|

|

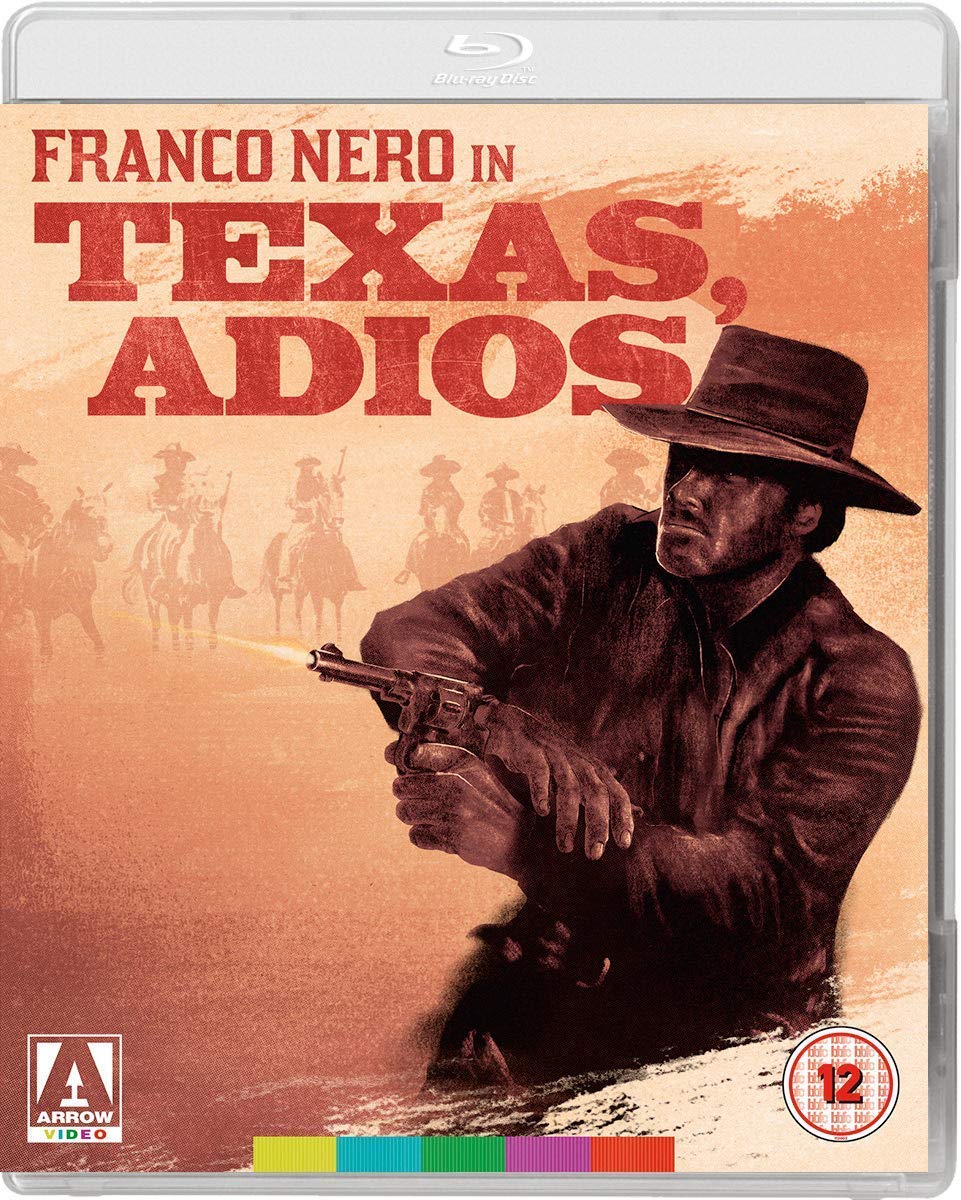

Texas, Adios AKA Texas, addio AKA The Avenger AKA Goodbye Texas (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (17th December 2018). |

|

The Film

Texas, Addio (Ferdinando Baldi, 1966) Texas, Addio (Ferdinando Baldi, 1966)

