|

|

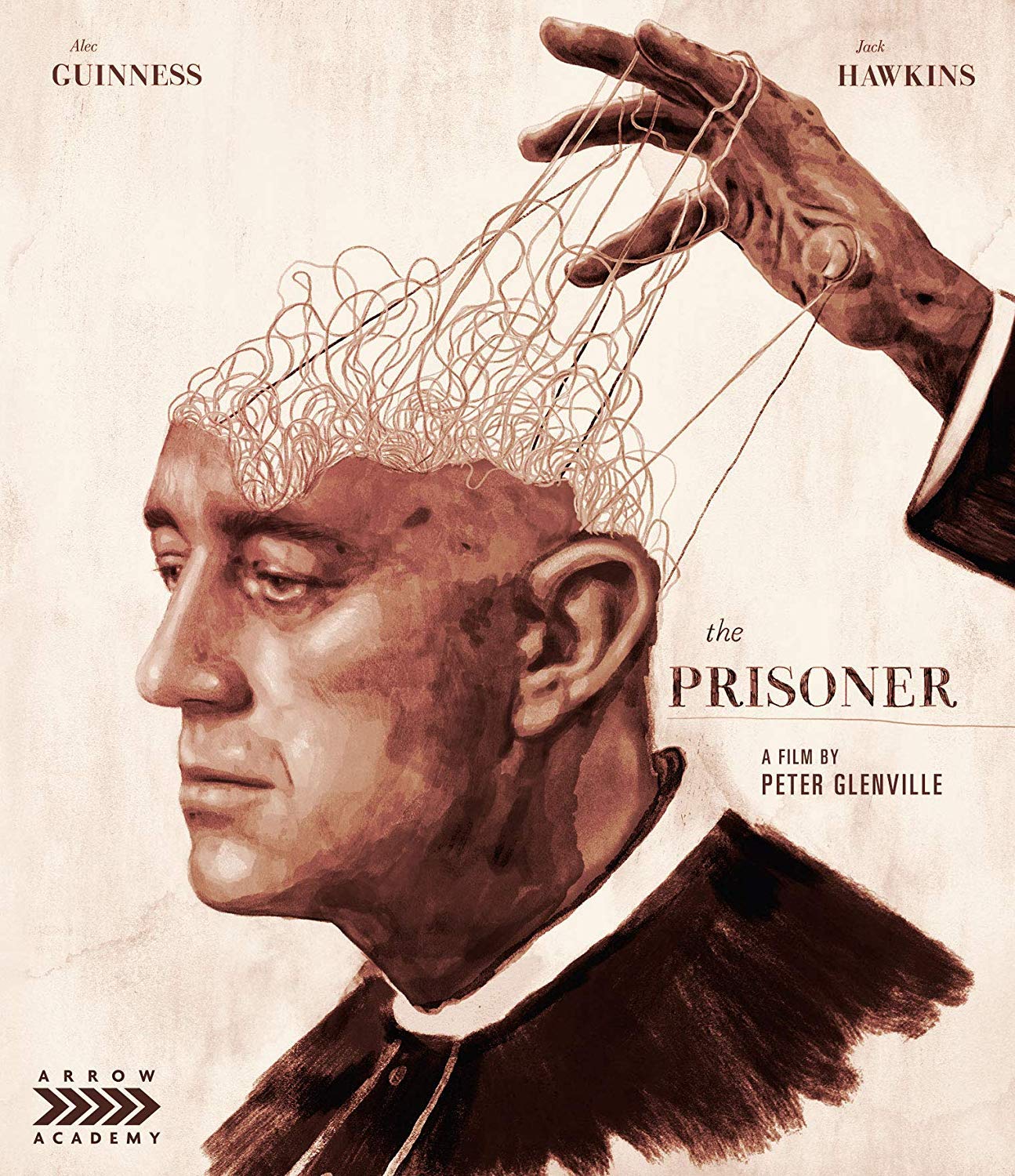

Prisoner (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (22nd March 2019). |

|

The Film

The Prisoner (Peter Glenville, 1955) – a review of Arrow Academy’s new Blu-ray release. The Prisoner (Peter Glenville, 1955) – a review of Arrow Academy’s new Blu-ray release.

