|

|

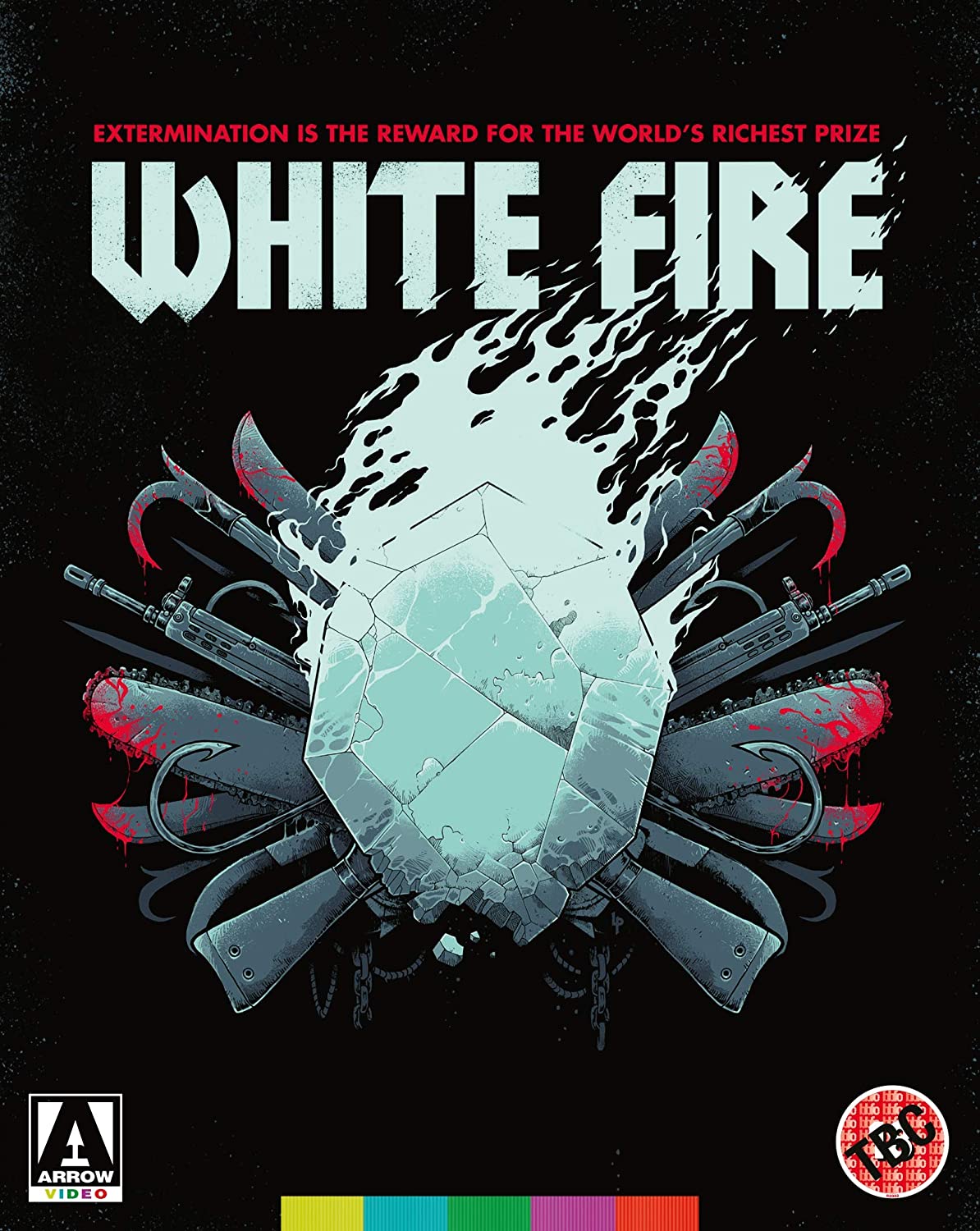

White Fire AKA Vivre pour survivre (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (24th June 2020). |

|

The Film

Vivre Pour Survivre AKA White Fire (Jean-Pierre Pallardy, 1984) Vivre Pour Survivre AKA White Fire (Jean-Pierre Pallardy, 1984)

