|

|

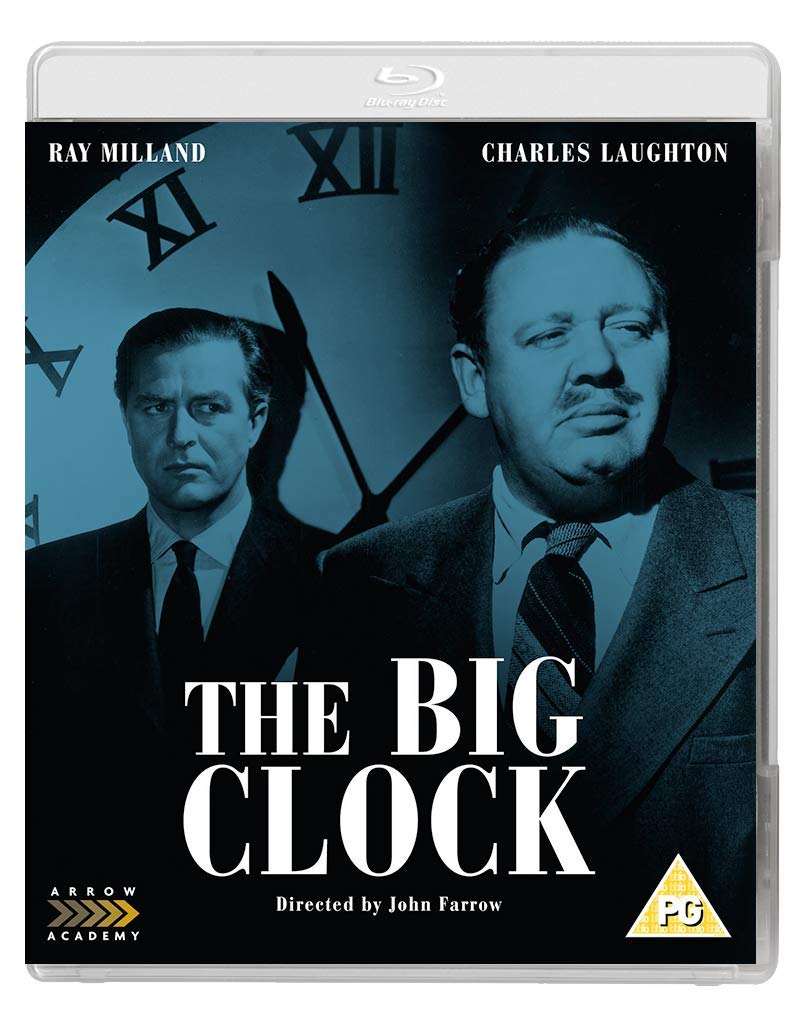

Big Clock (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (25th May 2019). |

|

The Film

The Big Clock (John Farrow, 1948) The Big Clock (John Farrow, 1948)

