|

|

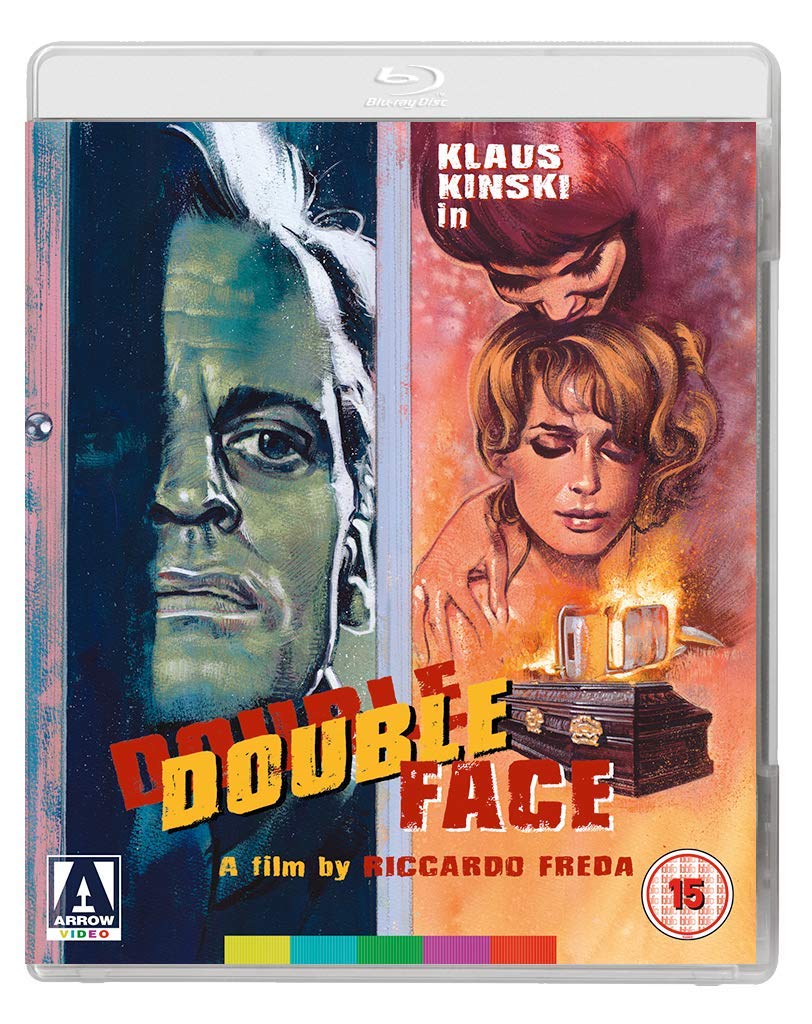

Double Face AKA A doppia faccia AKA Das Gesicht im Dunkeln AKA Liz et Helen (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (25th July 2019). |

|

The Film

A doppia faccia (Double Face, Riccardo Freda, 1969) A doppia faccia (Double Face, Riccardo Freda, 1969)

