|

|

Jug Face AKA The Pit (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (11th October 2021). |

|

The Film

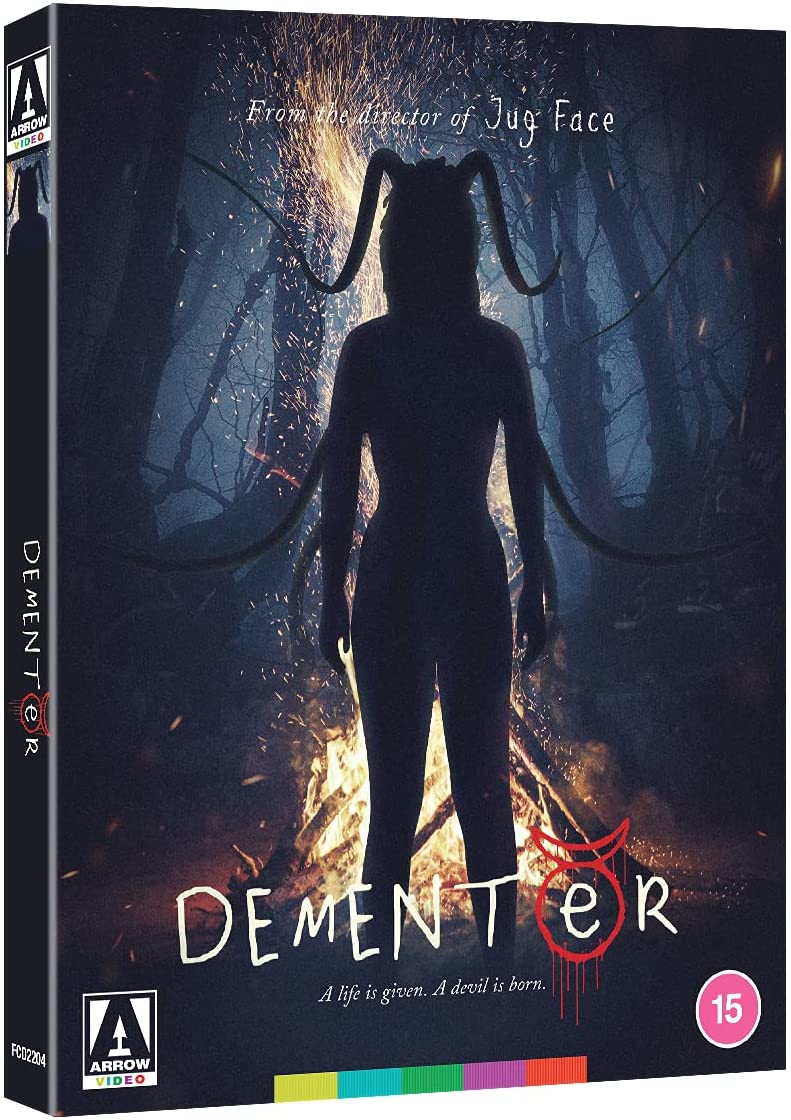

Dementer and Jug Face (Chad Crawford Kinkle, 2019)  The second feature film by independent horror filmmaker Chad Crawford Kinkle (after 2013’s Jug Face, aka The Pit), Dementer (2019) has a similarly strong sense of place, its slow-burning horror enhanced by its non-metropolitan setting – giving the film a strong regional flavour. Arrow have released Dementer on Blu-ray along with Kinkle’s feature debut, Jug Face, in a features-packed edition. The second feature film by independent horror filmmaker Chad Crawford Kinkle (after 2013’s Jug Face, aka The Pit), Dementer (2019) has a similarly strong sense of place, its slow-burning horror enhanced by its non-metropolitan setting – giving the film a strong regional flavour. Arrow have released Dementer on Blu-ray along with Kinkle’s feature debut, Jug Face, in a features-packed edition.

