|

|

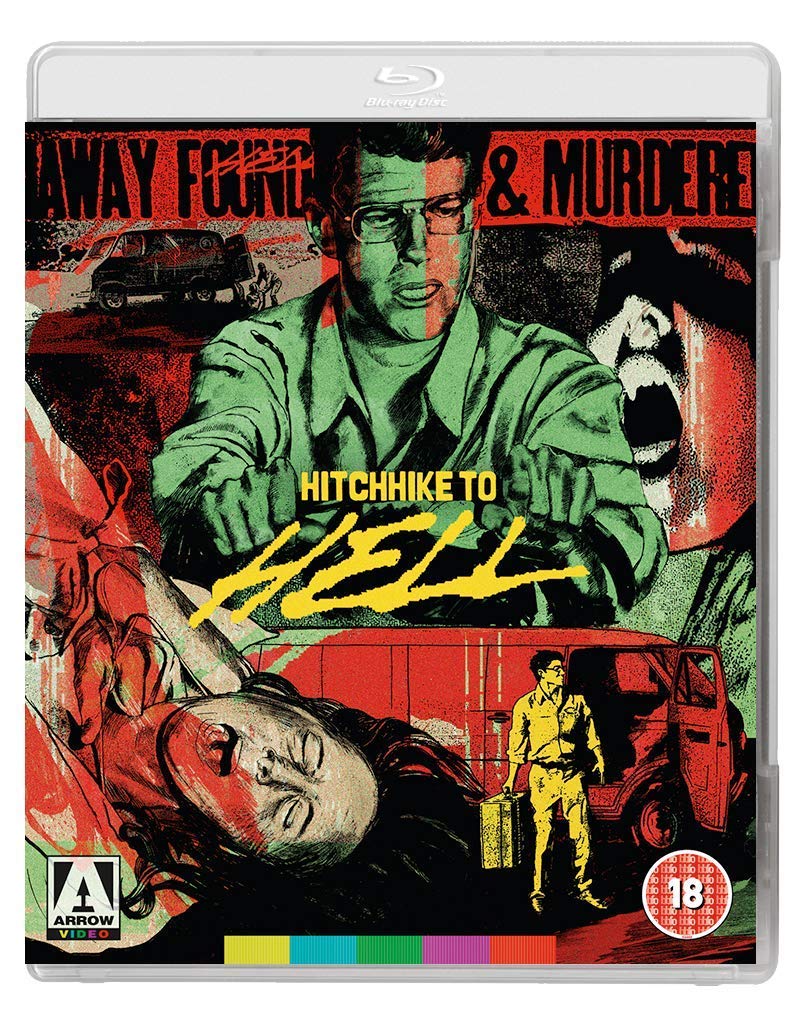

Hitch Hike to Hell (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (15th December 2019). |

|

The Film

Hitch Hike to Hell (Ive Berwick, 1977) Hitch Hike to Hell (Ive Berwick, 1977)

