|

|

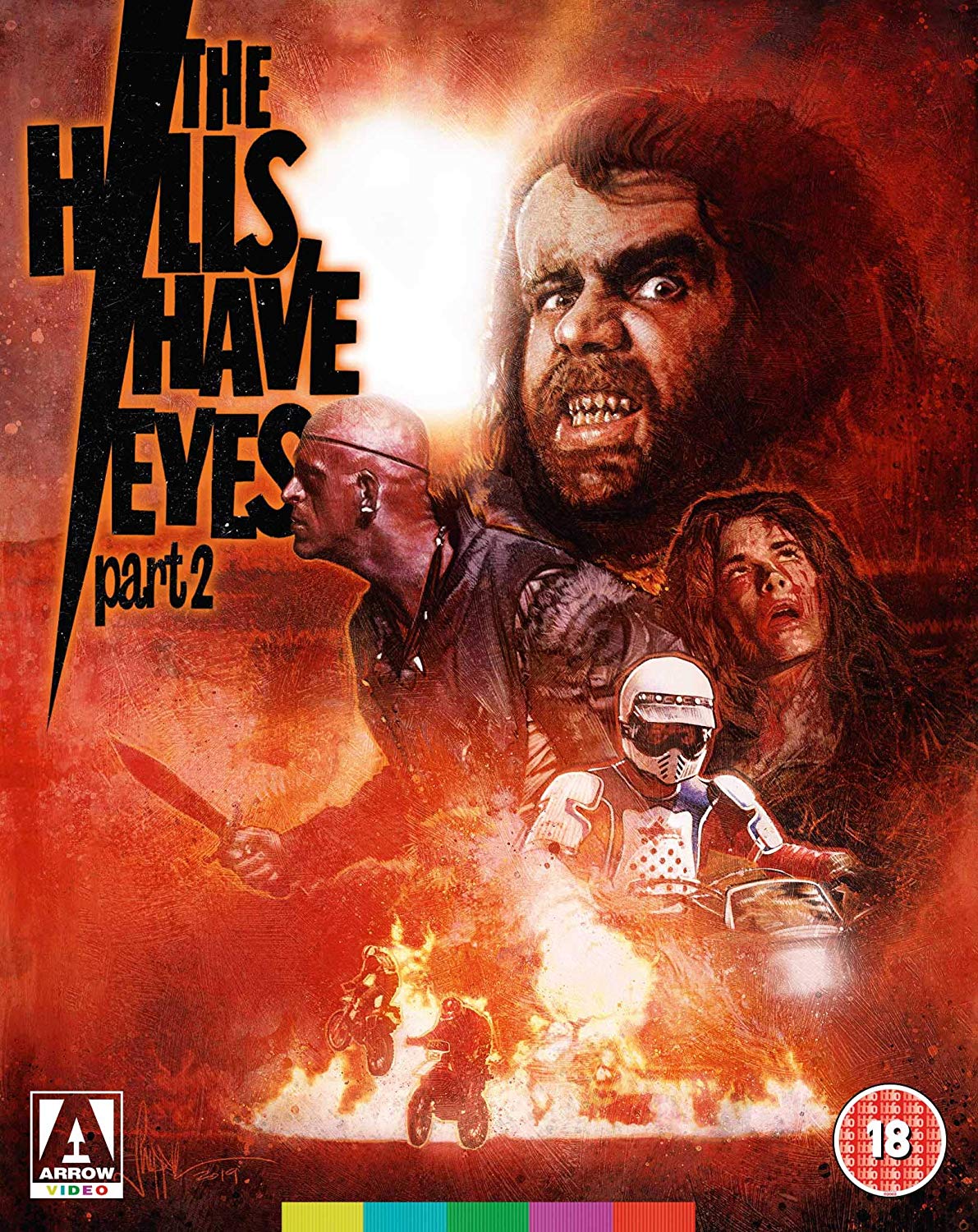

Hills Have Eyes Part II (The) AKA The Hills Have Eyes Part 2 (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (3rd October 2019). |

|

The Film

The Hills Have Eyes, Part II (Wes Craven, 1984) The Hills Have Eyes, Part II (Wes Craven, 1984)