Dementer is the ‘A’ feature on this release, so it seems fair to discuss that picture first and most closely. The film originated in Kinkle’s desire to build a story around his older sister, Stephanie, who has Down’s Syndrome. In writing the script, Kinkle devised a narrative that could be shot around Stephanie’s daily routines. What resulted from this exercise is a plot that focuses on Katie (Katie Groshong), who is employed by Eller (Eller Hall), who manages a community hub, as an in-house carer for Stephanie and a number of other individuals with Down’s Syndrome. The film opens with a haunting montage of discordant images and sounds: a bonfire at night; a naked woman (Kate) running through a field, her body picked out by the headlights of a vehicle chasing her; a chinkling (of what sounds like a tambourine, though in the extra features on this disc Kinkle suggests it is another instrument), and ominous strings beneath it; a disembodied man’s (Larry Fessenden, the director of the superb Wendigo and The Last Winter, among others) voice counting slowly. These fragments of sights and sounds bleed into the diegetic present, as Kate is interviewed by Eller for the position of community carer for Stephanie and the others. Kate’s feet, decked in a proletarian grey pair of grey Converse trainers, shake nervously beneath the seat of the chair on which she sites. ‘I don’t sleep much anyway. That’ll be fine’, Kate responds when Eller tells her the job will require working on a shift pattern of two days on, two days off.  Kinkle built the film around Stephanie’s routines, and for much of its running time Dementer has an extraordinary cinema-verite style aesthetic: most, if not all of the scenes, seem to have been photographed on a single camera set-up, with the use of jump cuts and direct sound, together with the fact that the bulk of the performers (barring Groshong) are non-professional actors, bestowing a strong sense of naturalism on the events that unfold in the community hub and Stephanie’s house. Kinkle built the film around Stephanie’s routines, and for much of its running time Dementer has an extraordinary cinema-verite style aesthetic: most, if not all of the scenes, seem to have been photographed on a single camera set-up, with the use of jump cuts and direct sound, together with the fact that the bulk of the performers (barring Groshong) are non-professional actors, bestowing a strong sense of naturalism on the events that unfold in the community hub and Stephanie’s house.

This extraordinary naturalism is broken by expressionistic fragments of scenes that come to Katie at night – at least, initially – but increasingly during the daytime. These moments, whih bleed into the present via the use of overlapping sounds and voices, speak of Katie’s past – or what the film suggests is her past: during which she was taken by Larry (Fessenden) to an isolated house in the woods, and subjected to the teachings of Larry, a cult leader, and his entourage. (‘Your family didn’t understand you’, Larry tells her during one of these flashbacks, ‘They didn’t deserve you. You have a new family now’.) These moments of analepsis suggest that Katie escaped from the cult, somehow. However, the film’s depiction of these flashbacks is ambiguous, and it is never clear whether they are indeed a representation of the events that befell Katie prior to the start of the film’s narrative, or if they are a fantasy conjured by Katie. There are small clues to suggest the veracity of these flashbacks, including scarring on Katie’s back which seems to have originated from Larry branding her with a sigil – but nothing absolutely definitive, and the film retains a satisfying ambiguity about Katie’s past, and how it determines her actions in the present. The viewer is never completely sure whether Katie is the victim of a brainwashing cult in the woods, or if she is simply deluded and prone to paranoia and hallucinations.  In the diegetic present, Katie carries with her a journal that contains various spells (for want of a better word) taught to her by Larry. This, combined with the use of Fessenden’s disembodied voice on the audio track, suggests that within the cult, Katie was taught rituals of sacrifice. (‘For a life is given, and the devil is born’, Larry’s voice can be heard saying at one point.) When Stephanie falls ill, Katie believes it is because she has been visited by ‘the devils’, and referring to Larry’s teachings in the journal, she buys a cow’s heart and hides it under Stephanie’s bed. In the diegetic present, Katie carries with her a journal that contains various spells (for want of a better word) taught to her by Larry. This, combined with the use of Fessenden’s disembodied voice on the audio track, suggests that within the cult, Katie was taught rituals of sacrifice. (‘For a life is given, and the devil is born’, Larry’s voice can be heard saying at one point.) When Stephanie falls ill, Katie believes it is because she has been visited by ‘the devils’, and referring to Larry’s teachings in the journal, she buys a cow’s heart and hides it under Stephanie’s bed.