Synopsis: Having witnessed the violent deaths of their parents during childhood at the hands of mercenaries in an undisclosed country, and being rescued by American smuggler Sam (Jess Hahn), Bo (Robert Ginty) and his younger sister Ingrid (Belinda Mayne) have an… unusually close relationship. Ingrid works for a diamond mine. Her boss is the sadistic Yilmaz, the mine’s security officer. Ingrid has been stealing diamonds from the mine with her brother Bo; the pair pass these diamonds on to Sam, who is working for smuggler Apaydin. Bo and Ingrid are abducted at gunpoint by Barbossa (Benito Stefanelli) and Sophia (Mirella Banti), gangsters who want a cut of the smuggling action. Bo and Ingrid escape but suspect Apaydin of double-crossing them. Meanwhile, in the mine a worker discovers a huge diamond – a mythical stone forged millennia ago. In legend, this diamond has been given the name ‘White Fire’. Radioactive, the White Fire diamond will burn anyone who touches it. After the mine worker tells Yilmaz and Ingrid about finding the White Fire, Yilmaz murders the employee in cold blood, in order to prevent news of its discovery from spreading. Ingrid tells Bo about the White Fire diamond, and the pair concoct a plan to steal it; this will allow them to leave Turkey. However, before they can do this, Ingrid is murdered by Sophia’s goons. Drowning his sorrows in a bar, Bo meets prostitute Olga (Diana Goodman), who bears a striking resemblance to Ingrid. Bo and Sam conspire to send Olga to rogue plastic surgeon Champi Doré, who transforms Olga into the exact double of Ingrid. Bo teaches Olga how to behave like Ingrid, and the pair grow close. Bo, Olga and Sam conspire to enable Olga to take Ingrid’s place at the diamond mine, facilitating the theft of the White Fire. However, they are unaware that Olga is being hunted down by cruel Noah (Fred ‘The Hammer’ Williamson) and his gang, on behalf of her pimp Olaf. Meanwhile, Bo and Sam are still being pursued by Sophie and Barbossa.  Critique: An international co-production between companies based in at least four (count ‘em) NATO countries, White Fire (aka Vivre pour survivre) feels for all intents and purposes like a huge tax write-off, or one of those pop-up, always-empty businesses in your neighbourhood that everyone insists is a money laundering scheme. The film veers from one bizarre plot situation to another, with a cast that is all over the exploitation shop (Robert Ginty; ‘The Hammer’ himself; Jess Hahn; Gordon Mitchell; queen of 80s kitsch Belinda Mayne, whose other leading roles in a motion picture include Ciro Ippolito’s Alien 2 and Edmund Purdom’s Don’t Open Till Christmas; and Mirella Banti, who most cult film fans will remember as Mirella D’Angelo’s busty lover in Dario Argento’s Tenebre, 1982). There is also some meaty action – including a scene, trimmed from many previous home video releases of the film, in which Ginty shows his Exterminator chops by dispatching some bad dudes with a co-opted chainsaw – and very bizarre scripting/production decisions. The most notable of these is the uncomfortable incestuous subplot which the film returns to almost fetishistically, Bo lusting – and occasionally, it has to be said, subtly ‘grooming’ – his sister Ingrid, then embarking on a sweaty affair with former prostitute Olga, whose resemblance to Bo’s sister is consolidated when Bo and Sam talk her into plastic surgery so she can masquerade as Ingrid in the plot to steal the White Fire diamond. The latter, in particular, seems to negate many of the filmmakers’ most obvious attempts to titillate their audience: even the most hardcore male chauvinist will find it hard to get excited at scenes featuring a nude Belinda Mayne – scenes that are clearly intended to excite the imagined heterosexual male viewer – knowing that her character is being ogled by her brother(!) Critique: An international co-production between companies based in at least four (count ‘em) NATO countries, White Fire (aka Vivre pour survivre) feels for all intents and purposes like a huge tax write-off, or one of those pop-up, always-empty businesses in your neighbourhood that everyone insists is a money laundering scheme. The film veers from one bizarre plot situation to another, with a cast that is all over the exploitation shop (Robert Ginty; ‘The Hammer’ himself; Jess Hahn; Gordon Mitchell; queen of 80s kitsch Belinda Mayne, whose other leading roles in a motion picture include Ciro Ippolito’s Alien 2 and Edmund Purdom’s Don’t Open Till Christmas; and Mirella Banti, who most cult film fans will remember as Mirella D’Angelo’s busty lover in Dario Argento’s Tenebre, 1982). There is also some meaty action – including a scene, trimmed from many previous home video releases of the film, in which Ginty shows his Exterminator chops by dispatching some bad dudes with a co-opted chainsaw – and very bizarre scripting/production decisions. The most notable of these is the uncomfortable incestuous subplot which the film returns to almost fetishistically, Bo lusting – and occasionally, it has to be said, subtly ‘grooming’ – his sister Ingrid, then embarking on a sweaty affair with former prostitute Olga, whose resemblance to Bo’s sister is consolidated when Bo and Sam talk her into plastic surgery so she can masquerade as Ingrid in the plot to steal the White Fire diamond. The latter, in particular, seems to negate many of the filmmakers’ most obvious attempts to titillate their audience: even the most hardcore male chauvinist will find it hard to get excited at scenes featuring a nude Belinda Mayne – scenes that are clearly intended to excite the imagined heterosexual male viewer – knowing that her character is being ogled by her brother(!)

