|

|

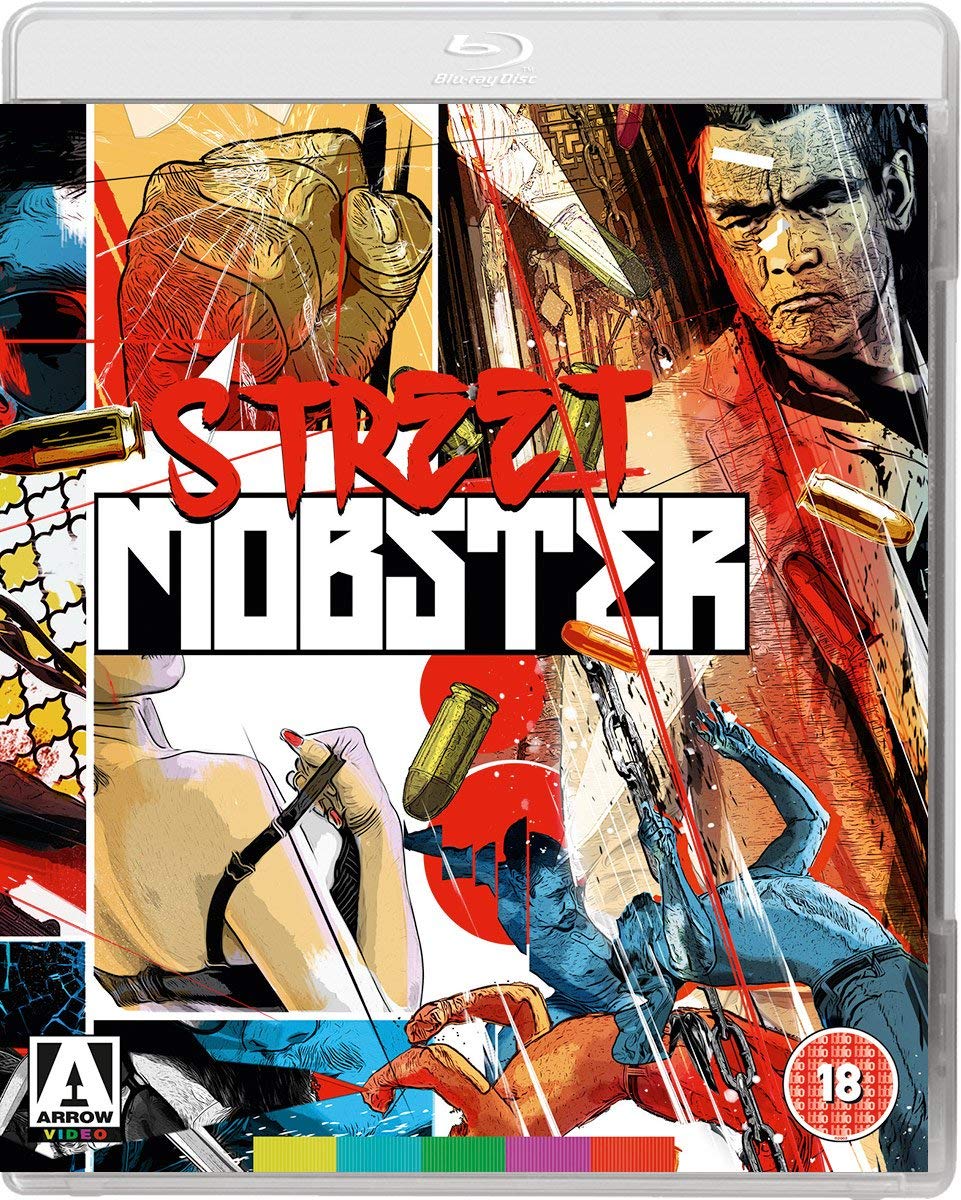

Street Mobster AKA Gendai yakuza: hito-kiri yota (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (13th August 2018). |

|

The Film

Street Mobster (Fukasaku Kinji, 1972) Street Mobster (Fukasaku Kinji, 1972)