When Stephanie’s health worsens and Katie discovers that the cow’s heart has disappeared, Katie begins to suspect that dark forces are at work and escalating. Referring to her journal, she concludes that ‘A sacrifice will keep the devils away’. She visits an animal shelter, and adopts a cat. Taking the creature into the garden of the house in which Stephanie lives, Katie kills it with a knife and burns the body, placing the charred remains near the doorway of the house. In flashback, we see Larry feeding cats on the porch of the house in the woods. ‘Beat a cat once, and it’ll never come back’, he advises Katie, ‘Feed it, it’ll keep coming back over and over’. ‘Why so many?’, she asks. ‘I’ll teach you soon enough’, Larry responds: Katie’s actions in the present are once again directed by the Larry’s teachings in the past. Events escalate, and when the charred corpse of the cat is discovered, Katie is fired from her job. However, she returns to the house to abduct Stephanie, taking her to the woods. Believing herself to be Stephanie’s saviour, Katie’s actions instead seem directed by instincts that are much more malevolent. Though Dementer is a distinctly oppressive film, Kinkle works into the script some delicious moments of black humour. At one point, Katie’s colleague Brandy (Brandy Edmiston) asks Katie about the journal she carries with her. ‘I just write things down so I don’t forget ‘em’, Katie tells Brandy. ‘I drink every night to do exactly the opposite’, Brandy responds.  Kinkle’s debut feature, Jug Face is defined by a similarly embedded sense of the non-metropolitan quotidian, filtered through a skewed comprehension of reality that has taken root within an insular community. Kinkle’s debut feature, Jug Face is defined by a similarly embedded sense of the non-metropolitan quotidian, filtered through a skewed comprehension of reality that has taken root within an insular community.

The narrative of Jug Face predominantly takes place in an isolated rural community which consists of what seems to be no more than two families. These two families marry into one another, and the viewer presumes that given how small and insular the community is, this has been taking place for generations – resulting in layers upon layers of inbreeding. The belief system of the community around which the narrative focuses is outlined in the animated titles sequence. This depicts a frontier community and their relationship with The Pit: how it came to be worshipped and associated with disease, and the sacrificing of a Catholic priest to appease it – a victim of sacrifice picked out by a jug made (in a trancelike state by a member of the community) in the priest’s likeness. The quietly combative nature of Jug Face is established in its opening sequence, which takes place after the credits: a young man, Jessaby (Daniel Manche), pursues a young woman, Ada (Lauren Ashley Carter), through the forest, demanding sex. She initially rejects him, but eventually relents; the couple fuck aggressively against a tree near The Pit. This moment of rough coitus is cross-cut with Dawai (Sean Bridgers) sculpting a new face jug at the potter’s wheel, the juxtaposition of sex and pottery seeming intentionally to parody the famous potter’s wheel sequence of Jerry Zucker’s Ghost (1990).  Only later do we realise that the couple we saw fucking against the tree are brother and sister, and this encounter leaves Ada pregnant. Given that the community seems to be built on incest (at least, removed by a generation or so), this perhaps wouldn’t be so much of an issue within Ada’s family, other than the fact that a marriage has been arranged between Ada and Bodey Jenkin (Mathieu Whitman). Ada faces more problems when she discovers that the face jug Dawai has made in his trance, during her tryst with Jessaby, is a likeness of her. Realising this marks her as the target of the next sacrifice to The Pit, Ada hastily hides the face jug after Dawai places it in his outdoor kiln. Only later do we realise that the couple we saw fucking against the tree are brother and sister, and this encounter leaves Ada pregnant. Given that the community seems to be built on incest (at least, removed by a generation or so), this perhaps wouldn’t be so much of an issue within Ada’s family, other than the fact that a marriage has been arranged between Ada and Bodey Jenkin (Mathieu Whitman). Ada faces more problems when she discovers that the face jug Dawai has made in his trance, during her tryst with Jessaby, is a likeness of her. Realising this marks her as the target of the next sacrifice to The Pit, Ada hastily hides the face jug after Dawai places it in his outdoor kiln.