Synopsis: Having survived the events of The Hills Have Eyes (Craven, 1977), Bobby (Robert Houston) is crippled with nightmares involving his family’s encounter in the desert with the cannibalistic clan headed by Jupiter (James Whitworth). In the years since, Bobby has developed a super-fuel with the intention that it will be used by a team of motocross riders in a race, hopefully leading to a corporate buyer for Bobby’s formula; however, to get to the site of the race, Bobby and the motocross riders must travel close to the area of the Nevada desert in which the events of the first film took place. As the crew prepare to depart in the red bus that will carry both the bikes and their riders, Bobby suffers a crippling panic attack and is supported by ‘Rachel’ (Janus Blythe) – who is actually Ruby, the daughter of Jupiter, who Bobby and the others rescued from her family at the climax of the first film. Bobby decides to stay behind, with Ruby orchestrating the group on the bus – consisting of mechanic Hulk (John Laughlin), Roy (Kevin Blair) and his blind girlfriend Cass (Tamara Stafford), Harry (Peter Frechette) and Jane (Colleen Riley), and Foster (Willard Pugh) and his lover Sue (Penny Johnson). Also on the bus is Beast, Bobby’s dog, who played a pivotal role in fending off Jupiter’s cruel son Pluto (Michael Berryman) during the events of the first film.  Realising that they have forgotten to account for the end of Daylight Savings Time and must therefore reach their destination an hour sooner than they planned, the group decide to take a short-cut across the desert. However, the fuel tank on the bus is ruptured and the bus breaks down near the head of an abandoned mine. There, they are watched from a distance by Pluto, who since the death of Jupiter has teamed up with his uncle, known only as The Reaper (John Bloom). Together, Pluto and The Reaper have been killing and eating unwary visitors to the area, dumping their mutilated corpses down one of the mine shafts. Realising that they have forgotten to account for the end of Daylight Savings Time and must therefore reach their destination an hour sooner than they planned, the group decide to take a short-cut across the desert. However, the fuel tank on the bus is ruptured and the bus breaks down near the head of an abandoned mine. There, they are watched from a distance by Pluto, who since the death of Jupiter has teamed up with his uncle, known only as The Reaper (John Bloom). Together, Pluto and The Reaper have been killing and eating unwary visitors to the area, dumping their mutilated corpses down one of the mine shafts.

By stealing one of the group’s motorbikes, Pluto lures Roy and Harry away from the others. Harry is killed whilst Roy is left for dead. When the pair don’t return, the other members of the group wonder if Harry and Roy are pulling a practical joke. As night descends, they set up camp in one of the mine buildings, whilst Ruby and Hulk search outside for Roy and Harry. However, soon members of the group are separated from the others, falling prey to Pluto and The Reaper.  Critique: The Hills Have Eyes, Part II (Wes Craven, 1984) conforms to the paradigms of the slasher subgenre, including featuring during its climax a conflict between the antagonist and the ‘Final Girl’ – in this case, the blind Cass. (Cass’ visual impairment can’t help but bring to mind Audrey Hepburn’s stand-off against Alan Arkin’s antagonist in Terence Young’s 1967 film Wait Until Dark.) Craven shot most of The Hills Have Eyes, Part II prior to making the iconic A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), though the latter film was of course released slightly before The Hills Have Eyes, Part II. A film burdened by its reputation for bulking out its running time with lengthy and innumerable flashbacks to the first The Hills Have Eyes (Craven, 1977), The Hills Have Eyes, Part II was famously only about two thirds through its production phase when the producers pulled the plug; it was only after the phenomenal success of A Nightmare on Elm Street that they asked Craven to complete The Hills Have Eyes, Part II, assembling a complete edit of the picture from what had already been photographed and padding the film out with footage from the original The Hills Have Eyes. Critique: The Hills Have Eyes, Part II (Wes Craven, 1984) conforms to the paradigms of the slasher subgenre, including featuring during its climax a conflict between the antagonist and the ‘Final Girl’ – in this case, the blind Cass. (Cass’ visual impairment can’t help but bring to mind Audrey Hepburn’s stand-off against Alan Arkin’s antagonist in Terence Young’s 1967 film Wait Until Dark.) Craven shot most of The Hills Have Eyes, Part II prior to making the iconic A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), though the latter film was of course released slightly before The Hills Have Eyes, Part II. A film burdened by its reputation for bulking out its running time with lengthy and innumerable flashbacks to the first The Hills Have Eyes (Craven, 1977), The Hills Have Eyes, Part II was famously only about two thirds through its production phase when the producers pulled the plug; it was only after the phenomenal success of A Nightmare on Elm Street that they asked Craven to complete The Hills Have Eyes, Part II, assembling a complete edit of the picture from what had already been photographed and padding the film out with footage from the original The Hills Have Eyes.