Synopsis: In an unnamed country once wracked by Nazi invaders and now under Communist rule, a beloved Cardinal (Alec Guinness) is arrested immediately after he has delivered a religious service. The Cardinal is accused of treason and is interrogated by a former ally (Jack Hawkins). Both the Cardinal and his interrogator were members of the Resistance, and the Cardinal became something of a hero during the Nazi regime when, captured by the Gestapo, he resisted their torture of him. The Cardinal is perplexed at the accusation of treason, but his interrogator reminds the Cardinal that the Catholic church is ‘a religion which provides an organisation outside the state’, and this makes the Cardinal ‘more dangerous than any politician’. The interrogator provides the Cardinal with a pre-written confession, telling him that all he has to do is sign it. However, the Cardinal refuses and is subjected to psychological torture: placed in a cell with limited light, he is prevented from sleeping and driven to physical exhaustion. (‘It’s your mind we want’, the interrogator tells the Cardinal.) The Cardinal becomes the centre of a show trial; at each stage, the Cardinal points out with severe logic the manner in which the ‘evidence’ against him has been doctored. The Cardinal is presented with his elderly mother, who has been anaesthetised, and is threatened with the suggestion that if the Cardinal does not comply, his mother will be sent to a research hospital. However, the Cardinal still refuses to co-operate with his interrogator, confessing that he does not love his mother. This revelation provokes disgust in the interrogator, who comes to the realisation that the key to ‘breaking’ the Cardinal lies in the Cardinal’s desire to escape from the poverty of his childhood.  Critique: Based on the play by Bridget Boland and adapted for the screen by Boland herself, Peter Glenville’s The Prisoner (1955) was rooted in the persecution of Cardinal József Mindszenty in post-war Hungary. Mindszenty had been imprisoned by the fascist Arrow Cross Party during the Second World War, and after the war Mindszenty’s anti-Communist stance led to him being once again captured and tortured – this time, by those on the other side of the political spectrum. In 1949, Mindszenty was tortured into confessing to treason and subsequently given a life sentence in a show trial that was widely condemned on the international stage. He was released in 1956, following the Hungarian Revolution before being granted political asylum at the US embassy in Budapest, where Mindszenty lived for the next fifteen years, unable to step foot outside the embassy grounds. In 1971, he was finally granted permission by the Hungarian government to leave the country and went to live the remainder of his life in Austria, where he eventually died (in 1975). The persecution of Mindszenty had previously been dramatised in the 1950 picture Guilty of Treason (directed by Felix E Feist) and was more heavily fictionalised in a two-part story from the first series of Mission: Impossible, ‘Old Man Out’ (CBS, 1966). Critique: Based on the play by Bridget Boland and adapted for the screen by Boland herself, Peter Glenville’s The Prisoner (1955) was rooted in the persecution of Cardinal József Mindszenty in post-war Hungary. Mindszenty had been imprisoned by the fascist Arrow Cross Party during the Second World War, and after the war Mindszenty’s anti-Communist stance led to him being once again captured and tortured – this time, by those on the other side of the political spectrum. In 1949, Mindszenty was tortured into confessing to treason and subsequently given a life sentence in a show trial that was widely condemned on the international stage. He was released in 1956, following the Hungarian Revolution before being granted political asylum at the US embassy in Budapest, where Mindszenty lived for the next fifteen years, unable to step foot outside the embassy grounds. In 1971, he was finally granted permission by the Hungarian government to leave the country and went to live the remainder of his life in Austria, where he eventually died (in 1975). The persecution of Mindszenty had previously been dramatised in the 1950 picture Guilty of Treason (directed by Felix E Feist) and was more heavily fictionalised in a two-part story from the first series of Mission: Impossible, ‘Old Man Out’ (CBS, 1966).