Street punk Okita Isamu (Sugawara Bunta) was born on the wrong side of the tracks. The illegitimate son of a prostitute, Okita spent two spells in a reform school before leading his own street gang. After coming into conflict with the powerful Takigawa clan and raiding one of their bathhouses, Okita is thrown into jail where he makes an ally of the silent Taniguchi. When Okita and Taniguchi are released from prison at the same time, Okita asks Taniguchi to join him, but Taniguchi chooses instead to return to a proletarian life running a noodle shop with his wife. Alone in a Tokyo that is drastically different to the city that he remembers from before his incarceration, Okita soon comes into conflict with a group of street punks. After fighting them, he earns their respect, and they take him back to their hideout. There, Okita learns that the young men were previously controlled by Takigawa (Morozumi Keijiro) but were abandoned by him when they no longer served a purpose for the Takigawa clan. The street punks find a prostitute, Kimiyo (Nagisa Mayumi), for Okita. However, Kimiyo attacks Okita, revealing that when she first arrived in the city after having travelled from the countryside, Okita and his crew gang raped her and sold her to a brothel. Okita displays some regret and quietly apologises, and in a confusion of rage and desire Kimiyo kisses him passionately. Having been taken in by the gang of street punks as their de facto leader, Okita is soon confronted by another hoodlum, Kizaki. Kizaki has a proposition for Okita. The city is divided into territories held by the Takigawa family and those held by the Yato clan. Kizaki suggests that he and Okita lead the street punks and take over their own territory. Okita leads the street punks in a series of running battles with members of the Takigawa family, trashing the Takigawa properties. Somewhat surprisingly, the head of the Yato family (Ando Noboru) offers shelter to Okita and his street mobsters, clearly seeing in the fiercely independent Yato echoes of his own youth. However, Yato requires Okita to join the Yato family. Initially, Okita resists but soon realises this is his only option.  However, despite the new peace being an economic success for Okita and his street punks, Okita finds it boring; he misses the violence of the era before his alliance with the Yato family. He makes conflict in his personal life by being unfaithful towards Kimiyo. However, despite the new peace being an economic success for Okita and his street punks, Okita finds it boring; he misses the violence of the era before his alliance with the Yato family. He makes conflict in his personal life by being unfaithful towards Kimiyo.

