|

|

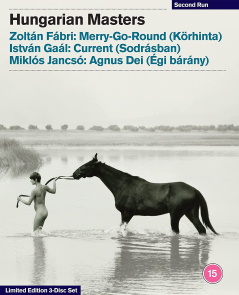

Hungarian Masters: Three films by Zoltán Fábri, István Gaál and Miklós Jancsó

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Second Run Review written by and copyright: Eric Cotenas (10th January 2022). |

|

The Film

Second Run presents a selection of essential works by three of Hungarian cinema's most renowned filmmakers. This special limited edition box set contains these celebrated films from stunning new 4K restorations and are being released for the first time ever on Blu-ray. Palme d'Or: Zoltán Fábri (nominee) - Cannes Film Festival, 1966 Merry-Go-Round (Körhinta): Having spent most of her young life with her family participating in a farming co-op, the youthful reverie of Marie Pataki (Electra, My Love's Mari Töröcsik) is shattered when her father István (Young Noszty and Mary Toth's Béla Barsi) decides that he is not seeing enough returns and decides to leave the commune, taking after boastful neighbor Sándor (In Soldier's Uniform's Ádám Szirtes). He not only forbids Marie associating with the co-op farmers – including love interest Máté Bíró (Goose Boy's Imre Soós) – but also has also agreed to marry her off to the middle-aged Sándor without her consent. Although resentful of her father's plans, Marie is advised by her mother (The Lady from Constantinople's Manyi Kiss) that "smooth talkers and jokers are bad farmers." Marie is reluctant to defy her father but Máté's fervent wooing of her – as well as having to be part of the wedding party of a family friend in which her own father declares "the bride is for sale" to announce the money dance in which men pay to dance with the bride before the vows – leads to a confrontation between authoritarian father and a once devoted daughter in which neither will back down. It may be 1953, but in rural Hungary, it is still the maxim that "land marries into land," at least among those who have land or want to own it. The film presumably skirted communist censorship by underlining its youthful defiance of authoritarian figures by associating Máté with the co-op and the life to which István and Sándor aspire seems to reach back further than the days when her mother chose to be a farmer's wife for security to the medieval (her mother says "that's a woman's fate and so it will be forever"); indeed, the film makes effort not to entangle Máté's conflict with István over his demand to the co-op to return the land on which Máté is farming with his defiant courtship of Marie by way of having him not only the way Marie and her mother must peddle wares at the market while waiting for István's and Sándor's scheme to "bear fruit" but also having Máté call the co-op counsel out for their complacency and reluctance to innovate as he and his friends have been doing on their own. The film is rather slow in its setup and becomes even more dreary as it goes on until the climactic scene of the wedding dance when it is no longer Marie and Máté being spun around the merry-go-round as they were in the opening scene but it is now them spinning but the effect is dizzying to the inebriated wedding party and the audience. From that point on, the drama intensifies and it is only in the aftermath of near violence that sober heads prevail (just not in a conventional way). István threatens to kill his daughter if she ever disrupts his plans "again" and retorts to Sándor's threats to sue him if he does not control his daughter – who he describes dismissively as having "gone crazy" – with "You want me to help you into my daughter's bed," and suggests that it is he who is inadequate to control his fiancée. The film has a look inspired by Italian neorealism but a narrative that is almost but not quite Old Hollywood. Director Zoltán Fábri (Professor Hannibal) started out as a production designer and his visual sense is apparent without the film looking overly storyboarded. Although the film was not well-received in its homeland initially, it was nominated for the Palme d'Or at Cannes and was twice voted by Hungarian critics as one of the twelve best Hungarian films in 1968 and 2000. Film Critics Award (Best Director): István Gaál (winner) and Best Cinematographer: Sándor Sára (winner) - Hungarian Film Critics Awards, 1965 Grand Prix (Best Film): Hunnia Filmstúdió (winner) - Karlovy Vary International Film Festival, 1964 Current (Sodrásban): Just before they are set to go off in separate directions, a group of school friends decide to spend a day at the beach. There's aspiring artist Luja (My Way Home's András Kozák), trainee botanist and poet Gabi (Túsztörténet's János Harkányi), physicist trainee Laci (Palm Sunday's Sándor Csikós), sports academy-bound Karesz (The Confrontation's Gyula Szersén), dropout shop boy Berci (The Last Adventure of Don Juan's Lajos Tóth), and future homemakers Anna (Silence and Cry's Andrea Drahota) and Böbe (Breakout's Marianna Moór), and Anna's new neighbor med student Zoltan (Red Psalm's Tibor Orbán). Zoltan (or Zoli) seems to have more in common with Böbe, making Anna and Karesz jealous; none of them, however notice the effect the flirting has on Gabi. The entire group goes for a swim in the river to dispel some of the tension, and a game of one-upmanship has each daring the other to drive deep for mud to sling at one another. It is only after they have gone back to shore to