|

|

The Film

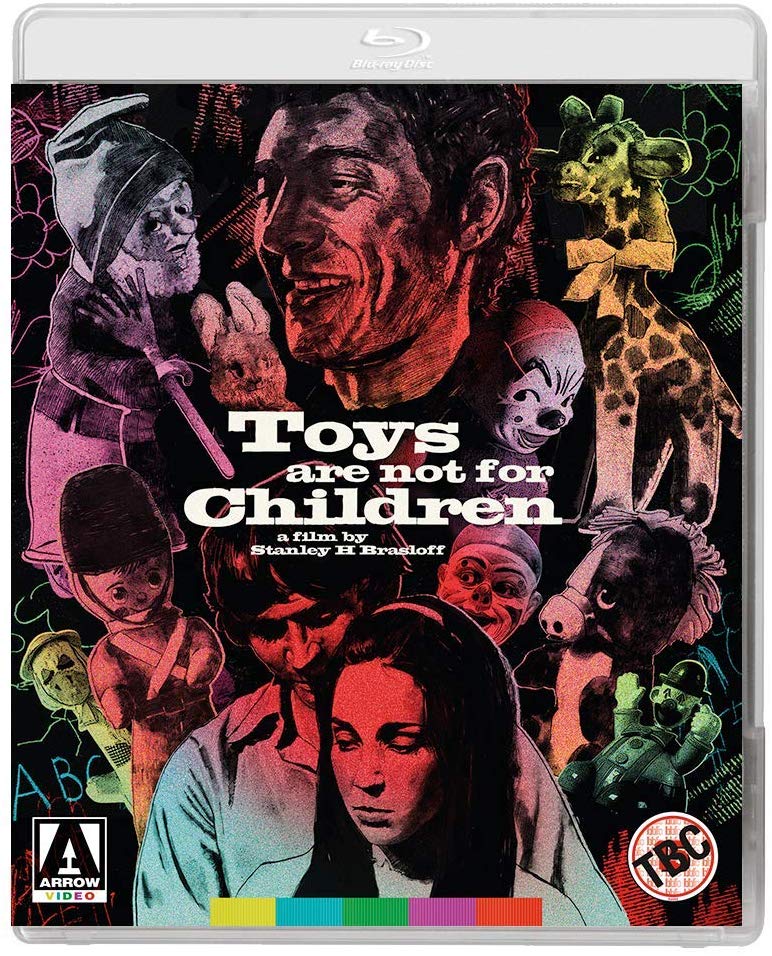

Toys are Not for Children (Stanley Brasloff, 1972) Toys are Not for Children (Stanley Brasloff, 1972)

Synopsis: Twenty year old Jamie Godard (Marcia Forbes) lives with her shrill harridan of a mother Edna (Fran Warren), Jamie’s father Philip (Peter Lightstone) having left the family when Jamie was a child. Jamie has an idealised image of her father, which Edna tries to demolish at every opportunity, telling her daughter that Philip cavorted with prostitutes. However, since Jamie was a small child, Philip has sent her toys; Jamie has kept these gifts, playing with her toys into adulthood. Jamie works at a toy shop owned by Max Gunther (N J Osrag). One day at work, Jamie meets a middle-aged woman, Pearl Valdi (Evelyn Kingsley), who claims to know Jamie’s father. Pearl tells Jamie her address in New York City, inviting Jamie to come over. However, Jamie is unaware that Pearl is a prostitute, and when Jamie arrives at the address Pearl gave her, she is met by Pearl’s sleazy pimp, Eddie (Luis Arroyo). Eddie attempts to rape Jamie but is stopped by Pearl. Returning home, Jamie tells Edna of her meeting with Pearl and Eddie’s attempt to rape her. Edna responds in anger, telling Jamie that ‘I tried so hard, so you woudn’t end up like her [Pearl], a painted pig!’ Edna kicks Jamie out of the family home. Jamie marries her colleague Charlie Belmond (Harlan Cary Poe), and Charlie is shocked by how many toys Jamie fills their home with. When Charlie attempts to seduce his new bride on their wedding night, Jamie resists his advances, choosing instead to watch television, placing one of her toys on the marital bed between herself and her husband. Soon, Charlie is frequenting the local nightclubs, picking up women and having sex with them – something which is noticed by an appalled Max on a night out. As Jamie and Charlie’s relationship disintegrates, Jamie spends more and more time with Pearl, eventually becoming aware that Pearl knows Jamie’s father…  Critique: An exploitative little film which is as much influenced by the narrative styles of European art cinema as the sensationalistic material of American exploitation filmmaking, Stanley Brasloff’s Toys are Not for Children (1972) is dominated by non-linear storytelling: Jamie’s experiences in the diegetic present are frequently fragmented by fleeting flashbacks, some only a second or two in length, to her childhood; these moments of analepsis are often bridged by lines of dialogue that connect the past and present. Communicating the sense that Jamie is forever carrying her past with her, the overall effect seems to suggest the influence of films like Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad (1961) or, particularly in terms of its shared focus on psychological disintegration and femininity, Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966). Critique: An exploitative little film which is as much influenced by the narrative styles of European art cinema as the sensationalistic material of American exploitation filmmaking, Stanley Brasloff’s Toys are Not for Children (1972) is dominated by non-linear storytelling: Jamie’s experiences in the diegetic present are frequently fragmented by fleeting flashbacks, some only a second or two in length, to her childhood; these moments of analepsis are often bridged by lines of dialogue that connect the past and present. Communicating the sense that Jamie is forever carrying her past with her, the overall effect seems to suggest the influence of films like Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad (1961) or, particularly in terms of its shared focus on psychological disintegration and femininity, Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966).

