|

|

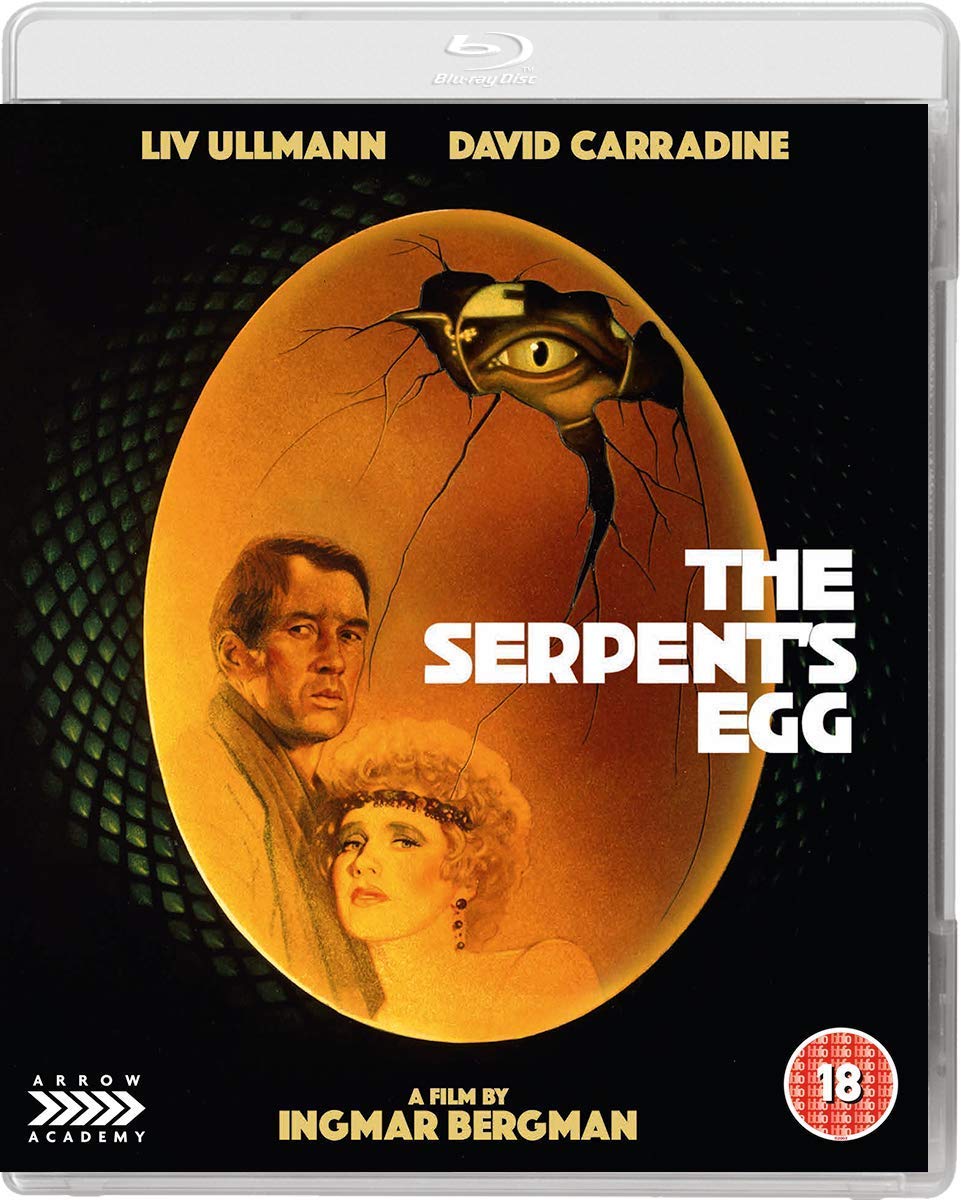

Serpent's Egg (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (30th December 2018). |

|

The Film

The Serpent’s Egg (Ingmar Bergman, 1977) The Serpent’s Egg (Ingmar Bergman, 1977)

