|

|

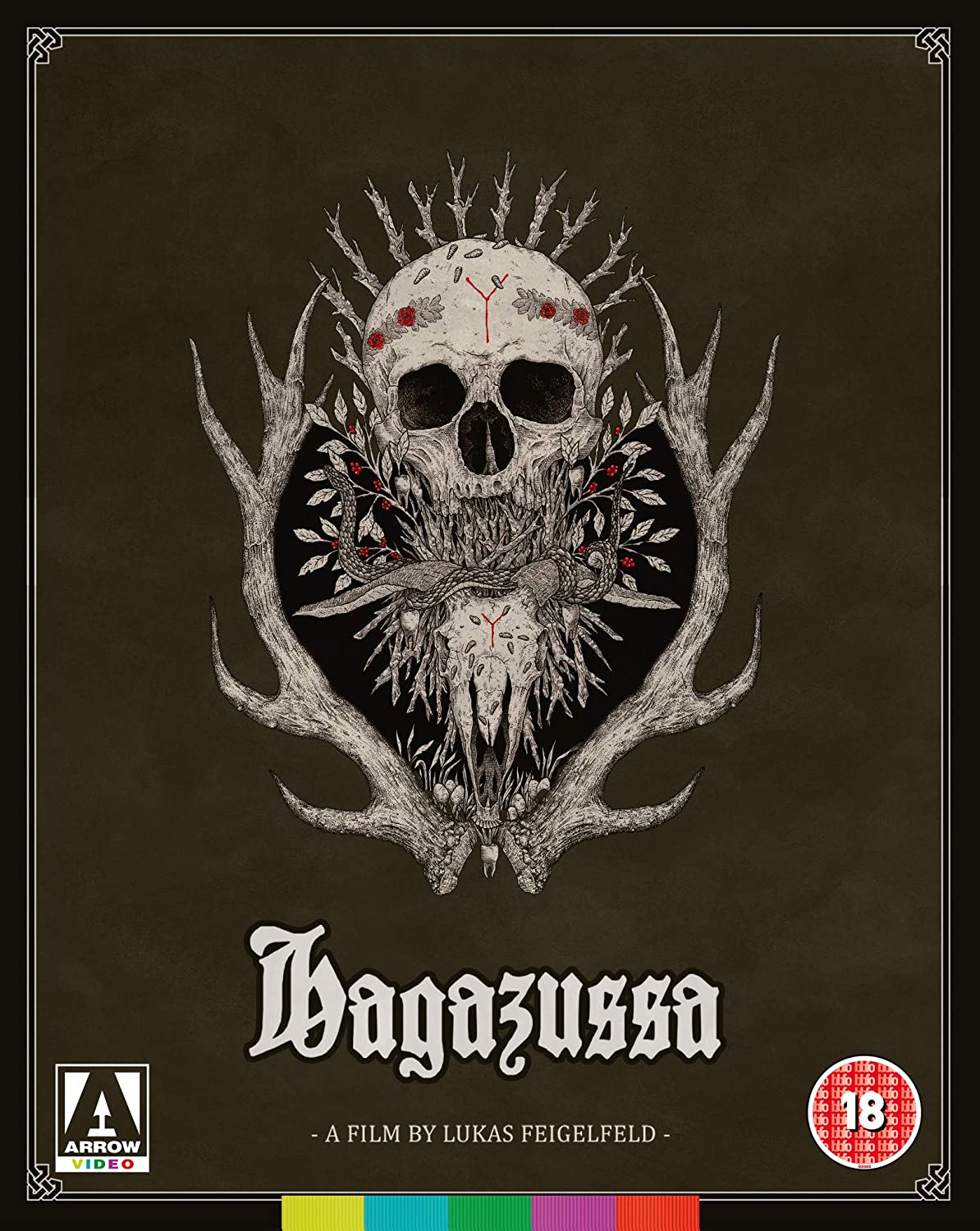

Hagazussa: A Heathen's Curse AKA Hagazussa (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Video Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (2nd May 2020). |

