|

|

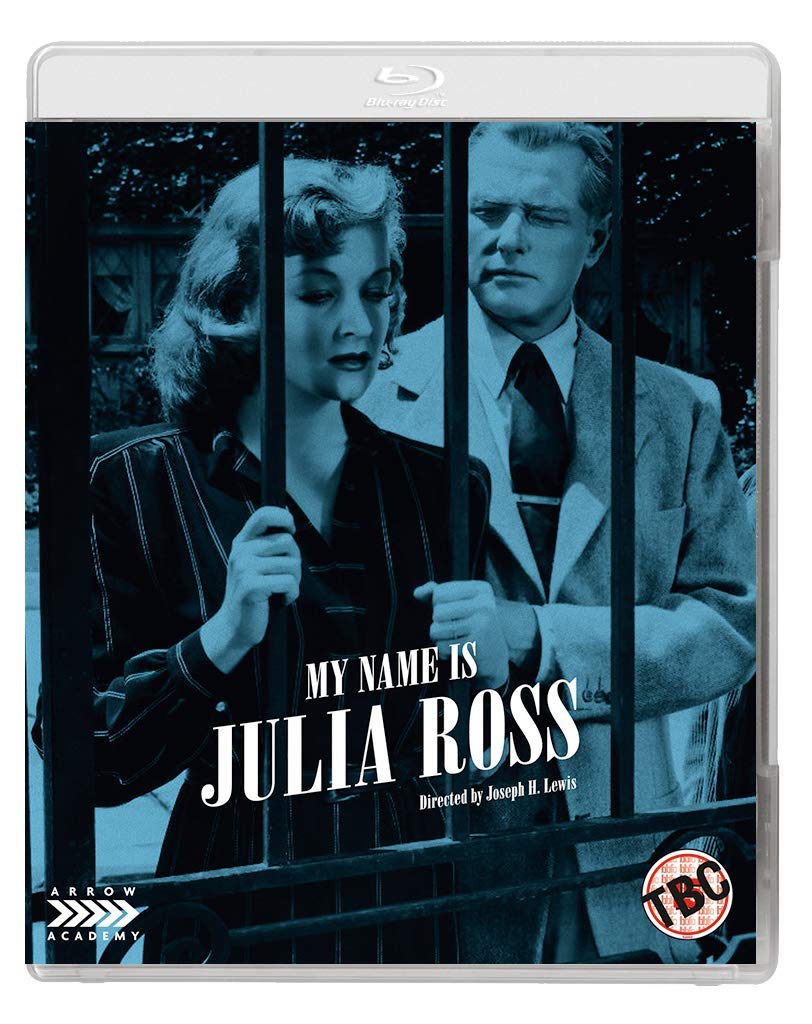

My Name Is Julia Ross (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (4th March 2019). |

|

The Film

My Name is Julia Ross (Joseph H Lewis, 1945) & So Dark the Night (Joseph H Lewis, 1946)  My Name is Julia Ross synopsis: Out of work, Julia Ross (Nina Foch) lives in a boarding house in London. She is behind with her rent by three weeks, and to make matters worse, the man with whom she is in love, Dennis Bruce (Roland Varno) – who used to rent a room in the same lodging house – is currently in Edinburgh preparing to marry another woman. My Name is Julia Ross synopsis: Out of work, Julia Ross (Nina Foch) lives in a boarding house in London. She is behind with her rent by three weeks, and to make matters worse, the man with whom she is in love, Dennis Bruce (Roland Varno) – who used to rent a room in the same lodging house – is currently in Edinburgh preparing to marry another woman.