In the build-up to the wedding, Ada’s mother, Loriss (Sean Young), is obsessed with checking that Ada remains a virgin – by inspecting her daughter’s genitals. Ada tries to delay Loriss’ inspection by using red paint in her underwear to suggest that she is experiencing her period. (Given how small the community is and the disbelief that Loriss and Ada’s father, Sustin – played by Larry Fessenden – express when they realise that Jessaby and Ada have had sex with one another, one wonders who exactly it is that Loriss suspects of trying to engage in coitus with her daughter.)  It’s difficult not to see the community as an allegorical representation of the terrors of a theocratic society – complete with rigidly demarked roles for men and women. (‘It’s a woman’s job to have babies’, Sustin tells Ada, ‘You gotta be joined for that’.) To the film’s viewer, the community’s belief in the outwardly irrational connection between the manufacture of the jug faces, human sacrifice, and the supernatural powers of The Pit seems ludicrous – but has its own internal logic. What is most interesting about Kinkle’s approach to this material is that the film intimates that the bizarre, outrageous belief system of the community has some sense of grounding: this is most directly communicated in the psychic visions experienced by Ada, making her a witness to the gruesome killings of several members of the community, after she has hidden the face jug that Dawai has made in her likeness. These killings are committed by a seemingly ethereal entity, the visions that Ada experiences of these murders having something in common, aesthetically, with the racing camerawork depicting the point-of-view of the demon in Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead (1982). It’s difficult not to see the community as an allegorical representation of the terrors of a theocratic society – complete with rigidly demarked roles for men and women. (‘It’s a woman’s job to have babies’, Sustin tells Ada, ‘You gotta be joined for that’.) To the film’s viewer, the community’s belief in the outwardly irrational connection between the manufacture of the jug faces, human sacrifice, and the supernatural powers of The Pit seems ludicrous – but has its own internal logic. What is most interesting about Kinkle’s approach to this material is that the film intimates that the bizarre, outrageous belief system of the community has some sense of grounding: this is most directly communicated in the psychic visions experienced by Ada, making her a witness to the gruesome killings of several members of the community, after she has hidden the face jug that Dawai has made in her likeness. These killings are committed by a seemingly ethereal entity, the visions that Ada experiences of these murders having something in common, aesthetically, with the racing camerawork depicting the point-of-view of the demon in Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead (1982).

Both Jug Face and Dementer offer stories about seemingly irrational belief systems, and by presenting these ‘as is’ (even with some confirmation of the seemingly illogical, as in Jug Face), Kinkle undermines the surety of his audience’s understanding of the world. Both films are also anchored by a distinctly un-Hollywood approach to their subject matter, with a strong regional/rural identity: this is something particularly laudable in terms of Dementer’s marriage of expressionistic horror sequences and New Wave-esque cinema-verite style material.

Video

Both Dementer and Jug Face were captured digitally and in colour. Each film is included on a separate region ‘B’ coded disc, in a 1080p transfer using the AVC codec. Both Dementer and Jug Face were captured digitally and in colour. Each film is included on a separate region ‘B’ coded disc, in a 1080p transfer using the AVC codec.

Disc One includes Dementer. With a running time of 80:54 mins, Dementer is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.78:1 and fills 24.4Gb of space on its disc. For the bulk of its daytime footage, Dementer has a very clean, digital aesthetic: the level of detail is pleasing, and contrast levels are good, with deep blacks. Some of the daytime footage seems very slightly overexposed, presumably an artistic choice in order to emphasise the contrast between this material and the night-time footage. The juxtaposition between day and night within the film roughly correlates to the disjuncture within the narrative between present and past, the bulk of the night-time footage appearing in the expressionistic, fragmented flashbacks to Katie’s time within Larry’s cult – and the bulk of the daytime footage depicting Katie’s present-day actions with Stephanie. The ‘grit’ of the night-time footage is in stark contrast to the ‘cleanliness’ of the daytime footage. A high ISO has been used for the night-time footage, much of which seems to have been shot using available light (eg, Katie by the fire in the field) or directed light – headlamps and flashlights picking out faces in the darkness like Fresnel spotlights. As a consequence of the high ISOs used, the night-time footage has a high level of sensor noise, which looks remarkably like film grain. This gives this material a coarseness of texture. Additionally, the night-time footage features a sharp curve into the toe and crushed blacks. All of this is a deliberate artistic choice. Arrow’s HD presentation of the film is excellent, with no issues presented by the encode to disc.  Disc Two contains Jug Face. Presented in an aspect ratio of 2.35:1 (approximately), Jug Face has a running time of 81:10 mins and fills 24.5Gb of space on the disc. Disc Two contains Jug Face. Presented in an aspect ratio of 2.35:1 (approximately), Jug Face has a running time of 81:10 mins and fills 24.5Gb of space on the disc.