In his 1998 book about Wes Craven, John Kenneth Muir states that The Hills Have Eyes, Part II repeats many of the narrative beats of the original The Hills Have Eyes though lacks ‘much of the style and verve that made the original so memorable’ (Muir, 1998: 102). Muir compares the picture to the sequels to Friday the 13th (Sean S Cunningham, 1980), inasmuch as the young characters in The Hills Have Eyes, Part II are, like the teenagers in the Friday the 13th sequels, largely sympathetic though unmemorable and essentially conforming to the stereotypes associated with the majority of post-Halloween (John Carpenter, 1978) slasher pictures (which the original The Hills Have Eyes predated). Muir notes that this separates the sequel from The Hills Have Eyes, which had a more rounded approach to characterisation, and he observes that with Scream (1996) Craven would satirise the kinds of ‘flat’, cookie-cutter characters associated with the bulk of 1980s slasher pictures and which populate The Hills Have Eyes, Part II (see ibid.). Muir also observes that The Hills Have Eyes, Part II is a weaker film than the original The Hills Have Eyes because it forgets that the first film was equally about ‘landscape as it was about the interesting characters’: it engendered a sense of dread by opening in the desert, with the characters being vulnerable from the get-go because they were fish out of water, whereas The Hills Have Eyes, Part II begins in suburbia where its protagonists are on home turf (ibid.). Muir suggests this would be less of a ‘problem’, in a narrative sense, if these characters were more richly developed (ibid.). In his 1998 book about Wes Craven, John Kenneth Muir states that The Hills Have Eyes, Part II repeats many of the narrative beats of the original The Hills Have Eyes though lacks ‘much of the style and verve that made the original so memorable’ (Muir, 1998: 102). Muir compares the picture to the sequels to Friday the 13th (Sean S Cunningham, 1980), inasmuch as the young characters in The Hills Have Eyes, Part II are, like the teenagers in the Friday the 13th sequels, largely sympathetic though unmemorable and essentially conforming to the stereotypes associated with the majority of post-Halloween (John Carpenter, 1978) slasher pictures (which the original The Hills Have Eyes predated). Muir notes that this separates the sequel from The Hills Have Eyes, which had a more rounded approach to characterisation, and he observes that with Scream (1996) Craven would satirise the kinds of ‘flat’, cookie-cutter characters associated with the bulk of 1980s slasher pictures and which populate The Hills Have Eyes, Part II (see ibid.). Muir also observes that The Hills Have Eyes, Part II is a weaker film than the original The Hills Have Eyes because it forgets that the first film was equally about ‘landscape as it was about the interesting characters’: it engendered a sense of dread by opening in the desert, with the characters being vulnerable from the get-go because they were fish out of water, whereas The Hills Have Eyes, Part II begins in suburbia where its protagonists are on home turf (ibid.). Muir suggests this would be less of a ‘problem’, in a narrative sense, if these characters were more richly developed (ibid.).