Seeing an advert for a clerical job, Julia applies for it. She is interviewed by Miss Allison/Sparkes (Anita Sharp-Bolster); the position, Julia is told, is with Mrs Williamson-Hughes (May Whitty) and her son Ralph (George Macready). Julia is offered the position, which is that of a live-in secretary. Julia goes to the Hughes’ house in London but is drugged and transported to their cliff-top house near Beverton, Cornwall. When Julia awakens, she realises she is being held captive by the Hughes family. From her window is a steep drop to the sea below. A maid, Alice (Queenie Leonard), addresses Julia as ‘Mrs Hughes’, and Julia soon learns that she has been abducted and is a stand-in for Ralph’s deceased wife Marion; she was hired because of her physical resemblance to this woman. In fact, Mrs Hughes and Ralph attempt to convince Julia that she is Marion Hughes, whilst also persuading those who visit (such as the local doctor and vicar) that Julia/Marion is suffering from a mental disorder. Meanwhile, Dennis has returned to the lodging house: his wedding has been called off, because his fiancée was disturbed that Dennis kept referring to her as ‘Julia’. He learns from Bertha that Julia applied for a job with the Hughes family and visits their address in London, finding it to be deserted. He vows to track down Julia. In Cornwall, Julia discovered that Marion Hughes died in suspicious circumstances – most likely at the hands of Ralph, who has an unhealthy fascination with knives – and her body was dumped in the sea below the cliffs. She comes to realise that the Hughes family plan to drive her to suicide, so that they may claim her body to be Marion’s. Julia is faced with the task of escaping from the Hughes family, and at the same time Dennis desperately searches for Julia’s location.  So Dark the Night synopsis: Henri Cassin (Steven Geray) is Paris’ most celebrated detective. A quiet, humble man, he is dedicated to his job and has no life beyond it. At the behest of his boss, Commissioner Grande (Gregory Gaye), Cassin is about to take his first holiday in 11 years; for this holiday, Cassin plans to visit the quiet village of St Margot. So Dark the Night synopsis: Henri Cassin (Steven Geray) is Paris’ most celebrated detective. A quiet, humble man, he is dedicated to his job and has no life beyond it. At the behest of his boss, Commissioner Grande (Gregory Gaye), Cassin is about to take his first holiday in 11 years; for this holiday, Cassin plans to visit the quiet village of St Margot.

In St Margot, Cassin encounters Dr Boncourt (Egon Brecher) and the family who own the inn in which Cassin is staying: Pierre Michaud (Eugene Borden), his wife Mama (Ann Codee) and their daughter Nanette (Micheline Cheirel). He also meets their housekeeper, the widow Madame Bridelle (Helen Freeman). Nanette is betrothed to local farmer Leon Achard (Paul Marion), but filled with ambition Mama attempts to push Nanette and Cassin together. Ridden with jealousy, Leon promises to Nanette that ‘If I can’t have you, I’d kill you rather than lose you to anyone else’. Shortly after Nanette calls off her marriage to Leon and becomes engaged to Cassin, Nanette’s corpse is found in a nearby river. She has been strangled. Leon is an obvious suspect, and the local gendarme requests Cassin’s help. They trudge towards Leon’s farm, which is a short distance upstream. There, they expect to arrest Leon but instead find him dead. Examining the clues, Cassin deduces that Leon was killed elsewhere and his body dumped in the pig sty, his death made to look like a suicide, a bottle of acid placed in his hand post-mortem. (Cassin reasons that if Leon had died by drinking the acid, his death spasms would have resulted in the bottle falling from his grasp.) There is a single clue, however: a footprint beneath Leon’s body, left by the killer as he moved the corpse.  Cassin receives a hand-written note declaring that ‘Another will die’. He reasons that the note is the work of a ‘crank’ but nevertheless investigates the letter. Shortly afterwards, Mama is killed in the kitchen of the inn. Cassin accuses Madam Bridelle of committing the murders out of jealousy (‘Madame, a lonesome woman often broods and becomes resentful of the happiness of others. Sometimes she can’t bear that happiness to continue’). However, he soon realises that his accusation is misplaced. Cassin receives a hand-written note declaring that ‘Another will die’. He reasons that the note is the work of a ‘crank’ but nevertheless investigates the letter. Shortly afterwards, Mama is killed in the kitchen of the inn. Cassin accuses Madam Bridelle of committing the murders out of jealousy (‘Madame, a lonesome woman often broods and becomes resentful of the happiness of others. Sometimes she can’t bear that happiness to continue’). However, he soon realises that his accusation is misplaced.