Synopsis: Hiding in the mechanism of the huge clock that dominates the lobby of the Janoth Corporation building, George Stroud (Ray Milland) reflects on the 36 hours that led him to his current predicament. Stroud is the editor of Crimeways, one of the Janoth Corporation's many publications. Known for finding clues that the police have overlooked and finding key persons involved in criminal cases, thus giving Crimeways circulation-grabbing exclusives, Stroud is a key member of Janoth Corporations. However, Stroud is deeply unhappy: the head of Janoth Corporation, Earl Janoth (Charles Laughton) is a particularly unpleasant man, known for making outrageous demands on his staff. Janoth is also involved in a strange relationship with a woman, Pauline York (Rita Johnson). Janoth and Pauline seem to be lovers, but Janoth has also been paying off Pauline through Janoth’s right-hand man Steve Hagen (George Macready). Stroud has been planning to take his first holiday since starting his employ with Janoth Corporation a number of years previously; in fact, Stroud cut his honeymoon short in order to take the job as editor of Crimeways, much to the chagrin of Stroud’s patient wife Georgette (Maureen O’Sullivan). However, Janoth has other ideas and presses Stroud to cancel his holiday – or Janoth will ensure Stroud loses his job at the Janoth Corporation and is blacklisted from working on any other magazines in the future. Stroud encounters Pauline, who offers Stroud the chance to get one up on Janoth. (‘I know enough about Mr Janoth to make him change his mind about both of us’, Pauline promises Stroud.) Pauline suggests she and Stroud should share information about Janoth and blackmail him with it. When Stroud’s meeting with Pauline overruns and, after calling home, he discovers from his maid that Georgette has already left for the holiday with their young son, George Stroud, Jr, Stroud spends the night on the town with Pauline. A slightly loaded Stroud buys a painting by the eccentric local artist Mrs Patterson (Elsa Lanchester); and at Burt’s Place, a bar Stroud frequents and which is run by the friendly Burt (Frank Orth), Stroud persuades Burt to part with a sundial.  Drunk, Stroud comes to in Pauline’s apartment. Janoth is on his way up and Pauline ushers Stroud out. Stroud watches Janoth arrive. Inside Pauline’s apartment, Janoth and Pauline have an argument, and Janoth uses the sundial from Burt’s Place, which Stroud has left with Pauline, as a bludgeon, killing Pauline. After the murder, Janoth demands that his friend and subordinate, Steve, help him cover it up. However, Janoth knows that somebody saw him leaving Pauline’s apartment and, not knowing that it was Stroud, seeks Stroud’s help in tracking down this potential witness. Stroud is faced with covering his own tracks whilst also finding a way to ensure that Janoth pays for his crime; all the while, the hands of the big clock tick away every second. Drunk, Stroud comes to in Pauline’s apartment. Janoth is on his way up and Pauline ushers Stroud out. Stroud watches Janoth arrive. Inside Pauline’s apartment, Janoth and Pauline have an argument, and Janoth uses the sundial from Burt’s Place, which Stroud has left with Pauline, as a bludgeon, killing Pauline. After the murder, Janoth demands that his friend and subordinate, Steve, help him cover it up. However, Janoth knows that somebody saw him leaving Pauline’s apartment and, not knowing that it was Stroud, seeks Stroud’s help in tracking down this potential witness. Stroud is faced with covering his own tracks whilst also finding a way to ensure that Janoth pays for his crime; all the while, the hands of the big clock tick away every second.

