|

|

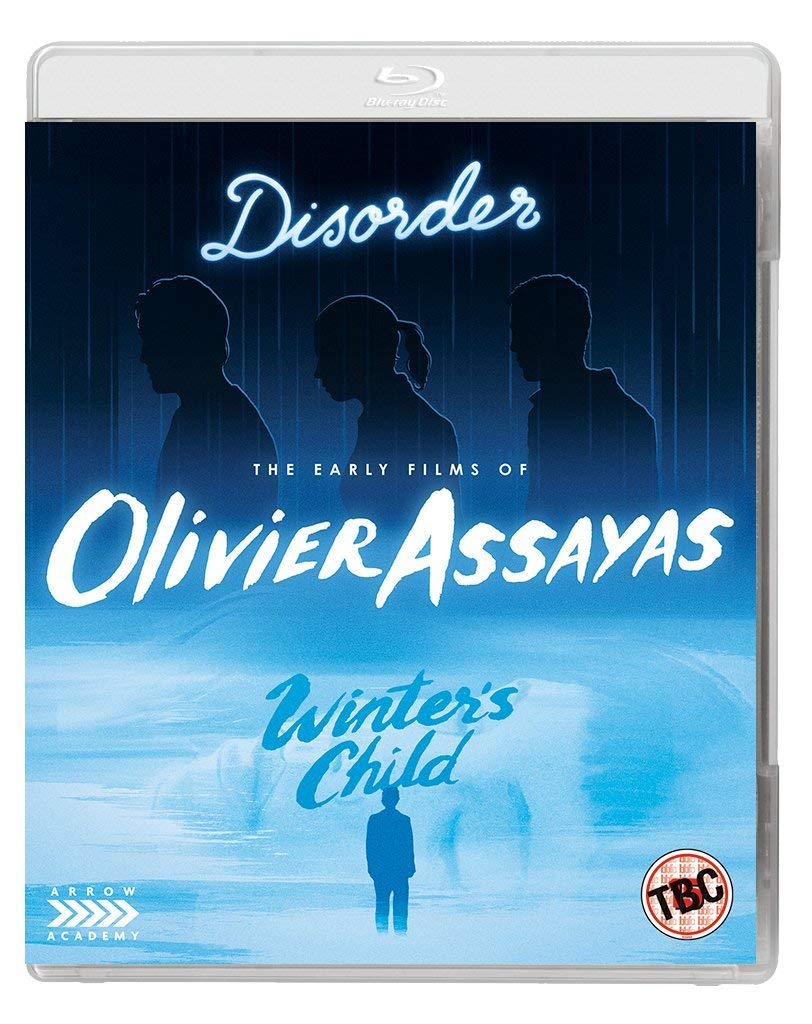

Disorder AKA Désordre (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (26th October 2018). |

|

The Film

The Early Films of Olivier Assayas  Désordre (Disorder, 1986) Désordre (Disorder, 1986)

Henri (Lucas Belvaux), Yvan (Wadeck Stanzack) and Anne (Ann-Gisel Glass) break into a music shop with the intention of stealing instruments that can be used in an upcoming performance by their band. However, they are interrupted by the shop’s owner, who holds Henri at gunpoint. The shop’s owner is surprised by Yvan, who uses a guitar string as a makeshift garrotte and throttles the shopkeeper, killing him. The remorseless Yvan makes Henri and Anne take a vow of silence, though Henri suggests that they should go to the police. The trio return to the warehouse which their band have made their rehearsal space, where they interrupt the group’s ‘roadie’ Marc (Philippe Demarle), who is in flagrante with Cecile (Juliette Mailhe), the girlfriend of another member of the band, Xavier (Remi Martin). When Xavier and Gabriel (Simon de la Brosse) return, they chastise Yvan for failing to return with the new instruments they need for their upcoming gig. Meanwhile, it is revealed that Anne, who is involved romantically with Henri, is conducting a passionate affair with Yvan. The group’s manager Albertini (Etienne Chicot) tells the band that CBS is interested in recording an album with them, but the group will have to rethink Xavier’s role: Xavier is due to begin his military service and cannot commit to the recording schedule. On the eve of Xavier’s departure, he sees Marc kissing Cecile at a gig; Xavier confronts the pair. In the morning, a distressed Xavier causes the car he is driving to crash, injuring himself, Anne and Yvan – who are traveling in the vehicle as passengers. During a heated exchange, Xavier reveals that he knows about the murder of the shopkeeper; he leaves the group and heads towards his barracks.  With Xavier gone, the remaining members of the group travel to London for their meeting with executives of CBS. On the journey, Yvan begins a passionate relationship with Cora (Corinne Dacia), a photographer who is there to document the band’s activities. However, Anne sees Yvan and Cora in an embrace; she confronts Yvan, who abandons the journey to London, choosing instead to hide out in Newhaven with Cora. Yvan intends to abandon the band and return to Paris. Shortly afterwards, Gabriel reveals to Henri that he too wishes to leave the band: ‘It was fun. It’s no longer fun’, Gabriel says. With Xavier gone, the remaining members of the group travel to London for their meeting with executives of CBS. On the journey, Yvan begins a passionate relationship with Cora (Corinne Dacia), a photographer who is there to document the band’s activities. However, Anne sees Yvan and Cora in an embrace; she confronts Yvan, who abandons the journey to London, choosing instead to hide out in Newhaven with Cora. Yvan intends to abandon the band and return to Paris. Shortly afterwards, Gabriel reveals to Henri that he too wishes to leave the band: ‘It was fun. It’s no longer fun’, Gabriel says.