Struggling to identify the possible motive for the murders, and therefore reaching an impasse in his search for the killer, Cassin heads back to Paris and uses the skills of the police sketch artist to assist him, resulting in a traumatic moment of epiphany. Critique: Released consecutively, less than a year apart (My Name is Julia Ross was released in the US in November of 1945, and So Dark the Night in October of 1946), these two films represent the work of director Joseph H Lewis within the genre of the thriller (and during his tenure at Columbia). Lewis is mostly seen as a metteur-en-scene rather than an auteur – a ‘jobbing’ director who was competent at handling material but, other than a handful of pictures and a few moments of eccentricity within his films, didn’t have a definable ‘signature’. Jim Kitses described Lewis as ‘essentially a stylist without a theme’ (Kitses, quoted in Rhodes, 2012: np). Lewis’ most distinctive pictures are perhaps the Dalton Trumbo-scripted Gun Crazy (1950), which consolidated the ‘lovers on the run’ subgenre that would climax with the release of Arthur Penn’s Bonnie & Clyde in 1967, the 1955 film noir The Big Combo and the offbeat Western Terror in a Texas Town (1958), which features a memorable climax in which Sterling Hayden’s Swedish fisherman stands up against hired gun Johnny Crale (blacklisted actor Nedrick Young) using a harpoon instead of a revolver.  Based on the 1941 novel The Woman in Red by Anthony Gilbert, My Name is Julia Ross is the kind of picture that would have been labelled as a ‘woman’s picture’ or melodrama at the time of its release but which has come to be considered an example of what was later termed film noir. Featuring a premise straight out of a Gothic novel – a tortured heroine who takes employment with a family only to find herself imprisoned in their huge house that sits at the top of a cliff in Cornwall – My Name is Julia Ross was considered by Joseph H Lewis to be the film that made his career, despite the fact that he’d shot numerous pictures before it (see Bogdanovich, 1997). The picture was originally released as the second half of a double bill but owing to good notices was promoted to an ‘A’ feature (ibid.). Certainly, the story seems very timely within the context of post-war gender roles: as Sheri Chinen Biesen has suggested, ‘[t]he Gothic heroine seeking employment rather than marriage […] in My Name is Julia Ross reflected the situation of real women at the time’ (Biesen, 2016: 63). This is something inherited directly from the source novel which, written and published during the war, features a jobless English girl who, through desperation and at a time when women were expected to fill the workboots of the men who were fighting overseas, takes a job of work with a treacherous employer. Released after the war ended, Lewis’ film updated this theme for an era in which women were being displaced from the job roles the war effort had pushed them into, and were largely being relegated once again to domestic roles; Julia’s plight at the start of the picture, both single and unemployed, seems within this context metonymic of a broader ‘plight’ of femininity in the period that followed the war. Near the start of the film, she tells her landlady’s daughter, Bertha (Joy Harington), that she plans to apply for a clerical position; ‘Sitting and writing all day, you call that work?!’, Bertha responds sharply. Also, as Gary D Rhodes has argued, Julia is a very unconventional female figure within the context of film noir: ‘one who is independent, not sexually sterile, and yet is not a femme fatale’ (Rhodes, 2012: np). Based on the 1941 novel The Woman in Red by Anthony Gilbert, My Name is Julia Ross is the kind of picture that would have been labelled as a ‘woman’s picture’ or melodrama at the time of its release but which has come to be considered an example of what was later termed film noir. Featuring a premise straight out of a Gothic novel – a tortured heroine who takes employment with a family only to find herself imprisoned in their huge house that sits at the top of a cliff in Cornwall – My Name is Julia Ross was considered by Joseph H Lewis to be the film that made his career, despite the fact that he’d shot numerous pictures before it (see Bogdanovich, 1997). The picture was originally released as the second half of a double bill but owing to good notices was promoted to an ‘A’ feature (ibid.). Certainly, the story seems very timely within the context of post-war gender roles: as Sheri Chinen Biesen has suggested, ‘[t]he Gothic heroine seeking employment rather than marriage […] in My Name is Julia Ross reflected the situation of real women at the time’ (Biesen, 2016: 63). This is something inherited directly from the source novel which, written and published during the war, features a jobless English girl who, through desperation and at a time when women were expected to fill the workboots of the men who were fighting overseas, takes a job of work with a treacherous employer. Released after the war ended, Lewis’ film updated this theme for an era in which women were being displaced from the job roles the war effort had pushed them into, and were largely being relegated once again to domestic roles; Julia’s plight at the start of the picture, both single and unemployed, seems within this context metonymic of a broader ‘plight’ of femininity in the period that followed the war. Near the start of the film, she tells her landlady’s daughter, Bertha (Joy Harington), that she plans to apply for a clerical position; ‘Sitting and writing all day, you call that work?!’, Bertha responds sharply. Also, as Gary D Rhodes has argued, Julia is a very unconventional female figure within the context of film noir: ‘one who is independent, not sexually sterile, and yet is not a femme fatale’ (Rhodes, 2012: np).