The Hills Have Eyes, Part II has some interesting and glaring similarities with Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986) - which is itself a largely derided 1980s-era sequel to a highly-regarded 1970s horror picture. The Hills Have Eyes, Part II was released two years prior to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, but both Hooper and Craven were, at this point in their respective careers, burdened with both the expectations set in place by a near-iconic horror film they had made a decade or so prior and audience demands that had shifted following the popularity of the slasher movies produced in the wake of Halloween. Both The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Hooper, 1974) and Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes have been seen as proto-slasher films, and in both cases the sequels were hampered by the manner in which they referred, and conformed, to the expectations that had been set in place by the slasher films that had become popular in the years between the release of the first picture and the production of the sequel. Most noticeably, both The Hills Have Eyes, Part II and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 open with a slow title scrawl that outlines the events of the first picture, also narrated by a male voice, both positing these events as based in fact and almost transforming them into myth through poetic language. (‘The following film is based in fact’, begins the scrawl that opens The Hills Have Eyes, Part II; ‘And of those who survive, none can forget that far out in the unmapped desert, beyond the towns and roads, the hills still have eyes’.) Equally noticeable even to casual viewers is the fact that both films build towards a climax in which the protagonist must face off against the film’s chief antagonist in an underground complex that, its original purpose now redundant, functions essentially as a charnel house. (In The Hills Have Eyes, Part II, this is a former mine shaft in which The Reaper and Pluto have been dumping the bodies of their victims; in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, it is a network of caves beneath the Texas Battleland Amusement Park that the Sawyers have decorated with skeletons and festering corpses.) The Hills Have Eyes, Part II has some interesting and glaring similarities with Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986) - which is itself a largely derided 1980s-era sequel to a highly-regarded 1970s horror picture. The Hills Have Eyes, Part II was released two years prior to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, but both Hooper and Craven were, at this point in their respective careers, burdened with both the expectations set in place by a near-iconic horror film they had made a decade or so prior and audience demands that had shifted following the popularity of the slasher movies produced in the wake of Halloween. Both The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Hooper, 1974) and Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes have been seen as proto-slasher films, and in both cases the sequels were hampered by the manner in which they referred, and conformed, to the expectations that had been set in place by the slasher films that had become popular in the years between the release of the first picture and the production of the sequel. Most noticeably, both The Hills Have Eyes, Part II and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 open with a slow title scrawl that outlines the events of the first picture, also narrated by a male voice, both positing these events as based in fact and almost transforming them into myth through poetic language. (‘The following film is based in fact’, begins the scrawl that opens The Hills Have Eyes, Part II; ‘And of those who survive, none can forget that far out in the unmapped desert, beyond the towns and roads, the hills still have eyes’.) Equally noticeable even to casual viewers is the fact that both films build towards a climax in which the protagonist must face off against the film’s chief antagonist in an underground complex that, its original purpose now redundant, functions essentially as a charnel house. (In The Hills Have Eyes, Part II, this is a former mine shaft in which The Reaper and Pluto have been dumping the bodies of their victims; in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, it is a network of caves beneath the Texas Battleland Amusement Park that the Sawyers have decorated with skeletons and festering corpses.)

Like several of Craven’s films, including Last House on the Left and the original The Hills Have Eyes (not to mention The People Under the Stairs, 1991), The Hills Have Eyes, Part II juxtaposes society with its opposite: in The Hills Have Eyes, this contrast was more marked in terms of a ‘good’ (ie, normative) family being pitted against a ‘bad’ (deviant/cannibalistic) family. Here, the fraternity of the young motocross riders is placed in relief by the twisted familial relationships of The Reaper and Pluto – uncle and nephew. ‘Straight’ society is thus contrasted with, and confronted by, its ‘other’, with the former employing all its resources – including transgressing the moral codes that define it – in order to contain the latter. In Last House on the Left, of course, Mari’s parents discover depths of hitherto unknown savagery in order to dispatch Krug’s group of bandits, who have murdered their daughter; during the climax of The Hills Have Eyes, the ‘good’ family display remarkable ingenuity and descend to depths they never thought possible (including using the corpse of their mother to lure the villains to their doom) in order to quell the threat represented by the cannibals. The original The Hills Have Eyes functioned as a vague allegory for American involvement in the war in Vietnam, Jupiter’s cannibalistic family standing in for the Viet Cong; in The Hills Have Eyes, Part II, The Reaper and Pluto continue to use similar guerrilla-style tactics in their conflict with the young people. Not long after the group of motocross riders arrive at the mine head, Pluto stages a distraction that allows him to sneak into the camp and steal one of the motocross bikes, luring Harry and Roy away from the others into a series of traps. Again, the films seems to be attempting to draw parallels between its story and the Vietnam war. As the film reaches its resolution, Cass and Roy devise a similarly ingenious trap for The Reaper, though unlike the first film, Craven doesn’t undercut their victory with a questioning of the level of violence employed by the film’ heroes: there is no moral ambiguity within Cass and Roy’s defeat of The Reaper, the film suggesting, like many contemporaneous slasher pictures, that the villain gets the comeuppance he deserves. Like several of Craven’s films, including Last House on the Left and the original The Hills Have Eyes (not to mention The People Under the Stairs, 1991), The Hills Have Eyes, Part II juxtaposes society with its opposite: in The Hills Have Eyes, this contrast was more marked in terms of a ‘good’ (ie, normative) family being pitted against a ‘bad’ (deviant/cannibalistic) family. Here, the fraternity of the young motocross riders is placed in relief by the twisted familial relationships of The Reaper and Pluto – uncle and nephew. ‘Straight’ society is thus contrasted with, and confronted by, its ‘other’, with the former employing all its resources – including transgressing the moral codes that define it – in order to contain the latter. In Last House on the Left, of course, Mari’s parents discover depths of hitherto unknown savagery in order to dispatch Krug’s group of bandits, who have murdered their daughter; during the climax of The Hills Have Eyes, the ‘good’ family display remarkable ingenuity and descend to depths they never thought possible (including using the corpse of their mother to lure the villains to their doom) in order to quell the threat represented by the cannibals. The original The Hills Have Eyes functioned as a vague allegory for American involvement in the war in Vietnam, Jupiter’s cannibalistic family standing in for the Viet Cong; in The Hills Have Eyes, Part II, The Reaper and Pluto continue to use similar guerrilla-style tactics in their conflict with the young people. Not long after the group of motocross riders arrive at the mine head, Pluto stages a distraction that allows him to sneak into the camp and steal one of the motocross bikes, luring Harry and Roy away from the others into a series of traps. Again, the films seems to be attempting to draw parallels between its story and the Vietnam war. As the film reaches its resolution, Cass and Roy devise a similarly ingenious trap for The Reaper, though unlike the first film, Craven doesn’t undercut their victory with a questioning of the level of violence employed by the film’ heroes: there is no moral ambiguity within Cass and Roy’s defeat of The Reaper, the film suggesting, like many contemporaneous slasher pictures, that the villain gets the comeuppance he deserves.