Lawman Burt Sullivan (Franco Nero) plans to cross the border into Mexico to hunt down Cisco Delgado (Jose Suarez), the man who many years before killed Burt’s father. Burt asks his friend Dick (Giovanni Ivan Scratuglia) to look after Burt’s younger brother Jim (Alberto Dell’Acqua), but Jim has other ideas and insists on accompanying Burt on his self-directed mission. In Mexico, Burt asks after Cisco Delgado but the mere mention of Delgado’s name causes the locals to shy away. In a tavern, Jim’s questions about Delgado pique the interest of some hoodlums, who harass Jim until Burt silences them with bullets. Burt and Jim are called to the residence of McLeod (Jose Guardiola), who warns the brothers to ‘go back to Texas’. After their meeting with McLeod, Burt and Jim are approached by a lawyer, Gimenez (Luigi Pistilli). Gimenez advises the brothers of Delgado’s power within that region of Mexico, and he tells Burt and Jim that he and some others are plotting to overthrow Delgado. Burt and Jim are also aided by Paquita (Silvana Bacci), a barmaid from the tavern, who directs the pair towards a shepherd, Manuel Hernandez. Manuel, Paquita says, will help the brothers find Delgado’s hideout. However, Burt and Jim later discover Paquita’s corpse tied to a post in the desert: she has been killed for betraying Delgado.  They track down Hernandez, who directs Burt and Jim to travel on a wagon filled with women that is heading to Delgado’s hacienda to entertain Delgado’s henchmen. There, Burt and Jim confront Delgado, and though Burt humiliates Delgado by striking him, Delgado warns his men that he doesn’t want either Burt or Jim harmed. They track down Hernandez, who directs Burt and Jim to travel on a wagon filled with women that is heading to Delgado’s hacienda to entertain Delgado’s henchmen. There, Burt and Jim confront Delgado, and though Burt humiliates Delgado by striking him, Delgado warns his men that he doesn’t want either Burt or Jim harmed.