Like many examples of Gothic fiction, My Name is Julia Ross juxtaposes the urban and rural spaces. The film begins in London, where Julia is shown via a series of dramatic Dutch angle shots approaching and entering her boarding house. Shot from behind, Julia’s journey takes place during heavy rainfall, symbolic of the hardship Julia experiences in the city whilst looking for employment and struggling to pay her rent. After taking up the offer of employment that is given to her, Julia is abducted and taken to Cornwall, a space in which Julia’s social isolation is replaced by a more physical isolation: Julia finds herself constrained within a locked room in the house of her employer, which itself sits on a cliff edge outside the small village of Beverton. Like many examples of Gothic fiction, My Name is Julia Ross juxtaposes the urban and rural spaces. The film begins in London, where Julia is shown via a series of dramatic Dutch angle shots approaching and entering her boarding house. Shot from behind, Julia’s journey takes place during heavy rainfall, symbolic of the hardship Julia experiences in the city whilst looking for employment and struggling to pay her rent. After taking up the offer of employment that is given to her, Julia is abducted and taken to Cornwall, a space in which Julia’s social isolation is replaced by a more physical isolation: Julia finds herself constrained within a locked room in the house of her employer, which itself sits on a cliff edge outside the small village of Beverton.

When the action moves to Cornwall, and Ralph and his mother attempt to convince Julia that she is in fact Ralph’s murdered wife, My Name is Julia Ross looks towards Patrick Hamilton’s 1938 play Gas Light (filmed by Thorold Dickinson in 1940 and again by George Cukor in 1944) and Andre de Toth’s Dark Waters (1944) whilst anticipating Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious (1946). The conflict between Julia and her older female employer could be said to represent the tension between two generations of women: an older generation of women who had come of age in the inter-war years and who were accustomed to domestic roles, and the younger generation of women who had tasted independence and employment in traditionally ‘male’ roles during the Second World War. (This distinction also cuts across class lines, with the former being representative of the upper middle class and the latter symbolising the working classes.) Within the film’s narrative, the former tries to oppress the latter, to drive Julia mad with the intention that she ultimately commits suicide, thus restoring the ‘traditional’ order. As Sheri Chinen Biesen argues, My Name is Julia Ross ‘express[es] women’s fears about being re-incarcerated within the home, which resonated with women channelled from career back to domesticity after World War II’ (Biesen, op cit.: 63). Meanwhile, the sneering Ralph is played as a disturbed mother’s boy by George Macready, using his knife to tear apart furniture out of boredom. His every move dictated by his mother, Ralph is perhaps a homme fatale, except for the fact that the picture’s real villain is arguably his mother – or rather, Ralph’s relationship with his mother. If Ralph is the ‘dog heavy’ of the picture, Ralph’s mother is the ‘brain heavy’. Ralph has already killed his wife and is in this sense in some ways comparable to Maxim in Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938); Julia’s movement to Cornwall, where she becomes ensnared in a web of treachery and danger, looks back to the paradigms of classic Gothic fiction, such as Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), in which Emily is transplanted to, and trapped within, Montoni’s remote castle. As in those novels, the house in which Julia becomes trapped is a symbol of wealth and status but is ultimately dangerous, being perched on a clifftop; from her window, Julia can see the jagged rocks below and the waves crashing against the base of the cliff. The story later reveals that Ralph and his mother disposed of the corpse of Ralph’s wife by dumping it into the waters below the house. (‘That’s what I like about the sea’, Ralph tells Julia, ‘Never tells its secrets. And it has many, very many secrets’.)  So Dark the Night was Lewis’s second picture for Columbia and though shot on a shoestring budget, the picture is given depth by Lewis’ approach to the material; throughout, the photography plays with depth within the image, framing the action behind or through objects which are carried out of focus by the depth of field. A particularly recurring visual trope within this picture is Lewis’ use of frames within the camera frame: several shots are framed through windows or similar objects, giving the viewer a sense of eavesdropping on the characters and also acting as an almost Brechtian distanciation technique, allowing pieces of action to play out within these frames as if the actors are being filmed on a theatre stage – reminding us of the fabricated nature of what we are watching. So Dark the Night was Lewis’s second picture for Columbia and though shot on a shoestring budget, the picture is given depth by Lewis’ approach to the material; throughout, the photography plays with depth within the image, framing the action behind or through objects which are carried out of focus by the depth of field. A particularly recurring visual trope within this picture is Lewis’ use of frames within the camera frame: several shots are framed through windows or similar objects, giving the viewer a sense of eavesdropping on the characters and also acting as an almost Brechtian distanciation technique, allowing pieces of action to play out within these frames as if the actors are being filmed on a theatre stage – reminding us of the fabricated nature of what we are watching.