>The Hills Have Eyes, Part II opens promisingly enough with a scene in which Bobby, struggling with the trauma of the events depicted in the first film, is speaking with his psychiatrist. ‘You know he’s dead’, Bobby’s psychiatrist tells him in reference to Jupiter, ‘You killed him. You blew him to shit. Your sister axed him. Now, what does it take to convince you? [….] He was a stupid psychopath. You were able to trick him and kill him. They all were. They were all beatable and you did it. You know it’. Photographed with expressive chiaroscuro lighting, this scene outlines the premise of the main narrative of The Hills Have Eyes, Part II: the group of motocross racers with whom Bobby works are journeying to a competition where they will utilise Bobby’s new super-fuel formula, with the expectation that once word spreads vis-à-vis the potency of Bobby’s formula, a major fuel company will want to purchase it. However, as Bobby explains to his psychiatrist, the idea of passing through the desert fills him with anxiety, and as the group prepare to leave in the red coach that they use to transport their bikes (with presumably unintentional shades of Peter Yates’ 1963 film Summer Holiday in their choice of transportation) Bobby suffers a crippling panic attack and decides not to go. During Bobby’s conversation with the psychiatrist, antiquated rippled dissolves are used to take the viewer into the past, via extensive clips from the first film. Later in the picture, Ruby also has some long flashbacks to the events depicted in The Hills Have Eyes, as – infamously – does Beast. (For many viewers, one of the most memorable aspects of The Hills Have Eyes, Part II is the fact that the dog has a flashback.) >The Hills Have Eyes, Part II opens promisingly enough with a scene in which Bobby, struggling with the trauma of the events depicted in the first film, is speaking with his psychiatrist. ‘You know he’s dead’, Bobby’s psychiatrist tells him in reference to Jupiter, ‘You killed him. You blew him to shit. Your sister axed him. Now, what does it take to convince you? [….] He was a stupid psychopath. You were able to trick him and kill him. They all were. They were all beatable and you did it. You know it’. Photographed with expressive chiaroscuro lighting, this scene outlines the premise of the main narrative of The Hills Have Eyes, Part II: the group of motocross racers with whom Bobby works are journeying to a competition where they will utilise Bobby’s new super-fuel formula, with the expectation that once word spreads vis-à-vis the potency of Bobby’s formula, a major fuel company will want to purchase it. However, as Bobby explains to his psychiatrist, the idea of passing through the desert fills him with anxiety, and as the group prepare to leave in the red coach that they use to transport their bikes (with presumably unintentional shades of Peter Yates’ 1963 film Summer Holiday in their choice of transportation) Bobby suffers a crippling panic attack and decides not to go. During Bobby’s conversation with the psychiatrist, antiquated rippled dissolves are used to take the viewer into the past, via extensive clips from the first film. Later in the picture, Ruby also has some long flashbacks to the events depicted in The Hills Have Eyes, as – infamously – does Beast. (For many viewers, one of the most memorable aspects of The Hills Have Eyes, Part II is the fact that the dog has a flashback.)