A year later, Yvan is still involved with Cora, but this relationship soon comes to an end when Cora confronts Yvan about the fact that during the months since the band broke up, he’s been unable to write any music and has in living off Cora’s earnings. In response, Yvan explodes and attacks Cora. He then seeks out Henri, who offers the now homeless Yvan a room. However, Henri returns home to find Yvan dead: Yvan has hanged himself. At Yvan’s funeral, Henri meets Gabriel, who is now working in his father’s garage and married to a woman named Sylvie. Gabriel asserts he believed that out of all of the members of the band, he expected Yvan to succeed. Henri also reconnects with Anne, who is involved in a relationship with a ‘sugar daddy’, Paul. Albertini has another proposition for Henri, however: Marc, the band’s former ‘roadie’, is now an accomplished musician and is due to record an album in New York. Marc has asked that Henri be employed as a session musician on the album, and Marc and Henri travel to America together. However, against Marc’s wishes Henri is quietly replaced by the record company…  L’enfant de l’hiver (Winter’s Child, 1989) L’enfant de l’hiver (Winter’s Child, 1989)

Heavily pregnant Natalia (Marie Matheron) awakes, believing that she has gone into labour. She calls out for her lover Stephane (Michel Feller) but he is nowhere to be found. In the morning, Stephane returns and treats Natalia coldly, telling her he doesn’t want ‘it [the baby] or you’. Stephane leaves Natalia and returns to his other lover, theatrical set designer Sabine (Clotilde de Bayser). Stephane drives out to his father’s house with Sabine. However, Stephane’s father, whom Stephane believes to be in China, is there. Stephane’s father tells him that he plans to sell his antiques shop so that he may spend his assets: he does not plan to pass anything on to his listless offspring. During their conversation, Sabine departs, returning to her lover Bruno (Jean-Phillippe Ecoffey). Bruno is an actor in the same theatre company for which Sabine works. Bruno is also married, to Maryse (Virginie Thevenet). Bruno and Sabine had a fling together, whilst their theatre company was in South America, but on returning to France Bruno decided to end their relationship. However, Sabine has other ideas, threatening Bruno with a knife and injuring him. Following this, Sabine is warned by the director of the theatre company to stay away from Bruno. Meanwhile, Natalia is found collapsed, having attempted suicide. She pulls through and is hospitalised. Stephane makes an attempt to visit her but is turned away. He returns instead to Sabine. Months later, Stephane and Sabine visit the Italian countryside with Stephane’s friend Jean-Marie (Vincent Vallier) and his lover Leni (Nathalie Richard). Sabine reveals that she was once pregnant but had an abortion, and she wonders how Stephane could abandon a woman who was pregnant with his child. Jean-Marie reveals that Natalia has found solace in promiscuity and has a cold relationship with her child.  When Stephane’s father suffers a stroke and passes away, Stephane leaves Italy and returns to Paris. Stephane’s sister, Agnes, is there also. At the same time, Sabine returns to Paris and begins to stalk Bruno. When Stephane’s father suffers a stroke and passes away, Stephane leaves Italy and returns to Paris. Stephane’s sister, Agnes, is there also. At the same time, Sabine returns to Paris and begins to stalk Bruno.