Burt must find a way of capturing Delgado and making him pay for the murder of Burt’s father, whilst also navigating the conflict between Delgado and Gimenez’s revolutionaries. (The main body of this review discusses a revealing plot point within the film’s narrative.) Director Ferdinando Baldi had ridden on the coattails of the popularity of the peplum with films such as David e Golia (David and Goliath, 1960) and Orazi e Curiazi (Duel of Champions, 1961); and following the success of Sergio Leone’s Per un pugno di dollari (Fistful of Dollars, 1965), like a number of his contemporaries Baldi used his experience in directing action pictures to make some highly efficient westerns all’italiana (Italian-style Westerns/Spaghetti Westerns). Released in 1966, the same year as Leone’s Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo (The Good, the Bad and the Ugly) and Sergio Corbucci’s Django, Baldi’s Texas, Addio – released in English-speaking territories as Texas, Adios – was the first in as series of Westerns directed by Baldi. Most of these had Gothic undertones or unusual elements: Odia il prossimuo tuo (Hate thy Neigbour, 1968) had an imposing antagonist in the form of ‘George Eastman’ (Luigi Montefiore) and a villain who takes sadistic pleasure in forcing men to fight to the death using metal claws; Little Rita nel West (Little Rita of the West, 1968) offered a parody of the Spaghetti Western through the lens of a musical (starring Rita Pavone); Blindman (1971) transposed Zatoichi, the blind swordsman of Japanese cinema, to the landscape of the Western; and Get Mean (1975) was unlike any other Western you might have seen – which is by no means a recommendation.  Baldi’s Westerns were variable in quality, though his strongest examples of the western all’italiana (such as Texas, Addio and Il pistolero dell’Ave Maria/The Forgotten Pistolero, 1969) demonstrated a fascination with concealed familial relationships and the nature/nurture debate that suggested the strong influence of both Greek myth (The Forgotten Pistolero offered a reworking of the myth of Orestes) and the American Westerns of Anthony Mann (Winchester ’73, 1950; The Man from Laramie, 1955; Man of the West, 1958). Here, in Texas Addio, Baldi explores this theme in a direct manner, with the reveal that Cisco Delgado, the killer of Burt’s father, is the father of Burt’s sibling Jim; this follows Jim’s demonstration of an innate proficiency with a firearm and a casual approach to killing that, prior to the brothers’ journey into Mexico, was concealed by Jim’s sheltered upbringing but underscores his biological relationship with the sadistic Delgado. Baldi’s handling of this material makes one wonder whether George Lucas, when plotting the big reveal within The Empire Strikes Back (Irvin Kershner, 1980) and Return of the Jedi (Richard Marquand, 1983), was influenced as much by this modest western all’italiana as Kurosawa’s Hidden Fortress (1958): if Delgado, who has achieved a position of authority within the power vacuum that exists in Mexico, has parallels with Darth Vader, it’s easy to see Jim evolving within Lucas’ mind into Luke Skywalker and Burt becoming Han Solo. Baldi’s Westerns were variable in quality, though his strongest examples of the western all’italiana (such as Texas, Addio and Il pistolero dell’Ave Maria/The Forgotten Pistolero, 1969) demonstrated a fascination with concealed familial relationships and the nature/nurture debate that suggested the strong influence of both Greek myth (The Forgotten Pistolero offered a reworking of the myth of Orestes) and the American Westerns of Anthony Mann (Winchester ’73, 1950; The Man from Laramie, 1955; Man of the West, 1958). Here, in Texas Addio, Baldi explores this theme in a direct manner, with the reveal that Cisco Delgado, the killer of Burt’s father, is the father of Burt’s sibling Jim; this follows Jim’s demonstration of an innate proficiency with a firearm and a casual approach to killing that, prior to the brothers’ journey into Mexico, was concealed by Jim’s sheltered upbringing but underscores his biological relationship with the sadistic Delgado. Baldi’s handling of this material makes one wonder whether George Lucas, when plotting the big reveal within The Empire Strikes Back (Irvin Kershner, 1980) and Return of the Jedi (Richard Marquand, 1983), was influenced as much by this modest western all’italiana as Kurosawa’s Hidden Fortress (1958): if Delgado, who has achieved a position of authority within the power vacuum that exists in Mexico, has parallels with Darth Vader, it’s easy to see Jim evolving within Lucas’ mind into Luke Skywalker and Burt becoming Han Solo.

Like a number of other westerns all’italiana of the era, Texas, Addio is a film that focuses on border towns and the crossing of borders. Burt’s status as a lawman is outlined efficiently in the film’s opening sequence, in which he single-handedly dispatches a group of outlaws who have been terrorising a town, his heroic actions accompanied on the soundtrack by Don Powell singing the film’s title song, with the moments of violence intermittently frozen in order to allow the credits to be superimposed upon punctive still frames (rather like the opening sequence of Sam Peckinpah’s border-crossing American Western The Wild Bunch, released in 1969). Burt decides to journey into Mexico in order to catch – not kill – his father’s murderer, Cisco Delgado. He tries to dissuade his naïve, innocent younger brother Jim from coming with him but is ultimately unsuccessful. When the brothers reach Mexico, they find the territory to be ruled over by cruel gangsters: one of the first things they witness is the execution of several men by an armed group led by Miguel (Livio Lorenzon). These men are the underlings of the sadistic Delgado, who takes pleasure in tormenting those who provoke his ire: when an elderly landowner refuses to sell out to Delgado, Delgado has the man’s three sons hanged before demonstrating his skills as a marksman by shooting the nooses around each man’s neck. The sadism of Delgado’s regime is reinforced later, when Burt and Jim find Paquita’s corpse: she has been tied to a post in the desert, tortured and killed.  It seems that Delgado has achieved his position because of a power vacuum within Mexico, and a group of revolutionaries, led by the lawyer Gimenez, are making plans to unseat him. (‘I’m sure you understand what I’ve become’, Delgado tells Burt, ‘I have land, prosperity power. My name is feared all over Mexico’.) Soon after their arrival in Mexico, Jim notices that Burt – who in his role as a lawman has always prided himself on capturing outlaws alive – is readily shooting dead those men who threaten or accost the pair. ‘Burt, didn’t out prefer to catch outlaws alive when you were a sheriff?’, Jim asks. ‘This ain’t White Rock’, Burt reminds Jim curtly. Later, the lawyer Gimenez tells the brothers that ‘In this part of Mexico, there’s no law and order. Only anarchy and the encouragement of mercenary interests, merciless tyranny and unchecked power’. It seems that Delgado has achieved his position because of a power vacuum within Mexico, and a group of revolutionaries, led by the lawyer Gimenez, are making plans to unseat him. (‘I’m sure you understand what I’ve become’, Delgado tells Burt, ‘I have land, prosperity power. My name is feared all over Mexico’.) Soon after their arrival in Mexico, Jim notices that Burt – who in his role as a lawman has always prided himself on capturing outlaws alive – is readily shooting dead those men who threaten or accost the pair. ‘Burt, didn’t out prefer to catch outlaws alive when you were a sheriff?’, Jim asks. ‘This ain’t White Rock’, Burt reminds Jim curtly. Later, the lawyer Gimenez tells the brothers that ‘In this part of Mexico, there’s no law and order. Only anarchy and the encouragement of mercenary interests, merciless tyranny and unchecked power’.

