|

|

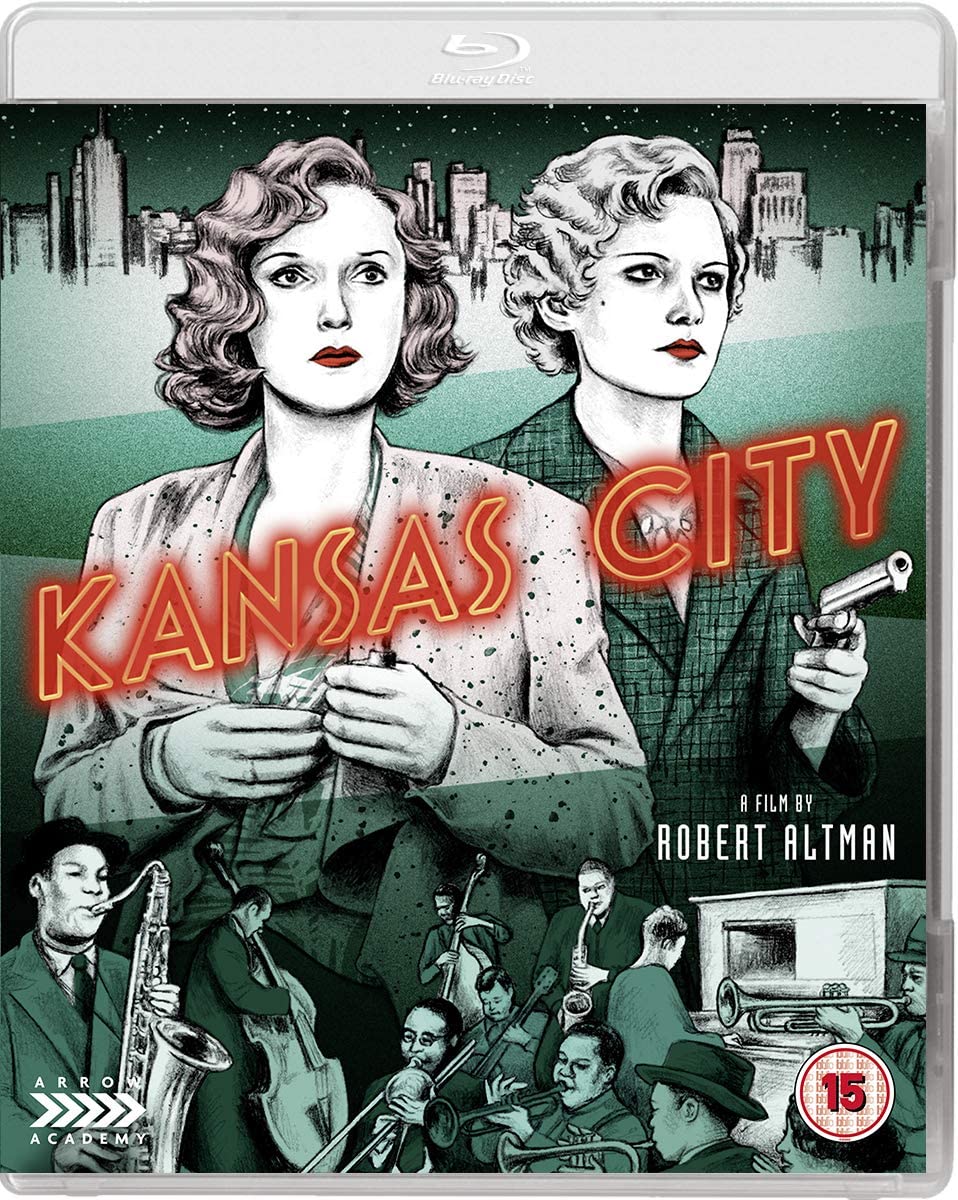

Kansas City (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (20th April 2020). |

|

The Film

Kansas City (Robert Altman, 1996) Kansas City (Robert Altman, 1996)