November, 1923. Former trapeze artist Abel Rosenberg (David Carradine), a 35 year old American Jew living in Berlin, returns to the lodging house where he lives with his brother Max; however, Abel finds that Max is dead, having apparently blown his brains out with a gunshot to the mouth. Abel struggles to work out his brother’s motivation for committing suicide – his only clue is a note from Max which reads, ‘There is poisoning going on’ – and slips into a deep funk. He is questioned by Inspector Bauer (Gert Frobe), who expresses some anti-immigrant sentiments, telling Abel ‘We are not going to take care of you when your money runs out’. Bauer’s sentiments are shared with the newspapers, which are filled with anti-Jewish propaganda. Bauer takes Abel to the morgue, where Bauer shows Abel a number of corpses – amongst them is Greta Hofer, Max’s former fiancée – all of whom have died recently in mysterious circumstances, some of them the victims of suicide. Abel tracks down Max’s wife Manuela (Liv Ullmann), who is currently working in a cabaret, and tells her of Max’s suicide. Manuela informs Abel that she didn’t know what job Max was doing – only that the money was good. Abel tells Manuela about his childhood with Max: their family would spend summer holidays in Amalfi, where they played with a German boy, Hans Vergerus. Hans showed a talent for cruelty, tying down a cat and cutting it open so that the boys could see its beating heart. Abel is shocked to see an adult Hans (Heinz Bennent) at the cabaret where Manuela works. After a confrontation with Inspector Bauer in which Abel screams ‘I know why you’re doing this! It’s because I’m a Jew!’ before fleeing from the police station, Abel finds himself thrown into the cells. Manuela visits and Abel is released into her care. At the cabaret, Abel encounters Hans once again. Returning home with Manuela, Abel asks her if she has slept with Hans. Manuela tells him she has, and that she ‘feel[s] sorry for him. Maybe he needs some kindness’.  Aside from working at the cabaret during the evening, Manuela has a mysterious day job. One day, Abel decides to follow Manuela to see what she does with her days. He follows her to a church, where she has a conversation with a priest (James Whitmore), telling him that she blames herself for Max’s death. Aside from working at the cabaret during the evening, Manuela has a mysterious day job. One day, Abel decides to follow Manuela to see what she does with her days. He follows her to a church, where she has a conversation with a priest (James Whitmore), telling him that she blames herself for Max’s death.