dry off and light a fire to cook that they realize that one of them is nowhere to be found. Gabi's clothes are still on the beach and there is no sign of him in the rushing water. Hoping that Gabi either hitched a ride on the fishing boat operated by a friend or that he might have gone home, the others attempt to investigate both possibilities on their own without letting Gabi's widow aunt (Green Years' Istvánné Zsipi) or their parents know. In the light of day, they are forced to share the conclusions of the police, their parents, and the rest of the town that Gabi's body will eventually surface in a few days. In the following days, the reflections of each on their respective relationships with Gabi and attempts to rationally absolve themselves of guilt bring forth recriminations and suppressed self-doubts. Seemingly taking a cue from Michelangelo Antonioni's L'avventura – with perhaps a touch of L'eclisse (the Italian New Wave having been as influential on Eastern European cinema as neorealism) – Current (Sodrásban) might perhaps be more accessible and relatable to viewers than the model films' more abstract alienation. The characters are all presented as on the cusp of professional adulthood, their affected maturity and intellectualism giving way to jokes and devolving into dares and displays of machismo – called out by one of the female characters who believes that Gabi was not as good a swimmer and that he was lovesick and deliberately provoked by the object of his affection – but childishly indecisive when there is an emergency. As they return to town hoping to find Gabi at home, they are already estranged from their home life as they peer through picture windows like a theater screen and notice more so than before that their oblivious parents are not as doing as Gabi's aunt. The ways in which each are affected by Gabi's disappearance run from the conventional to the abstract, with Luja explaining at length how he can no longer remember Gabi's face enough to draw or sculpt his likeness while also confessing his jealousy that Gabi was effortlessly better than him at art for which the other man hand no interest, while Zoltan similarly explains to Anna that he cannot have been expected to remember what Gabi looked like to notice he was missing having only just met him shortly before his disappearance. Current (Sodrásban) – the narrative feature film debut of documentarian István Gaál (Legato) – could be seen as a coming-of-age film in which the characters' are forced by circumstance into adulthood by way of estrangement by guilt and alienation from the comforts of home. Agnus Dei (Égi bárány) is set during the 133 days of the Hungarian Soviet Republic when the Hungarian Red Army were rooting out anti-communists in the countryside. The even-tempered canon (Private Vices, Public Virtues's Lajos Balázsovits) has been arrested while the while the Father Vargha (Beyond Time's József Madaras) is allowed to literally froth at the mouth in denouncing communists to the point of falling into seizures because the red army captain believes that arresting or killing the man will undermine them with his fervent local followers. When the Hungarian National Army troops show up, the decidedly non-pacifist Vargha takes up arms along with his flock and executes traitors as philanderers and "gives" their women to the faithful. Little do Varghas and his faithful realize that they are paving the way for an even more insidious form of fascism carried on the notes of a violin by a pleasant-looking young man (The Promised Land's Daniel Olbrychski) who initially plays the fool to Vargha's "White Terror" compatriots. Described by critic Tony Rayns as being set during the "confused dynamics" of 133 days, Agnus Dei (Égi bárány) is loosely scripted by director Miklós Jancsó and Gyula Hernádi (Adoption) in a manner that viewers lacking historical context will find confusing; however, as the directorial and cinematographic rhythms set in, the viewer will realize that no matter how characters exercise and abuse what power they have in the film, they are pawns not only of the filmmaker but of powers that allow a bit of leeway if only when applied to destructive ends. Vargha would be a raving madman if not propped up by bullies, and the conduct of his followers seems even more repulsive; for instance, the scene in which a farm girl recites the details of a medieval manual on torture to obtain confessions – which itself states that the victim will say anything the torturer wants to hear at a certain point – to the daughter of a communist (the torture is not carried out but the few women killed onscreen do seem to have more protracted deaths than the men who are executed by bullet to the back). With the camera of János Kende (Romanticism) panning, tracking, and zooming to the objectively surveil the action less as dramatic thrust than movement across space, Agnus Dei (Égi bárány) anticipates Jancsó's subsequent Red Psalm and Electra, My Love in their simultaneous choreography of camera and actors turning dramatic events into ritual performance. Here, it is only the fascist "pied piper" violinist who truly moves in rhythm with the camera (along with those who follow him blindly). It is difficult to sympathize with these easily-manipulated followers than to surmise that they deserve the government they get.

