|

|

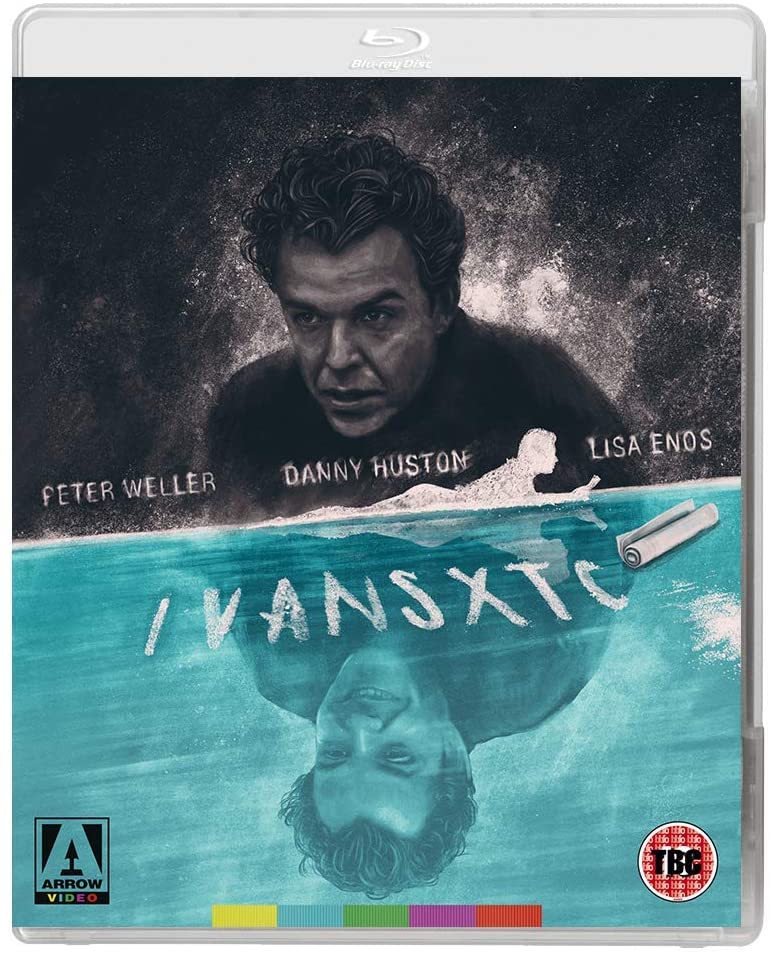

Ivansxtc AKA Ivans xtc. (To Live and Die in Hollywood) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (24th December 2020). |

|

The Film

Ivans xtc. (Bernard Rose, 2000)  Very loosely based on Leo Tolstoy’s 1886 novel The Death of Ivan Ilyich, Bernard Rose’s Ivans xtc. was the second Tolstoy adaptation by the director, following his 1997 version of Anna Karenina. Rose’s career is an interesting one. After working in television (including with Jim Henson on The Muppet Show), Rose’s first feature film was the memorable fantasy-horror Paperhouse (1988). In ’92, he made Candyman (see our review of the Arrow Video Blu-ray release of that film here), adapting Clive Barker’s short story ‘The Forbidden’ (from the fifth volume of The Books of Blood) about a council estate in Liverpool. Rose’s Candyman relocated the narrative of ‘The Forbidden’ to the Cabrini-Green Homes in Chicago; Rose’s film became, at least in its early scenes, a sort of ‘yuppie in peril’ picture of the kind where white middle-class people find themselves in a neighbourhood whose ethnic diversity becomes for them associated with danger. However, Rose’s approach to the film, and the superb performances by Tony Todd and Virginia Madsen, expanded this and turned the finished picture, taken in toto, into a story about the legacies of inequality and persecution. Very loosely based on Leo Tolstoy’s 1886 novel The Death of Ivan Ilyich, Bernard Rose’s Ivans xtc. was the second Tolstoy adaptation by the director, following his 1997 version of Anna Karenina. Rose’s career is an interesting one. After working in television (including with Jim Henson on The Muppet Show), Rose’s first feature film was the memorable fantasy-horror Paperhouse (1988). In ’92, he made Candyman (see our review of the Arrow Video Blu-ray release of that film here), adapting Clive Barker’s short story ‘The Forbidden’ (from the fifth volume of The Books of Blood) about a council estate in Liverpool. Rose’s Candyman relocated the narrative of ‘The Forbidden’ to the Cabrini-Green Homes in Chicago; Rose’s film became, at least in its early scenes, a sort of ‘yuppie in peril’ picture of the kind where white middle-class people find themselves in a neighbourhood whose ethnic diversity becomes for them associated with danger. However, Rose’s approach to the film, and the superb performances by Tony Todd and Virginia Madsen, expanded this and turned the finished picture, taken in toto, into a story about the legacies of inequality and persecution.