Though less concerned with nudity, Brasloff’s nonetheless undeniably sleazy film is comparable to some of Spanish filmmaker Jess Franco’s pictures of the same era, which often dealt with themes of incestuous desire – such as Eugenie (1973) and Al otro lado del espejo (The Other Side of the Mirror, 1973). Opening with an adult Jamie lying naked on her bed, grinding against her body the stuffed toy soldier her father bought her as a child whilst groaning ‘Daddy! Daddy!’ orgasmically, Toys are Not for Children doesn’t shy away from controversy in its examination of the Electra complex. Jamie’s moment of sexual ecstasy which opens the film is almost instantaneously interrupted by the appearance of her mother, Edna, who enters the bedroom and chastises Jamie for her behaviour. As soon as Edna appears, she is marked as a harridan, asserting through clenched teeth that Jamie is as ridden with sin as her father, Philip: ‘How long has this been going on?’, Edna rages, ‘You’re just like your father! Well, he’s too busy with his women. All he ever did was send you these stinking toys, and you’d take them to bed. It’s unnatural! [….] He’s not a man. He’s a snake. All I ever wanted you to do was love me. Just a little [….] Your father is with his whores’. Later in the film, Edna’s words are echoed by Charlie, who questions Jamie’s attachment to her toys and asks, after Jamie has refused to have sex with him, ‘Why can’t you love me?’  Throughout the picture, Edna belittles Jamie’s father openly, her assertions about his association with prostitutes contrasting with Jamie’s idealised memories of him. In the flashbacks, Philip appears to be a caring parent, playing lovingly with his young daughter and tucking her into bed for the night. Throughout much of the film, it seems fairly easy to see which Philip might have left Edna, who is bitter and spiteful. However, as the narrative progresses Jamie hears negative stories about Philip from Pearl too, Pearl describing Philip as ‘a no good bastard [….] He’d ruin her [Jamie]’. As the film draws to its climax Pearl, whose sapphic attentions have been spurned by a shocked Jamie, arranges a meeting between Jamie and her father – without telling Philip that Jamie is his daughter and not a prostitute – out of spite. This of course leads to Philip’s naïve seduction of Jamie, though even here – and with consideration that Philip isn’t aware the adult Jamie is his daughter – one might wonder what is so deviant about Philip as to make Pearl wary of him. Where for much of the film’s running time, the viewer might struggle to reconcile Edna and Pearl’s denouncements of Philip’s behaviour with the evidence of a loving father that seems to be presented in the flashbacks, Philip’s admittedly naïve seduction of Jamie at the climax of the film seems to retroactively cast these flashbacks in a very different light. Certainly, however, Philip is outwardly less perverse than Eddie, who attempts to rape Jamie and also confesses that he has ‘a thing for virgins’. In actuality, Philip is also arguably less perverse than Pearl, who takes Jamie under her wing and mothers her – but harbours sexual feelings for the young woman whom she has taken as her charge, resulting in a clumsy attempt to seduce Jamie. In a moment of epiphany, Jamie reacts negatively to Pearl’s attempt to seduce her, observing angrily that Pearl is ‘the same as everybody else’ – in other words, interested in nothing but sexual congress with Jamie. Throughout the picture, Edna belittles Jamie’s father openly, her assertions about his association with prostitutes contrasting with Jamie’s idealised memories of him. In the flashbacks, Philip appears to be a caring parent, playing lovingly with his young daughter and tucking her into bed for the night. Throughout much of the film, it seems fairly easy to see which Philip might have left Edna, who is bitter and spiteful. However, as the narrative progresses Jamie hears negative stories about Philip from Pearl too, Pearl describing Philip as ‘a no good bastard [….] He’d ruin her [Jamie]’. As the film draws to its climax Pearl, whose sapphic attentions have been spurned by a shocked Jamie, arranges a meeting between Jamie and her father – without telling Philip that Jamie is his daughter and not a prostitute – out of spite. This of course leads to Philip’s naïve seduction of Jamie, though even here – and with consideration that Philip isn’t aware the adult Jamie is his daughter – one might wonder what is so deviant about Philip as to make Pearl wary of him. Where for much of the film’s running time, the viewer might struggle to reconcile Edna and Pearl’s denouncements of Philip’s behaviour with the evidence of a loving father that seems to be presented in the flashbacks, Philip’s admittedly naïve seduction of Jamie at the climax of the film seems to retroactively cast these flashbacks in a very different light. Certainly, however, Philip is outwardly less perverse than Eddie, who attempts to rape Jamie and also confesses that he has ‘a thing for virgins’. In actuality, Philip is also arguably less perverse than Pearl, who takes Jamie under her wing and mothers her – but harbours sexual feelings for the young woman whom she has taken as her charge, resulting in a clumsy attempt to seduce Jamie. In a moment of epiphany, Jamie reacts negatively to Pearl’s attempt to seduce her, observing angrily that Pearl is ‘the same as everybody else’ – in other words, interested in nothing but sexual congress with Jamie.