However, peace is soon shattered when the Takigawa clan form an alliance with a much more powerful outside group, the Saiei group from Kobe. Takigawa is visited by a representative of the Saiei group, Owada. Yato is displeased at this: an alliance between the Takigawa clan and the Saiei group would upset the equilibrium, the balance shifting in favour of Takigawa. Yato is secretly pleased when Okita decides to begin a guerrilla war against Takigawa and the Saiei group, but this brings more violence and bloodshed to the streets of Tokyo. The last in the series of Modern Yakuza films, Fukasaku Kinji’s 1972 picture Street Mobster was a defining picture in the development of the jitsuroku (‘reality’) yakuza films of the 1970s. The film also offered a powerful role for its star, Sugawara Bunta, who had been a leading man in the 1950s but whose career took a downturn during the 1960s before gaining second wind during the early 1970s. In the 1950s and 1960s, the mukokuseki akushon (‘borderless action’) films of Nikkatsu, which began with Furukawa Takumi’s Season of the Sun in 1956, brought tales of the yakuza into the present-day. Prior to those pictures, the yakuza had usually been featured in jidaigeki pictures (period dramas). Those jidaigeki films predominantly featured Westernised villains and depicted the moral code of the yakuza in a largely positive light, as a ‘pure’ system of values that was in contrast with the more ‘corrupt’ Westernised values of the modern world. The mukokuseki akushon films, on the other hand, featured Westernised heroes in contemporary urban settings, and almost invariably offered an implicit (if not explicit) critique of the code of the yakuza which was buried in an exploration of inter-generational conflict: in those films, the elderly male leaders of yakuza clans were frequently depicted as corrupt, corporate oligarchs who victimise the more forward-thinking and youthful heroes, exploiting the protagonists’ sense of loyalty to the hierarchies of the yakuza. However, as Jasper Sharp has noted, despite their modern-day settings, the mokukuseki akushon pictures ‘bore little resemblance to any contemporary Japanese reality’ (Sharp, 2011: 182).  The mukokuseki akushon films brought yakuza stories up to date, featuring individualistic heroes who drank whisky in jazz clubs and skulked through scenes in film noir-esque chiarsoscuro lighting. The early mukokuseki akushon films were often photographed in monochrome, something which enhanced their similarities with American films noir of the 1940s and 1950s – and European films noir of the 1950s and 1960s too (including Jules Dassin’s Rififi, 1955, and Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le deuxieme souffle, 1966). Later examples of the mukokuseki akushon, however, were more frequently shot in colour, developing into mudo akushon (‘mood action’) and nyu akushon (‘new action’) films; these two forms were increasingly violent and featured protagonists who were even more morally ambiguous than their predecessors. Eventually, in the 1970s, these would be supplanted by jitsuroku pictures like Fukasaku’s Battles Without Honour and Humanity series and the same director’s Street Mobster (1971), which is usually cited as one of the first examples of jitsuroko cinema. Making use of techniques associated with cinema verite, including urgent handheld camerawork, and overlapping sound and dialogue, these jitsuroku films could be likened to the semidocumentary films noir such as Henry Hathaway’s The House on 92nd Street (1945), employing documentary-style camerawork and abrupt editing rhythms alongside storylines which more often than not were based in true accounts of life within the yakuza (or, at the very least, were claimed to be based on such accounts). The mukokuseki akushon films brought yakuza stories up to date, featuring individualistic heroes who drank whisky in jazz clubs and skulked through scenes in film noir-esque chiarsoscuro lighting. The early mukokuseki akushon films were often photographed in monochrome, something which enhanced their similarities with American films noir of the 1940s and 1950s – and European films noir of the 1950s and 1960s too (including Jules Dassin’s Rififi, 1955, and Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le deuxieme souffle, 1966). Later examples of the mukokuseki akushon, however, were more frequently shot in colour, developing into mudo akushon (‘mood action’) and nyu akushon (‘new action’) films; these two forms were increasingly violent and featured protagonists who were even more morally ambiguous than their predecessors. Eventually, in the 1970s, these would be supplanted by jitsuroku pictures like Fukasaku’s Battles Without Honour and Humanity series and the same director’s Street Mobster (1971), which is usually cited as one of the first examples of jitsuroko cinema. Making use of techniques associated with cinema verite, including urgent handheld camerawork, and overlapping sound and dialogue, these jitsuroku films could be likened to the semidocumentary films noir such as Henry Hathaway’s The House on 92nd Street (1945), employing documentary-style camerawork and abrupt editing rhythms alongside storylines which more often than not were based in true accounts of life within the yakuza (or, at the very least, were claimed to be based on such accounts).