Director Jean-Marie Pallardy, who has a cameo in this film as Bo and Ingrid’s father in the opening sequence, was an experienced filmmaker by the time he made White Fire. After writing and directing his debut feature L’insatisfaite in 1972, Pallardy (apparently a former male model) made numerous sex films, both softcore and hardcore, with the likes of cult film actresses such as Brigitte Lahaie, Ajita Wilson, Willeke van Ammelrooy, Marilyn Jess and Alice Arno. A number of Pallardy’s films, such as Emmanuelle 3 (1980) – one of two unofficial Emmanuelle films that Pallardy directed in 1980 – featured Pallardy in leading or secondary roles. A stand-out in Pallardy’s career, perhaps for the all the wrong reasons, is his bizarre reworking of Homer’s Odyssey: L’amour chez les poids lourds (Erotic Encounters/Truck Stop, 1980) reimagines Odysseus as a French truck-driver trying to get home to his wife Pamela. It’s as strange as it sounds. Director Jean-Marie Pallardy, who has a cameo in this film as Bo and Ingrid’s father in the opening sequence, was an experienced filmmaker by the time he made White Fire. After writing and directing his debut feature L’insatisfaite in 1972, Pallardy (apparently a former male model) made numerous sex films, both softcore and hardcore, with the likes of cult film actresses such as Brigitte Lahaie, Ajita Wilson, Willeke van Ammelrooy, Marilyn Jess and Alice Arno. A number of Pallardy’s films, such as Emmanuelle 3 (1980) – one of two unofficial Emmanuelle films that Pallardy directed in 1980 – featured Pallardy in leading or secondary roles. A stand-out in Pallardy’s career, perhaps for the all the wrong reasons, is his bizarre reworking of Homer’s Odyssey: L’amour chez les poids lourds (Erotic Encounters/Truck Stop, 1980) reimagines Odysseus as a French truck-driver trying to get home to his wife Pamela. It’s as strange as it sounds.

Amidst the likes of Une femme speciale (1979), Penetrations mediterraneennes (1980) and Body-body a Bangkok (1981), Pallardy had worked on at least one thriller/action film prior to White Fire. Like White Fire, The Man from Chicago (1975), another co-production, was lensed in Turkey; Pallardy co-directed this feature with Sohban Kologlu and Stepan Melikyan, and it also starred Jess Hahn and Gordon Mitchell, both of whom crop up in Pallardy’s body of work a number of times. There are rough parallels, if one wishes to draw them, between Pallardy’s career and those of roughly contemporaneous filmmakers such as Jess Franco and Joe D’Amato – but Pallardy’s pictures have neither the visual sensibility and Bataille-esque skirting of taboos associated with D’Amato’s best films, nor Franco’s jazz-like ability to weave a filmmaking jam out of a grab bag of performances, locations and seemingly disparate ideas. Amidst the likes of Une femme speciale (1979), Penetrations mediterraneennes (1980) and Body-body a Bangkok (1981), Pallardy had worked on at least one thriller/action film prior to White Fire. Like White Fire, The Man from Chicago (1975), another co-production, was lensed in Turkey; Pallardy co-directed this feature with Sohban Kologlu and Stepan Melikyan, and it also starred Jess Hahn and Gordon Mitchell, both of whom crop up in Pallardy’s body of work a number of times. There are rough parallels, if one wishes to draw them, between Pallardy’s career and those of roughly contemporaneous filmmakers such as Jess Franco and Joe D’Amato – but Pallardy’s pictures have neither the visual sensibility and Bataille-esque skirting of taboos associated with D’Amato’s best films, nor Franco’s jazz-like ability to weave a filmmaking jam out of a grab bag of performances, locations and seemingly disparate ideas.