Eddie’s aforementioned attempt to rape Jamie is thwarted when Pearl arrives home, chiding Eddie and consoling Pearl. However, later in the film, Jamie returns to Eddie with a clear desire for him to seduce her. Eddie quickly cottons on to Jamie’s needs: as he roughly presses himself against her, he observes that she ‘want[s] me to take you so your daddy can’t blame you for what you did’. ‘This kind of life excites you’, Eddie observes, ‘Me and Pearl, what we do. It’s what your father likes [….] I think you want something from me. You want me to make love to you, so you can tell your father it wasn’t your fault [….] I’m not your husband. You can’t stop me’. ‘Force me’, she responds. Eddie reasons that Jamie wants to be forced into her first sex act so that she can avoid accepting ‘blame’ for her involvement in it. Following Eddie’s ‘turning out’ of Jamie, Jamie starts turning tricks with johns, role play becoming an integral part of her ‘act’. She approaches this with utter naivete, excitedly exclaiming to Pearl that Eddie is sending her (Jamie) on ‘my first job’: ‘I want to be like you’, she cheerfully tells a horrified Pearl. Eddie’s aforementioned attempt to rape Jamie is thwarted when Pearl arrives home, chiding Eddie and consoling Pearl. However, later in the film, Jamie returns to Eddie with a clear desire for him to seduce her. Eddie quickly cottons on to Jamie’s needs: as he roughly presses himself against her, he observes that she ‘want[s] me to take you so your daddy can’t blame you for what you did’. ‘This kind of life excites you’, Eddie observes, ‘Me and Pearl, what we do. It’s what your father likes [….] I think you want something from me. You want me to make love to you, so you can tell your father it wasn’t your fault [….] I’m not your husband. You can’t stop me’. ‘Force me’, she responds. Eddie reasons that Jamie wants to be forced into her first sex act so that she can avoid accepting ‘blame’ for her involvement in it. Following Eddie’s ‘turning out’ of Jamie, Jamie starts turning tricks with johns, role play becoming an integral part of her ‘act’. She approaches this with utter naivete, excitedly exclaiming to Pearl that Eddie is sending her (Jamie) on ‘my first job’: ‘I want to be like you’, she cheerfully tells a horrified Pearl.

