|

|

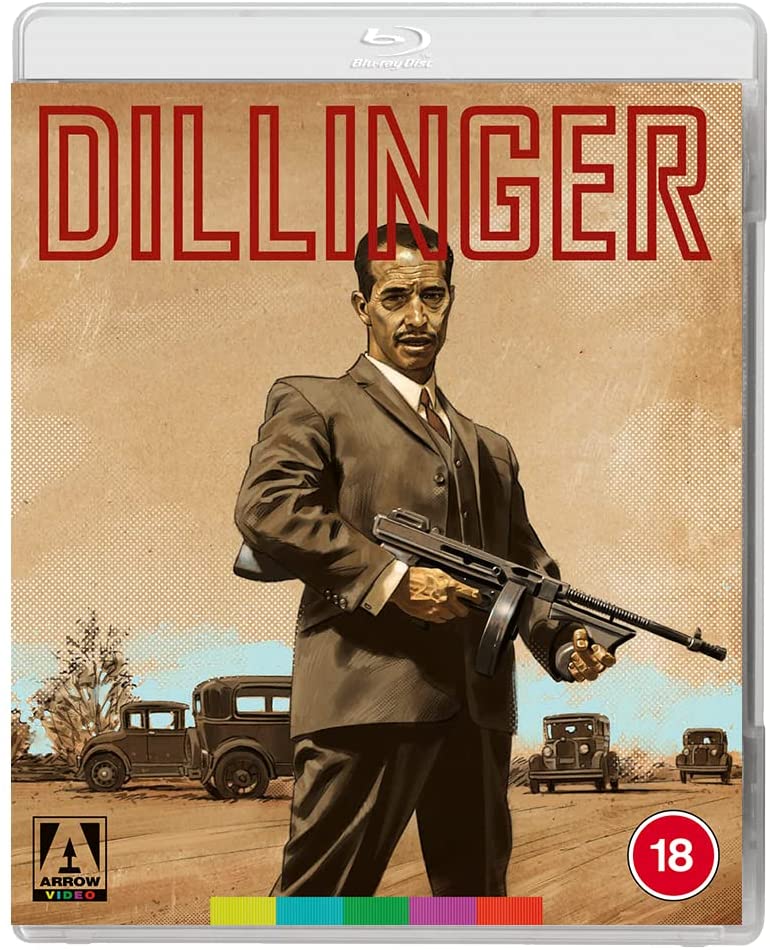

Dillinger (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (12th January 2022). |

|

The Film

Dillinger (John Milius, 1973) Dillinger (John Milius, 1973)