Critique: Based on the 1946 novel by Kenneth Fearing, The Big Clock is actually one of three very different film adaptations of Fearing’s book: the others are Alain Corneau’s very French policier picture Police Python 357, starring Yves Montand; and Roger Donaldson’s 1987 neo-noir film No Way Out. Unlike Farrow’s 1948 film, those two later pictures took some distinct liberties with Fearing’s novel, which had two major sources of inspiration. One of these was Sam Fuller’s then-recently published novel The Dark Page (1944), in which Carl Chapman, the editor of a newspaper, commits a murder and finds himself under investigation by the newspaper’s top crime reporter. Faced with the prospect of the crime he has committed being uncovered, Chapman nevertheless discovers that the coverage of the murder is helping to increase the circulation of his newspaper, and therefore must encourage his top crime reporter to keep digging into the story. Rich in Fuller’s own experiences in the world of journalism, The Dark Page is a typically Fuller-esque journey into liminal morality. The other source of inspiration for The Big Clock was the 1943 murder of wealthy heiress Patricia Lonergan by her husband, which was complicated by the fact that Patricia Lonergan had spent the evening before her murder on a ‘crawl’ of trendy nightclubs in the company of an interior decorator, Mario Gabellini – with whom Lonergan publicly quarrelled after she had danced with an officer in the marine corps, Peter Elser. Fearing took from these two sources of inspiration a focus on the milieu of crime journalism and the importance of improving one’s circulation (and the notion of an editor of such a publication and his subordinate being at odds), and from the Lonergan case Fearing seems to have been inspired by Lonergan’s relationship with Gabellini, whose ‘nightclub crawl’ with the victim was a distinct red herring to the police. Fearing also seems to have taken from the Lonergan case the primary motive for the crime: Patricia Lonergan and her husband argued over previous sexual relationships, with the press reports intimating that Patricia suggested her husband was secretly gay and this caused him to commit the murder of his wife.  Alan M Wald has suggested another source of inspiration for Fearing’s novel: Fearing’s employment, for six months in 1942, with Henry Luce (Wald, 2012: 39). Founding Time magazine with Britton Hadden in 1923, Luce found himself frozen out when Hadden died in 1928: Hadden’s shares within Time were left to Hadden’s family, intentionally ‘out of Luce’s reach’ (ibid.). However, Luce subsequently ‘managed to gain control of these crucial stocks, then erased Hadden’s name from the masthead of Time and the official memory of the company. Luce even managed to secure Hadden’s papers and house them at Time, Inc., inaccessible to the public’ (ibid.). Afterwards, Luce founded Fortune and Life (in 1930 and 1936, respectively). As Wald suggests, Fearing seems to have used the relationship between Hadden and Luce as inspiration for his depiction of the Janoth-Haden relationship in The Big Clock (ibid.). Alan M Wald has suggested another source of inspiration for Fearing’s novel: Fearing’s employment, for six months in 1942, with Henry Luce (Wald, 2012: 39). Founding Time magazine with Britton Hadden in 1923, Luce found himself frozen out when Hadden died in 1928: Hadden’s shares within Time were left to Hadden’s family, intentionally ‘out of Luce’s reach’ (ibid.). However, Luce subsequently ‘managed to gain control of these crucial stocks, then erased Hadden’s name from the masthead of Time and the official memory of the company. Luce even managed to secure Hadden’s papers and house them at Time, Inc., inaccessible to the public’ (ibid.). Afterwards, Luce founded Fortune and Life (in 1930 and 1936, respectively). As Wald suggests, Fearing seems to have used the relationship between Hadden and Luce as inspiration for his depiction of the Janoth-Haden relationship in The Big Clock (ibid.).