Fundamentally, Toys are Not for Children recycles and foregrounds the Madonna-Whore dichotomy that can be found at the heart of so many Hollywood films, though here the distinction between ‘pure’ and ‘impure’ femininity is underscored much more than it was in many classic films noir, for example, which buried a similar theme in their subtext. Jamie is an innocent, playing with her toys rather than sleeping with her new husband Charlie, though she is also drawn to the sleazy lifestyles of Pearl and Eddie: in other words, Jamie is torn between the righteous repression of her mother (Edna) and the sexual licentiousness of her father (Philip). When Jamie marries Charlie and resists his attempts to have sex with her, Charlie repeats the pattern set by Jamie’s father, visiting the city to find ‘loose’ women who will sleep with him. (‘She’s sick, Max, sick!’, Jamie tells Max when Max sees him in the nightclub, ‘I need to get laid!’) The film does not explore the nature/nurture debate with any sense of depth but within the narrative, there’s a strong undercurrent of suggestion that behaviour is inherited through one’s parents as if it is part of one’s genetic coding, patterns of behaviour spiralling into the future and destroying any hope for growth. Jamie’s future, the film seems to suggest, was blighted from her earliest days because of the incompatibility of her parents’ attitudes towards sex – and because of the departure of her father from the family unit, which led to Jamie becoming fixated at a certain, sexually naïve, stage of development. This has led, the film posits, to Jamie being stuck at a stage of development in which sex and play have become confused – and the role of father and ‘daddy’ (as in, a sexually dominant partner) are interchangeable. Fundamentally, Toys are Not for Children recycles and foregrounds the Madonna-Whore dichotomy that can be found at the heart of so many Hollywood films, though here the distinction between ‘pure’ and ‘impure’ femininity is underscored much more than it was in many classic films noir, for example, which buried a similar theme in their subtext. Jamie is an innocent, playing with her toys rather than sleeping with her new husband Charlie, though she is also drawn to the sleazy lifestyles of Pearl and Eddie: in other words, Jamie is torn between the righteous repression of her mother (Edna) and the sexual licentiousness of her father (Philip). When Jamie marries Charlie and resists his attempts to have sex with her, Charlie repeats the pattern set by Jamie’s father, visiting the city to find ‘loose’ women who will sleep with him. (‘She’s sick, Max, sick!’, Jamie tells Max when Max sees him in the nightclub, ‘I need to get laid!’) The film does not explore the nature/nurture debate with any sense of depth but within the narrative, there’s a strong undercurrent of suggestion that behaviour is inherited through one’s parents as if it is part of one’s genetic coding, patterns of behaviour spiralling into the future and destroying any hope for growth. Jamie’s future, the film seems to suggest, was blighted from her earliest days because of the incompatibility of her parents’ attitudes towards sex – and because of the departure of her father from the family unit, which led to Jamie becoming fixated at a certain, sexually naïve, stage of development. This has led, the film posits, to Jamie being stuck at a stage of development in which sex and play have become confused – and the role of father and ‘daddy’ (as in, a sexually dominant partner) are interchangeable.

Video

Photographed on 35mm colour stock, Toys are Not for Children is handsomely presented on Arrow’s new Blu-ray release. Presented in 1080p using the AVC codec, Arrow’s presentation of Toys are Not for Children fills slightly over 24.2Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc and is in the 1.78:1 ratio, which is near-as-dammit to 1.85:1 (which presumably was the screen ratio of the film’s theatrical release in the US). The film is uncut, with a running time of 85:06 mins. Photographed on 35mm colour stock, Toys are Not for Children is handsomely presented on Arrow’s new Blu-ray release. Presented in 1080p using the AVC codec, Arrow’s presentation of Toys are Not for Children fills slightly over 24.2Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc and is in the 1.78:1 ratio, which is near-as-dammit to 1.85:1 (which presumably was the screen ratio of the film’s theatrical release in the US). The film is uncut, with a running time of 85:06 mins.