Synopsis: Kansas City, 1934. On the eve of the mayoral election, masquerading as a visiting manicurist, Blondie (Jennifer Jason Leigh) abducts wealthy, laudanum-addicted Carolyn Stilton (Miranda Richardson) from her luxurious home. Blondie takes Stilton with the hope of exerting pressure on her husband, Henry Stilton (Michael Murphy), a regional bigwig in the Democratic Party, to help return Blondie’s husband, Johnny (Dermot Mulroney). Johnny has been abducted by black kingpin Seldom Seen (Harry Belafonte), the owner of Kansas City’s Hey Hey Club, after Johnny robbed one of Seldom’s out-of-town associates, Sheepshan Red (A C Smith). Johnny dressed in ‘blackface’ to rob Sheepshan, enlisting the help of one of Seldom’s drivers, ‘Blue’ Green, played by Martin Martin; the naivete of Johnny’s plan is something that is both a source of humour and anger for the shrewd Seldom. Critique: After forging a reputation during the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s as a key auteur within the Hollywood Renaissance – thanks to the impact of films such as M*A*S*H (1970), McCabe and Mrs Miller (1971), The Long Goodbye (1973, Arrow’s Blu-ray release of which was reviewed by us here), and Nashville (1975) – in the late 1970s Robert Altman turned his attention to making a number of more experimental films, including 3 Women (1977, Arrow’s Blu-ray release of which was also reviewed by us) and A Wedding (1978). These films’ lack of commercial success alienated Hollywood, at a time when studios were attempting to capitalise on the blockbuster success of films like Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975) and Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977). Furthermore, as Charles Warren has suggested, films such as 3 Women and Quintet (1979) ‘gave Altman the reputation of an art film director’ which led to ‘large budget productions [being] not viable [for Altman] for a time’ (Warren, 2013: 27). After a run of pictures that were critically acclaimed but not financially successful, Altman’s subsequent attempt at competing in the post-Jaws ‘blockbuster’ marketplace, 1980’s Popeye, is often cited alongside Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate (1980) as one of the films that signalled the end of the Hollywood Renaissance – a picture that symbolised the excesses of the American auteur filmmakers of the Hollywood Renaissance era.  After Popeye, Altman struggled to compete in Hollywood and complemented his work on films with much more restricted budgets with work in theatre and television. In the 1990s, the successes of The Player (1992) allowed Altman to make a number of pictures that were closer in scale, and their narrative ambitions, to the films he had directed in the 1970s. These films included Short Cuts (1993), Pret-a-Porter (1994) and Kansas City (1996). After Popeye, Altman struggled to compete in Hollywood and complemented his work on films with much more restricted budgets with work in theatre and television. In the 1990s, the successes of The Player (1992) allowed Altman to make a number of pictures that were closer in scale, and their narrative ambitions, to the films he had directed in the 1970s. These films included Short Cuts (1993), Pret-a-Porter (1994) and Kansas City (1996).