Synopsis: After a whirlwind romance on holiday in the Swiss Alps, John Alexander (Klaus Kinski) marries the beautiful Helen Brown (Margaret Lee). Helen is an heiress, her mother having bequeathed to Helen 90% of the company that is managed by Helen’s father (Sydney Chaplin). However, two years after their marriage John finds his dreams shattered: Helen is a cold and unaffectionate bride, preferring to spend time with her friend – and perhaps lover – Liz (Annabella Incontrera). When Helen is killed after someone plants a bomb in her car, the body destroyed beyond recognition and the murder made to look like an accident, John discovers he is named in his wife’s will as her sole heir. He inherits 90% of her father’s company. John retreats to Europe in order to grieve privately, but when he returns to England he discovers that the team of Inspector Gordon of Scotland Yard and Inspector Stevens of Liverpool consider Helen’s death to be murder, though there is little evidence to prove this, and suspect John of having caused it. John returns to his marital home, and there he discovers a squatter, a young woman named Christine. Christine propositions John, but he turns her down. John offers to drive Christine back to town; there, she steals his car keys and leads him into a nightclub where, in a back room, a makeshift cinema has been set up. On the screen plays a silent pornographic loop featuring Christine and another woman, who John identifies as Helen by her distinctive ring and scar on the back of her neck. John demands that Christine help him get in touch with the pornographer, Peter Nader, who made the loop. As John is drawn deeper into the sexual netherworld of pornographic loops and other seedy behaviours, his personality begins to unravel; Inspectors Gordon and Stevens are clearly convinced John had some involvement in Helen’s death too.  Critique: There was a time, during the 1980s, when for English-speaking fans of the thrilling all’italiana or giallo all’italiana (Italian-style thriller), the Italian thriller was defined by the unholy trinity of Mario Bava, Antonio Margheriti and Riccardo Freda, whose pictures were valourised in publications such as Alan Frank’s Horror Movies (1977) and The Aurum Film Encyclopedia: Horror (1988). However, in the early days of digital home video, whilst Mario Bava’s films found reasonable enough releases through the likes of Image Entertainment and Anchor Bay, owing to a variety of reasons Freda and Margheriti’s thrillers were for a number of years not served as well as those of other practitioners of the form (such as Sergio Martino, for example, whose work was previously dismissed as pedestrian-like). To some extent, this led to Freda and Margheriti’s work being sidelined in discussions of the Italian thriller amongst English-speaking fans of the thrilling, especially those for whom DVD releases of such films were their first exposure to the form. Critique: There was a time, during the 1980s, when for English-speaking fans of the thrilling all’italiana or giallo all’italiana (Italian-style thriller), the Italian thriller was defined by the unholy trinity of Mario Bava, Antonio Margheriti and Riccardo Freda, whose pictures were valourised in publications such as Alan Frank’s Horror Movies (1977) and The Aurum Film Encyclopedia: Horror (1988). However, in the early days of digital home video, whilst Mario Bava’s films found reasonable enough releases through the likes of Image Entertainment and Anchor Bay, owing to a variety of reasons Freda and Margheriti’s thrillers were for a number of years not served as well as those of other practitioners of the form (such as Sergio Martino, for example, whose work was previously dismissed as pedestrian-like). To some extent, this led to Freda and Margheriti’s work being sidelined in discussions of the Italian thriller amongst English-speaking fans of the thrilling, especially those for whom DVD releases of such films were their first exposure to the form.

Fundamentally, the giallo all’italiana is a difficult beast to capture; though amongst English-speaking fans the Italian thriller has, at least superficially, come to be associated with a remarkably narrow group of films that feature a similar set of paradigms (including, but not limited to, black-gloved killers, psychosexual terror and voyeurism), the Italian thrillers of the 1960s and 1970s were in actuality remarkably diverse. Strong parallels may be drawn between the Italian thriller and the American film noir – in the sense that both groups of films have come to be defined, somewhat reductively, by a cherry-picked selection of films, and that both may be considered a ‘style’ rather than a ‘genre’ in the true sense. Where for Italian audiences, a giallo was (and remains) simply a thriller of any country of origin (for example, in terms of 1960s cinema, from Hitchcock’s Psycho to Karel Reisz’s remake of Night Must Fall), in the fan discourse of English-speaking cinephiles during the 1980s and 1990s the label giallo came to be associated with a narrower group of Italian productions (and coproductions) made predominantly between the 1960s and, broadly speaking, the late 1980s. For Italian audiences, these films were defined by the addition of a further descriptor: the giallo all’italiana (or the thrilling all’italiana) – the ‘Italian style’ within this group of films being as important as the Italian style of the western all’italiana (or ‘Spaghetti Western’), inasmuch as it speaks of a unique flavour within a genre that knows no boundaries: in other words, a localised variant of an international form. As if to reinforce this, Double Face was based on a book, The Face in the Night (1926), by English novelist Edgar Wallace, whose novels are arguably most closely associated with the German krimi pictures – though Wallace’s work did form the core of several examples of the Italian-style thriller (often coproduced by West German production companies with an eye on their domestic market) including, most notably, Massimo Dallamano’s Cosa avete fatto a Solange? (What Have You Done to Solange, 1972, the Arrow Video release of which has been reviewed by us here) and Duccio Tessari’s Una farfalla con le ali insanguinate (The Bloodstained Butterfly, 1971, also released by Arrow Video on Blu-ray and reviewed by us here). Fundamentally, the giallo all’italiana is a difficult beast to capture; though amongst English-speaking fans the Italian thriller has, at least superficially, come to be associated with a remarkably narrow group of films that feature a similar set of paradigms (including, but not limited to, black-gloved killers, psychosexual terror and voyeurism), the Italian thrillers of the 1960s and 1970s were in actuality remarkably diverse. Strong parallels may be drawn between the Italian thriller and the American film noir – in the sense that both groups of films have come to be defined, somewhat reductively, by a cherry-picked selection of films, and that both may be considered a ‘style’ rather than a ‘genre’ in the true sense. Where for Italian audiences, a giallo was (and remains) simply a thriller of any country of origin (for example, in terms of 1960s cinema, from Hitchcock’s Psycho to Karel Reisz’s remake of Night Must Fall), in the fan discourse of English-speaking cinephiles during the 1980s and 1990s the label giallo came to be associated with a narrower group of Italian productions (and coproductions) made predominantly between the 1960s and, broadly speaking, the late 1980s. For Italian audiences, these films were defined by the addition of a further descriptor: the giallo all’italiana (or the thrilling all’italiana) – the ‘Italian style’ within this group of films being as important as the Italian style of the western all’italiana (or ‘Spaghetti Western’), inasmuch as it speaks of a unique flavour within a genre that knows no boundaries: in other words, a localised variant of an international form. As if to reinforce this, Double Face was based on a book, The Face in the Night (1926), by English novelist Edgar Wallace, whose novels are arguably most closely associated with the German krimi pictures – though Wallace’s work did form the core of several examples of the Italian-style thriller (often coproduced by West German production companies with an eye on their domestic market) including, most notably, Massimo Dallamano’s Cosa avete fatto a Solange? (What Have You Done to Solange, 1972, the Arrow Video release of which has been reviewed by us here) and Duccio Tessari’s Una farfalla con le ali insanguinate (The Bloodstained Butterfly, 1971, also released by Arrow Video on Blu-ray and reviewed by us here).