In the mid/late 1990s, Rose made a couple of period pictures: the Beethoven biopic Immortal Beloved (1994) and the aforementioned adaptation of Anna Karenina. With Ivans xtc. Rose took another novel by Tolstoy and dragged it into present-day America, also taking inspiration from the then-recent suicide of Hollywood agent Jay Moloney. As an agent within the Creative Artists Agency, Moloney represented a number of major talents in Hollywood filmmaking; but he spiralled into drug addiction after becoming hooked on painkillers following a bout of open heart surgery, and Moloney hanged himself in November, 1999, at the age of 35. Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich is about a high court judge (the titular Ivan Ilyich); the novel begins with Ilyich’s death, and focuses on the reactions to his death by his associates -mostly self-serving and disinterested in Ilyich’s passing. From here, the narrative moves back in time and explores Ilyich’s life – and the story leaves us with the impression that Ilyich, though successful in his career, was a man who didn’t truly experience ‘life’ and had little connection with his fellow human beings, other than through his work. It’s a novel about death and how it hangs over us all, and also about life and the tragedy of a life that has never truly been lived.  Rose’s film adaptation updates the narrative of Tolstoy’s novel to Los Angeles in the present day, and makes the protagonist, Ivan Beckman (Danny Huston), a Hollywood agent. (Ivan is a fusion of Ilyich and Moloney.) Everything else is pretty much the same – particularly the narrative structure, which begins with Ivan’s lonely death, examines his colleagues’ responses to the news of his passing, and then looks at Ivan’s equally lonely life as an agent. Rose’s film adaptation updates the narrative of Tolstoy’s novel to Los Angeles in the present day, and makes the protagonist, Ivan Beckman (Danny Huston), a Hollywood agent. (Ivan is a fusion of Ilyich and Moloney.) Everything else is pretty much the same – particularly the narrative structure, which begins with Ivan’s lonely death, examines his colleagues’ responses to the news of his passing, and then looks at Ivan’s equally lonely life as an agent.

Ivans xtc. opens with a voiceover (by Danny Huston, in character as Ivan) which relates to the film’s viewer a story of an ‘incredible pain’ that ‘wouldn’t go away’: ‘So I tried to find one image, one worthwhile image, that would take the pain away. I couldn’t find shit […] I couldn’t find one goddamned thing’. This moment of dialogue, delivered as narration, is actually taken from much later in the film; but it anchors much of what follows, in terms of highlighting the emptiness of Ivan’s life – how it is busy and filled with moments, none of which really matter. On the soundtrack, Rose makes frequent use of the prelude from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, which memorably swells underneath the film’s opening montage of Los Angeles in the early morning light. The camera takes us inside Ivan’s home – a mass of papers, books, CDs, old tech and new gadgets intermingling; modern furnishings; groaning offscreen. The use of Wagner’s music gives the film a sense of grace and scale. With these opening moments (the narration, the deserted streets, Wagner), we know immediately we are going to watch the story of a life of emptiness and excess. (The overall effect is not dissimilar to the opening of Tinto Brass’ Caligula – Caligula/Malcolm McDowell’s narration, the shots of the forest, the use of Profokiev’s Peter and the Wolf on the soundtrack.)  Ivan is admitted to hospital, apparently dying. However, his colleagues aren’t concerned about his health, simply taking his absence as an opportunity to stab him in the back. Ivan, it seems, is ‘totally fucking up’ (in the words of his assistant, Lucy). When the inevitable happens and Ivan passes away, his colleagues attribute his death to his reputation as a consumer of vast quantities of drugs. However, it seems that Ivan, an avowed non-smoker, died of lung cancer. (‘He was a drug addict and a pussy freak, and you’re telling me he died of cancer?’, one character asks in disbelief.) Ivan is also a workaholic, and owing to the demands of his job, and the neediness of his clients, seemingly cannot afford to be otherwise: in the scenes in which he is shown with his doctor, undergoing diagnosis tests, he is constantly on the telephone – either to his office or his clients – despite his doctor telling him to hang up. Ivan is admitted to hospital, apparently dying. However, his colleagues aren’t concerned about his health, simply taking his absence as an opportunity to stab him in the back. Ivan, it seems, is ‘totally fucking up’ (in the words of his assistant, Lucy). When the inevitable happens and Ivan passes away, his colleagues attribute his death to his reputation as a consumer of vast quantities of drugs. However, it seems that Ivan, an avowed non-smoker, died of lung cancer. (‘He was a drug addict and a pussy freak, and you’re telling me he died of cancer?’, one character asks in disbelief.) Ivan is also a workaholic, and owing to the demands of his job, and the neediness of his clients, seemingly cannot afford to be otherwise: in the scenes in which he is shown with his doctor, undergoing diagnosis tests, he is constantly on the telephone – either to his office or his clients – despite his doctor telling him to hang up.