The bulk of Jug Face takes place during daytime, and has a similarly ‘clean’, digital aesthetic to the daytime footage of Dementer, as discussed above. Colour is consistent throughout, and skintones naturalistic. Contrast levels are evenly balanced, though the dynamic range of the camera sensor is clearly narrower than that of 35mm film. Shadow detail is present and consistent. Again, this is a compelling presentation of a shot-on-digital feature, with no issues in terms of the encode to disc. For full-sized screengrabs from both features, please scroll to the bottom of this review.

Audio

Both films are presented with the same audio options: a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track, and a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. In the case of both films, both audio tracks are very good, with a very strong sense of range. The score for Jug Face features much electric guitar fuzz, with a deliberate sense of compression at the high-end. (As a matter of fact, the score for this picture reminded me somewhat of Neil Young’s score for Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man.) The audio tracks for Dementer, at least in the flashbacks, contains some significant audio distortion (with Fessenden’s voice growling in the background). This is all deliberate, of course, and carried excellently by the tracks on this disc. Both features are accompanied by English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. These are easy to read and accurate in transcribing the films’ dialogue.

Extras

Disc One includes the following extra features: Disc One includes the following extra features:

- Dementer - An audio commentary by writer-director Chad Crawford Kinkle. This solo commentary by the film’s writer and director, Chad Crawford Kinkle, gives insight into Kinkle’s intentions with the film and his desire to build a film around his sister, Stephanie. Kinkle talks at length about the processes involved in making the picture, and attempts to situate Dementer within a broader framework of ‘extreme’ films that challenge the art/reality dualism. He also discusses the relationship between Dementer and his previous feature, Jug Face. - An audio commentary with the film’s cast and crew. This commentary features a larger number of participants: Kinkle, Katie Groshong, and cinematographer Jeff Wedding. The trio react to the film, and the conversation begins with a discussion of the film’s score, by Sean Spillane. They talk about the shooting of the picture and their shared experiences of this. It’s a lively commentary track, with some overlap with Kinkle’s solo commentary, but Groshong and Wedding provide an alternate perspective on some of the events. - An audio commentary by writer-director Chad Crawford Kinkle and critic Chris Hallock. In this commentary track, Kinkle sits with Chris Hallock, who provokes Kinkle into answering questions about the film and its production. Again, there’s some overlap between this commentary and the previous two. Arguably, three commentary tracks is a little ‘overkill’, and perhaps there could have been a way to edit this and Kinkle’s solo track together.

