|

|

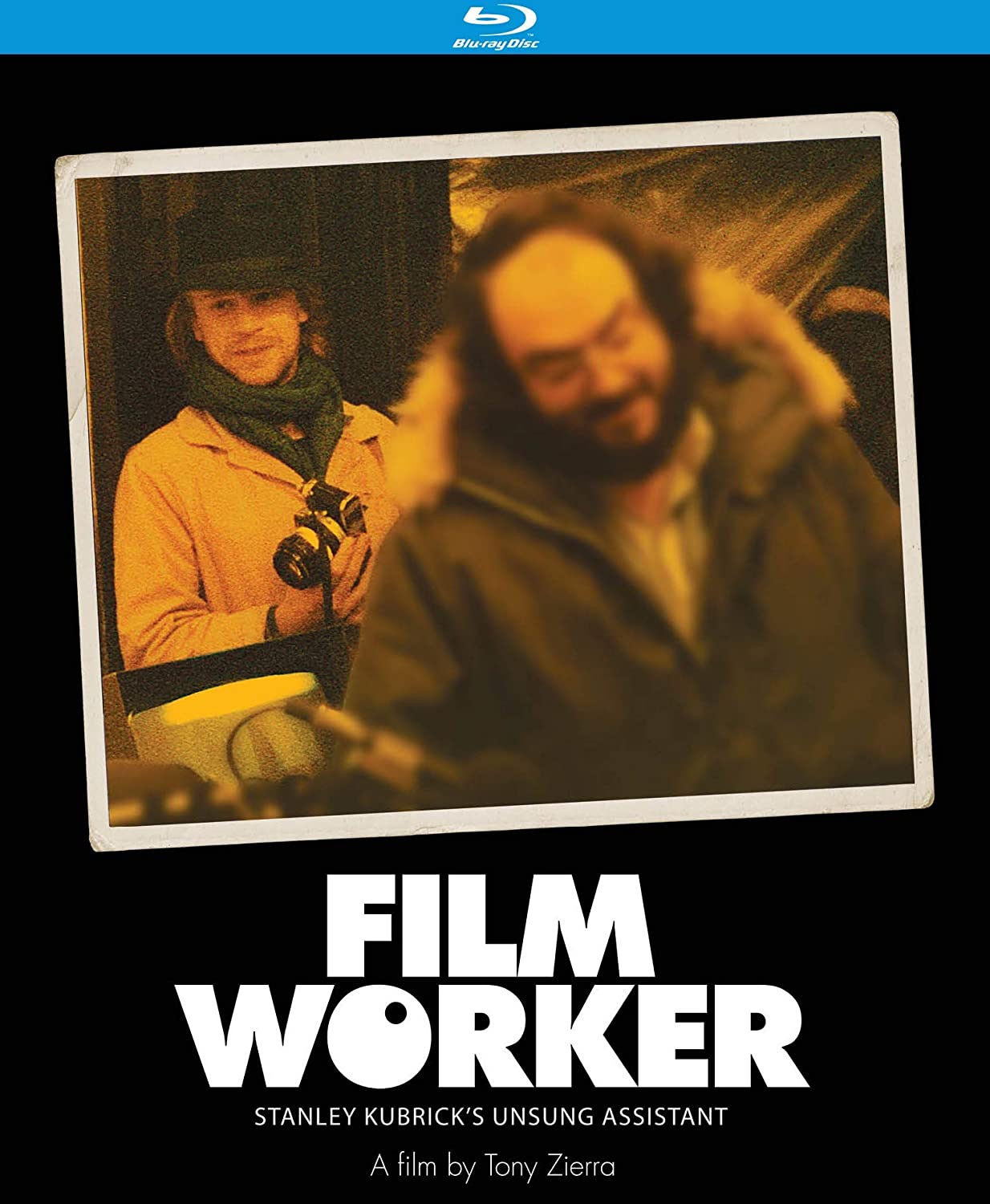

Filmworker

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray A - America - Kino Lorber Review written by and copyright: Robert Segedy (15th March 2021). |