Synopsis: In Crescent City, quiet Howard Martin (Robert Gribbin), who lives with his mother (Dorothy Bennett), works for laundry owner Mr Baldwin (John Harmon). Howard drives a van, delivering and picking up customers’ laundry. As the film opens, Howard picks up a young female hitchhiker. However, discovering that she is a runaway who apparently hates her parents, Howard is driven into a rage, strangling the young woman with one of the wire hangers in his van before dumping her body by the roadside. Later, Howard has no recollection of the murder though experiences a fragmentary but vivid flashback when he reads a newspaper article about the discovery of the girl’s body. However, whilst driving the laundry van he soon picks up another hitchhiker, again murdering her when he discovers she is a runaway who expresses hatred towards her family. Meanwhile, two detectives – Captain Shaw (Russell Johnson) and Lieutenant Davis (Randy Echols) – become aware of the connections between the killings of hitchhikers, each murder throwing up new evidence. They race against time in an attempt to identify and apprehend the serial killer who is haunting their city.  Critique: Directed by Irv(in) Berwick, whose directorial debut had been the cult monster picture The Monster of Piedras Blancas (1959), Hitch Hike to Hell is loosely based on the misadventures of ‘Coed Killer’ Edmund Kemper and was originally released in the US in 1977, though appears to have been photographed a number of years earlier. (In the dialogue, Captain Shaw refers to ‘that nut down in Houston’ – presumably Dean Corll, the ‘Pied Piper’ who was shot dead by his accomplice, Elmer Henley, after murdering at least 27 boys and young men; Corll was killed in 1973, so presumably Hitch Hike to Hell was produced some time before his death.) Berwick’s picture anticipates some of the serial killer-themed movies (and other media) that would become more popular in the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s: like films such as Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (John McNaughton, 1986), Marvin J Chomsky’s The Deliberate Stranger (1986) and Joe D’Amato’s Buio Omega (Beyond the Darkness, 1981), or novels like James Ellroy’s Killer on the Road (1986), Hitch Hike to Hell depicts a very modern serial killer whose crimes revolve around the road and motor vehicles. Howard selects/victimises vulnerable young women: hitchhikers and runaways. The colour of the laundry van that Howard drives (bright red) seems all too symbolic. The vehicle itself seems to capture the very modern concept of the serial killer, though the notion of the ‘murder van’ would gain notoriety in the years after the production of Hitch Hike to Hell, thanks to the activities of the likes of Lawrence Bittaker and Roy Norris (the ‘Toolbox Killers’). Critique: Directed by Irv(in) Berwick, whose directorial debut had been the cult monster picture The Monster of Piedras Blancas (1959), Hitch Hike to Hell is loosely based on the misadventures of ‘Coed Killer’ Edmund Kemper and was originally released in the US in 1977, though appears to have been photographed a number of years earlier. (In the dialogue, Captain Shaw refers to ‘that nut down in Houston’ – presumably Dean Corll, the ‘Pied Piper’ who was shot dead by his accomplice, Elmer Henley, after murdering at least 27 boys and young men; Corll was killed in 1973, so presumably Hitch Hike to Hell was produced some time before his death.) Berwick’s picture anticipates some of the serial killer-themed movies (and other media) that would become more popular in the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s: like films such as Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (John McNaughton, 1986), Marvin J Chomsky’s The Deliberate Stranger (1986) and Joe D’Amato’s Buio Omega (Beyond the Darkness, 1981), or novels like James Ellroy’s Killer on the Road (1986), Hitch Hike to Hell depicts a very modern serial killer whose crimes revolve around the road and motor vehicles. Howard selects/victimises vulnerable young women: hitchhikers and runaways. The colour of the laundry van that Howard drives (bright red) seems all too symbolic. The vehicle itself seems to capture the very modern concept of the serial killer, though the notion of the ‘murder van’ would gain notoriety in the years after the production of Hitch Hike to Hell, thanks to the activities of the likes of Lawrence Bittaker and Roy Norris (the ‘Toolbox Killers’).

