|

|

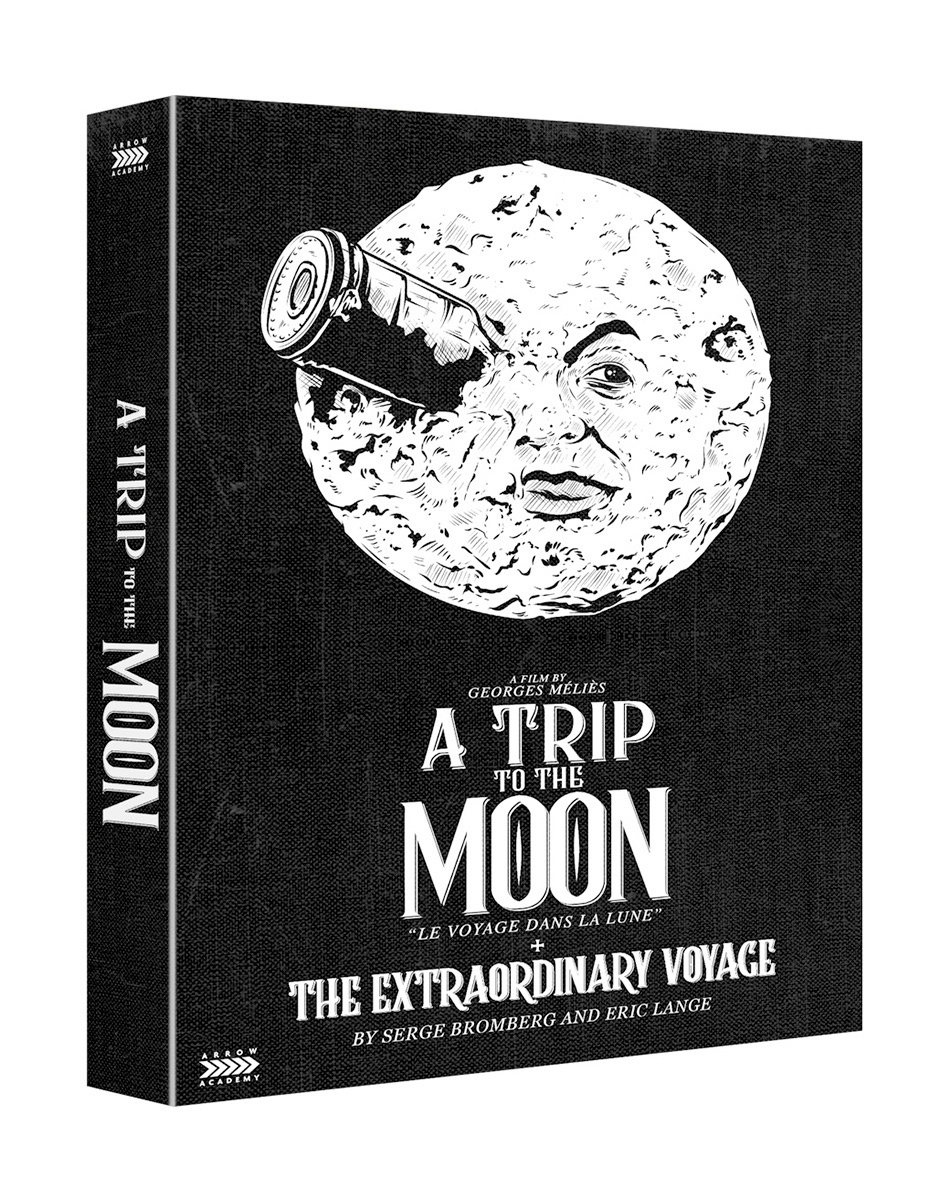

Trip to the Moon (A) AKA Le voyage dans la lune (short) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (1st January 2021). |