In particular, the other agents are concerned about Ivan’s relationship with the spiky movie producer Don West (Peter Weller). Before his death, Ivan worked hard to bag Don for the agency, putting together a movie project based on a script by an up-and-coming writer, Danny McTeague (James Merendino). The movie was set to be Danny’s directorial debut; however, Don wanted to dump Danny from his own project, replacing him with a female director, Constanzo Vero (Valeria Golino) – an actress who has never directed, but who is rumoured to be sharing Don’s bed. As West, Peter Weller turns in a wonderfully dry performance. West is both shallow and mercurial. ‘What’d he do, freebase his face off?’, he quips when he hears of Ivan’s death, referencing Ivan’s notorious cocaine habit. Like many of those in the film who criticise Ivan’s drug habit, West is a hypocrite: in a number of scenes, we see him snorting cocaine – including, in one scene, from the thigh of a woman whilst waxing lyrical about his wife. ‘Nobody’d even piss on an agent to save him’, West adds. There’s much truth to this final sentence. Though Ivan seems to be the key mover-and-shaker behind the McTeague project, putting the various pieces of the puzzle together (only, it seems, to despair in watching them rip each other to shreds), he is regarded as a lesser human being by the likes of West.  In Ivans xtc.,Rose depicts an ideological tension in Hollywood between ‘movies’ and ‘cinema’ – and those who ally themselves with the concept of filmmaking as an industry versus those who see themselves as artists. Sitting at opposite ends of this sliding scale, McTeague and West are incompatible. ‘I’ve kind of had it with these young punks coming out of UCLA Film School’, West says angrily, ‘I’m gonna lock, load, stand up and shoot, and move on. All I want to hear from a director is “Yes”, “No” and “Move it”’. Meanwhile, the naïve McTeague cannot understand how he can be fired from the film that he wrote: ‘It’s my script. How can I be fired from my script?’, he asks upon discovering that West wants him replaced as the director of the picture. In Ivans xtc.,Rose depicts an ideological tension in Hollywood between ‘movies’ and ‘cinema’ – and those who ally themselves with the concept of filmmaking as an industry versus those who see themselves as artists. Sitting at opposite ends of this sliding scale, McTeague and West are incompatible. ‘I’ve kind of had it with these young punks coming out of UCLA Film School’, West says angrily, ‘I’m gonna lock, load, stand up and shoot, and move on. All I want to hear from a director is “Yes”, “No” and “Move it”’. Meanwhile, the naïve McTeague cannot understand how he can be fired from the film that he wrote: ‘It’s my script. How can I be fired from my script?’, he asks upon discovering that West wants him replaced as the director of the picture.

