|

|

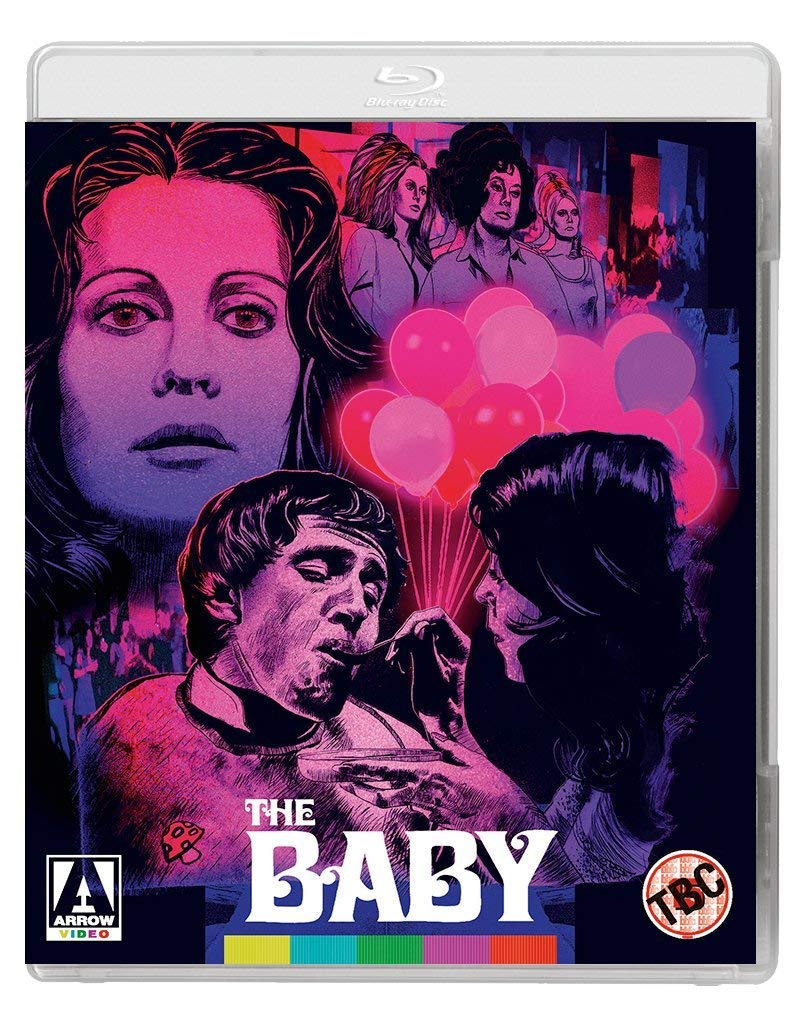

Baby (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (7th October 2018). |

|

The Film

The Baby (Ted Post, 1973) The Baby (Ted Post, 1973)

Social worker Ann Gentry (Anjanette Comer) is assigned to the Wadsworth family, headed by its matriarch, Mrs Wadsworth (Ruth Roman), and consisting of her daughter Germaine (Marianna Hill) and Alba (Susanne Zenor). Ann’s job is to oversee the Wadsworths’ care of Baby (David Mooney), Mrs Wadsworth’s 21 year old son, who is unable to walk or talk and lives as an oversized baby – to the extent that he sleeps in a cot and wears nappies. Ann is clearly fascinated by Baby and takes a deep interest in him, which leads to friction between Ann and her boss Mr Foley (Joseph Bernard). Ann’s interest in Baby also leads to conflict between Ann and the Wadsworths; at one point, they suggest that Ann go with them on a hike in the mountains. However, realising that the social workers who have been assigned assigned to the Wadsworths previously have all disappeared, Ann suspects that the Wadsworths mean to do her harm and refuses. Believing that the Wadsworths are using forms of punishment to prevent Baby from developing normally, Ann also reaches the conclusion that Mrs Wadsworth has prevented Baby’s development as a form of revenge against the male gender. The Wadsworths invite Ann to Baby’s birthday party but spike Ann’s drink, holding her captive in the basement. However, with the help of Baby, Ann manages to escape. She and Baby flee the Wadsworth house, pursued by Mrs Wadsworth, Alba and Germaine.  A bizarre film that has developed a strong cult following in the years since its original release, Ted Post’s The Baby (1973) is, legend has it, based on a true story. Post deliberately opted to shoot the picture in a very ‘flat’, almost television production-like manner in order to avoid placing emphasis on the more lurid aspects of the script (for example, Germaine’s sexual exploitation of her infant-like brother) (see Kelley, 2003: 50). Critic Mike Kelley has suggested that ‘the main reason […] The Baby is so disturbing is because it is a drama’ and Post underplays the material, which in other hands might have been presented in an almost hysterical manner (ibid.: 53). The result is a picture that possesses a ‘repressive, almost puritanical, style’ which ‘directs our full attention to the film’s storyline’ (ibid.). This made the film difficult to market, and as Kelley notes, the advertising materials produced to accompany the film’s release ‘portray[ed] the film as either horror or soft-core porn’ (ibid.). A bizarre film that has developed a strong cult following in the years since its original release, Ted Post’s The Baby (1973) is, legend has it, based on a true story. Post deliberately opted to shoot the picture in a very ‘flat’, almost television production-like manner in order to avoid placing emphasis on the more lurid aspects of the script (for example, Germaine’s sexual exploitation of her infant-like brother) (see Kelley, 2003: 50). Critic Mike Kelley has suggested that ‘the main reason […] The Baby is so disturbing is because it is a drama’ and Post underplays the material, which in other hands might have been presented in an almost hysterical manner (ibid.: 53). The result is a picture that possesses a ‘repressive, almost puritanical, style’ which ‘directs our full attention to the film’s storyline’ (ibid.). This made the film difficult to market, and as Kelley notes, the advertising materials produced to accompany the film’s release ‘portray[ed] the film as either horror or soft-core porn’ (ibid.).