After the release of Arthur Penn’s Bonnie & Clyde (1969), which emblematised the New Hollywood’s bold new approach to filmmaking, maverick American filmmakers became fascinated with the era of Depression-era criminals. Subsequently a number of similar films appeared during the early 1970s. Chief among these was John Milius’ Dillinger (1973), an AIP production that differed from Penn’s groundbreaking picture in its refusal to romanticise the violent outlaws at the centre of its narrative. In fact, at one point in Dillinger, ‘Pretty Boy’ Floyd (Steve Kanaly) refers to Bonnie and Clyde as ‘a bunch of rabid dogs’, adding ‘I weren’t sorry to see them go’; to this, John Dillinger (Warren Oates) responds by asserting that when a ‘bunch of small timers get into it [robbing banks], they ruin it for everybody’. Motivated by the killing of several of his fellow ‘G-Men’ during the Kansas City massacre in 1933, Melvin Purvis (Ben Johnson) is tasked by J Edgar Hoover with bringing to justice a number of known criminals: ‘Pretty Boy’ Floyd (Steve Kanaly); ‘Machine Gun’ Kelly; ‘Baby Face’ Nelson (Richard Dreyfus); Wilbur Underhill; ‘Handsome Jack’ Klutas (Terry Leonard); and John Dillinger (Warren Oates). Dillinger and his gang, including Homer Van Meter (Harry Dean Stanton) and Harry Pierpoint (Geoffrey Lewis), have been tearing through Indiana, robbing banks. However, Dillinger has not committed a federal crime yet, though Purvis is desperate to peg him as having done so. Meanwhile, Dillinger becomes involved with young half-Native American, half-French woman Billie Frechette (The Mamas and the Papas’ Michelle Phillips), who his gang essentially abduct from her home on a reservation. As Dillinger and his group extend their violent activities, Purvis rounds on the gangsters on Hoover’s list, killing them one by one; eventually, the orbits of these two supremely vain figures, who represent opposite sides of the law, collide.  In writing the script for John Huston’s The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean (1972), a biopic of the legendary justice of the peace in Val Verde, Texas who declared himself ‘The Only Law West of Pecos’, Huston had deliberately intermingled the vague details of Bean’s life with legend. Milius’ script for that picture began with a preface which asserted that ‘If this story is not the way it was, then it’s the way it should have been’. His fast and loose approach to the historical facts in the Judge Roy Bean script, and its preface’s acknowledgement of the relationship between myth and reality in the context of any narrative based on historical events, is very much shared by Milius’ dramatisation of the story of John Dillinger. Though Dillinger has an aesthetic that is dominated by realism (heavy depth of field in the photography; documentary-style camerawork; the use of newsreel footage, montage, and voiceover), its narrative conflates events and characters, changing locations and the timeline of events. In writing the script for John Huston’s The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean (1972), a biopic of the legendary justice of the peace in Val Verde, Texas who declared himself ‘The Only Law West of Pecos’, Huston had deliberately intermingled the vague details of Bean’s life with legend. Milius’ script for that picture began with a preface which asserted that ‘If this story is not the way it was, then it’s the way it should have been’. His fast and loose approach to the historical facts in the Judge Roy Bean script, and its preface’s acknowledgement of the relationship between myth and reality in the context of any narrative based on historical events, is very much shared by Milius’ dramatisation of the story of John Dillinger. Though Dillinger has an aesthetic that is dominated by realism (heavy depth of field in the photography; documentary-style camerawork; the use of newsreel footage, montage, and voiceover), its narrative conflates events and characters, changing locations and the timeline of events.

Originally, Milius intended to direct The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean himself, with Warren Oates in the title role, on a low budget and possibly overseas; however, the script eventually landed, via Lee Marvin, in the hands of Paul Newman, who became fascinated with the prospect of playing Bean. Aware of Milius’s work owing to stories about the writer’s contributions to Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry (1971) and Sydney Pollack’s Jeremiah Johnson (1972), Newman facilitated the purchase of Milius’ script, for what was at the time a record sum of $300,000. (Milius’ typical fee, during that period, was less than $100,000.) However, though he parted with the script for Judge Roy Bean, the astronomical fee presumably being too tempting to refuse, Milius had never intended to sell it. He was ultimately dissatisfied with the resultant film, thinking that Newman was too handsome for the role, and Huston’s approach to directing the picture was too ‘Beverly Hills’. Following the sale of the script for The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean, Milius’ attention turned towards John Dillinger, another historical figure. In retrospect, it’s difficult not to see Milius’ Dillinger, with Warren Oates in its title role, as an attempt at capturing some of the spirit of Milius’ vision for The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean.  AIP managed to raise a budget of $1 million for Dillinger’s production, with approximately $150,000 of that going towards securing Warren Oates and Ben Johnson in the lead roles of, respectively, John Dillinger and G-Man Melvin Purvis. The film was shot in Oklahoma, where the production found it easiest to replicate the texture of Depression-era America, in terms of its rural and urban architecture. One may speculate that a significant portion of the budget was also invested in acquiring the splendid range of hats we see in the film: from the faded caps and grubby Western-style hats and fedoras of the rural folk, to the swankily expensive silverbelly Stetson that Homer wears in the film’s early sequences; from Purvis’ range of Homburgs in different colours, to the straw boaters that Dillinger’s gang wear when they rob banks (denoting them as gentlemen of leisure, enabling them to stand out from the poverty of their Dust Bowl surroundings). AIP managed to raise a budget of $1 million for Dillinger’s production, with approximately $150,000 of that going towards securing Warren Oates and Ben Johnson in the lead roles of, respectively, John Dillinger and G-Man Melvin Purvis. The film was shot in Oklahoma, where the production found it easiest to replicate the texture of Depression-era America, in terms of its rural and urban architecture. One may speculate that a significant portion of the budget was also invested in acquiring the splendid range of hats we see in the film: from the faded caps and grubby Western-style hats and fedoras of the rural folk, to the swankily expensive silverbelly Stetson that Homer wears in the film’s early sequences; from Purvis’ range of Homburgs in different colours, to the straw boaters that Dillinger’s gang wear when they rob banks (denoting them as gentlemen of leisure, enabling them to stand out from the poverty of their Dust Bowl surroundings).