Stephane gets in touch with Natalia, who is working as a teacher in a night school. Natalia reveals that she is now living with a man named Richard, who has adopted the child and is raising it as if it were his own. Stephane suggests he would like to act as a parent to the baby, but Natalia refuses, reminding him of how he abandoned the pregnant Natalia. Stephane breaks into Natalia’s home at night and spends time with the child, who he discovers is a baby boy. Time passes, and Stephane and Natalia meet up at a party. Though Natalia is still involved with Richard, Stephane insists on declaring his affection for her and makes a clumsy attempt to seduce her. Natalia, sensibly, rebuffs his advances, though with the passage of time a form of reconciliation seems possible. A critic turned (prolific) filmmaker, Olivier Assayas’ first film to achieve major international distribution was Irma Vep in 1996. With that picture, Assayas achieved an internationalisation of form and content: Irma Vep was a postmodern film about a remake of Feuillade’s silent serial Les vampires which featured Hong Kong actress Maggie Cheung (playing herself), and included references to Cheung-starring Hong Kong pictures such as Johnnie To’s The Heroic Trio (1993). This has been followed through with Assayas’ subsequent films – which are increasingly international in terms of production circumstances, casting and narrative content: his 2007 film Boarding Gate featured a highly international cast (Asia Argento, Michael Madsen, Carl Ng, Kelly Lin, Sondra Locke) and was shot in Paris and Hong Kong, whilst his 2010 television mini-series Carlos the Jackal starred Edgar Ramirez as Ilich Ramirez Sanchez, the Venezuelan Marxist revolutionary/terrorist, and a narrative which could be described legitimately as ‘globetrotting’.  These two early films by Assayas, however, are predominantly localised within Paris though there are sojourns within the narratives to other places (London and New York in Disorder; rural Italy in Winter’s Child). In his book Born in Flames (2007). Howard Hampton has described Assayas’ feature film debut Disorder as ‘a doomed but somewhat engaging marriage of Dostoyevsky and the postpunk scene’ (Hampton, 2007: 89). The film depicts a band who suffer the fallout of Yvan’s murder of a shopkeeper during a break-in, a narrative which Hampton summarises as ‘Crime and Joy Division’ (ibid.). These two early films by Assayas, however, are predominantly localised within Paris though there are sojourns within the narratives to other places (London and New York in Disorder; rural Italy in Winter’s Child). In his book Born in Flames (2007). Howard Hampton has described Assayas’ feature film debut Disorder as ‘a doomed but somewhat engaging marriage of Dostoyevsky and the postpunk scene’ (Hampton, 2007: 89). The film depicts a band who suffer the fallout of Yvan’s murder of a shopkeeper during a break-in, a narrative which Hampton summarises as ‘Crime and Joy Division’ (ibid.).