As Danny Shipka has noted, in an age in which international travel was becoming increasingly normalised, globalisation was an issue that was foregrounded in the gialli all’italiana of the late 1960s and 1970s, with ‘[i]ssues such as tourism, exoticism, hybridity and foreignness […] all incorporated into the giallo’ during this period (Danny Shipka, 2011: 80). A significant number of Italian-style thrillers ‘point up the problems that Italians had with their national identities’, featuring protagonists (often amateur sleuths) who were either foreigners in Italy (such as Sam Dalmas in Dario Argento’s L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo/The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, 1970), or Italians in foreign countries (ibid). Distinctive amongst this group were a series of Italian thrillers set in the UK, often London. These films offered an outsider’s view of some of the quirks of British life – from the impact of the counterculture during Sixties Britain to the class system – that is comparable to the manner in which Spanish filmmakers Jorge Grau and Jose Ramon Larraz took an askance view of British society in their 1970s horror pictures (including Grau’s 1974 zombie film No profaner el sueno de los muertos/The Living Dead at the Manchester Morgue and Larraz’s pictures Symptoms and Vampyres, both also released in 1974). Double Face is joined in its English setting by the likes of Lucio Fulci’s Una lucertola con la pelle di donna (A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin, 1971) and Il gatto nero (The Black Cat, 1981) – perhaps unsurprising, given that Fulci contributed to the writing of Double Face. Like Fulci’s A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin, Double Face juxtaposes straight bourgeois, patriarchal society with an anarchic, youth-oriented counterculture that is dominated by women (and also characterised by female homosexuality). As Danny Shipka has noted, in an age in which international travel was becoming increasingly normalised, globalisation was an issue that was foregrounded in the gialli all’italiana of the late 1960s and 1970s, with ‘[i]ssues such as tourism, exoticism, hybridity and foreignness […] all incorporated into the giallo’ during this period (Danny Shipka, 2011: 80). A significant number of Italian-style thrillers ‘point up the problems that Italians had with their national identities’, featuring protagonists (often amateur sleuths) who were either foreigners in Italy (such as Sam Dalmas in Dario Argento’s L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo/The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, 1970), or Italians in foreign countries (ibid). Distinctive amongst this group were a series of Italian thrillers set in the UK, often London. These films offered an outsider’s view of some of the quirks of British life – from the impact of the counterculture during Sixties Britain to the class system – that is comparable to the manner in which Spanish filmmakers Jorge Grau and Jose Ramon Larraz took an askance view of British society in their 1970s horror pictures (including Grau’s 1974 zombie film No profaner el sueno de los muertos/The Living Dead at the Manchester Morgue and Larraz’s pictures Symptoms and Vampyres, both also released in 1974). Double Face is joined in its English setting by the likes of Lucio Fulci’s Una lucertola con la pelle di donna (A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin, 1971) and Il gatto nero (The Black Cat, 1981) – perhaps unsurprising, given that Fulci contributed to the writing of Double Face. Like Fulci’s A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin, Double Face juxtaposes straight bourgeois, patriarchal society with an anarchic, youth-oriented counterculture that is dominated by women (and also characterised by female homosexuality).