White Fire has the structure and rhythm of one of its writer-director’s porno pictures – a series of narrative plateaux punctuated by bursts of action. (To be fair, some of Pallardy’s hardcore films – such as Penetrations mediterraneennes and Body-body a Bangkok pretty much dispensed with any sense of storytelling altogether.) This action, when it comes, is for the most part pretty good – such as the aforementioned chainsaw fight between Ginty and some goons, or the climactic gun battle that takes place near the cave where the White Fire diamond is located. Even this, however, sometimes becomes absurd: the chainsaw fight ends with Ginty hurling a boathook with such strength that it penetrates the sternum of one of Sophia’s henchmen. Unfortunately, what transpires in between these moments is ludicrous – even for a movie that seems so indebted to a lurid Mickey Spillane-esque comic book sensibility. White Fire has the structure and rhythm of one of its writer-director’s porno pictures – a series of narrative plateaux punctuated by bursts of action. (To be fair, some of Pallardy’s hardcore films – such as Penetrations mediterraneennes and Body-body a Bangkok pretty much dispensed with any sense of storytelling altogether.) This action, when it comes, is for the most part pretty good – such as the aforementioned chainsaw fight between Ginty and some goons, or the climactic gun battle that takes place near the cave where the White Fire diamond is located. Even this, however, sometimes becomes absurd: the chainsaw fight ends with Ginty hurling a boathook with such strength that it penetrates the sternum of one of Sophia’s henchmen. Unfortunately, what transpires in between these moments is ludicrous – even for a movie that seems so indebted to a lurid Mickey Spillane-esque comic book sensibility.

So what of that icky relationship between Bo and Ingrid? The bond between the pair is established in the film’s opening sequence, in which the couple – as children – are pursued through woodland by soldiers, their father and mother killed in front of them. (Their father is actually cooked to a crisp by a soldier who is wielding a flamethrower.) They are rescued at the last minute by Sam, and a cut to a city skyline is accompanied by an onscreen title that tells us that we have been taken to ‘Istambul [sic] – Turkey. 20 Years Later’. The now-adult Ingrid enters a high tech facility – later revealed to be the headquarters of the mining operation for which she works. The metallic sheen of the walls and furnishings, and the lift with its sliding glass doors and primary coloured lights, is meant to impress, but the set is a rickety as that of a mid-1970s Doctor Who serial. As Ingrid passes a room, she glances into it and sees a man being tortured; this is violence sanctioned and enacted by a shadowy corporation, not the state. ‘You want him telling everyone about this? What’s one lousy life for the White Fire diamond?’, Yilmaz asks Ingrid after she witnesses the security officer killing the mine worker who discovered the White Fire diamond. Greed kills. So what of that icky relationship between Bo and Ingrid? The bond between the pair is established in the film’s opening sequence, in which the couple – as children – are pursued through woodland by soldiers, their father and mother killed in front of them. (Their father is actually cooked to a crisp by a soldier who is wielding a flamethrower.) They are rescued at the last minute by Sam, and a cut to a city skyline is accompanied by an onscreen title that tells us that we have been taken to ‘Istambul [sic] – Turkey. 20 Years Later’. The now-adult Ingrid enters a high tech facility – later revealed to be the headquarters of the mining operation for which she works. The metallic sheen of the walls and furnishings, and the lift with its sliding glass doors and primary coloured lights, is meant to impress, but the set is a rickety as that of a mid-1970s Doctor Who serial. As Ingrid passes a room, she glances into it and sees a man being tortured; this is violence sanctioned and enacted by a shadowy corporation, not the state. ‘You want him telling everyone about this? What’s one lousy life for the White Fire diamond?’, Yilmaz asks Ingrid after she witnesses the security officer killing the mine worker who discovered the White Fire diamond. Greed kills.