- ‘The Making of Dementer’ (24:27). This featurette looks at the making of Dementer and features some delicious behind-the-scenes footage of the production, alongside interviews with the cast and crew. Kinkle talks about how Dementer grew from his long-term desire to make a film with his sister, who plays Stephanie in the picture. Eventually, the film’s narrative grew in his mind, and Kinkle decided to make a film about a carer – and he wanted to tell a story involving characters who live with Down’s Syndrome, like Kinkle’s sister. Katie Groshong says that her understanding of the project, when Kinkle approached her to star in it, was that it had a loose basis in the fairy tale Hansel and Gretel; she was one of only three actors in the film who had acted in films previously. The finished film, Jeff Wedding (the film’s cinematographer), emphasises the cinema verité style of the picture. The marrying of documentary and narrative approaches was something new to Wedding. Kinkle wanted to shoot the film handheld in order to offer more flexibility, to give a ‘documentary feel’ and to enable the freedom to capture more spontaneous moments – something he regretted not capturing in Jug Face because of the more static, locked-down manner in which that picture was shot. Kinkle says that at its heart, Dementer is about social media, and the ways the influence of this can lead people to act in ways they don’t understand – with the journal that Katie consults being a symbolic representation of ‘her Twitter feed’, distorting her perception of the world, making her increasingly paranoid, and leading her to behave in outwardly bizarre ways. - ‘In the Words of Larry’ (18:28). With a carefully poised copy of Shout! Factory’s ‘The Larry Fessenden Collection’ boxed set behind him, Larry Fessenden speaks about his work on the film. He discusses how he came to be cast in the role, and talks about working with Kinkle. As a director of independently-produced horror films himself, Fessenden says he empathised with Kinkle’s desire to make a horror picture away from Hollywood, and expresses the view that filmmaking is different from other art forms because without the right resources and financial support, a filmmaker cannot continue to practise and hone their craft in the same way that a painter, for example, is able to. Consequently, Fessenden wanted to support and help Kinkle, and use his name to bring attention to the project.

Fessenden talks about his approach to acting, saying that once one has learnt one’s lines, the traits and rhythms of the character begin to emerge. He suggests that Kinkle brings a ‘Southern Gothic take’ to the stories depicting in both Dementer and Jug Face, and a visceral-ness that comes from Kinkle’s rural upbringing and his background as a hunter. Fessenden suggests that this regional specificity and ‘authenticity’ is what makes Kinkle’s work distinctive – and is something that more horror films should strive to achieve. There is a level of influence from iconic auteurs working with a greater level of resources but, Fessenden argues, ‘intelligent storytelling’ can still be achieved ‘with not a lot of money’. - ‘Outsider Art and Dementer’ (46:48). Kinkle, Fessenden, and Lucky McKee talk about outsider art, in a recorded online chat. Kinkle mentions approaching Lucky McKee with his idea for building a project around his sister, and McKee encouraged Kinkle to look at Werner Herzog’s 1970s work, and the manner in which it blurred the boundaries between acting and reality. The trio reflect on some of the difficulties involved in getting projects like Dementer funded and distributed to an audience, and the issues involved in working with family members. Fessenden, in particular, laments the demise of challenging cinema, which he suggests is ‘cathartic in the end’. - Short Films: VHS Movies (1992-1994) (6:01); ‘The Playstation’ (1995) (8:53); ‘Makeup (1998) (17:49). These shorts are provided with the option of watching each with a commentary by Kinkle. ‘VHS Movies’ is a compilation of special effects tests and horror-themed snippets that Kinkle made during his school years with three of his friends. They were shot on Kinkle’s mother’s VHS camcorder, bought for her by Kinkle’s grandparents. We see kids playing with masks, as a recurring character called ‘Microwave Man’, and Kinkle observes in the commentary that he and his friends were aiming for a Wayne’s World-style level of ‘ridiculousness’. In one clip, Kinkle is shown being shot by a friend wielding Kinkle’s BB gun, in order to set off a crude blood squib. (Kinkle’s friend in this clip provided some of the houses used in the production of Dementer.) Most of the clips are single shot takes, free from any kind of narrative, though there is a clip of a vampire (played by Kinkle) pursuing one of Kinkle’s friends through a house that offers an attempt to build some level of story through the sequencing of shots.