Afterwards, Abel follows Manuela to a clinic, the St Anna’s Clinic. He confronts Manuela, who tells him that this is the location of their new flat: Hans Vergerus helped her to find it and has also arranged for Abel to work in the clinic’s archives. However, during his work in the archives Abel discovers something deeply troubling about the activities that take place there – and his childhood friend’s involvement in them. Taking its title from a line in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, The Serpent’s Egg was Ingmar Bergman’s only ‘Hollywood’ picture (though it was shot in Germany and was a German-American co-production, between Rialto Film and Dino De Laurentiis). Bergman made the film whilst in tax exile from Sweden, the fallout from Bergman’s arrest for tax evasion in 1976. The Serpent’s Egg invites obvious comparisons with Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin Trilogy and Bob Fosse’s 1972 musical picture Cabaret, adapted from Isherwood’s work. (Incidentally, the excellent production design for The Serpent’s Egg was by Rolf Zehetbauer, who won an Academy Award for his work on Cabaret.) Bergman’s film also has some curious similarities with Tinto Brass’ Salon Kitty (1976). The setting and emphasis on cabaret acts is an obvious point of comparison, but on a more subtle level, Bergman’s picture makes similar use of zooms to carry the viewer suddenly from mid-shots to close-ups, and has a similar editing rhythm to Brass’ work – edits appearing at the point of gestures or as characters wander into the frame.  During its preproduction phase, The Serpent’s Egg went through several changes. Elliott Gould has suggested that the lead role was written for him. (Gould had acted in Bergman’s first English-language film, The Touch, in 1971.) At one point, Bergman approached Dustin Hoffman to play Abel, but Hoffman withdrew owing to a sense that the part wasn’t right for him; when Hoffman withdrew, Bergman approached Robert Redford, who turned the role down, before asking Peter Falk (Bergman, 1995). Falk couldn’t play the part owing to contractual obligations (ibid.). Dino De Laurentiis suggested using Richard Harris, who had just finished shooting Orca—The Killer Whale for Michael Anderson (ibid.). However, Harris was forced to turn the role down after contracting pneumonia after spending much of the production of Orca—The Killer Whale in a huge water tank in Malta (ibid.). A 1976 article in the New York Times, by Bernard Weinraub, about Bergman’s decision to settle in Germany following his tax problems in Sweden describes The Serpent’s Egg as a project about ‘two strangers—portrayed by Richard Harris and Liv Ullmann—who meet in Berlin during the week in 1923 that the deutschmark went out of control, the week that Hitler began writing “Mein Kampf”’ (Weinraub, 1976). Certainly, in the finished picture Abel and Manuela are far from strangers: they are related through Manuela’s marriage to Abel’s brother Max, and they also worked together in Papa Hollinger’s circus. During its preproduction phase, The Serpent’s Egg went through several changes. Elliott Gould has suggested that the lead role was written for him. (Gould had acted in Bergman’s first English-language film, The Touch, in 1971.) At one point, Bergman approached Dustin Hoffman to play Abel, but Hoffman withdrew owing to a sense that the part wasn’t right for him; when Hoffman withdrew, Bergman approached Robert Redford, who turned the role down, before asking Peter Falk (Bergman, 1995). Falk couldn’t play the part owing to contractual obligations (ibid.). Dino De Laurentiis suggested using Richard Harris, who had just finished shooting Orca—The Killer Whale for Michael Anderson (ibid.). However, Harris was forced to turn the role down after contracting pneumonia after spending much of the production of Orca—The Killer Whale in a huge water tank in Malta (ibid.). A 1976 article in the New York Times, by Bernard Weinraub, about Bergman’s decision to settle in Germany following his tax problems in Sweden describes The Serpent’s Egg as a project about ‘two strangers—portrayed by Richard Harris and Liv Ullmann—who meet in Berlin during the week in 1923 that the deutschmark went out of control, the week that Hitler began writing “Mein Kampf”’ (Weinraub, 1976). Certainly, in the finished picture Abel and Manuela are far from strangers: they are related through Manuela’s marriage to Abel’s brother Max, and they also worked together in Papa Hollinger’s circus.

The Serpent’s Egg is set in the week that took place from the 3rd of November to the 11th of November, 1923 – the week of the Munich Putsch. In interview, Bergman said that this specific period was important because it was ‘the week when the currency stopped existing. It’s fascinating when a currency stops existing—people lose their homes and belongings because they have no chance any more. There is no bottom any more, and the abyss is underneath’ (Bergman, quoted in Weinraub, op cit.). The line in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar from which Bergman took this picture’s title is spoken by Brutus as he makes plans to kill Caesar so as to prevent Rome becoming a dictatorship (‘And therefore think him as a serpent's egg, Which, hatch'd, would as his kind grow mischievous, And kill him in the shell’). Bergman’s film deals with the appearance of Nazi ideology in Germany during the 1920s, as a response to the social and economic hardships experienced during the period of hyperinflation that took place in 1923. Though the titular phrase (‘the serpent’s egg’) is used in a different context within the film’s dialogue (Hans states that social change in Germany during the 1920s is ‘like a serpent's egg. Through the thin membranes, you can clearly discern the already perfect reptile’), the image is an allusion to the rise of Nazi ideology as embodied by the figure of Hitler, making parallels between Hitler and Caesar – and Nazi Germany and Rome. The Serpent’s Egg is set in the week that took place from the 3rd of November to the 11th of November, 1923 – the week of the Munich Putsch. In interview, Bergman said that this specific period was important because it was ‘the week when the currency stopped existing. It’s fascinating when a currency stops existing—people lose their homes and belongings because they have no chance any more. There is no bottom any more, and the abyss is underneath’ (Bergman, quoted in Weinraub, op cit.). The line in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar from which Bergman took this picture’s title is spoken by Brutus as he makes plans to kill Caesar so as to prevent Rome becoming a dictatorship (‘And therefore think him as a serpent's egg, Which, hatch'd, would as his kind grow mischievous, And kill him in the shell’). Bergman’s film deals with the appearance of Nazi ideology in Germany during the 1920s, as a response to the social and economic hardships experienced during the period of hyperinflation that took place in 1923. Though the titular phrase (‘the serpent’s egg’) is used in a different context within the film’s dialogue (Hans states that social change in Germany during the 1920s is ‘like a serpent's egg. Through the thin membranes, you can clearly discern the already perfect reptile’), the image is an allusion to the rise of Nazi ideology as embodied by the figure of Hitler, making parallels between Hitler and Caesar – and Nazi Germany and Rome.