Bo and Ingrid have been a team since childhood, though if they’ve settled in Istanbul, quite why they have excluded all others – apart from Sam, their rescuer – to such an extent is an enigma. ‘Twenty years ago, this world became a lonely place for you and me’, the adult Bo reminds Ingrid, ‘All we got is each other’. At this point, it seems more like Bo is ‘grooming’ Ingrid than consoling her. Shortly afterwards, we see Ingrid skinny dipping in Sam’s pool. She is interrupted by Bo, who leers at her body and creepily tells her ‘You certainly don’t look like anybody’s kid sister anymore [….] It’s a pity you’re my sister’. Ingrid hides her modesty with a towel, which Bo rips away in a gesture which is intended to be playful but which registers as deeply sleazy – and not in a good way.  When Ingrid is killed by Sophia and Barbossa’s thugs, Bo is inconsolable. He goes to a bar to drown his sorrows and meets Olga. Returning with Olga to Sam’s place, Bo recognises Olga as looking somewhat similar to Ingrid; this fact also strikes Sam. Bo and Sam decided to make Olga’s resemblance to Ingrid more pronounced by sending her to underground plastic surgeon Champi Doré. Following the surgery, Bo also spends considerable time ‘training’ Olga to look and behave like Ingrid. ‘What is it with this sister of yours?’, Olga asks exasperatedly in response to Bo’s stories of his sister, ‘Was she some kind of saintly genius or something?’ Bo and Olga/Ingrid grow closer and become involved in an icky sexual relationship, though Bo pulls away from this to Olga’s protestations. ‘I’m free from my past’, she tells him, ‘Why don’t you free yourself from yours?’ The pair kiss, and Bo tells Olga/Ingrid, ‘Ingrid, I love you’. (To make these love scenes more uncomfortable, there are intermittent brief flashbacks to a chaste kiss between the two siblings, as children, from the film’s opening sequence.) When Ingrid is killed by Sophia and Barbossa’s thugs, Bo is inconsolable. He goes to a bar to drown his sorrows and meets Olga. Returning with Olga to Sam’s place, Bo recognises Olga as looking somewhat similar to Ingrid; this fact also strikes Sam. Bo and Sam decided to make Olga’s resemblance to Ingrid more pronounced by sending her to underground plastic surgeon Champi Doré. Following the surgery, Bo also spends considerable time ‘training’ Olga to look and behave like Ingrid. ‘What is it with this sister of yours?’, Olga asks exasperatedly in response to Bo’s stories of his sister, ‘Was she some kind of saintly genius or something?’ Bo and Olga/Ingrid grow closer and become involved in an icky sexual relationship, though Bo pulls away from this to Olga’s protestations. ‘I’m free from my past’, she tells him, ‘Why don’t you free yourself from yours?’ The pair kiss, and Bo tells Olga/Ingrid, ‘Ingrid, I love you’. (To make these love scenes more uncomfortable, there are intermittent brief flashbacks to a chaste kiss between the two siblings, as children, from the film’s opening sequence.)

Worth mentioning is Champi Doré’s island retreat, which is like something out of a Matt Helm movie or Our Man Flint (Gordon Douglas, 1966). The clinic/complex itself is decked out with stone columns, and Doré surrounds herself with a harem of young women who dress solely in colourful, semi-transparent negligees that wouldn’t look out of place in one of Jean Rollin’s vampire films. Doré seems to be a misandrist. When Noah arrives at her clinic looking for information about Olga’s transformation into Ingrid, Champi rages at him comically: ‘You filth! You will defile with your filthy masculinity. You are…’ Noah interrupts her, ‘Yes, yes. I know. Another time we’ll discuss your views on heterosexuality. But right now, I wanna know where the girl is’. This line epitomises the film’s outrageously – in fact, comically – chauvinistic worldview, which it’s tempting to read as ironic – but which almost certainly isn’t.