Video

Unreleased theatrically in the U.K. and not released stateside until 1958 by Trans-Lux, Merry-Go-Round (Körhinta) received a 4K restoration in 2017 when the Hungarian Film Institute became part of the Hungarian Film Fund. The 1080p24 MPEG-4 AVC 1.37:1 pillarboxed fullscreen transfer is virtually spotless even though it is a composite of different elements for some instances where frames were missing. The range of blacks, grays, and whites is appealing, and inconsistent sharpness is only an issue during the merry-go-round scene in which a heavy Debrie studio camera and its operator were mounted on one of the merry-go-round seats rather than a custom rig that one might expect from later films. Unreleased theatrically in the U.K. and not in the states until a repertory screening in 1998, Current (Sodrásban), the Hungarian Film Institute 4K restoration on Second Run's 1080p24 MPEG-4 AVC 1.85:1 widescreen Blu-ray is wonderfully unblemished and displays the sort of variegations of gray that one encounters in the Antonioni films of the same period that inspired it. This lends a slickness to the film that one does not expect to encounter in Hungarian film until later in the decade and less of a neorealist feel than encountered in Gaál's 1962 short Tisza - Autumn Sketches, a tone poem traveling along the same river environs in full color. One of the harder Jancsó films to see with no U.K. or U.S. theatrical or home video release, Agnus Dei (Égi bárány) comes to Blu-ray in a 1080p24 MPEG-4 AVC 1.66:1 widescreen presentation from a new 4K restoration by the Hungarian Film Institute. Shot almost entirely outdoors during the daytime, the film has a handsome look rich in browns, greens, and pinks of pastoral beauty that have been cleaned up to perfection without any digital artefacts and looking even handsomer than the earlier 2K restoration of Electra, My Love.

Audio

All three films have LPCM 2.0 mono tracks which are not particularly dynamic in keeping with productions of the time but they too have been meticulously cleaned – as per the restoration demo on Merry-Go-Round (Körhinta) – and the optional English subtitles are free of any errors.

Extras

Merry-Go-Round (Körhinta) features the most comprehensive extras in the package. In "We're Flying, Mari" (11:19), filmmaker István Szabó (Mephisto) relates the anecdote of how former French president François Mitterrand on the one hundredth anniversary of the first cineamtogaph screenings by the Lumičre brothers remarked that the essence of cinema was a girl on a merry-go-round but that he could not recall the film, which turned out to be Körhinta, and goes on to discuss Fábri's work as production designer and director and the strain of expressionism that was more evident in his other film. Also included are screen tests (19:08) which feature alternate line readings and inflections in different locations that might either be mocked up for the tests or scrapped in favor of the ones in the final film after Fábri saw them onscreen. The 2017 restoration demo (9:57) looks at the process of scanning the elements, seeking out missing frames from other materials, and the cleanup which does include efforts to correct and improve visual and audio limitations of the period unlike the Czech archival restorations which attempted to replicate the original theatrical experience (warts and all). The theatrical trailer (1:21) has also been included. Current (Sodrásban)'s extras start with an appreciation by author Gareth Evans (16:33) who was unaware of the film or the director until screened by Second Run, but he found it rich thematically (describing it in the set's accompanying booklet as one of "the most expressive films about youth at the time"), expounds on the multiple meanings of the title, and of the ways in which character and setting interact. The aforementioned 1962 short "Tisza - Autumn Sketches (Tisza - Őszi vázlatok)" (17:43) is also included, seeming as if it could be outtakes from scene establishing life along the river in the feature, as well as the film's theatrical trailer (2:26). The sole extra on Agnus Dei (Égi bárány) is an interview with director Miklós Jancsó (9:23) from 1987 in which the late director discusses his early career as a documentary cameraman which lead him to realize that the documentaries and newsreels of the Stalinist period were staged and not the way in which to judge the period, and that what was told was how they would have liked things to be while the co-op farmers in their Sunday best were really starving. He then goes onto discuss how he and others thought in the postwar period that they were creating a "new culture" but realizing that culture and art are bound by politics.

Packaging

Merry-Go-Round (Körhinta) includes a 20-page booklet with an essay by Hungarian cinema specialist John Cunningham who notes that the social realism was on the wane just two years after Stalin's death and that there was an "growing urge for change, in all aspects of Hungarian society" and cites among the film's inspirations István Szöts's People of the Mountains. Current (Sodrásban) includes a 20-page booklet with an essays by authors Peter Hames and Gareth Evans in which the former discusses the film's "dramatic use of landscape" and of music in light of Gaál's education as an art historian and musicologist, whiel the latter either expands on his video interview or vice versa in musing on the "absence of presence; the presence of absence" in his shorter piece. Agnus Dei (Égi bárány) includes a 16-page booklet with an essay by curator and critic Tony Rayns who draws parallels between Jancsó and Pier Paolo Pasolini, and between Agnus Dei and Salo.

Overall

In spite of possible western unfamiliarity with two of the filmmakers, Second Run's Hungarian Masters does deliver on its title and what the ad copy deems essential works of Hungarian cinema.

|

|||||

|