In interview with Chris Desjardins, Fukasaku suggested that Street Mobster was a turning point in his career, a pioneering film within the jitsuroku subgenre: Street Mobster the first of his films that he ‘felt really successfully blended that documentary feel [of the jitsuroku pictures] with the fictitious drama was Street Mobster. From that film on, I was more aware of the real past and contemporary underworld, characters and events I could draw on to give the films a more reality-based feeling’ (Fukasaku, in Desjardins, 2005: 16). In fact, whilst prepping Street Mobster Fukasaku drew on the true story of yakuza Ishikawa Rikuo, on whose exploits Fukasaku’s later jitsuroku picture Graveyard of Honour (1975) would be directly based: Fukasaku commented that he was drawn to the story of Ishikawa because ‘he had come from the same area as me down in Mito […] I decided to incorporate elements of his character in Street Mobster to see how it would work. When it turned out well, I made up my mind to do the story in an even more realistic style in Graveyard of Honor’ (Fukasaku, in ibid.).  Fukasaku’s style is very much in the style of cinema verite, Fukasaku making use of overlapping dialogue, urgent handheld camerawork (which can sometimes make it difficult to decode the onscreen action), canted angles, abrupt editing, and some techniques which Fukasaku claimed were influenced by 1960s newsreels, including still frames with ticker-tape style onscreen text. ‘I believe I first came to use [handheld camerawork] on [Street Mobster]’, Fukasaku commented, ‘I myself took the camera in hand and ran into the crowds of actors and extras’ (Fukasaku, quoted in Varese, 2018: 143). The images are sometimes anchored by a voiceover from the perspective of Okita, his language feeling very spontaneous and informal. (Watching Street Mobster in particular, out of all of Fukasaku’s jitsuroku films, one might marvel at the synchronicity between Fukasaku’s technique and Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets, 1973.) However, in other sequences Fukasaku’s technique is more expressionistic and symbolic: in a number of scenes, the sets are bathed in dark shadows, the actors lit in a chiaroscuro fashion, sometimes by Mario Bava-esque primary coloured lights. Whilst Street Mobster displays a good handful of the ‘reality’ techniques of the jitsuroku pictures, it doesn’t represent a complete break with the more expressionistic, noir-esque style of the mudo akushon (‘mood action’) films of the late 1960s. However, without doubt it’s an important stepping stone to the naturalism of Fukasaku’s Battles Without Honour and Humanity series. As in any number of Japanese films of this period, there are also some visual allusions to Japanese experimental photography of the kind found in the pages of the short-lived but groundbreaking experimental Japanese photography magazine Purovōku: shisō no tame no chōhatsuteki shiryō/Provoke: Provocative Documents for the Sake of Social Thought (1968-70). These sophisticated techniques are offset by the film’s frequently deeply earthy content. Fukasaku’s style is very much in the style of cinema verite, Fukasaku making use of overlapping dialogue, urgent handheld camerawork (which can sometimes make it difficult to decode the onscreen action), canted angles, abrupt editing, and some techniques which Fukasaku claimed were influenced by 1960s newsreels, including still frames with ticker-tape style onscreen text. ‘I believe I first came to use [handheld camerawork] on [Street Mobster]’, Fukasaku commented, ‘I myself took the camera in hand and ran into the crowds of actors and extras’ (Fukasaku, quoted in Varese, 2018: 143). The images are sometimes anchored by a voiceover from the perspective of Okita, his language feeling very spontaneous and informal. (Watching Street Mobster in particular, out of all of Fukasaku’s jitsuroku films, one might marvel at the synchronicity between Fukasaku’s technique and Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets, 1973.) However, in other sequences Fukasaku’s technique is more expressionistic and symbolic: in a number of scenes, the sets are bathed in dark shadows, the actors lit in a chiaroscuro fashion, sometimes by Mario Bava-esque primary coloured lights. Whilst Street Mobster displays a good handful of the ‘reality’ techniques of the jitsuroku pictures, it doesn’t represent a complete break with the more expressionistic, noir-esque style of the mudo akushon (‘mood action’) films of the late 1960s. However, without doubt it’s an important stepping stone to the naturalism of Fukasaku’s Battles Without Honour and Humanity series. As in any number of Japanese films of this period, there are also some visual allusions to Japanese experimental photography of the kind found in the pages of the short-lived but groundbreaking experimental Japanese photography magazine Purovōku: shisō no tame no chōhatsuteki shiryō/Provoke: Provocative Documents for the Sake of Social Thought (1968-70). These sophisticated techniques are offset by the film’s frequently deeply earthy content.