Video

It seems that White Fire has been released on home video in a number of edits of various lengths, some as short as 80-85 mins (the US VHS release from Trans World Entertainment ran for 91 mins; the UK PAL videocassette release from VTS, on VHS and Betamax, ran for 81 mins). This Blu-ray release from Arrow Video contains what seems to be the most complete version of the film, with a running time of 101:49 mins. Admittedly, at this length the film drags slightly, though the shorter cuts of the film that have previously been available on VHS/Betamax omit or trim many of the more memorable action scenes – which, arguably, are the meat and veg of the film. It seems that White Fire has been released on home video in a number of edits of various lengths, some as short as 80-85 mins (the US VHS release from Trans World Entertainment ran for 91 mins; the UK PAL videocassette release from VTS, on VHS and Betamax, ran for 81 mins). This Blu-ray release from Arrow Video contains what seems to be the most complete version of the film, with a running time of 101:49 mins. Admittedly, at this length the film drags slightly, though the shorter cuts of the film that have previously been available on VHS/Betamax omit or trim many of the more memorable action scenes – which, arguably, are the meat and veg of the film.

Taking up approximately 30Gb on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, Arrow Video’s presentation is in 1080p using the AVC codec. The presentation is in the 1.78:1 ratio, which sometimes seems a little tight along the vertical axis – with the tops of actors’ heads being lopped off uncomfortably by the framing. (See some of the screen grabs for examples of this.) The film’s cited cinematographer, Roger Fellous, was experienced in his role at the time of production, so whether this is the result of sloppy second unit photography, the source material provided for this release or something else entirely is open to question. The film was shot on 35mm colour stock. Arrow’s promotional material doesn’t cite a specific source, and the presentation seems to vary somewhat – particularly in terms of contrast levels, with some scenes having a raw and flat low-contrast appearance which jars with the bulk of the presentation, most of which features some very well-balanced contrast levels – nice, clean midtones, balanced highlights and a good curve into the toe. This might suggest that the presentation of this most complete edit of the film has been composited from more than one source. Detail is for the most part very good though, again, some scenes far better than others. Damage is minimal, though a few scenes feature density fluctuations in the emulsions which are noticeable in blocks of solid colour (eg, shots of blue skies). Colour is very good, with naturalistic skintones and a sense of depth to the tones and hues.

Some full-sized screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

Audio is presented in English, via a LPCM 2.0 track, and in French, via a LPCM 1.0 track. The French and English language versions differ in a significant number of ways, conversation having subtly different connotations in each. In the French variant, Bo is instead named Mike. Most of the leads are native English speakers, though dialogue seems post-synched throughout, so neither track may necessarily be considered ‘definitive’. The English track is a little richer, with a greater sense of depth. It is accompanied by optional English HoH subtitles. The French track is a little ‘thin’, on the other hand, with optional English subtitles translating the French dialogue.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary by film critic Kat Ellinger. Commentator Kat Ellinger approaches the film with a dry sense of humour, acknowledging its shortcomings whilst also highlighting how entertaining it can be if approached in an appropriate frame of mind. (She suggests taking a shot each time Ginty’s character looks at his sister, erm, inappropriately.) - ‘Enter the Hammer’ (11:35). This interview with ‘The Hammer’ opens with Williamson talking about how important ‘presence’ is in terms of performing in action movies. Williamson discusses his feelings about Hollywood, and how he contributed to the selling and marketing of his films in Europe – despite claims in Hollywood that European distributors weren’t interested in films with black leads. ‘In America, I’m a “black actor”; in Europe, I’m an action star’, he asserts. He suggests that American distributors are (or were) fixated on Williamson’s ethnicity, whereas overseas distributors saw this as a non-issue. Williamson also discusses the logistics of making an action film. He also talks about Ginty’s career, describing Ginty as ‘an actor who never really found an image’. ‘My goal is to sustain my image’, Williamson says, arguing that he doesn’t go out looking for money – but money comes from his commitment to ‘sustaining an image’.