In Cassin, So Dark the Night essays the role of a detective who, according to the dialogue, is so ‘single-tracked’ in his work that he ‘even seems stupid and sluggish’. This is how Commissioner Grande, played by Gregory Gaye, describes Cassin in the film’s early sequences. Grande also states that Cassin ‘would go without sleep endlessly, day after day, when he’s engaged in a chase. He’s the most endless machine I have ever known’. Cassin’s lack of social graces is conveyed when he reaches St Margot and is introduced to Madam Bridelle; he is told that she is a widow and comments, ‘That’s really good of you’ before correcting himself and saying, in a different tone, ‘I mean, how sad’. In some ways, at least in the early scenes of the film, Cassin could be taken as a precursor of Peter Falk’s Columbo, a similarly driven detective whose humble manner belies a razor sharp mind. ‘Just relax and enjoy life for a change’, Grande tells Cassin as Cassin prepares to visit St Margot; as the narrative progresses, the profound irony within his words becomes increasingly apparently.  So Dark the Night juxtaposes the city with the countryside, the sophisticated with the naive. Word of Cassin’s successes has spread to St Margot; Nanette is introduced by her mother as ‘a great admirer of your work’. Mama’s ambitions for her daughter, to marry for status over love, recall Mildred’s relationship with her daughter Veda in James M Cain’s 1941 novel Mildred Pierce. ‘Love has its place’, Mama tells Pierre, ‘but it puts no butter on the bread. My daughter is going to have all the things I missed. And is she uses her wits, she can marry Monsieur Cassin’. When Nanette calls off her impending marriage to Leon and becomes engaged to Cassin, Leon sharply highlights the real reason for Nanette’s change of heart, which lies in Mama’s aspirations for her daughter: ‘I don’t blame you’, Leon tells Nanette, ‘It’s your mother. She never liked me because I am poor, and this detective is rich and famous’. So Dark the Night juxtaposes the city with the countryside, the sophisticated with the naive. Word of Cassin’s successes has spread to St Margot; Nanette is introduced by her mother as ‘a great admirer of your work’. Mama’s ambitions for her daughter, to marry for status over love, recall Mildred’s relationship with her daughter Veda in James M Cain’s 1941 novel Mildred Pierce. ‘Love has its place’, Mama tells Pierre, ‘but it puts no butter on the bread. My daughter is going to have all the things I missed. And is she uses her wits, she can marry Monsieur Cassin’. When Nanette calls off her impending marriage to Leon and becomes engaged to Cassin, Leon sharply highlights the real reason for Nanette’s change of heart, which lies in Mama’s aspirations for her daughter: ‘I don’t blame you’, Leon tells Nanette, ‘It’s your mother. She never liked me because I am poor, and this detective is rich and famous’.