Though much of Dillinger follows, well, John Dillinger, the film’s guiding point-of-view is arguably that of Melvin Purvis, the G-Man tasked by J Edgar Hoover with bringing Dillinger, and other public enemies, to justice. (The actions of the real Purvis, morally questionable though they sometimes were and equally inaccurate in their telling, led to a level of celebrity that caused Hoover to become jealous of his underling.) Purvis, played superbly by Ben Johnson, guides the film’s narrative via voiceover narration that appears at various points in the story, often accompanying a newsreel-like montage of monochrome still photographs (both authentic and staged), screaming newspaper headlines, and black-and-white footage. (Some of this footage was shot specifically for Milius’ film; other footage is culled from newsreels and 1930s/1940s-era Hollywood gangster movies.) This mixed-media approach, combined with a strong emphasis on photographic realism, suggests Milius may have been influenced by Francesco Rosi’s ‘cine-inchieste’: a hybrid of documentary and fiction that is often most closely associated with Rosi’s Salvatore Giuliano (1962), another biopic of an outlaw figure. The overall effect of this approach is not dissimilar to that of the mixing of material in Oliver Stone’s much later JFK (1991) and Natural Born Killers (1994).  As both a writer and director, Milius’ work during the 1970s and 1980s was sometimes decried by the likes of Pauline Kael as reactionary, and obsessed with ‘fascistic’ violence. Similar criticisms were often levelled against Sam Peckinpah, and Milius’ cinema shares a number of similarities, especially in terms of its depiction of violence, with Peckinpah’s work. (This is alongside the fact that a number of actors – including Oates, Johnson, and Harry Dean Stanton – often associated with Peckinpah’s work appearing in Dillinger.) Peckinpah once stated, in discussing violence in his films, that violence is ‘ugly, brutalising, and bloody fucking awful [….] And yet there’s a certain response that you get from it, an excitement because we’re all violent people’. Peckinpah’s depiction of violence was always tinged with that ambivalence: an awareness of the destructive, harmful, ‘bloody fucking awful’ potential of human savagery, wrapped in an understanding of the social urges that facilitate – nay, encourage and reward – violence and cruelty in all its forms. Milius’ cinema has a similar quality – which, as with Peckinpah’s work, some have denounced as a fascistic celebration of violence; such criticism frequently refuses to engage with the levels of irony Milius builds into his work. Here, in Dillinger, we see the staging of some of the most impressive scenes of violence and action to grace an American film: these are simultaneously exhilarating and terrifying, particularly as the Dillinger gang become increasingly militaristic in their heists following the recruitment of Pretty Boy Floyd and Baby Face Nelson. (After this, the gang graduate from using Tommy guns to wielding more intimidating BARs.) Milius uses careful edits to make the violence feel more impactful for the audience, squibs and moles encouraging the viewer to feel every bullet hit when principal characters buy the farm. As both a writer and director, Milius’ work during the 1970s and 1980s was sometimes decried by the likes of Pauline Kael as reactionary, and obsessed with ‘fascistic’ violence. Similar criticisms were often levelled against Sam Peckinpah, and Milius’ cinema shares a number of similarities, especially in terms of its depiction of violence, with Peckinpah’s work. (This is alongside the fact that a number of actors – including Oates, Johnson, and Harry Dean Stanton – often associated with Peckinpah’s work appearing in Dillinger.) Peckinpah once stated, in discussing violence in his films, that violence is ‘ugly, brutalising, and bloody fucking awful [….] And yet there’s a certain response that you get from it, an excitement because we’re all violent people’. Peckinpah’s depiction of violence was always tinged with that ambivalence: an awareness of the destructive, harmful, ‘bloody fucking awful’ potential of human savagery, wrapped in an understanding of the social urges that facilitate – nay, encourage and reward – violence and cruelty in all its forms. Milius’ cinema has a similar quality – which, as with Peckinpah’s work, some have denounced as a fascistic celebration of violence; such criticism frequently refuses to engage with the levels of irony Milius builds into his work. Here, in Dillinger, we see the staging of some of the most impressive scenes of violence and action to grace an American film: these are simultaneously exhilarating and terrifying, particularly as the Dillinger gang become increasingly militaristic in their heists following the recruitment of Pretty Boy Floyd and Baby Face Nelson. (After this, the gang graduate from using Tommy guns to wielding more intimidating BARs.) Milius uses careful edits to make the violence feel more impactful for the audience, squibs and moles encouraging the viewer to feel every bullet hit when principal characters buy the farm.