The film opens and closes with high contrast monochrome newsreel-like shots of crowds walking through city streets, a mass of faces moving in slow-motion and underscored, in the film’s opening sequence, by upbeat jazz: this credits sequence offers a juxtaposition of the optimism of the 1920s (represented by the vibrant jazz) with the realities of economic hardship during the era – and the rise of Fascism in Europe. This is immediately followed by a voiceover (from an extradiegetic narrator) which, at the start of the film, establishes the immediate context for the narrative that follows: the period of hyperinflation that Germany suffered during November of 1923. ‘The scene is Berlin’, the narrator tells us, ‘A pack of cigarettes costs four million Marks, and most everyone has lost faith in both the future and the present’. The film opens and closes with high contrast monochrome newsreel-like shots of crowds walking through city streets, a mass of faces moving in slow-motion and underscored, in the film’s opening sequence, by upbeat jazz: this credits sequence offers a juxtaposition of the optimism of the 1920s (represented by the vibrant jazz) with the realities of economic hardship during the era – and the rise of Fascism in Europe. This is immediately followed by a voiceover (from an extradiegetic narrator) which, at the start of the film, establishes the immediate context for the narrative that follows: the period of hyperinflation that Germany suffered during November of 1923. ‘The scene is Berlin’, the narrator tells us, ‘A pack of cigarettes costs four million Marks, and most everyone has lost faith in both the future and the present’.

Abel wanders through the narrative in a daze, mostly a passive observer of life, and more than willing to exploit the goodwill of others. He steals money from Manuela, an act which Manuela’s landlady Frau Holle (Edith Heerdegen) witnesses – resulting in her expelling Abel from her lodging house. (In a show of solidarity with Abel, Manuela severs her ties with Frau Holle too.) Abel is frequently framed behind bars – either of a cell or another object (eg, a metal bedframe); this recurring composition conveys his sense of entrapment. His situation is helpless: early in the film, he tells Maneula, ‘I wake up from a nightmare and find that real life is worse than the dream’. When Inspector Bauer shows Abel the corpses of several people who have died in mysterious circumstances – which Bauer believes might be linked to the death of Max – Abel’s response is utterly nihilistic: ‘Tomorrow everything’s gonna disappear. Why bother with a few murders?’, he asks sharply.  Reflecting Abel’s early observation about the relationship between nightmare and waking reality, the film’s tone becomes increasingly nightmarish as the narrative progresses. Towards the end of the picture, Abel witnesses a brutal act of violence as jackbooted policemen storm into the cabaret and beat the owner’s face into a bloody pulp. Abel becomes aware that the clinic where Hans has found him a job is involved in some disturbing experiments: one of Abel’s colleagues tells Abel that ‘Something terrible is going on […] Here, at the clinic’ and there are ‘very strange experiments. Experiments with human beings’ that are being carried out under Hans’ supervision. One night, after abandoning Manuela and wandering onto the streets of the city, Abel witnesses a cavalcade of strangeness: a minstrel show in a nightclub for the privileged; a woman butchering a horse in the street and offering to sell a handful of offal to Abel; armoured vehicles rolling through the city streets at night. Things come to a head when he is propositioned by a prostitute, Stella (Grischa Huber). Abel tells her to ‘Go to hell!’ ‘Where do you think we are?’, she responds. Stella leads Abel to a dingy room, lit with ominous red lighting, in which a black American man, Monroe (Glynn Turman), is ranting about another prostitute (‘She’s got fangs in her cunt, man! [….] A man could die in there’). Abel goads Monroe into attempting to fuck the prostitute in front of both Abel and Stella, but Monroe is unable to do this. In the film’s next sequence, Abel seeks the truth about the clinic and kills a man by pushing his opponent’s head underneath a descending lift; from here, he hunts down Hans, who tells him some deeply disturbing stories about the experiments which have taken place at the clinic. Presaging the escalation of the Nazi ideology, these final sequences of the film offer a nightmarish amplification in terms of human cruelty, the scene with Abel, Monroe and the prostitutes (in terms of its use of red lighting, in particular) seeming to symbolise a descent into hell itself – before Abel comes face to face, in the film’s final sequence, with the cold, rationalistic brutality of Hans and his experiments. Reflecting Abel’s early observation about the relationship between nightmare and waking reality, the film’s tone becomes increasingly nightmarish as the narrative progresses. Towards the end of the picture, Abel witnesses a brutal act of violence as jackbooted policemen storm into the cabaret and beat the owner’s face into a bloody pulp. Abel becomes aware that the clinic where Hans has found him a job is involved in some disturbing experiments: one of Abel’s colleagues tells Abel that ‘Something terrible is going on […] Here, at the clinic’ and there are ‘very strange experiments. Experiments with human beings’ that are being carried out under Hans’ supervision. One night, after abandoning Manuela and wandering onto the streets of the city, Abel witnesses a cavalcade of strangeness: a minstrel show in a nightclub for the privileged; a woman butchering a horse in the street and offering to sell a handful of offal to Abel; armoured vehicles rolling through the city streets at night. Things come to a head when he is propositioned by a prostitute, Stella (Grischa Huber). Abel tells her to ‘Go to hell!’ ‘Where do you think we are?’, she responds. Stella leads Abel to a dingy room, lit with ominous red lighting, in which a black American man, Monroe (Glynn Turman), is ranting about another prostitute (‘She’s got fangs in her cunt, man! [….] A man could die in there’). Abel goads Monroe into attempting to fuck the prostitute in front of both Abel and Stella, but Monroe is unable to do this. In the film’s next sequence, Abel seeks the truth about the clinic and kills a man by pushing his opponent’s head underneath a descending lift; from here, he hunts down Hans, who tells him some deeply disturbing stories about the experiments which have taken place at the clinic. Presaging the escalation of the Nazi ideology, these final sequences of the film offer a nightmarish amplification in terms of human cruelty, the scene with Abel, Monroe and the prostitutes (in terms of its use of red lighting, in particular) seeming to symbolise a descent into hell itself – before Abel comes face to face, in the film’s final sequence, with the cold, rationalistic brutality of Hans and his experiments.