Altman had been born and raised in Kansas City and would have been 9 in 1934, the year in which the film’s story is set. However, Kansas City is far from a nostalgic look at Altman’s childhood stomping-ground. Adrian Danks has noted that Kansas City ‘never really feels like a reminiscence’ and therefore stands apart from ‘such explicitly and impressionistically autobiographical works as Federico Fellini’s Roma (1972), Barry Levinson’s Diner (1982), John Boorman’s Hope and Glory (1987) and Terence Davies’ The Long Day Closes (1992)’ (Danks, 2015: 327). The picture takes some inspiration from the milieu surrounding the 1933 kidnapping of Mary McElroy, an opium addict and the daughter of the city manager of Kansas City, Henry F McElroy, who had close ties to Thomas J Pendergast. The de facto ‘boss’ of Kansas City and Jackson County from the mid-1920s to 1939, Pendergast was the Chairman of the Jackson County Democratic Party and mixed with politicians and criminals alike; he wasn’t above using electoral fraud to help his associates reach political positions in both Jackson County and Kansas City. Harry S Truman’s brief and distant association with Pendergast in the early years of his political career led to Truman being labelled ‘the Senator from Pendergast’ by his opponents. Prior to her kidnapping, McElroy had been known to circulate with figures from the world of organised crime, mixing with the likes of mobster Johnny Lazia, an employee of her father’s. After 34 hours in captivity, McElroy was released following the payment of a ransom of $30,000 for her safe return. Three of the four men responsible for her kidnapping – brothers George and Walter McGee, and their associate Clarence Click – were apprehended and sentenced within a month of McElroy’s release. The fourth member of the gang, Clarence Stevens, went on the lam and disappeared. (Rumour has it that Stevens fled to Oregon.) Walter McGee, considered the mastermind behind the kidnapping, was sentenced to death; however, after McElroy and her father pleaded for a different sentence, McGee was eventually given life in prison instead.  A little more than a year after McElroy had been released by the gang, she and criminal James Henry ‘Blackie’ Audett drove to Kansas City Union Station, as McElroy wanted to witness the event that came to be known as the Kansas City Union Station Massacre. This was an event about which, owing to the pair’s underworld connections, they had foreknowledge. The ‘massacre’ took place on the orders of Johnny Lazia, targeting the bank robber Frank ‘Jelly’ Nash, who had recently been captured by the police. An associate of the Barker brothers, ‘Machine Gun’ Kelly and other dangerous criminals, Nash was being transported by train to Leavenworth, and at Union Station he was being handed over by two Kansas City detectives to the FBI. It’s not entirely clear whether Lazia aimed to spring Nash from custody or to kill him (to ensure his silence), though the latter seems more likely. Nash was killed in the gunfight, along with two Kansas City policemen, Oklahoma police chief Otto Reed, and FBI agent special agent Ray Caffey. The FBI believed that Charles Arthur ‘Pretty Boy’ Floyd and Arthur Richetti were responsible for the massacre, though Audett and McElroy (too conveniently) claimed that neither men were present that day. Needless to say, Audett and McElroy’s testimonies weren’t believed by the FBI. Under the orders of J Edgar Hoover, the FBI pursued Floyd and Richetti, the former elevated to Public Enemy Number One after the death of John Dillinger in July 1934. In October of that year, FBI agent Melvin Purvis shot and killed Floyd. Richetti, who had already been arrested, was executed in the gas chamber in 1938. The body of Vernon Miller, who without doubt was involved in the massacre, was found in a car a few months later, having been strangled with a clothesline and beaten to death with a clawhammer. Apparently unable to cope with the emotional fallout from her kidnapping, and devastated by her father’s death in 1939, Mary McElroy committed suicide in 1940 by shooting herself in the head. A little more than a year after McElroy had been released by the gang, she and criminal James Henry ‘Blackie’ Audett drove to Kansas City Union Station, as McElroy wanted to witness the event that came to be known as the Kansas City Union Station Massacre. This was an event about which, owing to the pair’s underworld connections, they had foreknowledge. The ‘massacre’ took place on the orders of Johnny Lazia, targeting the bank robber Frank ‘Jelly’ Nash, who had recently been captured by the police. An associate of the Barker brothers, ‘Machine Gun’ Kelly and other dangerous criminals, Nash was being transported by train to Leavenworth, and at Union Station he was being handed over by two Kansas City detectives to the FBI. It’s not entirely clear whether Lazia aimed to spring Nash from custody or to kill him (to ensure his silence), though the latter seems more likely. Nash was killed in the gunfight, along with two Kansas City policemen, Oklahoma police chief Otto Reed, and FBI agent special agent Ray Caffey. The FBI believed that Charles Arthur ‘Pretty Boy’ Floyd and Arthur Richetti were responsible for the massacre, though Audett and McElroy (too conveniently) claimed that neither men were present that day. Needless to say, Audett and McElroy’s testimonies weren’t believed by the FBI. Under the orders of J Edgar Hoover, the FBI pursued Floyd and Richetti, the former elevated to Public Enemy Number One after the death of John Dillinger in July 1934. In October of that year, FBI agent Melvin Purvis shot and killed Floyd. Richetti, who had already been arrested, was executed in the gas chamber in 1938. The body of Vernon Miller, who without doubt was involved in the massacre, was found in a car a few months later, having been strangled with a clothesline and beaten to death with a clawhammer. Apparently unable to cope with the emotional fallout from her kidnapping, and devastated by her father’s death in 1939, Mary McElroy committed suicide in 1940 by shooting herself in the head.