There is nevertheless an equivalence that is drawn between the brutality of the gangsters and the equally cruel violence of Purvis and the other G-Men. The scenes in which Purvis corners and kills the gangsters involved, however peripherally, in the Kansas City massacre are disturbing in their violence, with the G-Man displaying an absence of empathy. ‘I knew I’d never take him alive; I didn’t try too hard, neither’, Purvis narrates over his execution of ‘Handsome Jack’ Klutas. Worse still is the moment in which a badly wounded Homer is cornered by a group of townsfolk; politely asking for a doctor (‘Will you get a doctor, please?’) whilst laying on the floor, the unarmed Homer finds a response to his request in the form of a barrage of gunshots – an extreme sense of overkill to rival the murder of Officer Murphy (Peter Weller) in Paul Verhoeven’s much later RoboCop (1987) – fired by the crowd at Homer’s body. The sense of corruption within the law is amplified by the desperation with which Purvis seeks to pin a federal warrant on Dillinger; eventually, despite the gangster’s staging of numerous bank robberies, Purvis’ federal pursuit of Dillinger is given legitimacy when Dillinger drives a stolen car across state lines. The absurdity of this points to the absurdities of bureaucracy and the law, and the manner in which justice is bound with revenge. ‘Shoot Dillinger, and we’ll find a way to make it legal’, Purvis tells an underling at one point in the narrative. There is nevertheless an equivalence that is drawn between the brutality of the gangsters and the equally cruel violence of Purvis and the other G-Men. The scenes in which Purvis corners and kills the gangsters involved, however peripherally, in the Kansas City massacre are disturbing in their violence, with the G-Man displaying an absence of empathy. ‘I knew I’d never take him alive; I didn’t try too hard, neither’, Purvis narrates over his execution of ‘Handsome Jack’ Klutas. Worse still is the moment in which a badly wounded Homer is cornered by a group of townsfolk; politely asking for a doctor (‘Will you get a doctor, please?’) whilst laying on the floor, the unarmed Homer finds a response to his request in the form of a barrage of gunshots – an extreme sense of overkill to rival the murder of Officer Murphy (Peter Weller) in Paul Verhoeven’s much later RoboCop (1987) – fired by the crowd at Homer’s body. The sense of corruption within the law is amplified by the desperation with which Purvis seeks to pin a federal warrant on Dillinger; eventually, despite the gangster’s staging of numerous bank robberies, Purvis’ federal pursuit of Dillinger is given legitimacy when Dillinger drives a stolen car across state lines. The absurdity of this points to the absurdities of bureaucracy and the law, and the manner in which justice is bound with revenge. ‘Shoot Dillinger, and we’ll find a way to make it legal’, Purvis tells an underling at one point in the narrative.