Double Face offers a near-perfect role for Kinski, who – here, as in his role in Jess Franco’s Jack the Ripper (1976), for example – finds his habitat when skulking about in shadows, buttoned-up but exploding into sexual violence and madness. Any authority John might be presumed to have is swiftly undermined by the games-playing Christine, a childish young woman whose subversion of patriarchal authority might be taken as a metaphor for the era of Women’s Lib. Double Face is essentially a sexual nightmare. John marries Helen after a whirlwind romance but soon discovers she is unwilling to have sex with him, presumably owing to the fact that she is homosexual – something which is suggested in the plotting and dialogue but not addressed directly. When they return to England, John becomes frustrated at his sexless marriage, whilst Helen becomes involved with Liz and sidelines her husband. ‘She’s just like her mother’, Helen’s father warns John, ‘Rich, moody, wicked [….] You just have to get used to it, like I did with her mother’. The distance between John and Helen is signified in a scene in which they visit the races and sit apart, at opposite edges of the frame, facing away from one another and conversing whilst watching the offscreen action through their field glasses. Helen is planning to leave him when the ‘accident’ which apparently claims her life takes place. John retreats to Europe, presumably to grieve privately, and when he returns to England he encounters Christine. Christine is a young, promiscuous woman who propositions John sexually. John turns her down coldly, Kinski’s prissy body language and his coarse manner with this young woman suggesting more than simply aloofness: John is a tightly-wound spring who, in a later sequence, explodes in sexual fury, beating Christine sadistically. After their first encounter in John’s empty marital home, Christine leads John into the underbelly of the city, where in the back room of a nightclub he encounters the stag film in which Christine is shown being seduced by an older women who John identifies as Helen via her ring and the distinctive scar on her neck. Helen, meanwhile, is depicted as a sexual monster: scarred from her car accident, Christine claims Helen is referred to on-set as ‘The Countess’ and would perform ‘with such wanton pleasure’ that in one scene, Helen bit Christine on the neck, vampire-like, and demanded, ‘Always call me Helen’. Double Face offers a near-perfect role for Kinski, who – here, as in his role in Jess Franco’s Jack the Ripper (1976), for example – finds his habitat when skulking about in shadows, buttoned-up but exploding into sexual violence and madness. Any authority John might be presumed to have is swiftly undermined by the games-playing Christine, a childish young woman whose subversion of patriarchal authority might be taken as a metaphor for the era of Women’s Lib. Double Face is essentially a sexual nightmare. John marries Helen after a whirlwind romance but soon discovers she is unwilling to have sex with him, presumably owing to the fact that she is homosexual – something which is suggested in the plotting and dialogue but not addressed directly. When they return to England, John becomes frustrated at his sexless marriage, whilst Helen becomes involved with Liz and sidelines her husband. ‘She’s just like her mother’, Helen’s father warns John, ‘Rich, moody, wicked [….] You just have to get used to it, like I did with her mother’. The distance between John and Helen is signified in a scene in which they visit the races and sit apart, at opposite edges of the frame, facing away from one another and conversing whilst watching the offscreen action through their field glasses. Helen is planning to leave him when the ‘accident’ which apparently claims her life takes place. John retreats to Europe, presumably to grieve privately, and when he returns to England he encounters Christine. Christine is a young, promiscuous woman who propositions John sexually. John turns her down coldly, Kinski’s prissy body language and his coarse manner with this young woman suggesting more than simply aloofness: John is a tightly-wound spring who, in a later sequence, explodes in sexual fury, beating Christine sadistically. After their first encounter in John’s empty marital home, Christine leads John into the underbelly of the city, where in the back room of a nightclub he encounters the stag film in which Christine is shown being seduced by an older women who John identifies as Helen via her ring and the distinctive scar on her neck. Helen, meanwhile, is depicted as a sexual monster: scarred from her car accident, Christine claims Helen is referred to on-set as ‘The Countess’ and would perform ‘with such wanton pleasure’ that in one scene, Helen bit Christine on the neck, vampire-like, and demanded, ‘Always call me Helen’.