Kansas City juxtaposes several very different social groups. At the top of the heap is the political class, represented by Henry Stilton and his wife. The backdrop of the film is the 1934 election, in which the state of Missouri’s incumbent Republican senator Roscoe Patterson was ousted in favour of the Democrat Harry S Truman, who would of course go on to become the 33rd President of the United States. Kansas City’s 1934 mayoral election would consolidate the power of Bryce Smith, an ally of Pendergast’s, who would remain the mayor of Kansas City until 1939. Described as the ‘bloody election’, the 1934 elections in Kansas City were surrounded by intimidation and violence – of which the Union Station Massacre was only the tip of the iceberg – and marked by fraud. Pendergast and his associates would bus people in to the region to vote fraudulently, sometimes under the names of individuals who were already deceased. Kansas City juxtaposes several very different social groups. At the top of the heap is the political class, represented by Henry Stilton and his wife. The backdrop of the film is the 1934 election, in which the state of Missouri’s incumbent Republican senator Roscoe Patterson was ousted in favour of the Democrat Harry S Truman, who would of course go on to become the 33rd President of the United States. Kansas City’s 1934 mayoral election would consolidate the power of Bryce Smith, an ally of Pendergast’s, who would remain the mayor of Kansas City until 1939. Described as the ‘bloody election’, the 1934 elections in Kansas City were surrounded by intimidation and violence – of which the Union Station Massacre was only the tip of the iceberg – and marked by fraud. Pendergast and his associates would bus people in to the region to vote fraudulently, sometimes under the names of individuals who were already deceased.

The political fraud and corruption of the Pendergast era is dealt with directly in Kansas City. As the narrative progresses Altman shows, in the background of the central story at first, the build-up to election day itself, Blondie’s brother-in-law Johnny Flynn (Steve Buscemi) presiding over dozens of itinerants brought into the city limits in order to bolster the vote for the Democratic candidate. Flynn uses violence to intimidate these men. The Democrats rally around Union Station, the site of the aforementioned massacre engineered by Johnny Lazia and carried out by Vernon Miller and accomplices unknown – or perhaps Pretty Boy Floyd and Arthur Richetti, if McElroy and Audett’s testimonies are to be disbelieved. The interests of the criminal class, the film’s second group, is shown to be intertwined with the political elite. The third group is the community of African Americans that revolves around Seldom Seen’s Hey Hey Club, the uplifting jazz in its front of house offset by the shady gambling that occurs in the shadows, and the politicking and violence which takes place in the back rooms. James Philips has stated that Kansas City ‘juxtaposes […] the macropolitics of the 1938 [sic] presidential election with the micropolitics of African American economic survival as it is functioning within a diasporic jazz culture’ (Philips, 2008: 52). Discussing the ‘thinness’ of the film’s plotting, Philips reminds his readers of Altman’s assertion that the film’s narrative ‘is just a little song, and it’s the way it’s played that’s important’ (Altman, quoted in ibid.). The political fraud and corruption of the Pendergast era is dealt with directly in Kansas City. As the narrative progresses Altman shows, in the background of the central story at first, the build-up to election day itself, Blondie’s brother-in-law Johnny Flynn (Steve Buscemi) presiding over dozens of itinerants brought into the city limits in order to bolster the vote for the Democratic candidate. Flynn uses violence to intimidate these men. The Democrats rally around Union Station, the site of the aforementioned massacre engineered by Johnny Lazia and carried out by Vernon Miller and accomplices unknown – or perhaps Pretty Boy Floyd and Arthur Richetti, if McElroy and Audett’s testimonies are to be disbelieved. The interests of the criminal class, the film’s second group, is shown to be intertwined with the political elite. The third group is the community of African Americans that revolves around Seldom Seen’s Hey Hey Club, the uplifting jazz in its front of house offset by the shady gambling that occurs in the shadows, and the politicking and violence which takes place in the back rooms. James Philips has stated that Kansas City ‘juxtaposes […] the macropolitics of the 1938 [sic] presidential election with the micropolitics of African American economic survival as it is functioning within a diasporic jazz culture’ (Philips, 2008: 52). Discussing the ‘thinness’ of the film’s plotting, Philips reminds his readers of Altman’s assertion that the film’s narrative ‘is just a little song, and it’s the way it’s played that’s important’ (Altman, quoted in ibid.).