|

The Film

Le voyage dans la lune (Georges Méliès, 1902)  It’s difficult – or rather, impossible – to imagine a world without Georges Méliès Le voyage dans la lune (A Trip to the Moon, 1902). Its impact, in terms of its iconography and approach to narrative, has been felt so deeply in pop culture since – from popular mid-Twentieth Century movies about journeys to other worlds such as Henry Levin’s 1959 Jules Verne adaptation Journey to the Centre of the Earth and numerous films starring Doug McClure, via Terry Gilliam’s animations for Monty Python’s Flying Circus and his feature films as director, through a Smashing Pumpkins music video (‘Tonight, Tonight’, directed Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris in 1996), and into the SF subgenre and subculture of steampunk. In particular, the film’s most iconic image, that of the man in the moon with a riveted Victorian rocket ship stuck in his eye, has been quoted and referenced ad infinitum. It’s difficult – or rather, impossible – to imagine a world without Georges Méliès Le voyage dans la lune (A Trip to the Moon, 1902). Its impact, in terms of its iconography and approach to narrative, has been felt so deeply in pop culture since – from popular mid-Twentieth Century movies about journeys to other worlds such as Henry Levin’s 1959 Jules Verne adaptation Journey to the Centre of the Earth and numerous films starring Doug McClure, via Terry Gilliam’s animations for Monty Python’s Flying Circus and his feature films as director, through a Smashing Pumpkins music video (‘Tonight, Tonight’, directed Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris in 1996), and into the SF subgenre and subculture of steampunk. In particular, the film’s most iconic image, that of the man in the moon with a riveted Victorian rocket ship stuck in his eye, has been quoted and referenced ad infinitum.

La voyage dans la lune opens with a group of astronomers plotting to send a rocket to the moon. This is communicated via elements within the mise-en-scène: an abnormally long telescope, which seems cobbled together from various bits of metal tubing, and a blackboard on which the man leading the discussion draws a crude chalk drawing of the Earth and a rocket ship’s trajectory towards a smaller object (the moon). The scientists look more like wizards, with tall hats and flowing robes In the next scene, we see the building of the rocket – riveted together from sheets of metal, and looking for all intents and purposes as if it were a hollow artillery shell – as the scientists have a disagreement, communicated through some slapstick, in front of it. Once the six scientists who are to make the journey have climbed into it, the rocket is fired into space. The rocket lands on the moon – or rather, in the eye of the man in the moon. The scientists, dressed as they would on Earth (ie, as Victorian gentlemen), disembark and find a wondrous environment – one in which the weather changes rapidly and marvellous, un-Earthly sights can be seen. In a subterranean environment, they also encounter a form of extraterrestrial life: hopping, monkey-like creatures who capture the scientists and show them to their leader. Deciding to return to Earth, the scientists escape from the aliens and re-enter their rocket ship, launching it into space by toppling it off the edge of a cliff where it is balanced precariously. The ship falls through space to Earth, and the scientists return as heroes. They are greeted by a procession, and show off their prize: one of the alien creatures, who is forced to perform a dance for the gathered crowds.  Certainly, Méliès’ film was no doubt influenced by the writings of Jules Verne and others. A particular literary influence seems to have been Verne’s novel From the Earth to the Moon, which seems to have shaped Méliès’ depiction of the rocket ship and space travel. Certainly, Méliès’ film was no doubt influenced by the writings of Jules Verne and others. A particular literary influence seems to have been Verne’s novel From the Earth to the Moon, which seems to have shaped Méliès’ depiction of the rocket ship and space travel.