From this point, John draws himself deeper into the seedy world of John Lindsay-esque porno loop producer Peter, in an attempt to find Helen and prove she is still alive; it’s not a stretch to say that John is like Orpheus descending into the underworld to rescue Eurydice, and there are strong parallels between John’s journey and the similar plotting of later films such as Paul Schrader’s Hardcore (1979) and David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1982). In Hardcore, of course, George C Scott’s conservative businessman Jake VanDorn ventures into the underbelly of California porno producers in an effort to find his runaway daughter (Season Hubley); in Videodrome, television executive Max Renn (James Woods) is pulled into the world of ‘snuff’ television when his masochistic lover, Nicki Brand (Deborah Harry), leaves him to audition for a role in Videodrome, a plotless Pittsburgh-based show in which the ‘contestants’ are tortured sexually and murdered onscreen. In Double Face, the stag film John witnesses is like the Zapruder footage: apparent evidence of a conspiracy that nevertheless is open to interpretation. Towards the end of the film, John acquires a copy of the porno loop and, at home, plays it obsessively. Seeing the evidence he needs (Helen’s ring and scar), he shows the loop to Helen’s father; but this time, the ring and scar are missing. ‘You’ve talked yourself into something that doesn’t exist’, Helen’s father asserts. From this point, John draws himself deeper into the seedy world of John Lindsay-esque porno loop producer Peter, in an attempt to find Helen and prove she is still alive; it’s not a stretch to say that John is like Orpheus descending into the underworld to rescue Eurydice, and there are strong parallels between John’s journey and the similar plotting of later films such as Paul Schrader’s Hardcore (1979) and David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1982). In Hardcore, of course, George C Scott’s conservative businessman Jake VanDorn ventures into the underbelly of California porno producers in an effort to find his runaway daughter (Season Hubley); in Videodrome, television executive Max Renn (James Woods) is pulled into the world of ‘snuff’ television when his masochistic lover, Nicki Brand (Deborah Harry), leaves him to audition for a role in Videodrome, a plotless Pittsburgh-based show in which the ‘contestants’ are tortured sexually and murdered onscreen. In Double Face, the stag film John witnesses is like the Zapruder footage: apparent evidence of a conspiracy that nevertheless is open to interpretation. Towards the end of the film, John acquires a copy of the porno loop and, at home, plays it obsessively. Seeing the evidence he needs (Helen’s ring and scar), he shows the loop to Helen’s father; but this time, the ring and scar are missing. ‘You’ve talked yourself into something that doesn’t exist’, Helen’s father asserts.

Double Face also bears comparison with Boileau and Narcejac’s Les diaboliques (1951), memorably filmed by Henri-Georges Clouzot in 1955; as in Les diaboliques, the mystery in Double Face revolves around a character (Helen) who is absent, presumed dead, but whose presence is felt through the discovery of various artefacts which suggest she may still be alive. When John returns to the marital home following his time in Europe, he discovers the house filled with the sound of Nora Orlandi’s main theme. Is the marital home haunted by the ghost of Helen? Upon investigation, John finds this song to be playing on a reel-to-reel tape deck in one of the upstairs bedrooms, which squatter Christine has made her home. Double Face also bears comparison with Boileau and Narcejac’s Les diaboliques (1951), memorably filmed by Henri-Georges Clouzot in 1955; as in Les diaboliques, the mystery in Double Face revolves around a character (Helen) who is absent, presumed dead, but whose presence is felt through the discovery of various artefacts which suggest she may still be alive. When John returns to the marital home following his time in Europe, he discovers the house filled with the sound of Nora Orlandi’s main theme. Is the marital home haunted by the ghost of Helen? Upon investigation, John finds this song to be playing on a reel-to-reel tape deck in one of the upstairs bedrooms, which squatter Christine has made her home.