The Big Clock was the second collaboration between director John Farrow and actor Ray Milland: Farrow and Milland had previously made California (1947) together and would subsequently collaborate on Alias Nick Beal (1949) and Copper Canyon (1950). Farrow reputedly had a reputation as a director who was difficult to work with, though it seems that Farrow was frustrated by the script-learning abilities (or lack thereof) of many of the studio contract players who acted in his pictures. In Milland, he found an actor who was adept at learning his lines, leading to a productive relationship between director and star that spanned four pictures. In the film’s opening sequence, Milland embodies the prototypical film noir anti-hero, skulking through the Janoth Corporation building at night, evading guards. He also narrates, in the first person and suspense-building present tense: ‘More guards [….] And they said “shoot to kill”’, he begins, ‘How’d I get into this rat race, anyway? I’m no criminal. What happened? When did it all start? Just 36 hours ago, I was down there, crossing that lobby on my way to work, minding my own business [….] 36 hours ago, I was a decent, respectable, law-abiding citizen with a wife and a kid and a big job’. As Stroud is shown concealed in the titular big clock, the camera tilts down – and in doing so, takes us from the diegetic present to the past, seamlessly bringing us into the lobby of the Janoth Corporation 36 hours earlier.  The Big Clock offers a critical perspective on the corporatisation of life in the Twentieth Century, Janoth being depicted as an absurdly powerful man within an absurdly powerful company. (‘Isn’t it a pity that the wrong people always have money’, a character observes at one point.) As the film opens, the Janoth Corporation is facing the squeeze from new media outlets: in the boardroom, Janoth reminds his employees that the company is facing ‘dynamic competitors: radio, television, newsreels. And we must anticipate trends before they are trends. We are, in effect, clairvoyants’. Laughton’s obesity, used here as a signifier of self-indulgence, is accompanied by a sneering, haughty manner. He has installed covert surveillance equipment in the offices of his employees, allowing him to eavesdrop into their conversations. Janoth’s wealth and power is signalled through the huge, ornate lobby of the Janoth Corporation building, which is overlooked by the enormous timepiece (the ‘big clock’ of the film’s title) in which, in the film’s opening sequence, Stroud is shown hiding – a snake in the proverbial grass (or in modern parlance, a corporate ‘whistleblower’). Interestingly, the novel features no such huge timepiece: in Fearing’s book, the notion of ‘the big clock’ is a more generalised reference to time and the pressures of working to a deadline. Several times in the film, characters – particularly Georgette – remind Stroud how unhappy he is working for Janoth, and Stroud promises his wife that he will quit his job as the editor of Crimeways, sacrificing the financial security it offers, in order to work once again as a lowly reporter on a small newspaper in West Virginia. Stroud’s employment with Janoth is represented as a Faustian pact: Stroud’s honeymoon with his wife was interrupted by the call from Janoth Corp which offered Stroud his current position as editor of Crimeways, and in the years since Stroud hasn’t had a single holiday – and has never managed to ‘complete’ his honeymoon with his wife. ‘Ever since, I’ve been working 26 hours a day’, Stroud notes, ‘What does Janoth think I am, a clock with springs and gears instead of flesh and blood?’ (‘Sometimes I think you married that magazine instead of me’, Georgette complains later in the picture.) The Big Clock offers a critical perspective on the corporatisation of life in the Twentieth Century, Janoth being depicted as an absurdly powerful man within an absurdly powerful company. (‘Isn’t it a pity that the wrong people always have money’, a character observes at one point.) As the film opens, the Janoth Corporation is facing the squeeze from new media outlets: in the boardroom, Janoth reminds his employees that the company is facing ‘dynamic competitors: radio, television, newsreels. And we must anticipate trends before they are trends. We are, in effect, clairvoyants’. Laughton’s obesity, used here as a signifier of self-indulgence, is accompanied by a sneering, haughty manner. He has installed covert surveillance equipment in the offices of his employees, allowing him to eavesdrop into their conversations. Janoth’s wealth and power is signalled through the huge, ornate lobby of the Janoth Corporation building, which is overlooked by the enormous timepiece (the ‘big clock’ of the film’s title) in which, in the film’s opening sequence, Stroud is shown hiding – a snake in the proverbial grass (or in modern parlance, a corporate ‘whistleblower’). Interestingly, the novel features no such huge timepiece: in Fearing’s book, the notion of ‘the big clock’ is a more generalised reference to time and the pressures of working to a deadline. Several times in the film, characters – particularly Georgette – remind Stroud how unhappy he is working for Janoth, and Stroud promises his wife that he will quit his job as the editor of Crimeways, sacrificing the financial security it offers, in order to work once again as a lowly reporter on a small newspaper in West Virginia. Stroud’s employment with Janoth is represented as a Faustian pact: Stroud’s honeymoon with his wife was interrupted by the call from Janoth Corp which offered Stroud his current position as editor of Crimeways, and in the years since Stroud hasn’t had a single holiday – and has never managed to ‘complete’ his honeymoon with his wife. ‘Ever since, I’ve been working 26 hours a day’, Stroud notes, ‘What does Janoth think I am, a clock with springs and gears instead of flesh and blood?’ (‘Sometimes I think you married that magazine instead of me’, Georgette complains later in the picture.)