Elsewhere, also like Peckinpah, Milius shows children as passive witnesses of violence and criminality. When Dillinger is arrested and transported to Lake County Jail (from which he escapes by fashioning a convincing pistol from a bar of soap, painting it black with boot polish), Milius shows amongst the crowd groups of children watching the gangster with glee. The viewer may be reminded of the manner in which Peckinpah frames children as witnesses (and, later, re-enactors) of the Starbuck massacre in the opening sequence of The Wild Bunch (1969), in particular. The gravitational pull of violence and criminality draws the young and impressionable into its orbit. Shortly afterwards, Purvis witnesses two young boys playing. He asks what game they are playing. ‘Cops and robbers’, the boys tell Purvis. ‘Crime doesn’t pay’, Purvis reminds them, ‘I bet your dad told you that’. Purvis gives the young boys a short spiel about growing up to work as a lawman. ‘I ain’t got no dad’, one of the boys replies, non-plussed, before walking away.  In its opening scene and in a few other places in the narrative, Dillinger also makes bold use of direct address. The film’s opening moments are presented from the point-of-view of a young, female bank teller in Indiana, 1933. An older female customer chastises the teller, before turning around to see Dillinger, wearing his straw boater, standing behind her. He smiles, and she asks what he is smiling at. ‘Whenever I see money, I gotta smile that way’, he tells the woman before approaching the counter, speaking to the camera directly and informing the teller that he and his gang are robbing the bank. ‘Nobody get nervous. You’ve got nothing to fear’, Dillinger – his speech measured, controlled – tells the customers gathered in the bank, ‘You’re being robbed by the John Dillinger gang. That’s the best there is. These few dollars you lose here today, they’re gonna buy you stories to tell your children and your great grandchildren’. Turning to the camera/teller, Dillinger adds sincerely, almost intimately: ‘This could be one of the big moments in your life. Don’t make it your last’. This moment of direct address is shocking, but it also highlights the screen charisma of Oates – and his casting as Dillinger is one of the best casting decisions of 1970s American cinema. In its opening scene and in a few other places in the narrative, Dillinger also makes bold use of direct address. The film’s opening moments are presented from the point-of-view of a young, female bank teller in Indiana, 1933. An older female customer chastises the teller, before turning around to see Dillinger, wearing his straw boater, standing behind her. He smiles, and she asks what he is smiling at. ‘Whenever I see money, I gotta smile that way’, he tells the woman before approaching the counter, speaking to the camera directly and informing the teller that he and his gang are robbing the bank. ‘Nobody get nervous. You’ve got nothing to fear’, Dillinger – his speech measured, controlled – tells the customers gathered in the bank, ‘You’re being robbed by the John Dillinger gang. That’s the best there is. These few dollars you lose here today, they’re gonna buy you stories to tell your children and your great grandchildren’. Turning to the camera/teller, Dillinger adds sincerely, almost intimately: ‘This could be one of the big moments in your life. Don’t make it your last’. This moment of direct address is shocking, but it also highlights the screen charisma of Oates – and his casting as Dillinger is one of the best casting decisions of 1970s American cinema.