Mindszenty’s persecution was seen as highly symbolic of the cultural shifts that took place after the Second World War, Mindszenty’s treatment by both fascist and communist elements having equivalence. Some of the key personnel involved in making The Prisoner – Bridget Boland, Peter Glenville and Alec Guinness – were Catholics and very attuned to the anti-Catholic sentiment within Mindszenty’s torture at the hands of his communist captors. When Columbia suggested the film be stripped of its references to Catholicism, Guinness and the others told them this would be impossible: ‘without its Catholicism it [the script] would be meaningless’, Guinness would reflect in his diaries (quoted in Read, 2003: 280).  In contrast with Guilty of Treason, The Prisoner offers a more abstracted, intellectual approach to the same basic material. The conflict within The Prisoner takes place largely within the conversations between captor and interrogator, the content of their dialogue becoming metonymic of ideological conflicts on a much broader scale. The two men spar verbally, attacking one another’s logic and attempting to defeat one another psychologically. At one point, rumour has it, producer Sidney Box considered casting Guinness as both the captured Cardinal and his interrogator; Guinness put the kibosh on this idea, describing it as ‘outrageous’ (see Read, 2003: 280). Prior to making this picture, Glenville had directed the stage version of Boland’s play and Guinness had also acted in it. Jack Hawkins’ role in the picture, as the interrogator, was very much against the ‘type’ that Hawkins had cultivated in previous roles, as heroic figures of authority. In contrast with Guilty of Treason, The Prisoner offers a more abstracted, intellectual approach to the same basic material. The conflict within The Prisoner takes place largely within the conversations between captor and interrogator, the content of their dialogue becoming metonymic of ideological conflicts on a much broader scale. The two men spar verbally, attacking one another’s logic and attempting to defeat one another psychologically. At one point, rumour has it, producer Sidney Box considered casting Guinness as both the captured Cardinal and his interrogator; Guinness put the kibosh on this idea, describing it as ‘outrageous’ (see Read, 2003: 280). Prior to making this picture, Glenville had directed the stage version of Boland’s play and Guinness had also acted in it. Jack Hawkins’ role in the picture, as the interrogator, was very much against the ‘type’ that Hawkins had cultivated in previous roles, as heroic figures of authority.