Within Ivan’s circle is his on-again, off-again lover Charlotte (Lisa Enos, who also co-wrote and produced the film). She is an aspiring writer, and we’re never completely sure whether or not her relationship with Ivan is simply a matter of convenience. She is taken aback by Ivan’s way of working, and particularly his refusal to read scripts – including that of McTeague – that he is asked to represent to potential producers. ‘You know this is shit, don’t you?’, she comments in relation to the McTeague project; but for Ivan, and for Hollywood, the quality of the script doesn’t really matter. For his part, Ivan is deeply insecure in his relationship with Charlotte, believing her to be conducting an affair with Don – in the hopes of working her way up the Hollyweird food chain. Later in the film, Ivan confronts Don about his belief that he and Charlotte have slept together; and Don warns Ivan, ‘She’s [Charlotte is] in it like every other ski pole in this town’. As the McTeague-West project builds steam and threatens to implode owing to West’s ego and McTeague’s petulance, Ivan receives news of his cancer diagnosis, and his health deteriorates. However, he doesn’t share this with anyone. When he does try to reach out to someone, calling Charlotte to ask if she will accompany him to the doctor’s office, she doesn’t give him a chance to explain. Following the diagnosis, Ivan’s behaviour becomes increasingly self-destructive. His binges on cocaine become more frequent and heavier.  In one sequence, we get a glimpse of Ivan’s past. He takes Charlotte with him to visit his father (Robert Beckman) and sister, Marcia (Joanne Duckman). Both are artists; the suggestion is that Ivan has deviated from this path, in his work in the Hollyweird film industry. Ivan’s father criticises Ivan’s choice of profession: ‘I know it’s very difficult to maintain a sense of decency in that kind of life’, he observes. Meanwhile, Marcia is cruel to Charlotte, whom she refers to as Ivan’s ‘cokehead girlfriend’. ‘Ivan, you’re gonna drown’, Marcia warns her brother – unaware of his diagnosis. On the drive back, Charlotte reacts angrily to Ivan’s passivity in the face of his sister’s spiteful comments: ‘You know I’m on anti-depressants’, she whines, ‘Why didn’t you stick up for me?’ In one sequence, we get a glimpse of Ivan’s past. He takes Charlotte with him to visit his father (Robert Beckman) and sister, Marcia (Joanne Duckman). Both are artists; the suggestion is that Ivan has deviated from this path, in his work in the Hollyweird film industry. Ivan’s father criticises Ivan’s choice of profession: ‘I know it’s very difficult to maintain a sense of decency in that kind of life’, he observes. Meanwhile, Marcia is cruel to Charlotte, whom she refers to as Ivan’s ‘cokehead girlfriend’. ‘Ivan, you’re gonna drown’, Marcia warns her brother – unaware of his diagnosis. On the drive back, Charlotte reacts angrily to Ivan’s passivity in the face of his sister’s spiteful comments: ‘You know I’m on anti-depressants’, she whines, ‘Why didn’t you stick up for me?’

Ivan takes all this – from Don, from Charlotte, from his family, from his colleagues – to such an extent that the numberplate on his vehicle should read ‘BOHICA’. As the narrative progresses, his trademark grin – quick to fire and disarming with it – becomes ever more frequent and ever more desperate. What we are left with is the memory of Ivan’s shit-eating grin, which seems permanently on his face – its protective/defensive qualities like those of a great helm – as he is built up and then knocked down again. A man’s life is falling apart.

Video

Ivans xtc. was very much influenced, photographically at least, by the Dogme 95 manifesto. With this in mind, it was shot digitally, on a Sony HDW-700A, at 60i. The intention was to give the film a documentary-style aesthetic, enhancing the verisimilitude of the story via a sense of photographic realism. The film was converted to 24fps for theatrical distribution, and theatrical prints derived from a 24fps digital internegative. Ivans xtc. was very much influenced, photographically at least, by the Dogme 95 manifesto. With this in mind, it was shot digitally, on a Sony HDW-700A, at 60i. The intention was to give the film a documentary-style aesthetic, enhancing the verisimilitude of the story via a sense of photographic realism. The film was converted to 24fps for theatrical distribution, and theatrical prints derived from a 24fps digital internegative.