In the film’s schema, Mexico is a place of lawlessness and corruption which is set against the force of law, as embodied by Burt. Burt and Jim’s crossing of the border into Mexico might be compared with the openly allegorical border crossings of 1950s American Westerns such as Robert Aldrich’s Vera Cruz (1954), Robert Parrish’s The Wonderful Country (1959) and Sam Peckinpah’s Major Dundee (1965) – and later films like The Wild Bunch. Like those US Westerns, Texas, Addio depicts Mexico as a politically unstable country which begs for aid but is exploited by men of greed. As Austin Fisher notes, in discussion of Vera Cruz, ‘in the context of Korea and Vietnam [crossing the border] became a highly politicised act, replete with signifiers of interventionism, containment and imperialism’ (Fisher, 2014: 126).  Like a number of westerns all’italiana of the era, Texas, Addio has a strong Freudian element to it. Burt and Jim’s quest to capture Delgado has, in light of the revelations about Jim’s relationship with Delgado, a strong Oedipal element to it. Additionally, like films such as Sergio Leone’s Per qualche dollaro in piu (For a Few Dollars More, 1965), Once Upon a Time in the West (Leone, 1968) and Giulio Petroni’s Da uomo a uomo (Death Rides a Horse, 1967), the narrative revolves around a traumatic ‘primal scene’ (Delgado’s killing of Burt’s father) which drives the actions of the protagonist (Burt) and to which the film returns again and again via flashbacks which are bridged into the diegesis through the use of a ripple dissolve and discordant music – much like the flashbacks of Colonel Mortimer (Lee Van Cleef) to the death of his sister in Per qualche dollaro in piu. For his part, Delgado is conflicted about his own role, telling Burt that he ‘didn’t come back for Jim because I knew he was with you and he’d grown up to be honest and respectable, without the taint of being a criminal’s son [….] Without taking the risk of becoming like your father or me. That way, I thought, I could avenge the evil instinct that runs into my veins’. The ‘rounded’ characterisation of Delgado is mirrored in the film’s depiction of Burt’s obsessive desire to capture Delgado alive, the nature of which Delgado highlights when he asks Burt, ‘Who do you think you are? A pastor? A Quaker? A preacher of the law?’ Like a number of westerns all’italiana of the era, Texas, Addio has a strong Freudian element to it. Burt and Jim’s quest to capture Delgado has, in light of the revelations about Jim’s relationship with Delgado, a strong Oedipal element to it. Additionally, like films such as Sergio Leone’s Per qualche dollaro in piu (For a Few Dollars More, 1965), Once Upon a Time in the West (Leone, 1968) and Giulio Petroni’s Da uomo a uomo (Death Rides a Horse, 1967), the narrative revolves around a traumatic ‘primal scene’ (Delgado’s killing of Burt’s father) which drives the actions of the protagonist (Burt) and to which the film returns again and again via flashbacks which are bridged into the diegesis through the use of a ripple dissolve and discordant music – much like the flashbacks of Colonel Mortimer (Lee Van Cleef) to the death of his sister in Per qualche dollaro in piu. For his part, Delgado is conflicted about his own role, telling Burt that he ‘didn’t come back for Jim because I knew he was with you and he’d grown up to be honest and respectable, without the taint of being a criminal’s son [….] Without taking the risk of becoming like your father or me. That way, I thought, I could avenge the evil instinct that runs into my veins’. The ‘rounded’ characterisation of Delgado is mirrored in the film’s depiction of Burt’s obsessive desire to capture Delgado alive, the nature of which Delgado highlights when he asks Burt, ‘Who do you think you are? A pastor? A Quaker? A preacher of the law?’