As Cassin investigates the murders of Nanette and Leon, he reasons that the key to solving them lies in identifying the killer’s motive. However, there is no apparent reason for the killings: ‘Was it revenge?’, he reasons, ‘In revenge for what? Was it for gain? But who could gain by it?’ The motiveless nature of the killings, and the killer’s taunting of Cassin via a series of notes (‘Another will die’, ‘You will die next’, etc), might remind viewers of the paradigms of later examples of the Italian-style thriller (thrilling all’italiana/giallo all’italiana) such as Dario Argento’s L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, 1970). Like My Name is Julia Ross, So Dark the Night also nods towards the conventions of Gothic fiction – in this case, through its use of a doppelganger motif. The revelation of the killer’s identity offers some woolly but very much of-its-time psychologising of the kind that Hitchcock parodied in the closing sequence of Psycho (1960).

Video

My Name is Julia Ross has a running time of 65:02 mins. So Dark the Night has a running time of 70:16 mins. My Name is Julia Ross has a running time of 65:02 mins. So Dark the Night has a running time of 70:16 mins.

Both films are presented in 1080p using the AVC codec. So Dark the Night fills a little over 20Gb on its Blu-ray disc; My Name is Julia Ross fills a little over 18Gb of space on its disc. Both films were shot on 35mm monochrome stock, and are presented in their original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. My Name is Julia Ross opens with some bravura Dutch angle shots, but the photography becomes more staid after this, though here, as in So Dark the Night, Lewis shows a tendency to frame action behind objects which are carried out of focus by shallow depth of field; this gives a sense of depth to the photography and also adds a voyeuristic frisson to the proceedings. In So Dark the Night, Lewis amplifies this by shooting a number of scenes through doorframes or windows, giving a sense of looking in from the outside and also subtly reminding viewers of the artifice of what they are watching. The labyrinthine visuals in So Dark the Night mirror the complexities of the plot.  My Name is Julia Ross looks very good on this Blu-ray presentation. There are some noticeable density fluctuations in the emulsions of the source material but nothing to write home about. Detail is crisp and rich. The texture of rain drops in the opening sequence is discernible, for example. Contrast levels are nicely-balanced. Rich and defined midtones are accompanied by a good fall-off into the toe. Highlights are event-balanced too. The encoded to disc is pleasing, and the whole presentation has a pleasingly filmlike texture. My Name is Julia Ross looks very good on this Blu-ray presentation. There are some noticeable density fluctuations in the emulsions of the source material but nothing to write home about. Detail is crisp and rich. The texture of rain drops in the opening sequence is discernible, for example. Contrast levels are nicely-balanced. Rich and defined midtones are accompanied by a good fall-off into the toe. Highlights are event-balanced too. The encoded to disc is pleasing, and the whole presentation has a pleasingly filmlike texture.

So Dark the Night opens with a funky looking optically-printed titles sequence which quickly settles into a very good presentation. The staging in depth is carried excellently in this presentation, a sense of depth being retained within the digital transfer and a very pleasing level of fine detail being present throughout. Contrast levels are very good, with rich midtones and deep blacks. As with the other picture, So Dark the Night gets a pleasing encode to disc which retains the structure of 35mm film. Full-sized screengrabs from both films are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

Both films are presented via LPCM 2.0 mono tracks. These have good depth and range, and dialogue is discernible throughout. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included on both discs, and these are easy to read and accurate in transcribing the films’ dialogue. The dialogue of So Dark the Night is mostly in English though characters code switch into French for exclamatory remarks – giving the impression of taboo speech.