Certainly, the script for The Prisoner has a ‘stagey’ feel to it, the bulk of the picture taking place in two-hander scenes between Guinness and Hawkins, or in Guinness’ cell. Glenville opts to make this content more cinematic, however, by interspersing into this material some interesting use of chiaroscuro lighting and obtuse camera angles, including a number of overhead shots that make the participants – both captive and interrogator – seem small and powerless, reinforcing their roles as cogs in the machine of ideology.  The Cardinal is depicted as a tolerant patriarch who is benevolent even towards the guard who, upon the Cardinal’s arrest, mocks the Cardinal’s finery and steals his cigarettes. (‘That’s where the money goes, eh?’, the guard mocks the Cardinal whilst removing his valuables – a watch, a cigarette box, rings and a rosary – ‘You’ve no need for larceny, have you? Petty larceny, that is. And if you do rob your own poor boxes, who’s to know?’) In the midst of his captivity, he prays for the interrogator and calmly acknowledges the doctor’s role in his persecution, mitigating this with an acknowledgment that the doctor has previously done charitable works and must have been forced by circumstance into collaborating with the regime. (‘I know. Things happen to us’, the Cardinal observes sadly.) Though this regime is clearly Communist in nature, it persecutes a man – the Cardinal – who the narrative reveals to be from an impoverished background, raised near a fish market by a mother who, it is suggested, prostituted herself in order to feed her family. Meanwhile, the Cardinal’s interrogator, the representative of this regime, is shown to be from a privileged background. This conflict, in terms of the backgrounds of the two main characters, points at the hypocrisy of the Communist regime. The Cardinal is an intellectual, civilised man who maintains his composure throughout most of the narrative. However, a brief scene suggests an internal conflict: when, after having endured what may be months of solitary confinement, the Cardinal ‘snaps’ and in a fit of rage throws to the floor the meagre furniture of his cell (a chair and a desk), demonstrating a physicality that has been hitherto concealed, he almost immediately corrects himself and reseats the furniture. This small gesture suggests that the Cardinal has buried his physicality (indexical of his background within the working class, given that cinema and literature tend to depict the working classes as a group ruled by physicality and instinct) within a carefully managed and cultivated exterior presence (symbolic of his transition from the working class to his role within the Catholic church). In this sense, The Prisoner emphasises Guinness’ strengths as an actor in roles that suggest repression and emotional/physical reservation. However, the Cardinal is driven by pride, rooted in a desire to escape from his background; he was motivated to deliver incredible sermons by his own personal desire to avoid mediocrity more than by a need to enrich the lives of those listening to him. The Cardinal is depicted as a tolerant patriarch who is benevolent even towards the guard who, upon the Cardinal’s arrest, mocks the Cardinal’s finery and steals his cigarettes. (‘That’s where the money goes, eh?’, the guard mocks the Cardinal whilst removing his valuables – a watch, a cigarette box, rings and a rosary – ‘You’ve no need for larceny, have you? Petty larceny, that is. And if you do rob your own poor boxes, who’s to know?’) In the midst of his captivity, he prays for the interrogator and calmly acknowledges the doctor’s role in his persecution, mitigating this with an acknowledgment that the doctor has previously done charitable works and must have been forced by circumstance into collaborating with the regime. (‘I know. Things happen to us’, the Cardinal observes sadly.) Though this regime is clearly Communist in nature, it persecutes a man – the Cardinal – who the narrative reveals to be from an impoverished background, raised near a fish market by a mother who, it is suggested, prostituted herself in order to feed her family. Meanwhile, the Cardinal’s interrogator, the representative of this regime, is shown to be from a privileged background. This conflict, in terms of the backgrounds of the two main characters, points at the hypocrisy of the Communist regime. The Cardinal is an intellectual, civilised man who maintains his composure throughout most of the narrative. However, a brief scene suggests an internal conflict: when, after having endured what may be months of solitary confinement, the Cardinal ‘snaps’ and in a fit of rage throws to the floor the meagre furniture of his cell (a chair and a desk), demonstrating a physicality that has been hitherto concealed, he almost immediately corrects himself and reseats the furniture. This small gesture suggests that the Cardinal has buried his physicality (indexical of his background within the working class, given that cinema and literature tend to depict the working classes as a group ruled by physicality and instinct) within a carefully managed and cultivated exterior presence (symbolic of his transition from the working class to his role within the Catholic church). In this sense, The Prisoner emphasises Guinness’ strengths as an actor in roles that suggest repression and emotional/physical reservation. However, the Cardinal is driven by pride, rooted in a desire to escape from his background; he was motivated to deliver incredible sermons by his own personal desire to avoid mediocrity more than by a need to enrich the lives of those listening to him.

An equivalence is drawn between the Cardinal’s treatment at the hands of the Gestapo and his ‘handling’ by the post-war Communist authorities, the Cardinal reminding his interrogator that whilst in the captivity of the Gestapo he did not surrender to their methods of torture; the Cardinal also reminds his interrogator that faced with fascism, the pair were on the same side, that of the Resistance, whereas under the post-war Communist regime they have been set against one another, the Communist ideology dividing what was once united. ‘At least one was on the same side as all one’s fellow countrymen’, the Cardinal tells his interrogator when the latter reminds the Cardinal of his role as a ‘hero to me in the Resistance, as you were to all of us’.

Video

Filling 26Gb on the Blu-ray disc, The Prisoner is presented in 1080p using the AVC codec. The film runs for 93:47 mins and would seem to be uncut. For this new Blu-ray release of the film, Arrow Academy were presented with a digital master that was provided by Sony. The Prisoner is presented in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio, which is most likely commensurate with its original cinema exhibition ratio though in a number of scenes, the framing along the vertical axis seems very tight. Filling 26Gb on the Blu-ray disc, The Prisoner is presented in 1080p using the AVC codec. The film runs for 93:47 mins and would seem to be uncut. For this new Blu-ray release of the film, Arrow Academy were presented with a digital master that was provided by Sony. The Prisoner is presented in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio, which is most likely commensurate with its original cinema exhibition ratio though in a number of scenes, the framing along the vertical axis seems very tight.