The film hints at the homosexuality of Jonath, who surrounds himself with men – including Steve, who may or may not be Jonath’s lover – and is in one scene shown being given a massage by Jonath’s silent bodyguard Bill (Harry Morgan). In Fearing’s novel, the references to Jonath’s homosexuality are more overt, the murder taking place as an outcome of an argument between Pauline and Janoth during which the pair ‘trade accusations of what appear to be uncontrolled sexual activity coded as deviancy’ (Wald, op cit.: 39). Janoth accuses Pauline of having numerous male lovers and implies she has taken female lovers too; and Pauline retaliates by suggesting that he is a repressed homosexual and has been flaunting a covert sexual relationship with his subordinate Steve Hagen (‘Did I ever see you together when you weren’t camping?’; ‘camping’ in this instance refers to two men who are concealing a gay relationship), going so far as to describe Hagen as ‘that fairy gorilla’.  By contrast, in Farrow’s film adaptation Stroud is innocent throughout. Pauline helps Stroud to articulate his dissatisfaction with the Janoth Corporation and come to a decision to leave Janoth’s employ. Pauline and Stroud’s relationship is chaste: she gives him the ‘come on’ and he politely turns her down, reminding her that he is married and very much committed to his wife. Nevertheless, they find one another sympathetic: both of them have been exploited by the cruel Janoth and have a proverbial axe to grind. (‘You know the inside Janoth; I know the outside’, Pauline tells Stroud.) On the other hand, in Fearing’s novel it is made very clear that Stroud has a sexual relationship with Pauline Delos (her surname in the film is, of course, York): the guilt at his affair with Pauline is displaced onto his involvement in her murder (as a witness, and to others as a suspect). By contrast, in Farrow’s film adaptation Stroud is innocent throughout. Pauline helps Stroud to articulate his dissatisfaction with the Janoth Corporation and come to a decision to leave Janoth’s employ. Pauline and Stroud’s relationship is chaste: she gives him the ‘come on’ and he politely turns her down, reminding her that he is married and very much committed to his wife. Nevertheless, they find one another sympathetic: both of them have been exploited by the cruel Janoth and have a proverbial axe to grind. (‘You know the inside Janoth; I know the outside’, Pauline tells Stroud.) On the other hand, in Fearing’s novel it is made very clear that Stroud has a sexual relationship with Pauline Delos (her surname in the film is, of course, York): the guilt at his affair with Pauline is displaced onto his involvement in her murder (as a witness, and to others as a suspect).

The Big Clock is filled with a wonderful cast (Milland; Laughton; O’Sullivan; Macready; Harry Morgan). However, amongst some universally strong performances, the highlight is arguably Elsa Lanchester’s role as the artist Mrs Patterson. Patterson is introduced in the background, as Stroud purchases one of her paintings, unaware that the artist is standing next to him. She chastises him over the price he is willing to pay for her painting. She reappears later in the story, when Janoth catches wind of the fact that the witness in his murder of Pauline bought one of Patterson’s paintings and, on the back of this information, sends Klausmeyer (Harold Vermilyea) – the art critic of Artways magazine – to interview Mrs Patterson. Immediately, Patterson recognises Klausmeyer as the man who reviewed her exhibition in ’41. ‘I’ve been meaning to kill you for years’, she says dryly. Patterson has five children: three of these are the product of her marriage to her three previous husbands, ‘and the twins are Mike’s’. ‘Your present husband?’, Klausmeyer asks. ‘Would be if I could find him’, Patterson responds. Klausmeyer tells Patterson that he is trying to find a man who bought one of her paintings. ‘So have I, for 15 years’, she quips back. As Klausmeyer leaves, he stumbles and falls badly. ‘Oh, Penelope’, Patterson asserts insincerely, ‘You’ve forgotten to put away your roller skates’. It’s a dryly humorous role that plays with stereotypes of artists, and Lanchester plays it perfectly. Later, she is invited to Janoth Corporation by Janoth, who asks Patterson to sketch the likeness of the man who bought her painting. There, she meets Stroud and becomes sympathetic to him – so much so that when Janoth asks her to show him the sketch she has made, she reveals an abstract, symbolic image: ‘I think I’ve captured his mood rather successfully’, she says before laughing shrilly. Writing about Kenneth Fearing’s source novel, Alan M Wald has noted that The Big Clock hinges on the contrast between two unmarried women: Pauline Delos (or York, in the film adaptation), the blonde who is blackmailing Janoth (over what, we don’t know; she may also be involved in a sexual affair with him, or it may be over his relationship with Steve) and receiving payments through Hagen. In contrast with her is Louise Patterson, the eccentric brunette painter who has a stack of children and, having previously been married three times, is desperately attempting to find husband number four (Wald, 2012: 39). Both women function as an ally to Stroud, helping him to escape from the clutches of Janoth – both in terms of his contract of employment with Janoth Corporation and in terms of Janoth’s attempts to eliminate Stroud as a witness to the murder of Pauline.