As the narrative of Disorder progresses, the group of young people depicted at its core – the menage-a-trois of Henri, Yvan and Anne, their associate Gabriel and the second menage-a-trois of Marc, Xavier and Cecile – find their relationships fragmenting as they are pulled (or begin to grow) apart. The promise of their burgeoning musical careers is cut short by the realities of relationships and the difficulties they face in ‘getting along’ with one another. By the end of the story, the tables have turned and the loner/outsider to the group, Marc, has found a modicum of success in music whilst the others have gone on to live mundane lives within the petit bourgeoisie. (This is in contradiction to what the members of the group expected: Xavier in particular asserts, following Yvan’s death by suicide, that he always expected Yvan to succeed in his ambitions.) As Kent Jones says, at the end of the picture ‘Everyone ends in either confusion, capitulation, or suicide, and along the way betrayal is the only constant’ (Jones, 2007: 6).  For most of the running time of Disorder, the audience’s perspective on the action is guided by Henri, who is held at gunpoint by the shopkeeper in the break-in that opens the film, and who acts as the moral conscience of the group after Yvan kills the same shopkeeper. Relationships are initially soured by Yvan’s demand that Anne and Henri vow not to reveal what happened in the shop that night, reinforced by Yvan’s attempts to deflect blame for the shopkeeper’s death onto his friends. (‘You made me’, Yvan tells Henri angrily when Henri asserts, ‘We’ve killed him [the shopkeeper], Yvan’.) However, it is soon revealed that this is just one of many secrets that this group of young people keep from one another – including Anne’s affair with Yvan (behind the back of Henri) and Marc and Cecile’s relationship. Shortly after Yvan forces Anne and Henri to remain silent about the murder of the shopkeeper, the trio return to the warehouse where the band rehearse. There, they encounter Marc and Cecile, and Marc asks Yvan not to reveal to Xavier the nature of Marc’s relationship with Xavier’s girlfriend. Not long after this, it is revealed that Anne, who is in a relationship with Henri, is also involved in a passionate affair with Henri. The sense of anomie engendered by these secrets and hidden affairs leads to the dissolution of the band and the erasure of any promise of future musical success: in London, Albertini notes that ‘You guys are starting to become a pain in the neck. You only play every two months and you can’t even show up together’. In many ways, the film is about the organic disintegration of friendships and relationships that happens when a person matures; the killing of the shopkeeper is a catalyst, but for the most part the narrative of the film would function just as well without that moment of high drama in its expository sequence. Kent Jones notes that ‘what’s pressing down on everyone here is not just guilt over a monstrous act: Assayas blends the guilty and the innocent together so thoroughly that the distinction hardly matters’ (Jones, op cit.: 6). Citing Fornara and Signorelli’s writing about the picture, Rosanna Maule suggests that ultimately, Disorder is about ‘the uncertainties faced by young people who have yet to find a place and life in society’ (Fornara and Signorelli, cited in Maule, 2008: 94). For most of the running time of Disorder, the audience’s perspective on the action is guided by Henri, who is held at gunpoint by the shopkeeper in the break-in that opens the film, and who acts as the moral conscience of the group after Yvan kills the same shopkeeper. Relationships are initially soured by Yvan’s demand that Anne and Henri vow not to reveal what happened in the shop that night, reinforced by Yvan’s attempts to deflect blame for the shopkeeper’s death onto his friends. (‘You made me’, Yvan tells Henri angrily when Henri asserts, ‘We’ve killed him [the shopkeeper], Yvan’.) However, it is soon revealed that this is just one of many secrets that this group of young people keep from one another – including Anne’s affair with Yvan (behind the back of Henri) and Marc and Cecile’s relationship. Shortly after Yvan forces Anne and Henri to remain silent about the murder of the shopkeeper, the trio return to the warehouse where the band rehearse. There, they encounter Marc and Cecile, and Marc asks Yvan not to reveal to Xavier the nature of Marc’s relationship with Xavier’s girlfriend. Not long after this, it is revealed that Anne, who is in a relationship with Henri, is also involved in a passionate affair with Henri. The sense of anomie engendered by these secrets and hidden affairs leads to the dissolution of the band and the erasure of any promise of future musical success: in London, Albertini notes that ‘You guys are starting to become a pain in the neck. You only play every two months and you can’t even show up together’. In many ways, the film is about the organic disintegration of friendships and relationships that happens when a person matures; the killing of the shopkeeper is a catalyst, but for the most part the narrative of the film would function just as well without that moment of high drama in its expository sequence. Kent Jones notes that ‘what’s pressing down on everyone here is not just guilt over a monstrous act: Assayas blends the guilty and the innocent together so thoroughly that the distinction hardly matters’ (Jones, op cit.: 6). Citing Fornara and Signorelli’s writing about the picture, Rosanna Maule suggests that ultimately, Disorder is about ‘the uncertainties faced by young people who have yet to find a place and life in society’ (Fornara and Signorelli, cited in Maule, 2008: 94).