Like a significant number of Freda’s other films (including his slightly later thrilling, 1971’s L’iguana dalla lingua di fuoco/Iguana with the Tongue of Fire, recently released on Blu-ray by Arrow Video and reviewed by us here), Double Face explores a theme that Freda inherited from the paradigms of Gothic fiction – of the emptiness, ennui and anomie that characterise the lives of the wealthy. The film juxtaposes the privileged (John and his social class) with the riff-raff (the young people with whom Christine is associated), age with youth, ‘straight’ society and the counterculture. This is reflected in the story-spaces used in the film: the luxurious interior of John’s country home, with its lavish and excessive furnishings (eg, a book kept on a nightstand which opens to reveal a bottle of hard liquor within it), with the dingy spaces associated with Christine and the other youths: the dark nightclub, lit by primary-coloured gels which spin about vertiginously, in which young men riding motorcycles circle a crowd, tearing the clothes off young women as they pass them. This warehouse-like space, in which beatniks and bikers coalesce alongside young women dressed in tie-dyed shirts and dresses, is comparable to the ‘straight’ view of countercultural nightclubs in John Boorman’s Point Blank (1967) and the Pigeon-Toed Orange Peel in Don Siegel’s Coogan’s Bluff (1968). In Double Face, the strait-laced Kinski is as much at odds with the young people in the nightclub as Lee Marvin or Clint Eastwood in their respective films. Repression is contrasted with licentiousness, day is set against night, and the patriarch (John, again) is juxtaposed with the nymph (Christine), the latter leading the former into a world in which order has been subverted. There are similarities here, if one looks for them, with some of the much later American yuppie-in-peril movies, in which young women lure men into dangerous urban spaces – such as John Landis’ Into the Night (1985), Martin Scorsese’s After Hours (also 1985) and Jonathan Demme’s Something Wild (1986). Like a significant number of Freda’s other films (including his slightly later thrilling, 1971’s L’iguana dalla lingua di fuoco/Iguana with the Tongue of Fire, recently released on Blu-ray by Arrow Video and reviewed by us here), Double Face explores a theme that Freda inherited from the paradigms of Gothic fiction – of the emptiness, ennui and anomie that characterise the lives of the wealthy. The film juxtaposes the privileged (John and his social class) with the riff-raff (the young people with whom Christine is associated), age with youth, ‘straight’ society and the counterculture. This is reflected in the story-spaces used in the film: the luxurious interior of John’s country home, with its lavish and excessive furnishings (eg, a book kept on a nightstand which opens to reveal a bottle of hard liquor within it), with the dingy spaces associated with Christine and the other youths: the dark nightclub, lit by primary-coloured gels which spin about vertiginously, in which young men riding motorcycles circle a crowd, tearing the clothes off young women as they pass them. This warehouse-like space, in which beatniks and bikers coalesce alongside young women dressed in tie-dyed shirts and dresses, is comparable to the ‘straight’ view of countercultural nightclubs in John Boorman’s Point Blank (1967) and the Pigeon-Toed Orange Peel in Don Siegel’s Coogan’s Bluff (1968). In Double Face, the strait-laced Kinski is as much at odds with the young people in the nightclub as Lee Marvin or Clint Eastwood in their respective films. Repression is contrasted with licentiousness, day is set against night, and the patriarch (John, again) is juxtaposed with the nymph (Christine), the latter leading the former into a world in which order has been subverted. There are similarities here, if one looks for them, with some of the much later American yuppie-in-peril movies, in which young women lure men into dangerous urban spaces – such as John Landis’ Into the Night (1985), Martin Scorsese’s After Hours (also 1985) and Jonathan Demme’s Something Wild (1986).

Video

Presented in 1080p using the AVC codec, Double Face was shot on 35mm colour stock and is presented here in its intended aspect ratio 1.85:1. Presented in 1080p using the AVC codec, Double Face was shot on 35mm colour stock and is presented here in its intended aspect ratio 1.85:1.