The film’s claims to realism are amplified by the presence in the cast of real life former yakuza Ando Noboru, who plays Yato; in 1964, Ando had reinvented himself as an actor after serving six years in prison for commissioning the murder of a businessman, Yokoi Hideki, who owed a debt to Ando’s group. (Ando’s story was told in a number of films, including Sato Junya’s early jitsuroku trilogy – 1972’s Yakuza and Feuds and The Untold Story of the Ando Gang: The Killer Brother, and 1973’s The True Account of the Ando Gang: Attack – which were based on Ando’s autobiography Yakuza and Feuds and featured Ando himself in the lead role.)  Street Mobster is notable for containing one of the more rounded female characters in a jitsuroku picture, a subgenre not known for its strong female roles. Within the film’s narrative, Kimiyo is essential in challenging Okita and making him face up to his past transgressions, whilst forging a new path into the future. As Chris Desjardins notes in his interview with Fukasaku, prior to going to prison Okita’s only sexual experiences with women seem to be through rape, until after his release from prison he begins a relationship with the prostitute Kimiyo – who, during Okita’s prior criminal career, he ‘turned out’ by gang-raping her upon her arrival in Tokyo. Responding to Chris Desjardin’s questions as to why there are so few strong, rounded female roles in the jitsuroku pictures (ironically, Street Mobster is arguably an exception, in terms of Kimiyo’s role in the narrative), Fukasaku suggested that ‘when you do a jitsuroku yakuza film, just by its nature you’re going to be telling a tale about men. And when you have to concentrate on one or two male characters, you just don’t have the space to concentrate as much on any female roles’ (Fukasaku, in Desjardins, op cit.: 19). Street Mobster is notable for containing one of the more rounded female characters in a jitsuroku picture, a subgenre not known for its strong female roles. Within the film’s narrative, Kimiyo is essential in challenging Okita and making him face up to his past transgressions, whilst forging a new path into the future. As Chris Desjardins notes in his interview with Fukasaku, prior to going to prison Okita’s only sexual experiences with women seem to be through rape, until after his release from prison he begins a relationship with the prostitute Kimiyo – who, during Okita’s prior criminal career, he ‘turned out’ by gang-raping her upon her arrival in Tokyo. Responding to Chris Desjardin’s questions as to why there are so few strong, rounded female roles in the jitsuroku pictures (ironically, Street Mobster is arguably an exception, in terms of Kimiyo’s role in the narrative), Fukasaku suggested that ‘when you do a jitsuroku yakuza film, just by its nature you’re going to be telling a tale about men. And when you have to concentrate on one or two male characters, you just don’t have the space to concentrate as much on any female roles’ (Fukasaku, in Desjardins, op cit.: 19).

Okita is a combative protagonist, and the film is arguably picaresque. Okita introduces the film with a voiceover declaring ‘I like fights and girls, but I’m not good at gambling’. Born on the 15th of August 1945, Okita notes in his narration that his day of birth was ‘The day Japan lost the war. So I share the same fate’. He reveals very quickly that he is the illegitimate son of a prostitute who treated him cruelly, and to whom he reacted with violence: ‘I beat up many guys in my life’, Okita asserts, ‘My mom too. The memory makes me sick’. When Okita is released from prison, he’s shocked by how much the world has changed: ‘Streets were filled with gangsters before but now with straight people’, he narrates, ‘Young guys too, they had long hair like chicks’. Okita is fiercely independent, telling the young punks he takes under his wing that ‘He [Takigawa] made use of you while you made money for him. Don’t depend on gangsters. Get what you want with your own hands’. Later, when Yato tries to persuade Okita to join the Yato family, Okita initially resists, asserting that ‘I don’t belong in anyone’s gang. Never have done, never will’. Okita eventually accepts the alliance with the Yato family, but the film features an ellipsis before Okita is shown onscreen, accompanied by voiceover narration in which he asserts that ‘I just wasn’t enjoying it [the new peace between the clans]. I had no opportunities for fighting [….] All I could do was make love’. Later, he adds, also in voiceover, ‘As I look back at those times, they’d already begun to destroy us’. At this point, Okita seems to be reflecting on his relationship with Kimiyo and his infidelity towards her, but his comments also reflect his attitude towards the era of peace between the clans. Ultimately, Street Mobster is a relentless depiction of an equally relentless protagonist, who would rather fight than fuck.