This bold, remarkable opening sequence is followed by the film’s titles sequence: the credits play out in yellow font over a montage of monochrome Dorothea Lange/Walker Evans/FSA-style still photographs of Depression-era America. The stage is set: an era of poverty, foreclosures, and economic depression – against which the ostentatious qualities of the cinematic gangster, in pictures such as The Public Enemy (William A Wellman, 1931), made such figures aspirational for American cinema audiences in the 1930s. Certainly, as noted above, the costumes of Dillinger’s gang (Homer’s silverbelly Stetson, the boaters the gang wear when robbing banks, their tidy suits, and even their weaponry) denotes their wealth which is placed in sharp juxtaposition with the poverty that is evident in the towns whose banks they choose to rob. At one point, a vagrant sleeping outside the gang’s safe house makes an aside that implies he believes Dillinger’s group simply to be a cohort of wealthy, privileged, upper middle-class types rather than criminals; similar sentiments are expressed by other characters throughout the film. When Dillinger and his gang attend a village party, which features an extended group dance scene that pays homage to John Ford, the sheriff (‘Big’ Jim Wollard, played by Read Morgan) comments that ‘The combination of them fellers, standing over there, and them shiny cars, and them fancy-lookin’ girls, means they’s criminals’. When asked why this is so, Wollard adds simply that ‘Decent folk don’t live that good’.  Dillinger’s gang are no Robin Hoods, however. Early in the film, Milius takes care to show Homer shooting up the frontage of a gas station, after becoming frustrated following the failure of his attempts at intimidating the elderly attendant; Homer ends this encounter by jumping into the gang’s car, and saying ‘Step on it: I got his gumball machine’. The group laugh; their callousness demonstrates their lack of regard for those in poverty, which remains consistent throughout. (Later, Dillinger will comment dryly, whilst counting a bundle of stolen cash, ‘Depression! I ain’t never heard of it’.) Dillinger’s gang are no Robin Hoods, however. Early in the film, Milius takes care to show Homer shooting up the frontage of a gas station, after becoming frustrated following the failure of his attempts at intimidating the elderly attendant; Homer ends this encounter by jumping into the gang’s car, and saying ‘Step on it: I got his gumball machine’. The group laugh; their callousness demonstrates their lack of regard for those in poverty, which remains consistent throughout. (Later, Dillinger will comment dryly, whilst counting a bundle of stolen cash, ‘Depression! I ain’t never heard of it’.)

Nevertheless, Milius stops the narrative for a brief rural idyll, when after breaking out of Lake County Jail, Dillinger returns to his family home and visits his elderly dad, his sister, and a group of other relatives. As an instrumental, wistful version of the hymn ‘Give Me Joy in My Heart’ plays on the soundtrack, Dillinger is told by his father that ‘I never thought well of what you done [….] But times being what they are, and all these people think so highly of you: welcome home, son’. The hospitality, and integrity of rural, proletarian life is presented as a positive alternative to both the deception and cruelty of the law, and the vanity and self-interest of criminal. Later, as the film builds towards its climax, Dillinger returns to this location in a scene that pays homage to John Ford’s The Searchers (1956). Dillinger parks the stolen car he has been driving on the road nearby, and gets out to look at his family’s farmhouse. His dad and sister exit the building; as Dillinger’s sister runs to greet her older brother, Dillinger returns to the car and drives off – much as Ethan Edwards (John Wayne), aware that he can never reconcile the cruelty of his character with the utopianism of family life, turns away from his family and rides away at the end of Ford’s picture. Dillinger also has a fatal flaw of vanity. When he meets Billie Frechette in a bar, he is angered when he asks if she recognises him, and Billie suggests that he looks a little like Douglas Fairbanks. He is, of course, hoping that she will recognise him as being John Dillinger, bank robber. In fact, Dillinger is angered so much that he holds the patrons of the bar at gunpoint, robbing them, and telling them ‘I’m John Dillinger, and I don’t want you to ever forget’. (Dillinger and his gang essentially abduct Billie, and Dillinger’s initially cruel, violent treatment of Frechette eventually evolves into a mutual tenderness, with Billie willingly accompanying the gang and in fact aiding them: this sense of Billie’s development of ‘Stockholm Syndrome’ offers an eerie, oblique premonition of the Patty Hearst kidnapping, which would take place a year after the release of Dillinger.)  Following Dillinger, Milius scripted a television movie about Melvin Purvis, Melvin Purvis: G-Man (Dan Curtis, 1974), which places Purvis against Machine Gun Kelly. Despite early suggestions that Ben Johnson would return as Purvis, the part was eventually recast, with Dale Robertson playing the ‘G-Man’. Notable as AIP’s first foray into making television films, Melvin Purvis: G-Man was followed by another AIP-produced television movie about Purvis, The Kansas City Massacre (Dan Curtis, 1975). However, Milius had been deeply dissatisfied with his experience with AIP during the production of Melvin Purvis: G-Man: he would later speak derogatively about its director, Dan Curtis, and would state that the producers bowdlerised his script. This negative experience ensured that Milius didn’t return to write The Kansas City Massacre. Following Dillinger, Milius scripted a television movie about Melvin Purvis, Melvin Purvis: G-Man (Dan Curtis, 1974), which places Purvis against Machine Gun Kelly. Despite early suggestions that Ben Johnson would return as Purvis, the part was eventually recast, with Dale Robertson playing the ‘G-Man’. Notable as AIP’s first foray into making television films, Melvin Purvis: G-Man was followed by another AIP-produced television movie about Purvis, The Kansas City Massacre (Dan Curtis, 1975). However, Milius had been deeply dissatisfied with his experience with AIP during the production of Melvin Purvis: G-Man: he would later speak derogatively about its director, Dan Curtis, and would state that the producers bowdlerised his script. This negative experience ensured that Milius didn’t return to write The Kansas City Massacre.