David Carradine sleepwalks through the film in a way that, in retrospect, seems fitting for the character but which initially seems to have caused consternation for Bergman, who found the actor ‘absent-minded and a bit strange’ (Bergman, op cit.). To help Carradine prepare for production, Bergman screened Phil Jutzi’s Mutter Krausens Fahrt ins Gluck (1929) and Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Grosstadt (1927); but during the screenings, Carradine fell asleep (ibid.). This would prove to be a pattern of behaviour for the actor, who Bergman described as a ‘night owl’ and who would fall asleep at the drop of a hat – no matter where he was (ibid.). Nevertheless, Bergman admitted that Carradine was ‘hard-working, punctual, and well prepared’ (ibid.). However, Bergman and Carradine came to loggerheads at one point during the production: in the scene in which Abel walks through the city streets at night and comes across a woman who is butchering a dead horse, and who offers a handful of offal to Abel, Bergman originally planned to have the horse slaughtered on camera. (Documents seem to suggest that he wanted the locals, driven by hunger, to tear the animal to pieces onscreen.) However, Bergman instead had a horse shot off camera so that it was still fresh and the heat could be seen rising from its exposed organs. Carradine was reputedly disgusted at this, later describing the moment as ‘a schism’ in his relationship with Bergman and labelling Bergman’s actions as ‘totally insane’ – but admitting that ‘aside from that we had no disagreements. We were like brothers’ (Carradine, quoted in Geeks Staff, 2016). About the killing of the horse, Carradine asked Bergman, ‘What about your soul?’, and Bergman responded by stating weakly that ‘I’m an old prostitute; I’ve killed two other horses for movies, burned a horse and strangled a dog’ (Windeler, 1977). One wonders how to frame Bergman’s ‘confession’ to Carradine within the context of the thematic content of The Serpent’s Egg and its examination of the capacity of the human soul for cruelty. Perhaps the key is the epigraph Bergman originally planned for the film, a quote from Georg Buchner: ‘Man is an abyss and I turn giddy when I look down into it’. David Carradine sleepwalks through the film in a way that, in retrospect, seems fitting for the character but which initially seems to have caused consternation for Bergman, who found the actor ‘absent-minded and a bit strange’ (Bergman, op cit.). To help Carradine prepare for production, Bergman screened Phil Jutzi’s Mutter Krausens Fahrt ins Gluck (1929) and Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Grosstadt (1927); but during the screenings, Carradine fell asleep (ibid.). This would prove to be a pattern of behaviour for the actor, who Bergman described as a ‘night owl’ and who would fall asleep at the drop of a hat – no matter where he was (ibid.). Nevertheless, Bergman admitted that Carradine was ‘hard-working, punctual, and well prepared’ (ibid.). However, Bergman and Carradine came to loggerheads at one point during the production: in the scene in which Abel walks through the city streets at night and comes across a woman who is butchering a dead horse, and who offers a handful of offal to Abel, Bergman originally planned to have the horse slaughtered on camera. (Documents seem to suggest that he wanted the locals, driven by hunger, to tear the animal to pieces onscreen.) However, Bergman instead had a horse shot off camera so that it was still fresh and the heat could be seen rising from its exposed organs. Carradine was reputedly disgusted at this, later describing the moment as ‘a schism’ in his relationship with Bergman and labelling Bergman’s actions as ‘totally insane’ – but admitting that ‘aside from that we had no disagreements. We were like brothers’ (Carradine, quoted in Geeks Staff, 2016). About the killing of the horse, Carradine asked Bergman, ‘What about your soul?’, and Bergman responded by stating weakly that ‘I’m an old prostitute; I’ve killed two other horses for movies, burned a horse and strangled a dog’ (Windeler, 1977). One wonders how to frame Bergman’s ‘confession’ to Carradine within the context of the thematic content of The Serpent’s Egg and its examination of the capacity of the human soul for cruelty. Perhaps the key is the epigraph Bergman originally planned for the film, a quote from Georg Buchner: ‘Man is an abyss and I turn giddy when I look down into it’.