Though cack-handed in many ways, Hitch Hike to Hell has an eerie sense of realism in the scenes depicting the aftermath of Howard’s crimes. In particular, the positioning of the victims’ bodies, their limbs contorted and their clothing dishevelled, has a sense of verisimilitude to it that brings to mind John McNaughton’s tableau-like framing of Henry’s victims in Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. This, combined with the coldly objective framing of shots depicting Howard’s victims, suggests the filmmakers had studied modern forensic photographs of scenes of murder. (In fact, some of these shots have an eerie similarity to the colour forensic photographs of the Hillside Stranglers’ crime scenes, from later in the 1970s, than the monochromatic photographs of the victims of Edmund Kemper or the Boston Strangler, for example.) Also like other later serial killer pictures (excepting Henry), Hitch Hike to Hell juxtaposes the activities of its killer with the police manhunt; in contrasting Captain Shaw and Lieutenant Davis’ hunt for the killer with the actions of Howard, the film might be compared to Wes Craven’s roughly contemporaneous Last House on the Left (1972), which crosscuts between Krug’s (David Hess) gang’s abuse and murder of Mari and Phyllis, and the antics of the two bumbling police officers who are trying to track the gang down. However, unlike Last House on the Left, Hitch Hike to Hell doesn’t mock its officers of the law: Shaw and Davis are competent, sympathetic characters. Davis struggles with his work, which threatens his relationship with his wife; when Davis’ wife reveals she is pregnant, Davis responds with an expression of resignation rather than joy. He tells his despondent wife, ‘I was thinking that bringing a baby into this world may not be the best idea. I mean, look at all that’s going on. Rape, murder, drug addiction, war, poverty, all that. I mean, who wants a child to face such things?’ In another scene, Shaw and Davis are horrified when the parents of a young hitchhiker, Pam (Beth Reis), express absolute apathy as to the whereabouts of their daughter. When Pam’s parents refuse to come to Crescent City to collect Pam and bring her home safely, Shaw observes, ‘Seems there are delinquent parents out there as much as delinquent children’. Though cack-handed in many ways, Hitch Hike to Hell has an eerie sense of realism in the scenes depicting the aftermath of Howard’s crimes. In particular, the positioning of the victims’ bodies, their limbs contorted and their clothing dishevelled, has a sense of verisimilitude to it that brings to mind John McNaughton’s tableau-like framing of Henry’s victims in Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. This, combined with the coldly objective framing of shots depicting Howard’s victims, suggests the filmmakers had studied modern forensic photographs of scenes of murder. (In fact, some of these shots have an eerie similarity to the colour forensic photographs of the Hillside Stranglers’ crime scenes, from later in the 1970s, than the monochromatic photographs of the victims of Edmund Kemper or the Boston Strangler, for example.) Also like other later serial killer pictures (excepting Henry), Hitch Hike to Hell juxtaposes the activities of its killer with the police manhunt; in contrasting Captain Shaw and Lieutenant Davis’ hunt for the killer with the actions of Howard, the film might be compared to Wes Craven’s roughly contemporaneous Last House on the Left (1972), which crosscuts between Krug’s (David Hess) gang’s abuse and murder of Mari and Phyllis, and the antics of the two bumbling police officers who are trying to track the gang down. However, unlike Last House on the Left, Hitch Hike to Hell doesn’t mock its officers of the law: Shaw and Davis are competent, sympathetic characters. Davis struggles with his work, which threatens his relationship with his wife; when Davis’ wife reveals she is pregnant, Davis responds with an expression of resignation rather than joy. He tells his despondent wife, ‘I was thinking that bringing a baby into this world may not be the best idea. I mean, look at all that’s going on. Rape, murder, drug addiction, war, poverty, all that. I mean, who wants a child to face such things?’ In another scene, Shaw and Davis are horrified when the parents of a young hitchhiker, Pam (Beth Reis), express absolute apathy as to the whereabouts of their daughter. When Pam’s parents refuse to come to Crescent City to collect Pam and bring her home safely, Shaw observes, ‘Seems there are delinquent parents out there as much as delinquent children’.

Hitch Hike to Hell seems obviously to exist in the shadow of Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960): like so many post-Norman Bates serial killers, Howard has an unhealthy relationship with his other – which crosses the line from nurturing to smothering. In one scene, after a moment of psychological trauma, Howard climbs into bed with his mother, who coddles him like a baby. However, Howard is outwardly normal; Captain Shaw tells Pam’s parents that ‘He [the killer] isn’t wearing a sign around his neck’. Hitch Hike to Hell struggles to engage with the psychology of its killer, and where later serial killer pictures would often depict their protagonists in an manner laden with a (necessary) distancing irony, Hitch Hike to Hell manages to make Howard somewhat sympathetic. His murders are committed whilst Howard is in what can only be described as a dissociative fugue state that is triggered when Howard’s victims identify themselves as runaways and express a hatred for their parents. Upon hearing his victims express such sympathies, Howard is overcome by a powerful headache and driven into a murderous rage. He rapes his victims before strangling them with wire coat hangers, a modus operandi that suggests a bizarre kink or fetish. Following the murders, Howard remembers nothing of what has transpired; he returns to Baldwin’s laundry service unaware of where he has been, his missing hours a source of frustration for his employer. (‘All I know is, I found myself way out on a country road, with no memory of how I got there’, Howard tells his mother after the film’s first murder.) In his everyday life, the only connection Howard experiences to his crimes comes when he sees a news report of one of the murders, this triggering a flashback to the crime itself (represented for the audience by a smash cut to each murder). Howard’s murders are, we are led to believe, committed out of a sense of rage towards Howard’s own sister Judy, who abandoned her family six years prior to the start of the narrative, causing severe emotional distress to Howard’s beloved mother. In the film’s opening sequence, Howard picks up a hitchhiker before murdering her; during the murder, he beats her and calls her Judy (‘I’m gonna punish you, Judy!’). Later, when he picks up another school girl hitchhiker, the film ratchets up the tension – until the girl expresses her love for her home and mother, and Howard drops her off at her intended destination. Hitch Hike to Hell seems obviously to exist in the shadow of Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960): like so many post-Norman Bates serial killers, Howard has an unhealthy relationship with his other – which crosses the line from nurturing to smothering. In one scene, after a moment of psychological trauma, Howard climbs into bed with his mother, who coddles him like a baby. However, Howard is outwardly normal; Captain Shaw tells Pam’s parents that ‘He [the killer] isn’t wearing a sign around his neck’. Hitch Hike to Hell struggles to engage with the psychology of its killer, and where later serial killer pictures would often depict their protagonists in an manner laden with a (necessary) distancing irony, Hitch Hike to Hell manages to make Howard somewhat sympathetic. His murders are committed whilst Howard is in what can only be described as a dissociative fugue state that is triggered when Howard’s victims identify themselves as runaways and express a hatred for their parents. Upon hearing his victims express such sympathies, Howard is overcome by a powerful headache and driven into a murderous rage. He rapes his victims before strangling them with wire coat hangers, a modus operandi that suggests a bizarre kink or fetish. Following the murders, Howard remembers nothing of what has transpired; he returns to Baldwin’s laundry service unaware of where he has been, his missing hours a source of frustration for his employer. (‘All I know is, I found myself way out on a country road, with no memory of how I got there’, Howard tells his mother after the film’s first murder.) In his everyday life, the only connection Howard experiences to his crimes comes when he sees a news report of one of the murders, this triggering a flashback to the crime itself (represented for the audience by a smash cut to each murder). Howard’s murders are, we are led to believe, committed out of a sense of rage towards Howard’s own sister Judy, who abandoned her family six years prior to the start of the narrative, causing severe emotional distress to Howard’s beloved mother. In the film’s opening sequence, Howard picks up a hitchhiker before murdering her; during the murder, he beats her and calls her Judy (‘I’m gonna punish you, Judy!’). Later, when he picks up another school girl hitchhiker, the film ratchets up the tension – until the girl expresses her love for her home and mother, and Howard drops her off at her intended destination.