Video

Running for 107:16 mins, Dillinger is presented on Arrow Video’s release in a 1080p presentation which uses the AVC codec. The film fills slightly over 32Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, and the presentation is in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. Running for 107:16 mins, Dillinger is presented on Arrow Video’s release in a 1080p presentation which uses the AVC codec. The film fills slightly over 32Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, and the presentation is in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1.

Though shot predominantly on 35mm colour stock, Dillinger also features some montages of monochrome stills and black and white film footage from various sources. The film’s photography fares very well on this HD presentation, which according to Arrow’s press materials is sourced from a new 2k restoration that is based on a scan of the interpositive. Dillinger was deliberately shot in a manner which privileged strong depth of field, and often using lenses of shorter focal lengths to achieve this. (Milius was convinced that this aesthetic bestowed a greater sense of photographic realism upon the subject matter, by simultaneously replicating how the human eye sees the world and the visual paradigms of photojournalism.) Low light scenes were shot on faster film stock, with mostly natural lighting, which results in a very heavy grain structure during these moments: again, this enhances the visual realism of the photography. Contrast levels are pleasing, with a balanced gradation from shoulder to toe of the exposure, and the muted colour palette sometimes looks a little ‘washed out’ (though this may be a creative choice, as all presentations of the film that this writer has seen have carried a similar appearance in this regard), and there is some minor damage here and there – most prominently some visible vertical scratches in the scene in which Dillinger thrashes Baby Face Nelson by the lake. That said, all of the damage is organic, and thanks to a robust encode which retains the structure of 35mm film within the presentation, this HD release of Dillinger is satisfyingly film-like. Some full-sized screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 track. This is clear and problem-free, demonstrating good range and fidelity. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included.

Extras

The disc includes the following extra features: The disc includes the following extra features:

Audio commentary with Stephen Prince. Stephen Prince offers an informative, well-research commentary track which offers both analysis and background information about the production, and about the historical events on which the film is based. Prince discusses Milius’ loose approach to the facts of the Dillinger case, and reflects on Milius’ incorporation into the film of various, sometimes surprising historical details. Prince argues that Milius doesn’t look towards Penn or Peckinpah, in terms of Dillinger’s approach to violence, but instead towards John Ford – who was one of Milius’ idols. It’s an excellent commentary track, and well worth a listen. - Music and Effects Track. - ‘Shooting Dillinger with Jules Brenner’ (12:03). The director of photography on Dillinger, Jules Brenner, reflects on his career and talks about his work on Dillinger. He suggests that his work on Dalton Trumbo’s Johnny Got His Gun (1971) was what led to him being offered Dillinger. Brenner discusses Milius and his approach to writing: Milius was gregarious and would pitch various projects at offices before retiring to his own office and writing ten pages of script at the end of the day. Milius ‘wasn’t particularly knowledgeable about the use of camera and lighting’, but would focus on the actors whilst Brenner concentrated on the technical aspects of shooting a scene. Brenner says that he prefers source lighting, ‘reproduc[ing] those effects’ of natural lighting in his photography. Many of the romantic scenes, Brenner says, were deliberately backlit (often by window light) in order to retain the ‘romantic tecture’ of the moment. Brenner also talks about his brief appearance in the film, as Wilbur Underhill, who is killed by Purvis and his men. ‘John’s direction to me was “Gurgle”’, Brenner says.

