he is particularly proud of the scene in which a drill penetrates a character’s head – which was achieved without any protective plates against the actor’s forehead. - Archival Interviews (10:56). These interviews with executive producer Alexander W Kogan, Jr, director Richard Friedman and production manager Bill Tasgal previously appeared on the US DVD release from Code Red. - Stills Gallery (3:05).

Overall

The narrative of Doom Asylum is illogical, and not in a way that can be kindly described as having the texture of a nightmare: it simply makes no sense. How did Mitch ignore the presence of the abominably loud punk group that has been rehearsing in the hospital, but becomes ‘active’ once Kiki and her friends arrive on the site for a picnic? Why is Kiki’s mother’s mirror still by the roadside ten years after her fatal car accident? The recurrent cutaways to Mitch watching Tod Slaughter films make no sense and appear at random – one minute Mitch is killing one of his victims, the next he’s in his room watching old horror films on a television, and in the next moment he’s back to prowling the hospital corridors looking for new victims. The narrative of Doom Asylum is illogical, and not in a way that can be kindly described as having the texture of a nightmare: it simply makes no sense. How did Mitch ignore the presence of the abominably loud punk group that has been rehearsing in the hospital, but becomes ‘active’ once Kiki and her friends arrive on the site for a picnic? Why is Kiki’s mother’s mirror still by the roadside ten years after her fatal car accident? The recurrent cutaways to Mitch watching Tod Slaughter films make no sense and appear at random – one minute Mitch is killing one of his victims, the next he’s in his room watching old horror films on a television, and in the next moment he’s back to prowling the hospital corridors looking for new victims.

There are some very good gore effects: a toe being sliced off whilst Mitch recites ‘This Little Piggy’; forceps being buried into a victim’s temples; another victim’s face is sliced open with a bone saw. However, the makeup effects for Mitch are less than effective, and his visage looks like the rubber mask that it is. (Some more inventive photography and lighting could have helped avoid this, to be honest.) The acting is often terrible, and the humour mostly falls flat. However, despite all this, the film has an indefinable charm. Some of this is sourced from the decision to shoot the picture in the Essex Mountain Sanatorium, which functions as an eerie backdrop to the onscreen action. Arrow’s presentation of the film is very good indeed. The decision to include the familiar 1.33:1 framing (from the film’s VHS releases) alongside a 1.78:1 framing closer to the intentions of the film’s director of photography, Larry Revene, is to be applauded. Additionally, there’s an excellent array of contextual material: the new interviews with Collins, Guastini and, particularly, Revene are excellent, as are the commentary tracks. References: Hope, Ted, 2014: Hope for Film: From the Frontline of the Independent Cinema Revolutions. Berkeley: Soft Skull Press Please click to enlarge: 1.33:1 presentation

1.78:1 presentation

1.33:1 presentation

1.78:1 presentation

1.33:1 presentation

1.78:1 presentation

1.33:1 presentation

1.78:1 presentation

1.33:1 presentation

1.78:1 presentation

1.33:1 presentation

1.78:1 presentation

1.33:1 presentation

1.78:1 presentation

1.33:1 presentation

1.78:1 presentation

1.78:1 presentation

|

|||||

|