For much of the film’s running time, the audience is left to wonder whether Baby’s ‘condition’ is innate or if it has been learned and reinforced by his family. Where Ann is convinced that Baby is ‘capable of growth and development’, Mrs Wadsworth insists simply that ‘Baby was born backwards. He’s been that way all his life, and that’s all there is to it’. Interestingly, however obliquely, the film shares a similar focus on the nature/nurture debate (and issues of educational psychology – such as the merits or otherwise of unstructured play) as Alan Cooke’s The Mind of Mr Soames (1969), which has recently been released on Blu-ray by Powerhouse Films. In Cooke’s film, Terence Stamp plays John Soames, a 30 year old man who has been in a coma since birth and is awakened after experimental brain surgery; Soames finds himself in a new world, an infant in a child’s body, as two scientists (Nigel Davenport and Robert Vaughn) come into conflict over their approaches to his development. The parallels with The Baby are obvious, and comparisons may be drawn between Stamp’s performance as the infant-like Soames and David Mooney’s role as Baby in Ted Post’s picture. However, Post’s film ups the ante in terms of using, quite bizarrely, dubbing Mooney with the cries and coos of a seemingly very real ‘baby’.  Mrs Wadsworth’s reasons for crippling the development of her son are rendered slightly ambiguously – though towards its final sequences, Ann offers a psychological explanation which seems to strike a nerve with Mrs Wadsworth herself. Certainly, Baby is a meal ticket for the Wadsworths, who as Mrs Wadsworth admits to Ann in an early scene in the picture, live off the money ‘the county gives us for Baby’. Meanwhile, there’s a strange and disturbing undercurrent of sexual perversity which is thrust to the foreground of the action in a sequence in which a babysitter is left to care for Baby and changes his nappy; he paws at her breast and she allows him to suckle at her nipple. At that moment, the Wadsworths return home and Mrs Wadsworth flies into a fit of rage, screaming in response to the babysitter’s assertion that ‘nothing happened’: ‘Putting your damn tit in his mouth and you call that nothing? [….] He’s a baby, and you had to put your hands on him!’ Mrs Wadsworth assaults the babysitter, who leaves. However, not long afterwards is an even more disturbing scene in which Germaine strips naked before climbing into Baby’s cot, the film quite openly suggesting that Germaine has been sexually abusing her brother for some time. Mrs Wadsworth’s reasons for crippling the development of her son are rendered slightly ambiguously – though towards its final sequences, Ann offers a psychological explanation which seems to strike a nerve with Mrs Wadsworth herself. Certainly, Baby is a meal ticket for the Wadsworths, who as Mrs Wadsworth admits to Ann in an early scene in the picture, live off the money ‘the county gives us for Baby’. Meanwhile, there’s a strange and disturbing undercurrent of sexual perversity which is thrust to the foreground of the action in a sequence in which a babysitter is left to care for Baby and changes his nappy; he paws at her breast and she allows him to suckle at her nipple. At that moment, the Wadsworths return home and Mrs Wadsworth flies into a fit of rage, screaming in response to the babysitter’s assertion that ‘nothing happened’: ‘Putting your damn tit in his mouth and you call that nothing? [….] He’s a baby, and you had to put your hands on him!’ Mrs Wadsworth assaults the babysitter, who leaves. However, not long afterwards is an even more disturbing scene in which Germaine strips naked before climbing into Baby’s cot, the film quite openly suggesting that Germaine has been sexually abusing her brother for some time.