With his locked down camera, Méliès conjures up a variety of environments: the astronomers’ club; the building of the rocket; the launch site and the building of the cannon that will fire the rocket; the launching of the rocket; the surface of the moon and various alien environments; and finally, the return to Earth. Given the nature of the equipment used to shoot the film, each scene is a static composition; the film as a whole is a series of playful tableaux, about 30 scenes in all. The static photography is enlivened by the busy-ness of the subjects within the frame: they bustle about and seem in constant movement – arguing, gesticulating, running away from something. Inarguably, the film offers a thinly-veiled satire of colonialism. A group of ‘enlightened’ Victorian gentlemen, who can barely contain their disagreements with one another and bustle about clumsily, become determined to explore an ‘exotic’ environment (the moon). They set out on an expedition; but their very arrival disturbs the equilibrium. This is something that is so clearly symbolised in the film’s most famous shot (of the rocket ship in the eye of the man in the moon), which is so impactful because although it is profoundly absurd, we inevitably empathise with the violence enacted against the man in the moon’s eyeball and his visible wincing. (Think of the many scenes of brutality towards eyes in dramatic fiction – from the blinding of Gloucester in King Lear to the slicing of the girl’s eyeball in Bunuel and Dali’s Un chien andalou, and on to the rampant eyeball violence in Lucio Fulci’s horror films, from Zombi 2 to L’aldilà.) On their return to Earth, the scientists bring one of the ‘exotic’ aliens with them – and, as a trophy of their excursion into an ‘exotic’ territory, he/it is forced to dance at a parade. (The lively aliens, it’s said, were played by acrobats from the Folies Bergère.)  I used to show the film, and a number of other Méliès shorts, as part of a module focusing on the history of special effects in cinema. Students would come to the module often without having seen Méliès’ work before – but during the screenings would frequently comment on how familiar it seemed because they they had experienced the imagery indirectly. They also noted how funny A Trip to the Moon was, and remains. It’s in the small details: for example, the strange prosthetics on some of the human figures in the film’s early scenes, which only really become evident when you watch the film as it was intended to be seen – ie, projected on a reasonably-sized screen. Méliès’ picture is one which rewards the careful viewer. I used to show the film, and a number of other Méliès shorts, as part of a module focusing on the history of special effects in cinema. Students would come to the module often without having seen Méliès’ work before – but during the screenings would frequently comment on how familiar it seemed because they they had experienced the imagery indirectly. They also noted how funny A Trip to the Moon was, and remains. It’s in the small details: for example, the strange prosthetics on some of the human figures in the film’s early scenes, which only really become evident when you watch the film as it was intended to be seen – ie, projected on a reasonably-sized screen. Méliès’ picture is one which rewards the careful viewer.

Le voyage dans la lune was made at a point in Méliès’ career where US pioneers of cinema, including Thomas Edison, had become aggrieved by the popularity of European imports (such as the films of Méliès) and sought to put their wagons in a circle by prohibiting the importation of European moving pictures. A tension was established between US filmmaking and the rest of the world that has perpetuated ever since. At that point in his career, Le voyage dans la lune was Méliès’ most ambitious and expensive film, and it was also his longest. However, in the US duplicate prints were distributed without licence by Edison and others, an incident which led Méliès to expand his operation into America and found an office in New York. The US operation was to be managed by Méliès’ brother, Gaston, who investigated and pursued action against the US pirates of Méliès’ pictures. Sixty-seven years after the film was made, mankind did indeed land on the moon; and many were probably disappointed that it looked nothing like Méliès’ vision: no breathable atmosphere, no hopping space creatures and exotic fauna, and certainly no faces floating in the night sky. But nevertheless, Méliès was accurate in one aspect: the journey to the moon was, and continues to be, an extension of the colonial mindset.

Video

The disc includes two versions of Méliès’ film: (i) a monochrome print; and (ii) a colourised version. Both are presented in 1080p using the AVC codec, and in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.37:1. The disc includes two versions of Méliès’ film: (i) a monochrome print; and (ii) a colourised version. Both are presented in 1080p using the AVC codec, and in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.37:1.

The monochrome version runs for 12:49 mins. The colour version, thought lost for decades, was hand-painted frame-by-frame for the film’s original release. A print of this hand-colourised version was rediscovered in the early 1990s and subjected to a restoration process that took about 20 years (and was finally completed in 2010). Missing frames were patched in from the black and white version. This presentation of the film runs for 16:13 mins. (The difference in running times between the two versions seems to be down to the extra titles on the colour version explaining its restoration history.) The colour presentation is particularly interesting, and though I have seen the film numerous times before (as mentioned above, I used to show this at least once a year as part of a seminar), I’ve never seen the colour version previously. Both presentations are excellent and thoroughly film-like. There is plenty of photochemical damage throughout the two presentations – but nothing more than to be expected from a film of this vintage. The level of detail throughout both presentations is excellent, and contrast levels are pleasing – particularly in the monochrome presentation. The encode to disc does not present a problem, in the case of both presentations, and whichever version the viewer chooses, the presentations retain the structure of 35mm film.