Video

Hitch Hike to Hell is presented in 1080p using the AVC codec. The film is uncut, with a running time of 88:10. Hitch Hike to Hell is presented in 1080p using the AVC codec. The film is uncut, with a running time of 88:10.

Shot on 16mm and blown up to 35mm, Hitch Hike to Hell is presented here in a new 2k restoration billed as being sourced ‘from original film elements’. This would seem to be a positive source (perhaps from a 35mm interpositive or print): contrast levels are fine, midtones having reasonable definition but the drop off into the toe is sharp and shadow detail is sometimes crushed whilst the push into the shoulder is also sometimes a little sharp. The structure is very coarse and again suggests the source as being a 35mm blow-up (rather than the negative). It’s natural and filmlike, however, with no overt evidence of digital tinkering. The 1.33:1 presentation takes up about 15Gb of space on the disc, and the 1.78:1 presentation fills approximately 18Gb of space. Some full-sized screengrabs comparing the 1.33:1 and 1.78:1 presentations can be found at the bottom of this review. (Please click to enlarge them.) As a brief glance will show, the 1.78:1 presentation is mostly centre-weighted though goes for a ‘common top’ framing in some shots – principally those which show Howard and his victims riding in the laundry van. These shots were bizarrely composed with the subject towards the top of the frame. (Given that the likelihood was that the film would be blown up to 35mm and matted to 1.75:1 or 1.85:1 for cinema exhibition, one can only presume that the viewfinder of the 16mm camera/s used to shoot the picture didn’t have 1.85:1 framelines and/or that the director of photography neglected to ‘protect’ for the screen ratio of the film’s theatrical release.) Damage is present in the form of some rough-looking optical sequences (eg, the printed main titles sequence), and the source is in fairly rough shape – with white flecks and specks present pretty much throughout the presentation. Nevertheless, all of this damage is organic and film-based, resulting in a very ‘authentic’-seeming presentation. Finally, the encode to disc presents no problems.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 track. This displays a reasonable amount of range, though sometimes dialogue seems a little too ‘bassy’. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are provided. These are accurate and easy to read.