- ‘Surviving the Fire’ (22:27). Actor Jean-Marie Pallardy talks about White Fire. He suggests that his films were never explicit. (The evidence might suggest otherwise.) Later, he concedes that he made four hardcore pictures (against the 12 softcore sex films he directed). He talks about his collaboration with Brigitte Lahaie. He says that he ‘ripped up’ a ‘lucrative contract for 47 [presumably hardcore] movies’. Pallardy discusses at length the production of The Man from Chicago, the success of which led him to realise that it was more lucrative to shoot films in English than in French. He talks about how White Fire was cast: the English producer offered him Robert Ginty, and Pallardy met Williamson in the US. The international funding for the film fell into place because of the cast (Ginty, Williamson, Scott, Hahn, Belinda Mayne). He also reveals that Williamson helped him direct some of the action scenes. Pallardy insists, unconvincingly it has to be said, that the subtext of incest doesn’t exist in his script. (This feels like a case of protesting too much, to be fair.) This interview is in French, with optional English subtitles. - ‘Diamond Cutter’ (20:51). Bruno Zincone, the film’s editor, talks about his role. He reflects on how he came to be a film editor and talks about his journey through the film industry. He discusses how he met Pallardy and talks about the director’s predeliction for thrillers. Zincone discusses his work for Pallardy: as Zincone didn’t want people to know he had edited erotic films, Zincone adopted the pseudonym ‘Camille Scissorgold’ for these pictures. ‘Doing that kind of thing was nothing to brag about’, Zincone argues, ‘It was very funny, though’. Zincone was on the set of White Fire to offer advice with an eye on the film’s editing – advising Pallardy to shoot B roll and pick-up shots (eg, CUs of hands, and so on) that could be used as inserts in order to assist in assembling certain scenes. Zincone suggests that Pallardy’s approach to filmmaking is undisciplined – that Pallardy doesn’t like to use call sheets or work to schedule – and that Zincone’s presence on set often forced Pallardy to think ahead a little more carefully. This interview is in French, with optional English subtitles. - 2020 reissue trailer (2:12).

Overall

Unintentionally camp, White Fire is enlivened by the action sequences that punctuate its narrative. Some of these are quite gruesome: there is a particularly memorable bisection-by-bandsaw, from the groin to the torso. As noted above, even the film’s most base attempts at titillating its audience – something which one would think Pallardy would excel at, given his background in erotica/porno features – are undercut by the icky underpinning incestuous desire that Bo has for his sister Ingrid. Having Olga undergo plastic surgery in order to masquerade as Ingrid seems like Pallardy’s attempt at forging a ‘get out’ clause for bringing his male and female leads together… but it doesn’t work. In fact, it perhaps makes this relationship even more uncomfortable. Certainly, White Fire is a film which depends on the kindness of its audience. It would be difficult to find a fan of the film who doesn’t approach it with a heavy dose of irony. ‘It’s a bad film… that’s good’, Williamson confesses in the interview with him that’s on this disc, and it’s hard not to agree with him. Unintentionally camp, White Fire is enlivened by the action sequences that punctuate its narrative. Some of these are quite gruesome: there is a particularly memorable bisection-by-bandsaw, from the groin to the torso. As noted above, even the film’s most base attempts at titillating its audience – something which one would think Pallardy would excel at, given his background in erotica/porno features – are undercut by the icky underpinning incestuous desire that Bo has for his sister Ingrid. Having Olga undergo plastic surgery in order to masquerade as Ingrid seems like Pallardy’s attempt at forging a ‘get out’ clause for bringing his male and female leads together… but it doesn’t work. In fact, it perhaps makes this relationship even more uncomfortable. Certainly, White Fire is a film which depends on the kindness of its audience. It would be difficult to find a fan of the film who doesn’t approach it with a heavy dose of irony. ‘It’s a bad film… that’s good’, Williamson confesses in the interview with him that’s on this disc, and it’s hard not to agree with him.

Arrow Video’s Blu-ray release contains what seems to be the longest version of the film, which fans will relish. The presentation is for the most part very good, with a few scenes that feature footage of a slightly lesser visual quality – presumably owing to the available materials. The contextual material is very good – particularly the interviews with Pallardy (I’d love to see a longer, more substantial interview or documentary about this figure), Williamson (whose comments about how he has sustained his career as an actor are particularly illuminating) and Zincone. Please click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|