Nevertheless, despite the film’s all-too-clear framing of the Wadsworths as the villains of its narrative, the ‘rescue’ of Baby is complicated by the motives of Ann, who does not wish to remedy Baby’s retardation but instead intends to keep Baby as a ‘baby’, using him as a playmate for her husband. The film is also complicated by issues of audience identification: for much of the film’s running time, the audience is led to identify with Ann, the film reversing the typical gender stereotypes associated with popular cinema. (To apply some of narratologist Vladimir Propp’s supposedly archetypal character types to the story, Ann is the film’s Hero, Baby is the Princess, and Mrs Wadsworth is the Princess’ Father.) However, this is challenged by the revelations that take place in the final sequences of the picture.  Made in the era of Women’s Lib, it’s difficult not to see The Baby as a backlash against the ideology of that movement. The Wadsworth household is a deeply corrupt matriarchy which is financed through the exploitation of Baby; early in the film, Mrs Wadsworth concedes that the family’s only source of income is the money given to the women by the county for the care of Baby. Baby is a young man who is oppressed and abused by the women in his life – including his own mother, who displays an undercurrent of hostility towards the male gender that manifests itself more directly in the behaviour of her daughters Germaine and Alba – one of whom tortures Baby with an electric cattle prod, and the other of whom exploits Baby sexually by climbing into his crib at night. (Though depicted obliquely, the latter incident is one of the most disturbing in the film, especially considering its ‘PG’ rating in the US.) When Mrs Wadsworth tells Ann that her husband left her, it is with a tinge of delight rather than regret: ‘Like all things, some good came out of it’, Mrs Wadsworth says, ‘We got used to being without a man’. Later, Ann asserts that she believes Mrs Wadsworth is ‘taking revenge on the only male member of the family’ in reaction to the fact that she has been abandoned by all three of her children’s fathers. It’s tempting to see the Wadsworth family as a metonymic depiction of a society in which gender roles were undergoing significant changes, with Baby representing a generation of young men who, in some quarters, may have been perceived as being seen as redundant or even subject to exploitation and abuse. As Ann tells the headteacher of a school for ‘gifted’ children, ‘Can you think of anything more horrible than being buried alive? Well, that’s what happened to this client. He’s been imprisoned by a kind of sick love. There’s a normal full-grown man, trapped, with no way out’. Made in the era of Women’s Lib, it’s difficult not to see The Baby as a backlash against the ideology of that movement. The Wadsworth household is a deeply corrupt matriarchy which is financed through the exploitation of Baby; early in the film, Mrs Wadsworth concedes that the family’s only source of income is the money given to the women by the county for the care of Baby. Baby is a young man who is oppressed and abused by the women in his life – including his own mother, who displays an undercurrent of hostility towards the male gender that manifests itself more directly in the behaviour of her daughters Germaine and Alba – one of whom tortures Baby with an electric cattle prod, and the other of whom exploits Baby sexually by climbing into his crib at night. (Though depicted obliquely, the latter incident is one of the most disturbing in the film, especially considering its ‘PG’ rating in the US.) When Mrs Wadsworth tells Ann that her husband left her, it is with a tinge of delight rather than regret: ‘Like all things, some good came out of it’, Mrs Wadsworth says, ‘We got used to being without a man’. Later, Ann asserts that she believes Mrs Wadsworth is ‘taking revenge on the only male member of the family’ in reaction to the fact that she has been abandoned by all three of her children’s fathers. It’s tempting to see the Wadsworth family as a metonymic depiction of a society in which gender roles were undergoing significant changes, with Baby representing a generation of young men who, in some quarters, may have been perceived as being seen as redundant or even subject to exploitation and abuse. As Ann tells the headteacher of a school for ‘gifted’ children, ‘Can you think of anything more horrible than being buried alive? Well, that’s what happened to this client. He’s been imprisoned by a kind of sick love. There’s a normal full-grown man, trapped, with no way out’.