Video

Taking up a little over 25Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, Texas, Addio’s 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and is in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The film is runs for 92:04 mins and would seem to be uncut. Taking up a little over 25Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, Texas, Addio’s 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and is in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The film is runs for 92:04 mins and would seem to be uncut.

Where many widescreen westerns all’italiana were shot in the 2-perf Techniscope format (or similar 2-perf formats such as Cromoscope), Texas, Addio was shot in the German 35mm anamorphic format, Ultrascope. Texas, Addio features some excellent location work and superbly photographed action. The film was photographed by Enzo Barboni, who shot Corbucci’s Django and Eugenio Martin’s El precio de un hombre (The Bounty Killer) in the same year. Within the film, Barboni employs some potent techniques, such as using split dioptre lenses to create a strong sense of depth of field even within fairly low light interior shots. Arrow’s presentation of Texas, Addio is based on a new 2k restoration from the film’s original negative. It’s a solid presentation. There are some fairly funky-looking optical shots and a few shots display some very noticeable instability within the emulsions (see the two large screengrabs immediately beneath the text in this section of the review). That said, this damage is organic, and the bulk of the film looks excellent. Shot under the Mediterranean sun, much of the exteriors have strong lighting and deep shadows; contrast levels within this presentation are very pleasing. Midtones are rich and defined, and there is good gradation into the toe and shoulder, with balanced highlights and the presence of shadow detail. Colours are naturalistic, consistent and would seem to be true-to-source; early sequences have an autumnal palette, dominated by greens and browns. This changes when the narrative shifts to Mexico, which is dominated by the colours of the desert: yellows and oranges. Skintones are natural. The level of detail is excellent, with very strong fine detail present in close-ups. The structure of 35mm film is retained through a natural, filmlike presentation that is carried in a pleasing encode to disc. Emulsion damage (click to enlarge):