The Blu-ray disc contains three different presentations of the main feature: (i) the theatrical cut, as shot in 60i, with a running time of 92:21 mins (filling 18.4Gb of space on the dual-layered Blu-ray disc); (ii) the theatrical cut, as shown in cinemas in 24fps, with a running time of 92:38 mins (filling 16.3Gb); (ii) a more recent extended producer’s cut, in 60i only, with a running time of 110:33 mins (filling 22Gb). All three presentations are in an aspect ratio of 1.78:1, which is near as dammit to the film's original theatrical aspect ratio. The 60i presentations (producer Lisa Enos’ preferred choice) are sourced from the digital files and true to what was photographed. The 24fps theatrical cut is sourced from a digital internegative that was produced from the 60i digital video files. As one might expect, the 60i presentations of both the theatrical cut and the extended producer’s cut have a sense of shuddery movement, especially in fast-moving subjects. (For example, there’s a shot of a moving car in the film’s opening montage which articulates this.) This was, of course, intentional. The 24fps presentation of the theatrical cut has a more conventional aesthetic owing to its more traditional cinematic framerate – but is not what was intended when the film was in production. (That said, the film must have been shot with the knowledge that it would be shown at 24fps in cinemas.)  All presentations betray the origins of the film as a picture shot on digital video technology of the turn of the millennium – which was, of course, intentional, and part of the film’s texture of visual realism. Highlights are often blown, and the dynamic range is compressed – in comparison with films shot on celluloid, or more recent films photographed digitally. There are no noticeable compression artifacts, and the level of detail is very pleasing. All presentations betray the origins of the film as a picture shot on digital video technology of the turn of the millennium – which was, of course, intentional, and part of the film’s texture of visual realism. Highlights are often blown, and the dynamic range is compressed – in comparison with films shot on celluloid, or more recent films photographed digitally. There are no noticeable compression artifacts, and the level of detail is very pleasing.

The 24fps theatrical cut has slightly warmer hues, with skintones veering towards red/orange, than the cool, raw digital aesthetic of the 60i presentations. The producer’s cut features newly-generated credits in a different font to the theatrical presentations. One interesting anomaly between the producer’s cut and the theatrical cut is that in the theatrical cut, the brief film-within-a-film that we see at the premiere Don West and his entourage attend, is presented in a slightly wider screen ratio than the rest of Ivans xtc. (In the producer’s cut, this film-within-a-film is presented in the same screen ratio as the rest of the feature.) Some of these aspects can be evidenced in the full-sized screengrabs at the bottom of this review, including a direct comparison between frames from the 24fps theatrical cut and the 60i producer’s cut. (Unless stated otherwise, the screengrabs throughout this review are from the 60i producer’s cut.) It’s an excellent presentation that is true to the source material. Arrow are to be commended for the options they present for the viewer.

Audio

The presentations of the theatrical cut are each accompanied by a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track. These are rich and deep, the classical music swelling on the soundtrack in the opening sequence and filling the soundscape. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included. Audio is presented via a DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 track. This is deep and rich, with good range. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included, and these are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- Theatrical Cut (in 60i) (92:21) - Theatrical Cut (in 24fps) (92:38) - Extended Producer’s Cut (60i) (110:33) - Audio commentary with co-writer/producer Lisa Enos, and Richard Wolstencraft. This commentary takes place over the extended producer’s cut of the picture. Enos and Wolstencroft talk at length about the origins of the film’s script in Enos’ experiences, and particularly the death of her mother. She says that she assembled this extended cut whilst assembling extras in preparation for the Arrow Video Blu-ray release during the Covid lockdown, ‘and it just happened’. She discusses the manner in which Rose adopted the structure of Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich. The casting is discussed in some detail, and Enos reflects on the impact of the Dogme 95 manifesto on the production. Enos is a thoughtful commentator, helping to situate the film and its narrative within the context of Hollywood. - ‘Charlotte’s Story’ (31:11). This short documentary focuses on the film’s co-writer and producer, Lisa Enos, who also plays Charlotte in the picture. Enos would collaborate (as writer and producer) with Rose on another Tolstoy adaptation, 2008’s The Kreutzer Sonata. She also produced and acted in Rose’s 2005 picture Snuff Movie. Enos talks about her role in producing and creating the film, and how the project came about. She talks about her work on documentaries before making Ivans xtc. and reflects on the decision to shoot the film on digital video. The depiction of Ivan’s experiences with the medical profession were, Enos suggests, inspired by her own experiences of her father’s sudden death from a heart attack and her mother’s ongoing treatment for cancer, which went on for five years before Enos’ mother passed away in 1997. Some of the casting choices are discussed, and Enos talks in some detail about the responses to the film, and the difficulties that the production found in getting distribution for the finished picture. There is some fascinating behind the scenes footage included too. The sound recording and audio mix are a little funky, but this is an excellent and insightful little documentary. - Egyptian Theatre Q&A (34:33). Bernard Rose, Enos, Danny Huston, Peter Weller and Adam Krentzman are featured in a Q&A recorded at a 2018 screening of the film Los Angeles’ Egyptian Theatre. They talk about the restoration of the film, and how the evolution of digital projection had by 2018 enabled the film to be shown in a form more closely related to the manner in which it had been photographed. Rose also talks at length about his approach to adapting the Tolstoy novel and condensing its lengthy narrative into a two hour running time. Weller talks about his role in great depth and playfully refuses to say on whom he based his performance as Don West – though, he suggests, ‘it’s obvious’. The participants also talk about the influence of the Dogme 95 manifesto on the approach taken during the production of Ivans xtc. - Archival Interviews: Lisa Enos (11:12); Bernard Rose (18:56). These interviews were recorded at the 2001 Santa Barbra Festival. Enos talks about her aims with the film and her focus on ‘death and dying in the modern world’ – which evolved after the passing of her own mother in 1997. Enos also discusses how the approach to making Ivans xtc. evolved from her work on documentaries. In his interview, Rose discusses the impact of Tolstoy’s work on the script, and what appealed to him about The Death of Ivan Ilyich. He talks about the manner in which the corporate structure is equivalent to slavery – and admits he is ‘appalled that people submit their lives, the only life they’ve got, to making Coca-Cola rich’, and argues that this is similar in many walks of life, not just the world of Hollywood filmmaking. - Extended Party Sequence Outtakes (41:29). These outtakes offer a glimpse of Rose’s approach to directing actors and action - Trailer (2:14).