Video

Presented uncut, with a running time of 85:00, Arrow’s Blu-ray release of The Baby contains two versions of the film: the first in the 1.78:1 ratio (filling just under 19Gb of space on the disc), and a second presentation in the 1.37:1 ratio (taking up a little under 17Gb of space on the disc). The former is closer to the aspect ratio of the film’s release to cinemas (which would have been 1.85:1). Compositions seem fine at 1.78:1, whilst the open-matte 1.37:1 presentation may be more familiar to those who first saw the film via television screenings or on VHS (and also reinforces the intentionally television movie-like aesthetic of the picture, discussed above). The 1.78:1 presentation obviously loses some visual information at top and bottom of the frame but also includes a little more visual information at the left and right hand edges of the frame. A direct visual comparison of the two presentations can be found at the bottom of this review, via full-sized screengrabs. (Please click these to enlarge them.) Presented uncut, with a running time of 85:00, Arrow’s Blu-ray release of The Baby contains two versions of the film: the first in the 1.78:1 ratio (filling just under 19Gb of space on the disc), and a second presentation in the 1.37:1 ratio (taking up a little under 17Gb of space on the disc). The former is closer to the aspect ratio of the film’s release to cinemas (which would have been 1.85:1). Compositions seem fine at 1.78:1, whilst the open-matte 1.37:1 presentation may be more familiar to those who first saw the film via television screenings or on VHS (and also reinforces the intentionally television movie-like aesthetic of the picture, discussed above). The 1.78:1 presentation obviously loses some visual information at top and bottom of the frame but also includes a little more visual information at the left and right hand edges of the frame. A direct visual comparison of the two presentations can be found at the bottom of this review, via full-sized screengrabs. (Please click these to enlarge them.)

The film was shot on 35mm colour stock. Colours are naturalistic, and damage is limited to some very minor blemishes in the emulsions. Detail is very good, with some impressive dine detail being conveyed in close-ups. Contrast is for the most part strong, with both high contrast scenes and low-light scenes faring well and defined midtones being balanced by gradation into the shadows. However, there’s a single scene, about an hour into the picture, with the camera place inside a house in which the exterior view (through a window) is blown out very severely – in a manner that seems to reflect the compressed dynamic range of digital video rather than the more expansive dynamic range of celluloid. (See the large screengrabs at the bottom of this review.) Finally, a solid encode to disc ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 track, which is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. The audio track is for the most part fine, and dialogue is audible throughout, though there is some very subtle distortion to this track in some places. Subtitles are easy to read and accurate.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with Travis Crawford. Crawford begins by calling the picture ‘one of the strangest and most perverse American horror films of the 1970s’. He situates the film within its era of production, reflecting on its relationship with some of the other US horror films of the 1970s. He talks at length about the personnel involved in the production and examines some of its themes. It’s a well-researched and engaging commentary track. - ‘A Family Affair’ (5:43). This new interview with actress Marianna Hill focuses on her work on The Baby. Hill discusses Post’s approach as a director, and she talks about how she essayed the role of Germaine. - ‘Nursery Crimes’ (6:27). In another new interview, Stanley Dyrector, who created the paintings seen in the nursery in the picture, discusses his work on the film (which he says made it ‘freakin’ real’). He also says that he acted in the film, though his scenes were deleted from the finished edit. - ‘Down Will Come Baby’ (12:01). In an interview ported over from Severin’s US release of the picture, Rebekah McKendry, a maker of short films herself and a lecturer in USC’s Cinematic Arts faculty, reflects on her first viewing of The Baby and talks about its place in Ted Post’s filmmaking career, discussing some of its themes. The interview with McKendry is framed with a bizarre red vignette, added in postproduction, which is quite hard on the eyes; but the content of the interview is solid and engaging. - ‘Tales from the Crib’ (20:00). This is an audio interview with Ted Post, apparently conducted via telephone, in which the director talks about how he came to be involved in making the film and discusses his approach to the material. - ‘Baby Talk’ (14:41). This is another audio interview, this time with actor David Mooney; Mooney discusses his role in the picture and his relationships with both Post and the other cast members. - Original Trailer (2:45).

Overall

The Baby is a strange, unforgettable picture that is filled with off-kilter moments – both intentional and unintentional. (Amongst the latter is a scene in which Alba gives Baby a toy lion but claims in the dialogue that it is a tiger.) The ‘flat’ TV movie-like aesthetic of the picture was, it seems, intentional – and works in the film’s favour, so that the more outrageous moments within the narrative have far greater impact. The Baby is a strange, unforgettable picture that is filled with off-kilter moments – both intentional and unintentional. (Amongst the latter is a scene in which Alba gives Baby a toy lion but claims in the dialogue that it is a tiger.) The ‘flat’ TV movie-like aesthetic of the picture was, it seems, intentional – and works in the film’s favour, so that the more outrageous moments within the narrative have far greater impact.

Arrow’s new Blu-ray release contains a pleasing presentation of the main feature. (Though there is one scene, as noted above, which displays oddly video-like contrast and flattened dynamic range.) The 1.33:1 presentation is arguably redundant though seems to have been included for the sake of nostalgia. Beyond the main presentation, the disc contains a pretty solid array of contextual material, the most interesting of which are the interviews with Ted Post and Dyrector. References: Kelley, Mike, 2003: Foul Perfection: Essays and Criticism. Massachusetts Institute of Technology Visual comparison of 1.78:1 and 1.33:1 presentations. (Please click to enlarge.)

|

|||||

|