Audio

The disc offers the viewer the opportunity of watching the film via the Italian-language version, with optional English subtitles translating the Italian dialogue, or the English-language dub, with optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. Both audio tracks are presented in DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0, and they are similar in terms of displaying good range and depth. The dialogue in the English and Italian versions differs in its connotations in quite a few spots. Near the start of the film, when Burt asks Dick to look after Jim whilst Burt travels to Mexico, in the English version Burt tells Dick ‘My brother’s still just a kid’. In the Italian-language version of the picture, Burt asks Dick to ‘Look after him [Jim] as if he were your own’. In the Mexican tavern, after dispatching three of the thugs who make an attempt on Jim’s life, in the English version Burt warns the surviving hoodlum, ‘Next time, mind your own business’. In the Italian version, he says instead, ‘Pray you never meet me again’.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with C Courtney Joyner and Henry C Parke - ‘The Sheriff is in Town’ (20:19). This new interview with Franco Nero covers the actor’s involvement in this picture. Nero suggests that Texas, Addio is the ‘only film’ from that period of the western all’italiana to look like an American Western. He reflects on some of the unique elements of the film, such as costume designer Carlo Simi’s idea of placing the hero’s gunbelt on the outside of his coat. Nero offers some interesting stories about the ways in which his career overlapped with that of Clint Eastwood. He also talks about the other actors in the picture and his relationships with them, leading on to some reflections on the roles of women in westerns all’italiana more generally. Nero also talks at length about horse riding and weapons handling. Nero speaks in English. - ‘Jump into the West’ (33:46). Alberto Dell’Acqua is interviews. He speaks about how he came to be cast in the role and talks about his working relationship with Franco Nero. Dell’Acqua discusses his work on other westerns all’italiana. Dell’Acqua speaks in Italian, with optional English subtitles provided. - ‘That’s My Life: Part 2’ (9:19). The film’s co-writer, Franco Rossetti, speaks in an archival interview, discussing his work within the Italian film industry as both a director and a writer. Rossetti speaks in Italian, and optional English subtitles are provided for the viewer. - ‘Hello Texas!’ (16:24). Austin Fisher reflects on the placing of Texas, Addio within the western all’italiana – between Django and the more political Mexico-set Italian Westerns that followed in the late 1960s. He discusses the film’s resemblance to American Westerns and the manner in which the western all’italiana evolved during the mid/late 1960s. Fisher also talks about the position of this film within the career of director Ferdinando Baldi. - Trailer (2:42). - Image Galleries: Stills (0:08); Posters (0:13); Lobby Cards (0:29); Press (0:08); Home Video (0:06).

Overall

Texas, Addio is a western all’italiana from the early years of the form. Baldi’s film feels much more ‘American’ than some of the more exotic examples of Italian Westerns that would appear later in the 1960s, and this alienates some viewers who come to the picture expecting a film like – for example – Corbucci’s Django, released the same year and also starring Franco Nero. My first viewing of Texas, Addio was via the Aktiv VHS release in the early/mid-1990s, and despite wrinkling at the English dub – which in my memory seems more terrible than it actually is – I fell in love with the film and it has remained one of my favourite westerns all’italiana. The relationship between this picture and the ‘adult’ Westerns made in the US during the 1950s (especially those of Anthony Mann or perhaps Budd Boetticher) seems writ large throughout the film, and admirers of those pictures will find much to enjoy within Texas, Adios – especially the way in which the narrative builds towards a Pyrrhic victory. Taciturn Burt is a slightly different Western hero to Django, which Nero played the same year, but Nero’s performance and Baldi’s direction foreground the action, which is staged excellently throughout. Texas, Addio is a western all’italiana from the early years of the form. Baldi’s film feels much more ‘American’ than some of the more exotic examples of Italian Westerns that would appear later in the 1960s, and this alienates some viewers who come to the picture expecting a film like – for example – Corbucci’s Django, released the same year and also starring Franco Nero. My first viewing of Texas, Addio was via the Aktiv VHS release in the early/mid-1990s, and despite wrinkling at the English dub – which in my memory seems more terrible than it actually is – I fell in love with the film and it has remained one of my favourite westerns all’italiana. The relationship between this picture and the ‘adult’ Westerns made in the US during the 1950s (especially those of Anthony Mann or perhaps Budd Boetticher) seems writ large throughout the film, and admirers of those pictures will find much to enjoy within Texas, Adios – especially the way in which the narrative builds towards a Pyrrhic victory. Taciturn Burt is a slightly different Western hero to Django, which Nero played the same year, but Nero’s performance and Baldi’s direction foreground the action, which is staged excellently throughout.

Arrow’s Blu-ray presentation of Texas, Addio contains a pleasing presentation of the main feature, though it displays some organic damage within the source materials. The film is supported by some excellent contextual material. The new interview with Franco Nero, in particular, is illuminating and contains a number of anecdotes that I don’t recall having heard or read elsewhere. References: Fisher, Austin, 2014: Radical Frontiers in the Spaghetti Western: Politics, Violence and Popular Italian Cinema. London: I B Tauris Please click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|