Extras

The disc includes The disc includes

- ‘Of Monsters and Morality: The Strange Cinema of Irvin Berwick’ (29:01). Stephen Thrower looks back on the career of director Irv Berwick, which stretches back to the 1950s. Thrower talks about the diversity of Berwick’s career: for a number of years, Berwick worked as a dialogue coach with filmmakers such as Budd Boetticher and Jack Arnold. Thrower considers Berwick’s 1959 directorial debut, the horror movie The Monster of Piedras Blancas, which led Berwick to establish his own production company. Discussing Berwick’s subsequent pictures, Thrower argues that ‘quite a few of his [Berwick’s] films remain stubbornly unavailable’. Thrower reveals that Berwick’s son Wayne, the director of Microwave Massacre (1983), told Thrower – when Thrower interviewed Wayne for Thrower’s book Nightmare USA – that Irv Berwick directed 15 softcore sex pictures and a few hardcore features under a pseudonym; this would suggest Berwick helmed far more films than he is usually claimed to have made. - ‘Road to Nowhere: Hitchhiking Goes to Hell’ (21:27). In this video essay, Alexandra Heller-Nicholas uses Hitch Hike to Hell as a springboard for a reflection on the manner in which hitchhiking has been represented in exploitation cinema. She connects this to the rise of car culture during the mid-Twentieth Century, and talks about the centrality of hitchhiking to many American urban legends. Heller-Nicholas also examines the popularity of stories about hitchhiking in relation to the activities of serial killers and spree killers (such as Ted Bundy and the unsolved Santa Rosa hitchhiker murders) during the 1960s and 1970s – and the Highway of Tears in Canada, and backpacker murders in Australia during the 1990s. Heller-Nicholas’ discussion links urban myth, cinema and the evolving social reality of mid-Twentieth Century America.

- ‘Nancy Adams on the Road’ (24:52). Nancy Adams, who sang the film’s title song, discusses her varied career, from her first recording contract and her work for the Newport Cigarettes advertising campaign to her work on Disney’s Robin Hood (1973). Adams talks about how she came to record the title song for Hitch Hike to Hell, which was based on a tune she and her husband Floyd had written called ‘Lovin’ on My Mind’. Adams only recently got the chance to watch Hitch Hike to Hell, which she describes as a ‘rough movie’. - ‘Lovin’ on My Mind’ (2:24). Here is ‘Lovin’ on My Mind’, the original song by Nancy Adams, which she recorded with alternate lyrics as the title theme for Hitch Hike to Hell. - ‘Lovin’ on My Mind’ – Alternate Titles (3:02). The opening titles of the feature are played here with the original version of ‘Lovin’ on My Mind’ as their accompaniment. This is introduced by Nancy Adams. - Trailer: 1.33:1 version (2:21); 1.78:1 (2:21).

Overall

In its focus on a serial killer, Hitch Hike to Hell feels remarkably modern – much more like the serial killer pictures of the 1980s than those of the early/mid-1970s. Hitch Hike to Hell is uneven in its approach and unfocused in terms of its narrative: in the scenes at Baldwin’s laundry, the film introduces a character, Phyliss (Petra Michelle), who it is suggested might be a romantic match for Howard. However, this character is frustratingly underdeveloped. Nevertheless, the ‘flatness’ of the scenes at the laundry and the scenes involving Shaw and Davis arguably make the film’s almost fetishistic staging of the murders and their aftermath (the shots of the victims’ bodies staged to look remarkably like forensic photographs) more impactful. It’s certainly an interesting film though the unevenness of the production makes it difficult to recommend wholeheartedly; fans of serial killer fiction will find much to engage with here, however. In its focus on a serial killer, Hitch Hike to Hell feels remarkably modern – much more like the serial killer pictures of the 1980s than those of the early/mid-1970s. Hitch Hike to Hell is uneven in its approach and unfocused in terms of its narrative: in the scenes at Baldwin’s laundry, the film introduces a character, Phyliss (Petra Michelle), who it is suggested might be a romantic match for Howard. However, this character is frustratingly underdeveloped. Nevertheless, the ‘flatness’ of the scenes at the laundry and the scenes involving Shaw and Davis arguably make the film’s almost fetishistic staging of the murders and their aftermath (the shots of the victims’ bodies staged to look remarkably like forensic photographs) more impactful. It’s certainly an interesting film though the unevenness of the production makes it difficult to recommend wholeheartedly; fans of serial killer fiction will find much to engage with here, however.

Arrow’s Blu-ray release of Hitch Hike to Hell contains a pleasing enough presentation of this shot-on-16mm feature alongside some excellent contextual material. Stephen Thrower’s discussion of Irv Berwick’s career is as engaging and well-researched as one would expect, and Alexandra Heller-Nicholas’ video essay focusing on hitchhiking is equally strong. Please click to enlarge. 1.78:1

1.33:1

1.78:1

1.33:1

1.78:1

1.33:1

1.78:1

1.33:1

1.78:1

1.33:1

1.78:1

1.33:1

1.78:1

1.33:1

1.78:1

1.33:1

|

|||||

|