As The Hills Have Eyes, Part II opens, Ruby has been rehabilitated and is now living a civilian life, working with Bobby, as ‘Rachel’. At one point, Ruby demonstrates some of the skills she acquired in her former life, sniffing the air whilst she and Hulk explore one of the mine buildings and Beast barks at something in the loftspace. ‘It’s a raccoon’, Ruby asserts. ‘You smell it?’, a disbelieving Hulk asks. ‘No, I just know how Beast barks when he finds one’, Ruby bluffs. When, passing by the area where the events in the first film occurred, the group of bike racers mock the story of Jupiter’s cannibalistic clan, they try to recollect the name of Jupiter’s daughter – Ruby – though are completely unaware that she is sitting on the bus with them: the gulf between ‘straight’ society and the twisted cannibalistic group living in the hills, which in the first film is shown to parody the hierarchies of Bobby’s ‘normal’ family, seems so great that the young people on the bus disbelieve the stories of Jupiter and the others. It has become more like a folk tale or myth than reportage or testimonial. When their bus becomes trapped in the desert, however, they are faced by Pluto and The Reaper and forced to accept the story of Jupiter’s clan as reality; unfortunately, this aspect of the narrative is frustratingly underdeveloped, the script sidestepping any sense of engagement with the rich potential of this premise in favour of finding ludicrous excuses to separate the young people from one another so that they may become more vulnerable. For example, even though they are becoming aware of the dangers presented by Pluto and The Reaper, Sue and Foster sneak away from the main group to engage in coitus on the bus; and shortly afterwards, Jane and Cass explore the mine buildings and discover a shower, Jane urging Cass to leave her alone so that she may use it. As The Hills Have Eyes, Part II opens, Ruby has been rehabilitated and is now living a civilian life, working with Bobby, as ‘Rachel’. At one point, Ruby demonstrates some of the skills she acquired in her former life, sniffing the air whilst she and Hulk explore one of the mine buildings and Beast barks at something in the loftspace. ‘It’s a raccoon’, Ruby asserts. ‘You smell it?’, a disbelieving Hulk asks. ‘No, I just know how Beast barks when he finds one’, Ruby bluffs. When, passing by the area where the events in the first film occurred, the group of bike racers mock the story of Jupiter’s cannibalistic clan, they try to recollect the name of Jupiter’s daughter – Ruby – though are completely unaware that she is sitting on the bus with them: the gulf between ‘straight’ society and the twisted cannibalistic group living in the hills, which in the first film is shown to parody the hierarchies of Bobby’s ‘normal’ family, seems so great that the young people on the bus disbelieve the stories of Jupiter and the others. It has become more like a folk tale or myth than reportage or testimonial. When their bus becomes trapped in the desert, however, they are faced by Pluto and The Reaper and forced to accept the story of Jupiter’s clan as reality; unfortunately, this aspect of the narrative is frustratingly underdeveloped, the script sidestepping any sense of engagement with the rich potential of this premise in favour of finding ludicrous excuses to separate the young people from one another so that they may become more vulnerable. For example, even though they are becoming aware of the dangers presented by Pluto and The Reaper, Sue and Foster sneak away from the main group to engage in coitus on the bus; and shortly afterwards, Jane and Cass explore the mine buildings and discover a shower, Jane urging Cass to leave her alone so that she may use it.

Video

The Hills Have Eyes, Part II is presented uncut, with a running time of 90:09 mins. Taking up approximately 25Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec; the presentation is billed as being a new 2k restoration from unspecified ‘original film elements’. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The Hills Have Eyes, Part II is presented uncut, with a running time of 90:09 mins. Taking up approximately 25Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec; the presentation is billed as being a new 2k restoration from unspecified ‘original film elements’. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1.

The 35mm colour photography is carried well on this Blu-ray release. There is a good level of detail present throughout the film. Damage is limited to some vertical scratches here and there and cigarette burns are present towards the ends of individual reels. These scratches are black rather than white, indicating that the original film elements used as the basis for this presentation are positive in nature rather than the film’s negative. The largely pleasing contrast levels, with defined midtones and fairly subtly gradation into the toe, and the reasonably tight grain structure would suggest an interpositive or similar was used as the source for this HD presentation rather than a print. There is some minor ‘hotness’ in the highlights in various spots throughout the film but nothing too dramatic. The opening scene, in which Bobby’s conversation with his psychiatrist is focused with expressive chiaroscuro lighting, is carried very nicely here – bold shadows, accompanied by a subtly drop into the toe and rich midtones. Colour is naturalistic and consistent though skintones sometimes seem very slightly ‘hot’. Finally the encode to disc is unproblematic and ensures that the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film.