Video

Taking up 26Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, The Big Clock is presented in Arrow’s Blu-ray in 1080p using the AVC codec. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1 and is sourced, according to Arrow’s promotional material, from unspecified ‘original film elements’. The film is uncut and runs for 95:24 mins. Taking up 26Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, The Big Clock is presented in Arrow’s Blu-ray in 1080p using the AVC codec. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1 and is sourced, according to Arrow’s promotional material, from unspecified ‘original film elements’. The film is uncut and runs for 95:24 mins.

Combined with some innovative production design, the film’s photography, by John F Seitz, masterfully emphasises the different spaces within the Janoth Corporation headquarters, which is the setting for most of the film: from the shadowy interior of the titular ‘big clock’ that overlooks the lobby to the bright elevators; from the large corporate boardroom to the contrasting interiors of Stroud’s and Janoth’s offices. The film’s opening sequence features some particularly expressive low-key lighting as Stroud skulks through the corridors of the Janoth Corporation at night and conceals himself within the mechanism of the big clock in the foyer of the building. This presentation is very pleasing. The film’s 35mm monochrome photography is communicated very well throughout. A substantial level of fine detail is present throughout the film and noticeable particularly in close-ups. Damage is limited to some minor density fluctuations in the emulsions and some very infrequent vertical scratches. Contrast levels are very good, with some well-defined midtones and a sharp drop-off into the toe. Finally, the encoded to disc is strong and ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film. Full-sized screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track. This is rich and deep, with good range and no distortion. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included, and these are easy to read and accurate in transcribing the film’s dialogue.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- Audio commentary with Adrian Martin. The Australian film critic talks about The Big Clock, reflecting on its relationship with its source novel and discussing how it ‘fits’ in terms of its relationship with the paradigms of late-1940s films noir. Martin suggests the film is the ‘combination’ of novelist Kenneth Fearing, screenwriter Jonathan Latimer and director John Farrow – all of whom were published writers. - ‘Turning Back the Clock’ (23:01). Critic Adrian Wootton talks about how unique The Big Clock is in terms of its position within American films noir of the late 1940s. He discusses Kenneth Fearing’s source novel and Jonathan Latimer’s approach to adapting it for the screen. Wootton also considers the parallels between The Big Clock and the Thin Man pictures, suggesting that the film’s moments of humour in its early sequences seem to align it more with the comedy genre than the thriller, but as the story progresses the thriller elements become more prevalent. - ‘A Difficult Actor’ (17:31). Simon Callow offers an excellent appraisal of Laughton’s career during the 1940s, considering how it had evolved to that point and the manner in which it would progress in subsequent years. Callow suggests that Laughton ‘lost his way’ somewhat after The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (William Dieterle, 1939), arguing that his performance as Quasimodo ‘burnt him out in some ways’. However, Callow suggests, Laughton is ‘on top form’ in The Big Clock. However, Callow offers that some of onscreen tension between Laughton and Milland benefitted from Milland’s dislike of the fact that Laughton was gay. - Lux Radio Theatre: The Big Clock (59:28). This 1948 radio dramatization of The Big Clock features Ray Milland and Maureen O’Sullivan reprising their roles from the feature film version of the story. - Trailer (2:21). - Gallery: Posters and Press (0:21); Promotional Stills (1:48).