‘The Playstation’ (again, shot on a VHS camcorder) was made by Kinkle whilst studying a module on film editing at the Savannah College of Art and Design. The film opens with a young man lovingly stroking a mannequin that is seated in front of a television and Playstation console. In another scene, the young man is shown caressing the mannequin in the shower, and subsequently he is shown striking the mannequin on a mattress. Shot voyeuristically, with a handheld camera whose view of the scene is partially obscured by various objects in the foreground, Kinkle suggests this short was at least in part inspired by the Dogme-95 films he had seen. (He references Von Trier’s The Idiots, though that wasn’t released until 1998.) The short seems to have equal shades of influence from Buttgereit’s Nekromantik and William Lustig’s Maniac. As Kinkle says, the short is ‘too repetitive’ and goes on too long, but certainly there’s an attempt to build narrative through the accumulation of detail in the form of the young man’s relationship with the mannequin – with intimations of domestic and sexual abuse. When Kinkle showed the film in his class, the teacher and a graduate student who was assisting both criticised the film sharply whilst comparing Kinkle to Robert Crumb, and Kinkle ‘knew that I had gotten under someone’s skin’ whilst not intending to ‘do something offensive’. He realised from that experience how important getting ‘a reaction’ to his films was, and the fine line between doing this and ‘going too far in terms of dirty tricks to manipulate’ the audience. ‘Makeup’ was made as Kinkle’s final project (‘senior project’) during his days studying at Savannah Colege of Art and Design. This was photographed on 16mm reversal stock. Kinkle says that as a student, he didn’t learn story structure but instead was taught an impressionistic approach to filmmaking. The film focuses on a prostitute who is pursued by a ghostly figure in white face makeup. (There are some visual echoes of Herk Harvey’s classic Carnival of Souls, which may or may not be intentional.) In the commentary, Kinkle says that this was the first short for which he held an audition: previous shorts had been filled with friends and classmates. Kinkle also talks about how wondrous modern digital photography is, in terms of enabling the camera crew to have an instant preview of footage, to ensure exposure levels, etc, are adequate. - Trailer (1:43). - Image Gallery (28 images).  Disc Two contains the following: Disc Two contains the following:

- Jug Face - ‘Staring Into the Pit’ (24:28). Kinkle is interviewed by critic Jon Towlson, in a recording of an online video call. The pair talk about the origins of Jug Face and the casting of the film. Towlson asks Kinkle about the film’s script, and the manner in which it interweaves influences from backwoods horror films and folklore, with an approach that is ‘more empathetic to the backwoods characters’ than backwoods horror pictures such as Wrong Turn. Kinkle explains that the ‘reality’ depicted within the film has its origins in his youth, growing up in a rural community, and his status as a ‘huge fan of The Wicker Man’. The story evolved from Kinkle’s realisation that ‘my life wasn’t my own anymore’ following the birth of his daughter: he had to ‘kill part of myself for the greater good’, especially when his wife went to work and he was left at home with the baby, and this experience worked its way into the story. - ‘Back Into the Woods’ (33:53). In another online video call, actress Lauren Ashley Carter speaks with Robert Nevitt, founder of Sheffield’s Celluloid Screams festival, about her experiences making Jug Face, including her interactions with the other performers in the picture. - ‘A Face Jug Tour’ (14:25). Kinkle takes the viewer on a tour of the face jugs in his office, and tells us of the origins of the face jugs and their association with families of the North Georgia area – which is where Kinkle encountered the practice of making face jugs. This is a weirdly fascinating little featurette. - Trailer (2:02).

Overall

These two features by Kinkle are a fascinating antidote to Hollywood’s current wave of horror pictures. With a strong sense of the rural space, and communities, Kinkle demonstrates a complexity in his approach to this material – eschewing the easy supernatural scares of most Hollywood horror pictures, or the condescending rationalism that other filmmakers may have brough to this material, in favour of something which is more subtle, more ambiguous, and therefore more unsettling. These two features by Kinkle are a fascinating antidote to Hollywood’s current wave of horror pictures. With a strong sense of the rural space, and communities, Kinkle demonstrates a complexity in his approach to this material – eschewing the easy supernatural scares of most Hollywood horror pictures, or the condescending rationalism that other filmmakers may have brough to this material, in favour of something which is more subtle, more ambiguous, and therefore more unsettling.

Both Jug Face and Dementer are impressive independent horror films. Arrow’s Blu-ray release contains excellent presentations of Kinkle’s two features, alongside some superb contextual material. Full-sized screengrabs. Please click to enlarge. Dementer

Jug Face

|

|||||

|