At several points throughout the film, Seldom Seen underscores the naivete of Johnny’s plan, which involved Johnny donning blackface in order to rob Sheepshan. Immediately following Johnny’s capture, Seldom Seen mocks Johnny, accusing him of ‘com[ing] swinging in here like Tarzan, right in the middle of a sea of niggers, like you’re in a picture show’. A number of times afterwards, Seldom compares Johnny and Blue, the black cab driver who betrayed Seldom in order to assist Johnny in the heist, to Amos and Andy, the minstrelsy radio characters essayed by Freman Gosden and Charles Correll. Seldom’s criticisms of Johnny’s plan culminates in a broader dismissal of ‘Movies and radio. White people just sitting around all day, thinking up that shit; and then they believe it’. This statement is central to the film. With her Jean Harlow obsession, which results in a botched attempt to dye her hair blonde (hence the short ‘do’), Blondie’s ludicrous plot to kidnap Mrs Stilton, in order to exert pressure on Henry Stilton to assist in ‘rescuing’ Johnny from Seldom, also seems to be lifted from the movies. A number of times, Altman cuts to a photograph of Blondie and Johnny striking a Bonnie and Clyde-style pose. Ironically, however, the true story of the McElroy kidnapping and the circumstances surrounding it – filled with its nebulous ‘what ifs’ – is in itself fantastical enough to be the plot of a film. At several points throughout the film, Seldom Seen underscores the naivete of Johnny’s plan, which involved Johnny donning blackface in order to rob Sheepshan. Immediately following Johnny’s capture, Seldom Seen mocks Johnny, accusing him of ‘com[ing] swinging in here like Tarzan, right in the middle of a sea of niggers, like you’re in a picture show’. A number of times afterwards, Seldom compares Johnny and Blue, the black cab driver who betrayed Seldom in order to assist Johnny in the heist, to Amos and Andy, the minstrelsy radio characters essayed by Freman Gosden and Charles Correll. Seldom’s criticisms of Johnny’s plan culminates in a broader dismissal of ‘Movies and radio. White people just sitting around all day, thinking up that shit; and then they believe it’. This statement is central to the film. With her Jean Harlow obsession, which results in a botched attempt to dye her hair blonde (hence the short ‘do’), Blondie’s ludicrous plot to kidnap Mrs Stilton, in order to exert pressure on Henry Stilton to assist in ‘rescuing’ Johnny from Seldom, also seems to be lifted from the movies. A number of times, Altman cuts to a photograph of Blondie and Johnny striking a Bonnie and Clyde-style pose. Ironically, however, the true story of the McElroy kidnapping and the circumstances surrounding it – filled with its nebulous ‘what ifs’ – is in itself fantastical enough to be the plot of a film.

Video

Filling approximately 35Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, Kansas City runs for 115:41 mins. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and is in the 1.78:1 aspect ratio. Filling approximately 35Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, Kansas City runs for 115:41 mins. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and is in the 1.78:1 aspect ratio.