|

The Film

Hagazussa: A Heathen’s Curse (Lukas Feigelfeld, 2017) Synopsis: Part One – Shadows. In a location near the Alps, at some point in the 15th Century, Martha (Claudia Martini) and her daughter Albrun (Celina Peter) live an isolated existence. When Martha contracts the plague, her health deteriorates rapidly and her behaviour becomes increasingly strange. Martha dies, leaving Albrun to fend for herself. Part Two – Horn. We next meet Albrun as an adult (played by Aleksandra Cwen). Working as a goat herd, Albrun lives alone with a baby, who she has named after her mother. She is tormented by the local youngsters (‘Nobody wants your rotten milk here, you ugly witch’). Called to see the local priest in a church that also functions as an ossuary, Albrun remains silent but returns with her mother’s skull, around whose crown she paints a wreath of laurel, placing the skull in a corner of her cabin. The priest has given Albrun the skull apparently in hopes of ‘cleansing’ the community. Albrun is approached by Swinda (Tanka Petrovskij). Swinda presents herself as an ally but engineers a situation in which Albrun is sexually assaulted by one of the young men from the village. When Albrun returns to her cabin, she finds her prized goat butchered, its mutilated carcass strung up in Albrun’s goat shed. In retaliation, Albrun contaminates the village’s water supply by placing a dead rat in the head of the stream and urinating into the water. People in the village, including Swinda and the young man, die – either from the plague or from Albrun’s contamination of its water. Part Three – Fire. Albrun’s world becomes increasingly threatening as her mental state deteriorates and her hold on reality grows brittle. After consuming a wild mushroom, she experiences terrifying visions, including the return of her mother. Critique: ‘Hagazussa’ is an Old High German word which is the origin of the English word ‘hag’ and also the likely root of the modern German word ‘Hexe’ (the Anglo-Saxon equivalent is ‘witch’). Translating as ‘hedge-woman/sitter’, the term ‘Hagazussa’ dates back to the Neolithic era, when whilst the younger members of a village would be engaged in agricultural labour on land that had been cleared and planted, the older women of the group would sit by the hedges along the treelines that formed the boundaries of the known and tamed landscape. There, these women would collect herbs which would be used in medicinal potions. Beyond the boundary, there was of course danger from wild animals, and ancient peoples also believed that spirits dwelled in the forests; both were kept away from the heart of the community by the hedges that grew along these boundaries. Thus, the ‘hedge-sitters’ – the older women of village – occupied a liminal position, at the physical edge of the tamed landscape, and on the boundary between the living and the dead. As the concept of the witch (‘Hexe’) evolved, the notion of these women flying through the night sky on bundles of sticks collected from such hedges (‘Hag’) became prevalent. Although Lukas Feigelfeld’s Hagazussa draws richly on folklore surrounding witches and contains many intimations of the supernatural, the film never ‘confirms’ these suggestions. From her childhood, Albrun is a pariah within the community, a victim of prejudice. Her mother, Martha, with whom the young Albrun lives on the border between the forest and cultivated land (effectively as a ‘hedge sitter’) is labelled as a ‘witch’ by the locals; this label carries over into Albrun’s adulthood. Likewise, ambiguity surrounds Albrun’s baby, and it is unclear whether or not this child is alive or even real. The film is heavily focalised through Albrun, and therefore the film’s visual narration is potentially unreliable. (The amount of time for which she leaves the child alone each day suggests that the baby may not exist – or may be a stillborn child, already dead when we meet it – but that Albrun is imagining it into existence/life.) In its opening sequences, featuring the young Albrun and her mother Martha, Hagazussa establishes the Alpine locale as harsh and forbidding. In an overhead shot, the ground blanketed in snow, we see Martha dragging a sled on which Albrun is seated. They encounter an old man, Sepp, who reminds them to hurry home as it is Twelfth Night. ‘Watch out that Pertcha doesn’t get you’, he warns, referring to Frau Pertcha, the Pagan goddess who was said to wander through the landscape during the winter period and punish naughty children by disembowelling them. In their cabin, the wind howls outside whilst Martha and Albrun struggle to keep warm. Insistent banging on the cabin door disrupts their evening. ‘You should be burned down, you witches’, an angry male voice asserts, ‘We’ll get you’. Martha becomes ill, pus-filled boils in her armpits suggesting the plague. As Martha’s health deteriorates, her behaviour becomes increasingly erratic, culminating with her calling Albrun into her bed, where Martha sexually assaults her daughter. The next day, Albrun discovers her mother dead. In the film’s second part, the landscape is green and apparently fertile, but the now-adult Albrun is still regarded as coldly as before. She is subjected to the taunting of the local young people, and is treated unsympathetically by the priest – who tells Albrun that his aim is ‘to strengthen the faith of a religious community [by ensuring] all sacrilege is cleansed’, before giving Albrun the skull of her mother. When Swinda apparently befriends Albrun, it seems that Albrun develops sexual feelings for the other woman – which manifests in Albrun’s sexualised caressing of the udders of one of her goats, followed by Albrun masturbating in her bed. Throughout this, however, the forest – the territory beyond the known, tamed landscape – represents mystery and possible threat. Her cabin on the cusp of the cultivated landscape, Albrun finds herself walking through the forest frequently, at times staring into the shadows in the distance; we share her point-of-view, wondering if something may be concealed amongst the trees. The film’s climax is precipitated by Albrun’s consumption of a wild mushroom which causes deeply unsettling hallucinations that draw already barely-suppressed primal fears to the surface.