Overall

Ivans xtc. is in danger of preaching to the converted. At the time of the film’s original release, its target audience was no doubt already swimming in the perception of Hollywood as a superficial culture where people degrade themselves in the service of money, and submerge themselves in an excess of intoxication that would kill mere mortals (or at the very least, massacre their puny proletarian bank accounts). Revisited 20 years later, in the wake of the dismantling (superficial, at least) of the Hollywood hierarchy by the #metoo movement particularly, Ivans xtc. still feels on-point. Ivans xtc. is in danger of preaching to the converted. At the time of the film’s original release, its target audience was no doubt already swimming in the perception of Hollywood as a superficial culture where people degrade themselves in the service of money, and submerge themselves in an excess of intoxication that would kill mere mortals (or at the very least, massacre their puny proletarian bank accounts). Revisited 20 years later, in the wake of the dismantling (superficial, at least) of the Hollywood hierarchy by the #metoo movement particularly, Ivans xtc. still feels on-point.

Certainly, Hollywood is depicted as a world of tyrants and sycophants, its wheels greased by insincere schmoozing. Success is dependent on popularity, which seems largely dependent on being in the right place at the right time. The vulgar language is an index of the vulgar mindsets of the filmmakers and agents: particularly Don West, who in one scene – sensing that he’s about to be stiffed on a deal (‘fucked in the ass’) – asserts that ‘An asshole’s for shitting. An asshole’s an exit wound’. Earlier, Ivan tells Don in relation to his career, ‘Don’t forget. I take it up the ass all the time’. ‘Yeah, but you don’t like it’, Don says. ‘I don’t know about that’, Ivan jokes back, shooting Don his best shit-eating grin. Integral to the film is the notion of interiority – and the idea that nobody really knows what goes on inside another person. (Though sociable, Ivan shares little about himself with other people, keeping his cancer diagnosis from his family and associates.) Arrow’s presentation of this digitally shot feature, always intended to look rough around the edges, is excellent. The inclusion of both the 24fps and 60i presentations of the theatrical cut is to be commended, as is the inclusion of the extended producer’s cut (in 60i). Added to this are some excellent contextual features – particularly the interview with Enos and her commentary for the picture. Highly recommended. Full-sized screengrabs. Please click to enlarge. Comparison of 60i producer’s cut and 24fps theatrical cut. 60i Producer’s Cut

24fps Theatrical Cut

60i Producer’s Cut

24fps Theatrical Cut

60i Producer’s Cut

24fps Theatrical Cut

60i Producer’s Cut

24fps Theatrical Cut

60i Producer’s Cut

24fps Theatrical Cut

All of the following screengrabs are from the 60i producer’s cut.

|

|||||

|