The film’s 35mm colour photography is captured very well on this Blu-ray release. An excellent level of fine detail is present throughout the film. The film’s photography, by Oliver Stapleton, makes similar use of lowkey lighting to Stapleton’s work on Stephen Frear’s The Grifters (1990). Colours are muted, the palette dominated by earthy browns and greens. The scenes featuring lowkey lighting are captured very well, with pleasingly defined midtones tapering off into deep shadows. (Shadow detail is sometimes slightly ‘crushed’.) These scenes have a slight underexposed look, which seems to be deliberate on the part of Stapleton. The daytime scenes are equally pleasing in terms of contrast, with the sometimes harsh lighting of the exterior scenes being contrasted with the lowkey lighting of the interiors. There may be some very slight digital sharpening evident in one or two places, but the image shows little to no evidence of harmful digital tinkering. The encode to disc retains the structure of 35mm film. Some full-sized screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

The disc presents the viewer with the option of watching the film with either a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track or a LPCM 2.0 track, with optional English subtitles for the Hard of hearing. Both audio tracks are pleasingly deep and rich, with excellent range that is articulated in the scenes in the Hey Hey Club which feature some excellent, though slightly anachronistic, jazz. The 5.1 track has an added sense of depth with some atmospheric directional sound, particularly in the Hey Hey Club scenes but also in some of the more dialogue-heavy scenes.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary by Robert Altman. Altman offers an excellent commentary, recorded for the film’s DVD release. Altman talks about his memories of Kansas City and how some of the events and experiences there worked their way into the film. He discusses his working relationships with the film’s various actors, and he also offers comments on the importance of jazz music. - ‘Geoff Andrew on Kansas City’ (25:20). Newly-recorded, in this interview critic Geoff Andrew reflects on the placing of Kansas City within Altman’s career. He begins by suggesting that the picture isn’t ‘one of the best known’ within Altman’s body of work, and exploring the relevance of the film’s setting for Altman. Andrew talks about some of Altman’s methods as a director, reflecting on Altman’s use of improvisation, overlapping sound and telephoto lenses to create a sense of ‘eavesdropping’. Andrew makes a strong case for Altman’s impact in terms of ‘transforming’ American cinema during the mid-20th Century. - Luc Lagier: ‘Introduction’ (3:49); ‘Gare, Trains and Deraillements’ (15:56). Recorded for the 2007 French DVD release of Kansas City, these audio interviews with French critic Luc Lagier consider the position of the film within Altman’s career, and in the second piece Lagier reflects on the film’s relationship with the social context of the setting, discussing Roosevelt’s presidency, the New Deal and Kansas City’s strategic position within the infrastructure of America.. In French with optional English subtitles. - Electronic Press Kit: ‘Robert Altman Goes to the Heart of America’ (8:45); ‘Kansas City: The Music’ (9:20); Robert Altman (2:23); Jennifer Jason Leigh (2:50); Miranda Richardson (2:34); Harry Belafonte (3:33); Joshua Redman (2:06); Behind the Scenes (2:20). These interviews were recorded to promote the film, but far from being simple ‘puff pieces’ the first piece in particular, ‘Robert Altman Goes to the Heart of America’, allows Altman a platform to explain some of his worldview and approach to filmmaking. ‘Kansas City: The Music’ explores the centrality of jazz music to the picture and Altman’s approach to its narrative. - International Trailer (2:25); US Trailer (2:27); French Trailer (1:38); German Trailer (1:38); US TV Spots (1:06) - Image Gallery (4:20)