Though there is some audacious editing on display throughout the picture, the photography is quite ‘flat’ and television-like albeit interspersed with some punctive, very tight close-ups of the actors’ faces. That said, this HD presentation is very good. The opening titles, optically-printed, are in rough shape, but the bulk of the picture looks excellent. A rich level of visual detail is present throughout the film, and damage is limited to a few vertical scratches and the odd white fleck or speck – indicating debris on the film’s negative. Contrast levels are good, with richly defined midtones dominating the presentation, complemented by a balanced shoulder and a subtle drop-off into the toe – where the blacks are rich and deep. Colours are bold and vivid, yet naturalistic in terms of skintones. The encode to disc is pleasing, retaining the structure of 35mm film. Full-sized screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 track. This is far from ‘showy’ but is rich and deep, dialogue being audible throughout. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included. These are accurate in transcribing the dialogue and easy to read.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary by Kat Ellinger and Heather Drain. Podcasters Ellinger and Drain offer a commentary to Toys are Not for Children that is perhaps a little hyperbolic in terms of its praise for the picture, but which nevertheless makes some very valid points about Brasloff’s apparent arthouse aspirations (or pretensions, depending on how one looks at it). It’s a lively commentary, the two participants clearly having a lot of fun talking about the picture. They talk about the association of men with a resistance to marriage and suggest that Toys are Not for Children is somewhat original in reversing this paradigm, though this is perhaps an outgrowth of the picture’s position in terms of the then-burgeoning women’s lib movement. (Notably, Carly Simon’s ‘That’s the Way I Always Heard it Should Be’, which contains a similarly anti-marriage sentiment from a female perspective, was released a year earlier, in 1971.) - ‘Fragments of Stanley H Brasloff’ (25:03). Stephen Thrower reflects on the position of Toys are Not for Children within the career of its director, Stanley H Brasloff – who directed no more than two films (and wrote another). Thrower considers Brasloff’s association with stage in theatre and stand-up comedy. Thrower talks about Behind Locked Doors, which Brasloff wrote in 1968, and Two Girls for a Madman, Brasloff’s directorial debut in the same year. Thrower reflects on Toys are Not for Children and its qualities, which he suggests shine despite the film not being both cheaply-shot and ‘psychologically penetrating’. - ‘“Dirty Dolls”: Femininity, Perversion and Play’ (23:00). This video essay by Alexandra Heller-Nicholas uses Toys are Not for Children as a springboard for a discussion of the manner in which femininity, and female sexuality, has been connected with concepts of play.  Heller-Nicholas begins by comparing Toys are Not for Children and Todd Haynes’ Carol (2015), adapted from Patricia Highsmith’s novel The Price of Salt (1952). Heller-Nicholas argues that toys are used as a metaphor for displaced female sexuality, and she considers the manner in which dolls generally are used to ‘train’ female children to develop their self-identity in ways that foreground the sexual ‘functions’ of adult women (eg, through the horrendous Barbie dolls). She also examines some of the ways in which filmmakers have connected female sexuality with play and childhood – for example, in some of the deeply unsettling-to-modern eyes ‘baby burlesque’ pictures which starred Shirley Temple and were famously ‘called out’ by Graham Greene during his time as a film critic for the Spectator. Heller-Nicholas’ examination of this issue is challenging but timely and well-considered. Heller-Nicholas begins by comparing Toys are Not for Children and Todd Haynes’ Carol (2015), adapted from Patricia Highsmith’s novel The Price of Salt (1952). Heller-Nicholas argues that toys are used as a metaphor for displaced female sexuality, and she considers the manner in which dolls generally are used to ‘train’ female children to develop their self-identity in ways that foreground the sexual ‘functions’ of adult women (eg, through the horrendous Barbie dolls). She also examines some of the ways in which filmmakers have connected female sexuality with play and childhood – for example, in some of the deeply unsettling-to-modern eyes ‘baby burlesque’ pictures which starred Shirley Temple and were famously ‘called out’ by Graham Greene during his time as a film critic for the Spectator. Heller-Nicholas’ examination of this issue is challenging but timely and well-considered.

- ‘Theme Song’ (2:33). The film’s main title theme plays out over a still frame of the film’s title. - Stanley H Brasloff Trailer Gallery: Behind Locked Doors (1968) (3:57); Two Girls for a Madman (1968) (1:49); Toys are Not for Children (1972) (2:47).

Overall

An undeniably oddball film, Toys are Not for Children borrows as much from European art cinema as from the American exploitation film. The narrative has more than its fair share of off-kilter moments: not least among these is the revelation that though Charlie and Jamie are married, Charlie does not know the birthdate of his bride. (It’s unclear as to whether or not this is intentional – perhaps Brasloff is suggesting that the young Charlie and Jamie are both too naïve and self-absorbed to be married.) On the other hand, there is also some clever foreshadowing – such as when Charlie bemoans that ‘Half the time, I never even know you’re here. You just sit and don’t say anything. You never even look at me. It’s like you were dead!’ The line takes on a retrospective significance with events that unfold later in the story. An undeniably oddball film, Toys are Not for Children borrows as much from European art cinema as from the American exploitation film. The narrative has more than its fair share of off-kilter moments: not least among these is the revelation that though Charlie and Jamie are married, Charlie does not know the birthdate of his bride. (It’s unclear as to whether or not this is intentional – perhaps Brasloff is suggesting that the young Charlie and Jamie are both too naïve and self-absorbed to be married.) On the other hand, there is also some clever foreshadowing – such as when Charlie bemoans that ‘Half the time, I never even know you’re here. You just sit and don’t say anything. You never even look at me. It’s like you were dead!’ The line takes on a retrospective significance with events that unfold later in the story.

Arrow’s Blu-ray release of Toys are Not for Children is very good, grounded in a very pleasing presentation of the main feature that is supported by some interesting contextual material. Though these ‘extra’ features are noticeably devoid of input from any of the film’s personnel, they offer a satisfying insight into the picture – particularly Stephen Thrower’s comments about the film and Alexandra Heller-Nicholas’ video essay, which frames Toys are Not for Children within a wider discussion of the representation of female sexuality in American cinema. Please click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|