Some full-sized screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 track. This has depth and range, and dialogue is audible throughout, but it’s certainly not ‘showy’. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included. These accurately transcribe the film’s dialogue and are clear and readable throughout.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with The Hysteria Continues. The always-dependable, and always-entertaining, chaps of the slasher movie-focused The Hysteria Continues podcast explore The Hills Have Eyes, Part II. The group are quite open about the weaknesses of The Hills Have Eyes, Part II though are clearly fans of the film also, with some of the members suggesting that they enjoy this film more than the first The Hills Have Eyes – albeit with an admittance that the first picture is the better film of the two. They talk about the similarities in Manfredini’s score for this and Friday the 13th, Part III. They talk about the inconsistencies within Wes Craven’s career and the overlap, in terms of production, between this film and A Nightmare on Elm Street. The group also reflect on the casting of the film and some of the performances. It’s an excellent commentary, both informative and enthusiastic, with some strong contextualisation of this much-maligned picture. - ‘Blood, Sand and Fire’ (31:16). This superb documentary features input from Janus Blythe and Michael Berryman, the film’s producer Peter Locke, composer Harry Manfredini, production designer Dominick Bruno and production manager/assistant director John Callas. Locke talks about his response to Craven’s Last House on the Left, which led to Locke producing The Hills Have Eyes. Michael Berryman reflects on his association with Wes Craven, with whom Berryman worked on several films. Both Berryman and Manfredini discuss the impact the commercial failure of Swamp Thing had on Wes Craven (1982). The participant discuss Craven’s qualities as a filmmaker, Locke saying Craven was ‘a funny guy’ who ‘wouldn’t pressure anyone into doing anything’: Craven ‘would never yell at anyone’ on a set. - Still Gallery (6:52). - Trailer (2:44).

Overall

v  What is perhaps most frustrating about The Hills Have Eyes, Part II are the intriguing aspects of the story that remain frustratingly underdeveloped: Bobby’s struggle with the trauma of the events depicted in the first film, which goes nowhere because Bobby disappears from the film around 20 minutes into its running time; the blind Cass has subtly psychic powers and amplified sense of smell and hearing, but the film does virtually nothing with this. That said, as long as one enters into it with reasonable expectations, The Hills Have Eyes, Part II is a fairly entertaining film and one that has certainly been enjoyed ironically by many. While a film with some noticeable faults, it’s arguably far from Craven’s worst picture. The presentation of The Hills Have Eyes, Part II on Arrow Video’s new Blu-ray release is pretty good, certainly an improvement over the film’s previous DVD releases, though would seem to be based on a positive source. The main feature is accompanied by an excellent commentary from The Hysteria Continues group and a fascinating documentary which helps to contextualise the film and explore its position in Wes Craven’s body of work; listening to the participants talk so warmly about Craven, one is reminded how much of a loss his fairly recent passing (in 2015) was to the world of horror filmmaking. What is perhaps most frustrating about The Hills Have Eyes, Part II are the intriguing aspects of the story that remain frustratingly underdeveloped: Bobby’s struggle with the trauma of the events depicted in the first film, which goes nowhere because Bobby disappears from the film around 20 minutes into its running time; the blind Cass has subtly psychic powers and amplified sense of smell and hearing, but the film does virtually nothing with this. That said, as long as one enters into it with reasonable expectations, The Hills Have Eyes, Part II is a fairly entertaining film and one that has certainly been enjoyed ironically by many. While a film with some noticeable faults, it’s arguably far from Craven’s worst picture. The presentation of The Hills Have Eyes, Part II on Arrow Video’s new Blu-ray release is pretty good, certainly an improvement over the film’s previous DVD releases, though would seem to be based on a positive source. The main feature is accompanied by an excellent commentary from The Hysteria Continues group and a fascinating documentary which helps to contextualise the film and explore its position in Wes Craven’s body of work; listening to the participants talk so warmly about Craven, one is reminded how much of a loss his fairly recent passing (in 2015) was to the world of horror filmmaking.

References: Muir, John Kenneth, 1998: Wes Craven: The Art of Horror. London: McFarland & Company Please click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|