Shot in monochrome on 35mm, The Prisoner features some interesting photography that undercuts any ‘staginess’ within the script. The film features some wonderfully expressionistic shots, combining some big, elaborate sets, obtuse camera angles and strong chiaroscuro lighting. Detail is pleasing throughout the presentation, the image having a strong sense of definition and clarity. That said, some scenes are much richer in detail than others, and there’s a slight inconsistency within the presentation vis-à-vis clarity and detail. Some minor damage is present within the presentation – mostly consisting of small white flecks and specks, suggestive of dust and debris on the negative. Highlights are even and balanced and gradation into the blacks is subtle. The encode to disc is pleasing, the presentation retaining the structure of 35mm film. Some full-size screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 track, in English. This is rich and problem-free. Dialogue is audible throughout. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included, and these are easy to read and accurate in transcribing the film’s dialogue.

Extras

The disc includes: - ‘Interrogating Guinness’ (23:49). Critic Neil Sinyard reflects on the impact and legacy of The Prisoner, discussing the controversies surrounding the film and discussing the circumstances surrounding its production. Sinyard examines the input of Guinness, Glenville and Boland, situating The Prisoner within Boland’s work’s focus on issues of belief. - ‘Selected Scene Commentary’ (15:02). Critic Philip Kemp provides an analysis of four key scenes from The Prisoner, offering some detailed reflection on the importance of these scenes for the overall ‘meaning’ of the picture.

Overall

Though obviously based in the persecution of Mindszenty, The Prisoner also has some interesting parallels with the persecution of Sir Thomas More and, in particular, Robert Bolt’s play about More, A Man for All Seasons (1960), which emphasised More’s unbowing commitment to his beliefs; certainly, Mindszenty has sometimes been compared with More (see Mindszenty Report, 2015). Glenville’s film adaptation of Boland’s play is an interesting picture, and Glenville makes some strong attempts to mitigate the inherent ‘staginess’ of the material through interesting use of the camera, sets and lighting – offering an almost expressionistic visual interpretation of the material. The picture is also aided by strong central performances from both Guiness and Hawkins. However, on the other hand Boland’s script is sometimes ideologically incoherent and arguably has a tendency to feel overly didactic. Though obviously based in the persecution of Mindszenty, The Prisoner also has some interesting parallels with the persecution of Sir Thomas More and, in particular, Robert Bolt’s play about More, A Man for All Seasons (1960), which emphasised More’s unbowing commitment to his beliefs; certainly, Mindszenty has sometimes been compared with More (see Mindszenty Report, 2015). Glenville’s film adaptation of Boland’s play is an interesting picture, and Glenville makes some strong attempts to mitigate the inherent ‘staginess’ of the material through interesting use of the camera, sets and lighting – offering an almost expressionistic visual interpretation of the material. The picture is also aided by strong central performances from both Guiness and Hawkins. However, on the other hand Boland’s script is sometimes ideologically incoherent and arguably has a tendency to feel overly didactic.

Arrow Academy’s new Blu-ray release of The Prisoner offers a pleasingly filmlike high definition presentation of the main feature, albeit one which exhibits some noticeable (though utterly organic) damage, and is accompanied by two brief but thoughtful ‘extras’. References: Mindszenty Report, 2015: ‘Cardinal Mindszenty: A Man for All Seasons’. Catholic Journal: Reflections on Faith & Culture. [Online.] https://www.catholicjournal.us/2015/06/17/cardinal-mindszenty-a-man-for-all-seasons/ Read, Piers Paul, 2003: Alec Guinness: The Authorised Biography. London: Simon & Schuster Please click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|