Overall

Themes of both political corruption and racketeering bubble away in a number of Altman’s films; Altman perhaps shows the roots of this in the frontier politics that are depicted in McCabe and Mrs Miller. Kansas City foregrounds these themes in its layered narrative, contrasting the inhabitants of Seldom Seen’s club with both the Stiltons and Blondie. Telephones and telephone calls link the characters, though as Adrian Danks has noted, there is ‘an almost Mabusian sense of power’ that is represented through the scenes in which characters telephone one another (Danks, op cit.: 333). The ‘“shadowy” political figures’ communicate solely through telephones and rarely, if ever, leave ‘their dining rooms, cozy studies or headquarters’; on the other hand, Blondie is forced to use other people’s telephones in her attempts to communicate with Henry Stilton (ibid.). Against the main narrative Altman also establishes the story of Pearl (Ajia Mignon Johnson), a character loosely based on Rebecca Ruffin, who lodged with Charlie Parker’s family and eventually became Parker’s wife. Pearl is a young, pregnant black girl who has been sent to Kansas City to be placed in the care of the Junior League where she is to have her baby. At Union Station, Pearl and the Junior League miss one another, and Pearl meets a then-14 year old Charlie Parker (Albert J Burnes). Pearl and Charlie visit the Hey Hey Club, and their sense of innocent wonder at the music there seems to encapsulate Altman’s approach to the jazz scenes that punctuate the film and give life to its otherwise stifling story. Themes of both political corruption and racketeering bubble away in a number of Altman’s films; Altman perhaps shows the roots of this in the frontier politics that are depicted in McCabe and Mrs Miller. Kansas City foregrounds these themes in its layered narrative, contrasting the inhabitants of Seldom Seen’s club with both the Stiltons and Blondie. Telephones and telephone calls link the characters, though as Adrian Danks has noted, there is ‘an almost Mabusian sense of power’ that is represented through the scenes in which characters telephone one another (Danks, op cit.: 333). The ‘“shadowy” political figures’ communicate solely through telephones and rarely, if ever, leave ‘their dining rooms, cozy studies or headquarters’; on the other hand, Blondie is forced to use other people’s telephones in her attempts to communicate with Henry Stilton (ibid.). Against the main narrative Altman also establishes the story of Pearl (Ajia Mignon Johnson), a character loosely based on Rebecca Ruffin, who lodged with Charlie Parker’s family and eventually became Parker’s wife. Pearl is a young, pregnant black girl who has been sent to Kansas City to be placed in the care of the Junior League where she is to have her baby. At Union Station, Pearl and the Junior League miss one another, and Pearl meets a then-14 year old Charlie Parker (Albert J Burnes). Pearl and Charlie visit the Hey Hey Club, and their sense of innocent wonder at the music there seems to encapsulate Altman’s approach to the jazz scenes that punctuate the film and give life to its otherwise stifling story.

Kansas City is a film about imitation and reality, power and inequality. There are some interesting parallels with Francis Ford Coppola’s The Cotton Club (1984), which has recently been re-edited and rereleased in the US. Like that film, Kansas City was received in a less-than-lukewarm fashion, some critics wrinkling at Jennifer Jason Leigh’s deliberately grating performance. Some also criticised the somewhat anachronistic jazz played by the musicians in the film. Both criticism seemed quite churlish at the time and seem even more petty today, especially given the film’s many strengths – and among the superb performances, those of Harry Belafonte and Miranda Richardson stand out. Time has been kind to the film, and it seems to have an increasing relevance when viewed in the context of the fallout from the Black Lives Matter protests and the controversies surrounding the 2016 presidential elections in the US. Whilst not necessarily ‘top tier’ Altman, Kansas City is certainly an interesting film, and makes for a fascinating companion piece with Altman’s celebrated 2002 picture Gosford Park – in terms of its focus on social inequality. Arrow’s new Blu-ray release of Kansas City contains a very pleasing, filmlike presentation of the main feature, alongside some very strong contextual material. References: Danks, Adrian, 2015: ‘“The Man I Love,” or Time Regained: Altman, History and Kansas City’. In: Danks, Adrian (ed), 2015: A Companion to Robert Altman. London: Wiley-Blackwell Horeck, Tanya, 2000: ‘Robert ALTMAN’. In: Allon, Yoram et al (eds), 2000: Contemporary North American Film Directors. London: Wallflower Press: 8-11 Kolker, Robert Phillip, 2011: A Cinema of Loneliness. Oxford University Press (Revised Edition) Philips, James, 2008: Cinematic Thinking: Philosophical Approaches to the New Cinema Thompson, David, 2006: Altman on Altman. London: Faber & Faber Warren, Charles, 2013: ‘ALTMAN, Robert’. In: Justin, Wintle (ed), 2013: New Makers of American Culture, Volume 1. London: Routledge: 26-8 Wood, Robin, 2003: Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan… and Beyond. Columbia University Press (Revised Edition) Please click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|