Some large screengrabs from both versions are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

There are three audio options: (i) a new score by Robert Israel, in LPCM 2.0 stereo; (ii) piano accompaniment by Frederick Hodges, also in LPCM 2.0 stereo; and (iii) piano accompaniment by Frederick Hodges, with actors providing narration over the film, again in LPCM 2.0 stereo. If anything, Israel’s new score – containing some superb compositions – is in places a little too reverential – with the result that at times, the picture feels almost esoteric – and could perhaps do more to emphasise the humour of Le voyage dans la lune. But that’s a minor ‘gripe’ and certainly no slight against it: it’s a good score, by all means. Frederick Hodges’ piano accompaniment feels a little more in tune with the material. Whether one prefers the other will be dependent on the viewer’s tastes – but that Arrow have given us such a variety of options is laudable.

Extras

The disc includes the following: The disc includes the following:

- ‘Le grand Melies’ (31:25). This 1952 documentary by Georges Franju, a filmmaker whose sensibility was clearly in tune with that of Méliès, is presented in both its French-language and English-language variants. (The viewer is presented with the option of choosing the English or French version on the menu screen, but languages can be selected ‘on the fly’ by use of the remote control.) The French version is narrated by Méliès’ grandchild; the English version features an adult male narrator. The narration is very different in both versions. Franju, who had worked with Méliès on the unproduced Le Fantôme du metro, looks at Méliès career, reflecting through dramatized scenes, on Méliès’ significance as the cinema’s first and arguably greatest illusionist. Optional English subtitles are provided for the French version. Shot on 35mm black and white film stock, the documentary is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.37:1. - ‘The Innovations of Georges Melies’ (7:15). In a new video essay, Jon Spira looks at Le voyage dans la lune and its place within Méliès’ career. Spira highlights Méliès’ role as a pioneer of many of the methods and approaches employed within modern filmmaking. Spira talks about Méliès’ use of such techniques as in-camera dissolves, mattes, double exposures and miniatures to create his effects. - ‘The Extraordinary Voyage’ (66:14). Made in 2011 by Serge Bromberg and Eric Lange, this documentary looks at the disappearance and rediscovery of Le voyage dans la lune and its enduring impact on popular culture and filmmaking. The film focuses on the restoration of the hand-painted colour verson of the film. The documentary features numerous interviews with filmmakers – such as Costa-Gavras, Jean-Pierre Jeunet, Michel Hazanavicious and Michel Gondry – who each reflect on the importance within film history, and their own practice, of Le voyage dans la lune and Méliès’ films more generally. There is also some wonderful archival footage and clips from Méliès’ other films, along with some insightful footage from the restoration process. - 2020 Re-Release Trailer (1:05). Arrow Academy have released the film in a boxed set, limited to 1000 copies, that also includes a print version of Méliès’ 214 page autobiography, translated into English by Ian Nixon.

Overall

As stated at the outset of this review, it’s difficult to imagine a world without Le voyage dans la lune: the film’s impact has been felt so consistently, not just in cinema but in popular culture more generally. Méliès’ techniques are of course inventive and still astonishing – but it’s the deft handling of performances and the satirical tone which also linger in the mind. A soupcon of commentary about imperialism and colonialism, a dash of photographic experimentation, and a whiff of magick result in one of the most memorable viewing experiences that a cinephile can have. As stated at the outset of this review, it’s difficult to imagine a world without Le voyage dans la lune: the film’s impact has been felt so consistently, not just in cinema but in popular culture more generally. Méliès’ techniques are of course inventive and still astonishing – but it’s the deft handling of performances and the satirical tone which also linger in the mind. A soupcon of commentary about imperialism and colonialism, a dash of photographic experimentation, and a whiff of magick result in one of the most memorable viewing experiences that a cinephile can have.

Arrow Academy’s Blu-ray release of the film is stellar (if you’ll pardon the pun). Both the colour and monochrome presentations are superbly filmlike. The main feature/s are accompanied by contextual material that could easily be released separately. ‘The Extraordinary Voyage’ is an excellent documentary that looks at the restoration of Le voyage dans la lune and the film’s impact in terms of film history and the evolution of cinema. Franju’s ‘Le grand Méliès’ is equally wonderful – and a pleasure to be able to watch in both its French and English-language variants. This is a superb release – easily one of the best of the year. Full-sized screengrabs from both the monochrome and the colour presentations are below. Please click to enlarge them.

|

|||||

|