- ‘Lawrence Gordon: Original Gangster’ (10:10). Gordon, who produced the film, talks about how he enticed Samuel Z Arkoff to finance the film, despite it being a ‘period piece’ and therefore requiring period costumes, cars, locations, and so on. Gordon approached Milius to work on the film, knowing that Milius wanted to transition from writing to directing. Ultimately, the film was one of the most expensive pictures produced by AIP. Gordon talks about casting of the film, and particularly the casting of Frank McRae as Reed Youngblood, after McRae approached Gordon on the lot. Gordon also praises Milius’ skill as a writer (and director), saying ‘His scripts are wonderful’. ‘Ballads and Bullets with Barry DeVorzon’ (12:02). Composer DeVorzon talks about the film’s score. DeVorzon discusses how he came to be a composer of film music, working initially with Stanley Kramer. When Gordon commissioned DeVorzon to score Dillinger, DeVorzon conducted research into music of the film’s period, using this as source music to establish the film’s temporal setting. DeVorzon says that he and Milius decided not to use music in the scenes of violence, which renders those scenes more impactful and realistic. DeVorzon compares Milius to Teddy Roosevelt, and says that the director ‘understod the rural environment’ in which much of the film takes place. Milius demanded ‘Red River Valley’ on the soundtrack when Dillinger returns home to his family; though DeVorzon thought this was too cliched, Milius stuck to his guns, arguing that ‘If it [‘Red River Valley’] is good enough for John Ford, it’s good enough for me’. - Gallery (100 images). - Trailer (2:29).

Overall

This writer’s first encounter with Dillinger was via a late-night television screening in the late-80s. It was a defining period in the life of a young cinephile, and the film stuck with me to such an extent that whilst my peers were singing the praises of other New Hollywood gangster films (Coppola’s The Godfather, in particular), Dillinger remained my favourite of such films – and in fact, one of my favourite American films of all time. Though I bought the German Blu-ray release of Dillinger when it was released, I was deeply jealous when Arrow elected to choose the film as one of their first releases in the US. That jealousy was warranted, because Arrow’s release of Dillinger – which has now been ported to the UK market – is superb. The HD presentation of the main feature is excellent, and the film is supported by some wonderful contextual material. This writer’s first encounter with Dillinger was via a late-night television screening in the late-80s. It was a defining period in the life of a young cinephile, and the film stuck with me to such an extent that whilst my peers were singing the praises of other New Hollywood gangster films (Coppola’s The Godfather, in particular), Dillinger remained my favourite of such films – and in fact, one of my favourite American films of all time. Though I bought the German Blu-ray release of Dillinger when it was released, I was deeply jealous when Arrow elected to choose the film as one of their first releases in the US. That jealousy was warranted, because Arrow’s release of Dillinger – which has now been ported to the UK market – is superb. The HD presentation of the main feature is excellent, and the film is supported by some wonderful contextual material.

Dillinger’s script is superb in its avoidance of verbosity, and riddled with black humour. Standout moments, in this regard, include Homer’s use of litotes as he is cornered and killed by the vengeful townsfolk. (‘Things ain’t working out for me’, he mutters as they round on him with various firearms.) Milius’ cinema is an existential cinema – not concerned with characters’ psychology but rather with their actions. There have been other tellings of the story of John Dillinger – from Max Nosseck’s 1945 Dillinger and its 1991 remake, directed by Rupert Wainwright, to Michael Mann’s Public Enemies (2009). None have the impact of Milius’ version, however – and the manner in which Milius fuses the story of Dillinger with the texture of a John Ford picture. Ultimately, Milius’ Dillinger is arguably one of the best US films of the 1970s, and Arrow’s Blu-ray release is pretty much definitive. Please click the screengrabs below to enlarge them.

|

|||||

|