Extras

My Name is Julia Ross My Name is Julia Ross

The disc includes: - An audio commentary by Alan K Rode. Rode, the author of books about Michael Curtiz and Charles McGraw, discusses the production history of My Name is Julia Ross and the picture’s place in the careers of Lewis and Nina Foche. Rode reflects on Lewis’ career and how Lewis reinvented himself in the era of auteurist criticism, in particular. - ‘Identity Crisis: Joseph H Lewis at Columbia’ (21:35). Nora Fiore, who blogs about classical Hollywood cinema under the nom-de-plume The Nitrate Diva, discusses the film’s representation of women and how this connected with the post-war era. She reflects on Lewis’ career and how he worked his way up to being a film director, and she talks about the evolution of Lewis’ approach to filmmaking – considering the ‘visual flair’ that Lewis exhibited within his pictures. - Trailer (1:37).  So Dark the Night So Dark the Night

The disc includes: - An audio commentary by Glenn Kenny and Farran Smith Nehme. Critics Kenny and Nehme provide an evenly-balanced discussion of So Dark the Night that considers the film’s cast and crew. They reflect on Lewis’ approach to filmmaking and his nickname ‘Wagon Wheel Joe’, which he acquired by displaying a tendency to shoot through the spokes of wagon wheels during his time making ‘poverty row’ Westerns. They discuss some of the ‘dismissive’ reviews that So Dark the Night received at the time of it first release. - ‘A Dark Place: Joseph H Lewis at Columbia’ (20:07). Imogen Sara Smith, whose book In a Lonely Place focuses on films noir set in non-urban spaces, considers So Dark the Night’s relationship with the paradigms of noir. She considers the extent to which the picture was something of a personal project for Lewis, and reflects on the variance within Lewis’ noir films. She also talks about Columbia’s work as a studio and this film’s place within Columbia’s body of work. - Trailer (1:36).

Overall

Joseph H Lewis had made almost two dozen films before directing My Name is Julia Ross and So Dark the Night, but nevertheless these two pictures – made during Lewis’ tenure at Columbia – show Lewis’ style as a filmmaker emerging; though it’s debatable as to whether or not Lewis could be considered an auteur in the true sense, certainly these two films act as a bridge between Lewis’ earlier, fairly anonymous pictures and his later films – such as The Big Combo, Gun Crazy and The Undercover Man (1949). Joseph H Lewis had made almost two dozen films before directing My Name is Julia Ross and So Dark the Night, but nevertheless these two pictures – made during Lewis’ tenure at Columbia – show Lewis’ style as a filmmaker emerging; though it’s debatable as to whether or not Lewis could be considered an auteur in the true sense, certainly these two films act as a bridge between Lewis’ earlier, fairly anonymous pictures and his later films – such as The Big Combo, Gun Crazy and The Undercover Man (1949).

My Name is Julia Ross is an efficient thriller, managing to compact many narrative events into its short running time. The film contains many Gothic elements, and in particular it looks towards Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca and some classic Gothic novels for its inspiration. A suitably paranoid tone is engendered, especially once the story moves to Cornwall. So Dark the Night is a lean and ultimately quite bleak film. It’s easy to see why critics of the day were so dismissive of this picture, given the manner in which the story resolves itself. The film’s emphasis on a particularly twisted kind of psychology and its lack of consistent or acceptable motivation for the killings seems to anticipate some of the European thrillers (particularly Italian-style thrillers) of the 1960s and 1970s. These elements may have alienated critics of the day but are perhaps more acceptable to audiences today. Both films are very stylishly-shot, Lewis making strong use of objects within the mise-en-scène to create a sense of depth within the photography, and also making fascinating use of frames-within-the frame, mirrors and windows to visualise the moral complexities of the films’ plots. Arrow’s Blu-ray releases of both films contain excellent presentations of the main features, and both discs contain some good contextual material. The interview with Imogen Sara Smith on the So Dark the Night disc, in particular, is on-point in terms of its engagement with Lewis’ work as a director. References: Biesen, Sheri Chinen, 2016: ‘Haunting Landscapes in “Female Gothic” Thriller Films: From Alfred Hitchcock to Orson Welles’. In: Yang, Sharon Rose & Healey, Kathleen (eds), 2016: Gothic Landscapes: Changing Eras, Changing Cultures, Changing Anxieties. London: Palgrave Macmillan: 47-70 Bogdanovich, Peter, 1997: Who the Devil Made It? Conversations with Legendary Film Directors. Ballantine Books Rhodes, Gary D, 2012: The Films of Joseph H Lewis. Wayne State University Press My Name is Julia Ross:

So Dark the Night:

|

|||||

|