Video

Taking up 22 Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc, Street Mobster is presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec. The film is uncut, with a running time of 87:45. The film’s original aspect ratio of 2.35:1 is employed. As noted above, the film makes use of some experimental techniques, including freeze frames and onscreen titles. A sense of cinema verite is communicated through the relentless handheld camerawork too. It’s a coarse film with an aggressive style, and this is communicated nicely on this Blu-ray release. Detail is good and damage is minimal. The image is sometimes slightly soft and diffused, but this could be a product of the zoom lenses that are employed at numerous times throughout the film. It’s unclear what the source for this presentation was, but it seems a fairly safe assumption that it’s a master provided by the film’s rights holders. Contrast levels are mostly pleasing but there’s some ‘crush’ in the shadow detail: whilst midtones are rich and defined, the curve drops steeply into the toe. (It’s worth noting that the source may very well be a positive source of some kind.) The structure of 35mm film is present and the encode to disc is functional. Colours are consistent, and the scenes which feature primary coloured gels on the lights and blinking neon signs are impressively handled. Taking up 22 Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc, Street Mobster is presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec. The film is uncut, with a running time of 87:45. The film’s original aspect ratio of 2.35:1 is employed. As noted above, the film makes use of some experimental techniques, including freeze frames and onscreen titles. A sense of cinema verite is communicated through the relentless handheld camerawork too. It’s a coarse film with an aggressive style, and this is communicated nicely on this Blu-ray release. Detail is good and damage is minimal. The image is sometimes slightly soft and diffused, but this could be a product of the zoom lenses that are employed at numerous times throughout the film. It’s unclear what the source for this presentation was, but it seems a fairly safe assumption that it’s a master provided by the film’s rights holders. Contrast levels are mostly pleasing but there’s some ‘crush’ in the shadow detail: whilst midtones are rich and defined, the curve drops steeply into the toe. (It’s worth noting that the source may very well be a positive source of some kind.) The structure of 35mm film is present and the encode to disc is functional. Colours are consistent, and the scenes which feature primary coloured gels on the lights and blinking neon signs are impressively handled.

Some full-sized screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

Audio is presented, in Japanese, via a LPCM 2.0 mono track. This is rich and deep with no noticeable distortion. Optional English subtitles are provided. These are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes: - An audio commentary with Tom Mes. Mes talks about Street Mobster’s place in the development of the jitsuroku. He discusses the origins of the film and discusses the relationship between these films and the post-war yakuza. Mes reflects on Fukasaku’s urgent style of filmmaking in his jitsuroku films and situates Street Mobster within the careers of Fukasaku and the picture’s cast. - Trailer (2:41). - Stills Gallery (1:00).

Overall

Sometimes dismissed as a ‘practice run’ for Fukasaku’s later, more celebrated picture Graveyard of Honour, Street Mobster is nonetheless an impactful film, especially when watched in isolation from the jitsuroku pictures that followed. A turning point in its director’s filmography (and arguably in terms of the yakuza picture more generally), Street Mobster is also notable for Nagisa Mayumi’s bold performance as Mikomi, arguably one of the most rounded female roles in the jitsuroku subgenre as a whole. The relentless Okita is also an excellent part for Sugawara, Okita’s nihilism being captured in his love of violence and his realisation that, as he tells Kizaki, ‘We’ll die on the street in the end’. For Okita, violence is essential: ‘An underdog forgets how to bite its enemy’, he tells Kizaki, ‘Once you learn how to run, you can never fight back’. Sometimes dismissed as a ‘practice run’ for Fukasaku’s later, more celebrated picture Graveyard of Honour, Street Mobster is nonetheless an impactful film, especially when watched in isolation from the jitsuroku pictures that followed. A turning point in its director’s filmography (and arguably in terms of the yakuza picture more generally), Street Mobster is also notable for Nagisa Mayumi’s bold performance as Mikomi, arguably one of the most rounded female roles in the jitsuroku subgenre as a whole. The relentless Okita is also an excellent part for Sugawara, Okita’s nihilism being captured in his love of violence and his realisation that, as he tells Kizaki, ‘We’ll die on the street in the end’. For Okita, violence is essential: ‘An underdog forgets how to bite its enemy’, he tells Kizaki, ‘Once you learn how to run, you can never fight back’.

Arrow’s new Blu-ray presentation of Street Mobster is very good and is supported by a strong commentary from Tom Mes. Fans of jitsuroku pictures and/or of the work of Fukasaku will find this to be an essential purchase. References: Desjardins, Chris, 2005: Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film. London: I B Tauris Jacoby, Alexander, 2008: A Critical Handbook of Japanese Film Directors: From the Silent Era to the Present Day. California: Stonebridge Press Sharp, Jasper, 2011: Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema. Maryland: Scarecrow Press Taylor-Jones, Kate E (2013): Rising Sun, Divided Land: Japanese and South Korean Filmmakers. London: Wallflower Press Varese, Federico, 2018: Mafia Life: Love, Death and Money at the Heart of Organized Crime. Oxford University Press Please click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|