Video

The film takes up just over 32Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc; it is a 1080p presentation that uses the AVC codec. The film takes up just over 32Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc; it is a 1080p presentation that uses the AVC codec.

The Serpent’s Egg is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.66:1. The film is exquisitely photographed on 35mm colour stock by Sven Nykvist though, as noted above, some scenes use zoom lens that are optically inferior to primes – sometimes resulting in a slightly ‘hazy’ appearance to the photography. The film has a very cold palette, colours often seeming slightly desaturated. The result sometimes looks like a film whose negative has been ‘flashed’ though I don’t think this process was used by Nykvist during production. (Certainly, in comparison with the older DVD release from MGM, the colours in this presentation edge towards steely blues and greens.) Damage is virtually non-existent though there’s an unusual rolling light anomaly at an edit at 49:16 mins into the picture. (This may perhaps be a product of uneven development of the negative.) Some pleasing contrast levels highlight the incredibly careful lighting schemes used during production: chiaroscuro is used throughout the picture, beads of light picking out details in both long shots and close-ups. Midtones are rich and defined though curves into the toe and shoulder seem very sharp, resulting in a vertiginous dive into the shadows and a steep climb to the highlights. Finally, a strong encode to disc ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film. Some full-sized screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 track. This is perfectly serviceable. Dialogue is clear throughout and the track demonstrates good range. Dialogue is mostly in English, with some brief moments of (unsubtitled) German dialogue. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included. These are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with David Carradine. Carradine describes Bergman as a ‘very perverse director’ and The Serpent’s Egg as ‘a very perverse story. It’s very difficult to watch this one twice’. Carradine highlights Bergman’s suggestion that the picture is essentially ‘a horror movie’. He reflects on Bergman’s approach to directing, suggesting that ‘in a way I was left on my own’: the director wouldn’t give a great deal of ‘acting direction’ though knew exactly what he wanted to achieve visually. There are some long periods of silence in the track but Carradine’s comments are rich and meaningful. - ‘Bergman’s Egg’ (25:42). Barry Forshaw (whose surname is misspelled ‘Foreshaw’ on the disc menu) talks about The Serpent’s Egg’s place within the career of Bergman. (Forshaw has written about Scandinavian crime fiction and about the work of Henning Mankell, who is the son-in-law of Bergman.) Forshaw discusses the trajectory of Bergman’s filmmaking career and offers contextualisation of The Serpent’s Egg. - ‘Away From Home’ (15:54). In this featurette, which was produced for an earlier DVD release of this film, Marc Gervais – the author of a book about Bergman – begins by talking about The Serpent’s Egg. His comments are then followed by interviews with David Carradine and Liv Ullmann. - ‘German Expressionism’ (5:36). In another archival featurette, Marc Gervais talks about The Serpent’s Egg’s relationship with German Expressionism – suggesting one should not approach the film as ‘a Bergman movie’ but as an exercise in Expressionistic technique. - Trailer (3:18). - Image Gallery (15:40).