Overall

Part of The Big Clock’s success is, at least, owing to screenwriter Jonathan Latimer’s recognition that some of the more abstract concepts in Fearing’s novel (for example, the notion of ‘the big clock’ as a metaphor for the pressures of time) could be, or needed to be, translated into physical objects for the film adaptation – in other words, practising the classic screenwriting dictum of ‘show, don’t tell’. Thus, Latimer’s script incorporates a huge clock which overshadows the lobby of Janoth Corporation’s headquarters, and in whose massive internal mechanism Stroud conceals himself. The clock becomes a symbol of Janoth’s ambition and ostentation. And, in Latimer’s screenplay, it’s a timepiece (a sundial) with which Janoth murders Pauline (in Fearing’s novel, Janoth kills her with a decanter), adding another layer of symbolism to the film’s references to clocks. The murder takes place as an outgrowth of the secrecy and desperation that the corporate environment engenders. There’s a great piece of sententia in Clifford Odets’ script for Alexander Mackendrick’s Sweet Smell of Success (1957), when the slimey Walter Winchell-esque columnist J J Hunsecker (Burt Lancaster) tells press agent Sidney Falco (Tony Curtis) that ‘My right hand hasn’t seen my left hand in 30 years’. Hunsecker is perverting the dictum expressed in Matthew 6:3 (‘When thou doest alms, let not thy left hand know what thy right hand doeth’) which suggests that acts of charity should be kept secret rather than performed for praise or approval; Hunsecker is of course suggesting that his more nefarious acts are kept secret. There’s a very similar moment in The Big Clock, made a decade prior to Sweet Smell of Success: discussing Janoth’s business dealings, Pauline tells George, ‘He [Janoth] doesn’t want to let his left hand know whose pocket the right one is picking’. As Janoth, Laughton’s presence overshadows the picture. However, in truth Elsa Lanchester’s performance as the scatty artist Mrs Patterson is so strong that it almost steals the film. Certainly, Lanchester’s scenes are the most memorable in the picture, and in the contextual material on this disc Adrian Wootton is on-point in his assertion that The Big Clock straddles the worlds of the comedy and the thriller picture. Part of The Big Clock’s success is, at least, owing to screenwriter Jonathan Latimer’s recognition that some of the more abstract concepts in Fearing’s novel (for example, the notion of ‘the big clock’ as a metaphor for the pressures of time) could be, or needed to be, translated into physical objects for the film adaptation – in other words, practising the classic screenwriting dictum of ‘show, don’t tell’. Thus, Latimer’s script incorporates a huge clock which overshadows the lobby of Janoth Corporation’s headquarters, and in whose massive internal mechanism Stroud conceals himself. The clock becomes a symbol of Janoth’s ambition and ostentation. And, in Latimer’s screenplay, it’s a timepiece (a sundial) with which Janoth murders Pauline (in Fearing’s novel, Janoth kills her with a decanter), adding another layer of symbolism to the film’s references to clocks. The murder takes place as an outgrowth of the secrecy and desperation that the corporate environment engenders. There’s a great piece of sententia in Clifford Odets’ script for Alexander Mackendrick’s Sweet Smell of Success (1957), when the slimey Walter Winchell-esque columnist J J Hunsecker (Burt Lancaster) tells press agent Sidney Falco (Tony Curtis) that ‘My right hand hasn’t seen my left hand in 30 years’. Hunsecker is perverting the dictum expressed in Matthew 6:3 (‘When thou doest alms, let not thy left hand know what thy right hand doeth’) which suggests that acts of charity should be kept secret rather than performed for praise or approval; Hunsecker is of course suggesting that his more nefarious acts are kept secret. There’s a very similar moment in The Big Clock, made a decade prior to Sweet Smell of Success: discussing Janoth’s business dealings, Pauline tells George, ‘He [Janoth] doesn’t want to let his left hand know whose pocket the right one is picking’. As Janoth, Laughton’s presence overshadows the picture. However, in truth Elsa Lanchester’s performance as the scatty artist Mrs Patterson is so strong that it almost steals the film. Certainly, Lanchester’s scenes are the most memorable in the picture, and in the contextual material on this disc Adrian Wootton is on-point in his assertion that The Big Clock straddles the worlds of the comedy and the thriller picture.

Arrow’s Blu-ray release of The Big Clock contains a very good presentation of the main feature. The source exhibits some minor wear and tear but nothing detrimental, and on the whole it’s a pleasingly film-like presentation of the picture. The film is accompanied on the disc by some superb contextual material: Callow, Wootton and Martin are always astute interviewees, and their comments here enrich one’s understanding of the film. References: Wald, Alan M, 2012: American Night: The Literary Left in the Era of the Cold War. The University of North Carolina Press Please click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|