|

The Film

"Filmworker" (2017) If you’re like me, you stay through to the end of a film as the credits roll. How often have you wondered what exactly did the Lead Grip actually do? Usually there are many names attached to a film project, from catering to casting, from locations to the music used, the names roll on by and sometimes I wonder what the ultimate reward for these people is? A name on the credits, to know that they had a small role to play to the film’s overall success and a paycheck of course, or is there perhaps more to the story? This documentary is the story of one of those people, but the director in question was undoubtedly a true genius of the Twentieth Century: Stanley Kubrick. Filmworker is the story of one man’s servitude to another’s bright shining light and in the end, we are left to ponder the question of was it worth it? This is the story of that man: Leon Vitali and in Filmworker we get the opportunity to hear his story, learn of his sacrifices, and ultimately, we are left wondering, was it all worth it? Look up the term auteur and you may find Stanley Kubrick’s name mentioned as an example of such a filmmaker. Encyclopedia Britannica defines the term as “theory of filmmaking in which the director is viewed as the major creative force in a motion picture.” Essentially think of the director as being the author of a film and whereas an auteur filmmaker leaves his imprint on the entire production. Stanley Kubrick was just such a craftsman; seeing one of his films leaves one with the understanding that Kubrick’s fingerprints are all over his films: Fear and Desire (1953), Killer’s Kiss (1955), The Killing (1956), Paths of Glory (1957), Spartacus (1960), Lolita (1962), Dr. Strangelove (1964), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), A Clockwork Orange (1971), Barry Lyndon (1975), The Shining (1980), Full Metal Jacket (1987), Eyes Wide Shut (1999). Upon seeing any one of these films, one certainly can be entertained and perhaps be impressed with the director’s vision, but as we all know, film making is hardly a one-man job. Many individuals working behind the scenes are ultimately responsible for what we see on the screen, but often the director receives the majority of the credit. Enter Leon Vitali. “If (things) was going really well, then it was a sort of magic place to be, Vitali says, “and we felt an absolutely beautiful air of excitement. And if it wasn’t going well, it could be murderous, like walking through treacle. It was a wonderful kind of up-and-down, all-embracing, emotional experience.” Vitali was a rising fixture of the Seventies British film and television scene, appearing in numerous stage and television programs, when he was cast in Stanley Kubrick’s period piece film Barry Lyndon (1975) in the role of Lord Bullington, the lead character’s stepson. Despite repeated takes and witnessing firsthand how Kubrick operated, Vitali expressed an interest in learning the craft of filmmaking; after concluding a different acting opportunity, Kubrick kept his word and made Vitali his personal assistant on The Shining (1980). Thus, beginning his career in servitude to his mentor, Stanley Kubrick. One may wonder if this opportunity was Vitali literally selling his soul to the devil. Kubrick sent Vitali a copy of Stephen King’s novel The Shining with a note that stated “Read This.” Next Kubrick called Vitali and asked him what he thought of the novel and Vitali replied that he thought that it would be interesting as a film. Kubrick dispatched Vitali to Chicago where he interviewed over five thousand children, looking for the perfect kid to portray Danny Torrance; he ultimately discovered Danny Lloyd, merely five years old at the time. Later it was Vitali who came up with the idea of using twins to play the murdered girls (Lisa and Louise Burns) to mirror the famous Diane Arbus photograph of creepy identical sisters. Testimony to Kubrick’s never-ending search for perfectionism is established during the scene with Scatman Crothers where Danny eats a bowl of chocolate ice cream: ultimately five gallons was consumed for those shots. There are plenty of lesser-known facts revealed during Filmworker that display Kubrick as a relentless perfectionist, constantly demanding re-shoots, changing angles during the film, and always being on the lookout for the moment when something miraculous occurs. Throughout the film we are shown clips with many of Kubrick’s stars commenting on Vitali’s near obsessive behavior during filming; be it Ryan O’Neal in Barry Lyndon, Matthew Modine commenting on Vitali’s absorption while making Full Metal Jacket: “What Leon did was a selfless act, a kind of crucifixion of himself” or R. Lee Ermey conspiring with Vitali to have Emery move from being a military advisor to becoming an actor himself. Rarely does one get the chance to rub shoulders with greatness as Vitali did but the cost for such closeness comes at a high price. We witness that when a clip is shown of Vitali acting in Barry Lyndon and then we cut to present day where we sort of recoil in horror as the young actor with a full head of hair is transformed into a skeletal Keith Richards look alike. Vitali is the first to acknowledge that he learned a great many things at the feel of his master: casting director, acting coach, color time processing agent, foley artist, and ultimately to this day he is still involved with the Kubrick estate, continuing to supervise transfers for all Kubrick transfers on Blu-ray, 4K and 70 mm. Director Tony Zierra is exploring the fine line between full sprung genius and conniving manipulative predator; Kubrick was clearly portrayed as both. He could be a sensitive mentor, or his moods could easily shift into a diabolical dictator, ordering take after re-take, up to thirty times, until he was satisfied. Kubrick’s ghost hovers throughout Zierra’ s film; he is captured in Vitali’s recollections, he is shown in various production stills throughout the film, but most importantly Kubrick’s sprit is present in Vitali’s memories. Ultimately one needs to question if Vitali made the correct choices in his career; possible film star who may appear in a couple of films, possibly win some awards, and receive recognition of his peers or be an individual who participated in the creation of five enduring works of art? Vitali does not hesitant to respond: “Absolutely not!” “Stanley is always there with me” he admits, “[still] saying ‘Don’t you dare.’”

Video

The picture reproduction is noticeably clear with excellent framing and picture quality. There is plenty to enjoy here with extensive interviews with actors and film industry participants who knew or worked with Stanley Kubrick and/or Leon Vitali. There is the use of some poorly executed animation at certain times that I found to be rather distracting.

Audio

The soundtrack by David Ben Shannon is ultimately unobtrusive and complementary. The Blu-ray comes equipped with English subtitles that may assist some viewers. The closing piano theme by Handel is Sarabande Fantasia is especially lovely. Roll the Credits!

Extras

Q and A with Leon Vitali and director Tony Zierra. Moderated by Rodney F. Hill. (11:00). Filmed in front of a live audience. Hosted by Rodney F. Hill, Associate Professor of Radio, Television, Film, Chair. This is a brief interview with Vitali and Zierra which focuses on how the documentary came into being and some questions from the host. Filmworker Trailer: (2:26). The Kid Stays in the Picture Trailer: (1:39).

Overall

I found this documentary to be an incredibly fascinating portrait of a man that readily accepted the role of being much more than a mere apprentice, but an acolyte to genius itself. Ultimately one leaves the film with a palpable feeling of sadness; sorrow that Kubrick is no longer with us producing his craft and a type of bittersweet sadness that Vitali has not toiled in vain.

|

|||||

|