Winter’s Child is, like Assayas’ subsequent picture Paris s’eveille (Paris Awakens, 1991), about the relationships between parents and their children. Assayas was reputedly inspired to make Winter’s Child in response to Ingmar Bergman’s films. (Assayas interviewed Bergman for Cahiers du cinema not long after completing Winter’s Child.) The film establishes its tone in the opening sequence, in which a heavily pregnant Natalia awakens and, believing herself to be in labour, calls out for Stephane. He is nowhere to be found, and Natalia collapses on the floor with the telephone in her hand. In the morning, he returns and gives her the cold shoulder, shrinking from her touch and complaining about the fact that she has arranged a medical appointment for him – behaving for all the world like a petulant child. ‘I hate doctors. I hate being touched’, he spits cruelly, ‘Are you sure we need to do this? [….] I mean, get married?’ ‘For the baby’, Natalia responds. ‘Stop stroking your belly in that self-gratifying way. It’s exasperating’, he chides her, ‘It’s always the same. People do it for the child benefit. Who cares if we’re married or not?’ ‘I want my child to have a father’, Natalia implores. ‘Do I look like a father to you?’, he asks, telling her ‘I don’t want it [the child] or you’.  Stephane has a terse relationship with his own father, though this seems to owe more to Stephane’s qualities than those of his father. Early in the film, Stephane takes Sabine to his father’s house, believing his father to be in China. Stephane informs Sabine that he hasn’t spoken to his father in over a year, following a disagreement over ‘my sister’s antics’. As Stephane’s father tells Stephane, ‘You despise me; I don’t know why’. Stephane’s father also accuses Stephane, apparently quite accurately, of being spoilt and having a sense of entitlement. Later, after his father passes away, Stephane sorts through his father’s belongings and discovers his wallet, into which is tucked a photograph of Stephane as a boy – an index of his father’s unrequited affection for Stephane. Stephane has a terse relationship with his own father, though this seems to owe more to Stephane’s qualities than those of his father. Early in the film, Stephane takes Sabine to his father’s house, believing his father to be in China. Stephane informs Sabine that he hasn’t spoken to his father in over a year, following a disagreement over ‘my sister’s antics’. As Stephane’s father tells Stephane, ‘You despise me; I don’t know why’. Stephane’s father also accuses Stephane, apparently quite accurately, of being spoilt and having a sense of entitlement. Later, after his father passes away, Stephane sorts through his father’s belongings and discovers his wallet, into which is tucked a photograph of Stephane as a boy – an index of his father’s unrequited affection for Stephane.

As Kent Jones notes, ‘a current of bottomless blue funk’ connects the various relationships within the film, all of which are characterised by infidelity and confusion: Natalia’s relationship with Stephane, the father of her child, and Stephane’s relationship with the unhinged set designer Sabine – who is obsessed with Bruno, an actor in the theatre company for which she works (Jones, op cit.: 6). Where Stephane is cold in his relationships with women, Sabine is the opposite: her infatuation with Bruno is obsessive and destructive. The pair had a brief relationship in South America, whilst their theatre company was on tour there, but on returning to Paris Bruno ended it. However, Sabine has become obsessed with Bruno and, after leaving Stephane and his father, she returns to Bruno’s home and assaults him with a knife, holding the blade to his throat: ‘I just need to press a little harder and you’d be mine forever’, she tells him. As a parent, Winter’s Child is difficult to watch: Stephane and Natalia’s child, the true victim of the story, is born into a loveless world that seems populated with narcissists of one form or another. In Italy, Jean-Marie reveals that Natalia never talks about the child or shows it to anyone: no-one seems certain of the child’s gender or name, which isn’t revealed until the climax of the narrative. Even Natalia depersonalises her own baby when she talks about it, referring to the baby simply as ‘the child’. Kent Jones observes that Winter’s Child is ‘relentlessly austere, and Assayas’ control of the emotional tone is so rigid that even small glimpses of the Italian landscape feel heavy-hearted’; the film offers, Jones argues, a ‘sustained chord of pain and regret’ (Jones, op cit.: 6).

Video

Disorder takes up just under 19Gb of space and Winter’s Child fills a little over 17Gb of space on the same dual-layered Blu-ray disc. Shot on 35mm colour stock, both films are presented in their intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1. Both films are complete, Disorder running for 91:03 minutes and Winter’s Child running for 83:42 mins. The presentations of both films have been supervised and approved by Assayas himself. Like Assayas’ Paris Awakens, Disorder and Winter’s Child are dominated by cold blue tones. All three films have a distinctive aesthetic owing to the use during postproduction of the bleach bypass process also employed by Roger Deakins on Michael Radford’s 1984 (1984) and in films such as David Fincher’s Se7en (1995) and Jeunet & Caro’s Delicatessen (1991). This results in a desaturated palette. As Kent Jones argues, ‘Assayas and cinematographer Denis Lenoir allow a lot of colour to drain from the image, and they work in some of the darkest hues seen in modern movies. The effect is most dramatic in Désordre, which is nearly monochromatic right from its opening crane down from a neon sign glowing in the dark’ (Jones, 2007: 5). This is communicated excellently in the presentations of Disorder and Winter’s Child found on Arrow Academy’s Blu-ray release. The palette in both pictures is cold and desaturated, dominated by steely blues. The presentations of both films display a very pleasing level of detail, especially in close-ups. Midtones are rich and defined, but with sharp curves into the toe – presumably a result of the bleach bypass process. A solid encode to disc ensures the presentations of both films retain the structure of 35mm film. Disorder:

Winter’s Child:

Some full-sized screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

Audio is presented via, in the case of both films, a LPCM 1.0 track (in French, with some minor dialogue in English). The tracks for both films are rich and deep, with good range. Optional English subtitles are provided. These are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

Aside from both films, the disc includes: Aside from both films, the disc includes:

- Disorder interviews: o Olivier Assayas (41:48). This retrospective interview features Assayas discussing the production of Disorder, which he says grew out of working on the writing of Rendez-vous for Andre Techine. Here, Assayas says that working as a critic for Cahier du cinema was a ‘hurdle’ that he needed to overcome in order to prove himself as a director. The interview is in French, and accompanied by optional English subtitles. o Ann-Gisel Glass, Lucas Belvaux, Wadeck Stanczak and Remi Martin (18:02). The three lead actors from Disorder reflect on their roles in the film and talk about working with Assayas. This interview is also in French, and accompanied by optional English subtitles. - Disorder trailer (2:02). - Winter’s Child trailer (1:15).

Overall

Assayas is an incredibly interesting filmmaker, and it seems impossible for him to make a film which isn’t engaging. That said, Winter’s Child is a difficult film to ‘enjoy’ (deliberately so, I’m sure) simply because of how unpleasant and self-involved its protagonist, Stephane, is. It’s a richly textured film, however, as is Disorder. Both films are about secrets of all shapes and sizes, and how deception is connected to anomie. There’s a deadening sense of repetition in the structure of both pictures, with the characters returning continuously to destructive (and self-destructive) patterns of behaviour. This is reinforced in Winter’s Child particularly by Assayas’ judicious use of ellipses within the narrative. Both pictures are impressive, extremely cine-literature pictures from a director who was, in terms of his feature film career, a filmmaking novice. That said, Assayas has claimed that he saw his work as a film critic as an apprenticeship to his later career as a filmmaker, and whilst writing for Cahier du cinema, Assayas continued to make short films and documentaries. Assayas is an incredibly interesting filmmaker, and it seems impossible for him to make a film which isn’t engaging. That said, Winter’s Child is a difficult film to ‘enjoy’ (deliberately so, I’m sure) simply because of how unpleasant and self-involved its protagonist, Stephane, is. It’s a richly textured film, however, as is Disorder. Both films are about secrets of all shapes and sizes, and how deception is connected to anomie. There’s a deadening sense of repetition in the structure of both pictures, with the characters returning continuously to destructive (and self-destructive) patterns of behaviour. This is reinforced in Winter’s Child particularly by Assayas’ judicious use of ellipses within the narrative. Both pictures are impressive, extremely cine-literature pictures from a director who was, in terms of his feature film career, a filmmaking novice. That said, Assayas has claimed that he saw his work as a film critic as an apprenticeship to his later career as a filmmaker, and whilst writing for Cahier du cinema, Assayas continued to make short films and documentaries.

Arrow Academy’s Blu-ray release of both Disorder and Winter’s Child is very pleasing indeed, offering UK viewers a chance to see these relatively little-seen pictures. The use of the bleach bypass process ensures both films possess a very distinctive aesthetic, which is carried over very well into the presentations included in this release. Some more contextual material would have been more than welcome, but that’s a minor ‘gripe’: this release nevertheless comes with a very strong recommendation. References: Hampton, Howard, 2007: Born in Flames: Termite Dreams, Dialectical Fairy Tales, and Pop Apocalypses. Harvard University Press Jones, Kent, 2007: Physical Evidence: Selected Film Criticism. Wesleyan University Press Maule, Rosanna, 2008: Beyond Auteurism: New Directions in Authorial Film Practices in France, Italy and Spain Since the 1980s. Bristol: Intellect Books Please click to enlarge: Disorder

Winter’s Child

|

|||||

|