Video

NB. This review is based on a viewing of a streaming link that was provided to us. Therefore we cannot comment in detail on the Blu-ray presentation, audio or extras. Photographed digitally and presented in the 2.39:1 screen ratio, Hagazussa runs for 102:08 mins. Much of the film, particularly the scenes in Martha and Albrun’s cabin, takes place in low-light. These scenes make very evocative use of what seems to be ambient light (or an imitation of it). The palette is dominated by earthy colours.

Audio

The film’s sound design is highly atmospheric, with much use of ambient sound effects (for example, wind) to create a sense of unease. Hagazussa also benefits from an incredible, haunting score by Greek due MMMD which amplifies the sense of tension. According to press materials, Arrow’s Blu-ray release contains a choice of a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track and a LPCM 2.0 stereo track, with optional English subtitles.

Extras

Arrow’s Blu-ray release contains the following contextual material: - An audio commentary by critic Kat Ellinger - A selected scene audio commentary by director Lukas Feigelfeld - Two shorts films by Feigelfeld: ‘Beton’ and ‘Interferenz’. - A deleted scene with optional commentary by Lukas Feigelfeld. - A music video for MMMD’s score. - Trailer and Teaser. A Limited Edition (2000 units) also contains the film's soundtrack on CD.

Overall

Comparisons between Hagazussa, the debut of its director Lukas Feigelfeld, and Robert Eggers’ fairly recent The Witch (2016) are all too obvious. Both Hagazussa and The Witch depict their 15th/16th/17th Century settings in textures that recall John Coquillon’s photography for Michael Reeves’ Matthew Hopkins: Witchfinder General (1968), in a palette dominated by earthy, drab greens and browns. Filled with ambiguities, Hagazussa is also rich in references to folklore, culminating in a haunting/traumatising sequence that confronts some of the profound cultural connotations of cannibalism. What’s remarkable is Feigelfeld’s handling of the material: the director has the confidence to leave many events and narrative situations to the viewers’ imagination. This, along with the thick texture of the film that is carried through the evocative photography and haunting score, ensures that Hagazussa is a memorable experience – though its bleak, hopeless and despairing (and some might say, slow) approach to the material may not be for everyone.

|

|||||

|