Overall

Bergman himself admitted that The Serpent’s Egg was ‘a substantial failure’ though he described the picture as ‘a healthy learning experience’ (Bergman, op cit.). Certainly, it’s a piece of grand guignol that escalates from domestic melodrama to a sense of Gothic menace in its final sequences. In its exploration of the rise of Fascism in inter-war Germany and its connection of this theme to domestic terrors that take place within run-down boarding houses and on cobbled streets, The Serpent’s Egg might remind viewers of Ulli Lommel’s Die Zartlichkeit der Wolfe (The Tenderness of Wolves, 1973, released by Arrow a couple of years ago and reviewed by us here) – and Nykvist’s photography has some similarities with Jürgen Jürges’ cinematography on the Lommel picture too. On reflection, Carradine’s performance as the largely passive Abel is pitch-perfect and it’s hard to imagine some of the other contenders in the role (arguably, Harris would have been too ‘heavy’ in the role, whereas Gould would have been too ‘light’). Ultimately, The Serpent’s Egg is a picture that takes a few missteps but it’s beautifully presented through some superb production design and Nykvist’s icy photography. Bergman himself admitted that The Serpent’s Egg was ‘a substantial failure’ though he described the picture as ‘a healthy learning experience’ (Bergman, op cit.). Certainly, it’s a piece of grand guignol that escalates from domestic melodrama to a sense of Gothic menace in its final sequences. In its exploration of the rise of Fascism in inter-war Germany and its connection of this theme to domestic terrors that take place within run-down boarding houses and on cobbled streets, The Serpent’s Egg might remind viewers of Ulli Lommel’s Die Zartlichkeit der Wolfe (The Tenderness of Wolves, 1973, released by Arrow a couple of years ago and reviewed by us here) – and Nykvist’s photography has some similarities with Jürgen Jürges’ cinematography on the Lommel picture too. On reflection, Carradine’s performance as the largely passive Abel is pitch-perfect and it’s hard to imagine some of the other contenders in the role (arguably, Harris would have been too ‘heavy’ in the role, whereas Gould would have been too ‘light’). Ultimately, The Serpent’s Egg is a picture that takes a few missteps but it’s beautifully presented through some superb production design and Nykvist’s icy photography.

Arrow’s Blu-ray release of The Serpent’s Egg offers a solid presentation of the film, though the palette within this presentation is much more ‘cold’ than that of the previous DVD releases. (This may be in line with Nykvist’s original intentions, but the publicity material for this release is quite nebulous in terms of identifying the source materials for this presentation.) I’ve yet to see Criterion’s new Blu-ray release of the film, so cannot make a direct comparison with it. Nevertheless, Arrow’s Blu-ray release is supported by some excellent contextual material – most of it inherited from previous digital home video releases, admittedly, but the new interview with Barry Forshaw helps to situate the film within the context of Bergman’s career. References: Bergman, Ingmar, 1995: Images: My Life in Film. London: Arcade Publishing Geeks Staff, 2016: ‘Bound for Glory’s David Carradine Interview’. [Online.] https://geeks.media/bound-for-glory-s-david-carradine-interview Weinraub, Bernard, 1976: ‘Bergman in Exile’. The New York Times (17 October, 1976) Windeler, Robert, 1977: ‘Getting It Together’. People (21 March, 1977) Please click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|