Double Face has been released in a variety of edits, including an abbreviated cut prepared for the German market and an alternate cut, released in France as Liz et Helen, which features added erotic footage. In the 1970s, Robert de Nesle added hardcore inserts featuring Alice Arno to the film and released it under the title Chaleur et jouissance. Arrow’s presentation of Double Face is uncut and runs for 91:26 mins, reflecting the original Italian edit of the picture. From the main menu, if the viewer selects to play the main feature, s/he will be asked to choose between the ‘Italian version’ and the ‘English version’; this choice determines both the spoken language and the language of the onscreen text. The film opens with some terribly funky-looking stock footage of the Swiss Alps, which quickly segues into some equally funky rear projection footage (of Kinski and Margaret Lee on a sledge, snow-capped mountains whizzing by behind them). When the film ‘proper’ begins, however, the photography is – aside from some model effects shots comparable in quality to the infamous model shots in Jean-Pierre Melville’s slightly later Un flic (1972) – very handsome. These sloppy effects shots are balanced by some clever editing, however: in for example, in the scene in which John infiltrates Peter Nader’s deserted studio, John is attacked whilst blinded by the studio lights; clever cuts in this scene convey the sense that the disoriented John does not know where the blows are coming from and who is delivering them. Based on a new 2k restoration of the film from the original negative, this presentation contains a very pleasing level of detail, fine detail being articulated richly in close-ups. Contrast levels are excellent. Low-light scenes feature depth and detail in the shadows, whilst the ascent into the shoulder is balanced and even. Midtones have strong definition. Damage is negligible, and colours are rich and naturalistic. The encode to disc presents no problems and ensures the presentation retains its film-like look, with the structure of 35mm film apparent throughout.

Some full-sized screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

The film can be played with either an Italian LPCM 1.0 track, with optional English subtitles translating the Italian dialogue, or an English LPCM 1.0 track, with optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. Language and subtitle options can be changed ‘on the fly’, whilst the film is playing. Both tracks are rich and deep, displaying strong range. The Italian and English mixes contain some interesting differences. In the Italian mix, the scene in which John returns to his marital home after spending time in Europe features a much louder version of the ‘phantom’ music John hears from upstairs, in comparison with the English track. Dialogue sometimes kicks in at a slightly different pace in both versions, and the Italian mix features a slightly different approach to sound design. For example, when John is led by Christine into the makeshift cinema where the porno loop is playing, in the English version that audience are mostly silent; but in the Italian version, reflecting the animism of audiences in more parochial areas of Italy generally, the audience catcalls throughout the screening. ‘They’re sadomasochists too!’, one of the youths in the audience asserts loudly. ‘Look, she’s going to ruin her necklace’, another says.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with Tim Lucas. Lucas provides a detailed and carefully-research commentary examining Double Face. Lucas begins by talking about the ‘problem’ of Double Face existing in a variety of different edits, which means that his commentary track, recorded without an awareness of which edit of the film it was to accompany, does not have a direct visual relationship with the onscreen action. Lucas talks about Freda’s career as a director, discussing how it evolved during the 1960s; Freda’s later films, Lucas argues, were hampered by the fact that production circumstances required Freda to work faster and cheaper. Lucas also talks at length about the film’s cast, reflecting in some detail on Kinski’s role in the picture and the position of Double Face within Kinski’s body of work. Lucas reflects on the origins of Double Face in Edgar Wallace’s novel, and considers the differences and areas of overlap between the giallo and the krimi. - ‘The Many Faces of Nora Orlandi’ (43:28). DJ and soundtrack enthusiast Lovely Jon discusses the work of composer Nora Orlandi, exploring Orlandi’s career and discussing her various collaborations with the likes of Alessandro Alessandroni – whose influence, Jon suggests, can be heard in Orlandi’s film scores. Jon talks about the diversity of Orlandi’s scores, reflecting on some specific examples such as Orlandi’s score for Romolo Girolami’s Il dolce corpo di Deborah (The Sweet Body of Deborah, 1968) and Riccardo Freda’s La morte non conta i dollari (Death at Owell Rock, 1967). Jon reflects on some detail on Orlandi’s score for Double Face.

- ‘7 Notes for a Murderer’ (32:18). Composer Nora Orlandi is interviewed about her work on film scores. She discusses the beginnings of her career. She reflects on her approach to scoring Spaghetti Westerns, offering an anecdote in which a nameless person working in the film industry (whom Orlandi later identifies in a roundabout way as Riccardo Freda) criticised her Western scores for all ‘sounding the same’, Orlandi arguing in response that there are only a limited set of paradigms within the Western – both in terms of its outer form (ie, its visual iconography) and the types of music associated with it. Orlandi says that Freda was ‘a provocateur’ who strove to be ‘both funny and mean at the same time’. Orlandi suggests this was ‘a silly cocktail’. She talks about the difficulties she had in working with Freda, who was critical of her scores initially but was soon put in his place by Orlandi. She says the tensions she experienced with Freda led to them ending their working relationship with Double Face. On the other hand, she discusses working with Romolo Girolami, which seems to have been a much more positive experience. Orlandi speaks in Italian; optional English subtitles are provided. - ‘The Terrifying Dr Freda’ (19:53). Critic Amy Simmons narrates a video essay looking at Freda’s career as a director. Simmons discusses the collaboration between Freda and Bava on I vampiri (1957), the forerunner of the Italian Gothic films of the 1960s – including Bava’s own La maschera del demonio (Mask of Satan/Black Sunday, 1960). From here, Simmons offers a brief appraisal of Freda’s films, in chronological order, offering particular consideration of L’orrible segreto del Dr Hichcock (The Horrible Dr Hichcock/The Terror of Dr Hichcock, 1963). - Image Galleries: German Pressbook (7 pages); German Promotional Materials (28 images); Italian Cineromanzo (63 images). The latter is particularly interesting: digesting the film’s narrative into comic book form, it incorporates some interesting imagery not seen in the finished film – including some much more copious nudity. - English Theatrical Trailer (3:32). - Italian Theatrical Trailer (3:32).

Overall

For a number of years, Riccardo Freda’s work was underrepresented on digital home video; and perhaps as a consequence of this, in critical discourse during the 2000s the director was sidelined somewhat in favour of directors whose work had previously been dismissed as workmanlike but which conversely became more accessible on the DVD format. However, previously Freda’s work had been spoken of in revered tones, in the pages of the likes of Alan Frank’s Horror Films and the Phil Hardy’s Aurum Film Encyclopedia: Horror. Certainly, there’s an unevenness in Freda’s body of work, with his later films feeling much more rushed and featuring corners which seem noticeably to have been cut. Perhaps ironically, it’s Freda’s later pictures which have, in the past few years, become available in pristine home video releases (such as Arrow’s recent Blu-ray release of L’iguana dalla lingua di fuoco/The Iguana with the Tongue of Fire, 1971, reviewed by us here). Sadly, Freda’s more outstanding Gothics, including The Horrible Dr Hichcock and Lo spettro (The Ghost, 1963), remain for various reasons frustratingly out of reach in terms of hi-def presentations (though Dr Hichcock has had a Blu-ray release in the States – but only of the cut English-dubbed variant of the picture). For a number of years, Riccardo Freda’s work was underrepresented on digital home video; and perhaps as a consequence of this, in critical discourse during the 2000s the director was sidelined somewhat in favour of directors whose work had previously been dismissed as workmanlike but which conversely became more accessible on the DVD format. However, previously Freda’s work had been spoken of in revered tones, in the pages of the likes of Alan Frank’s Horror Films and the Phil Hardy’s Aurum Film Encyclopedia: Horror. Certainly, there’s an unevenness in Freda’s body of work, with his later films feeling much more rushed and featuring corners which seem noticeably to have been cut. Perhaps ironically, it’s Freda’s later pictures which have, in the past few years, become available in pristine home video releases (such as Arrow’s recent Blu-ray release of L’iguana dalla lingua di fuoco/The Iguana with the Tongue of Fire, 1971, reviewed by us here). Sadly, Freda’s more outstanding Gothics, including The Horrible Dr Hichcock and Lo spettro (The Ghost, 1963), remain for various reasons frustratingly out of reach in terms of hi-def presentations (though Dr Hichcock has had a Blu-ray release in the States – but only of the cut English-dubbed variant of the picture).

Whilst not one of Freda’s best pictures, Double Face is an interesting picture; a sexual nightmare, there are some strong similarities between this picture and writer Lucio Fulci’s own films (as director) Una sull’altra (One on Top of the Other, 1968) and A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin. Kinski, in one of his first major roles, essays a type of character that he would return to throughout his career – somewhat passive, given to slinking about in the background, but exploding in moments of outrageousness. Like many of Freda’s pictures, Double Face explores the ennui of the privileged classes, connecting this to sexual perversion. Some of the effects work is noticeably shonky, suggesting the production was somewhat rushed, but on the other hand there is some superb photography (and, in particular, lighting) in many other sequences of the picture. Certainly, this release of Double Face is an important one, and is worth adding to the collection of any fan of the Italian thrilling/giallo all’italiana. The presentation of the main feature is superb and satisfyingly filmlike, and it is supported by some excellent contextual material – in particular, the superb interview with Nora Orlandi. References: Shipka, Danny, 2011: Perverse Titillation: The Exploitation Cinema of Italy, Spain and France, 1960-1980. London: McFarland Please click to enlarge.

|

|||||

|