|

|

The Film

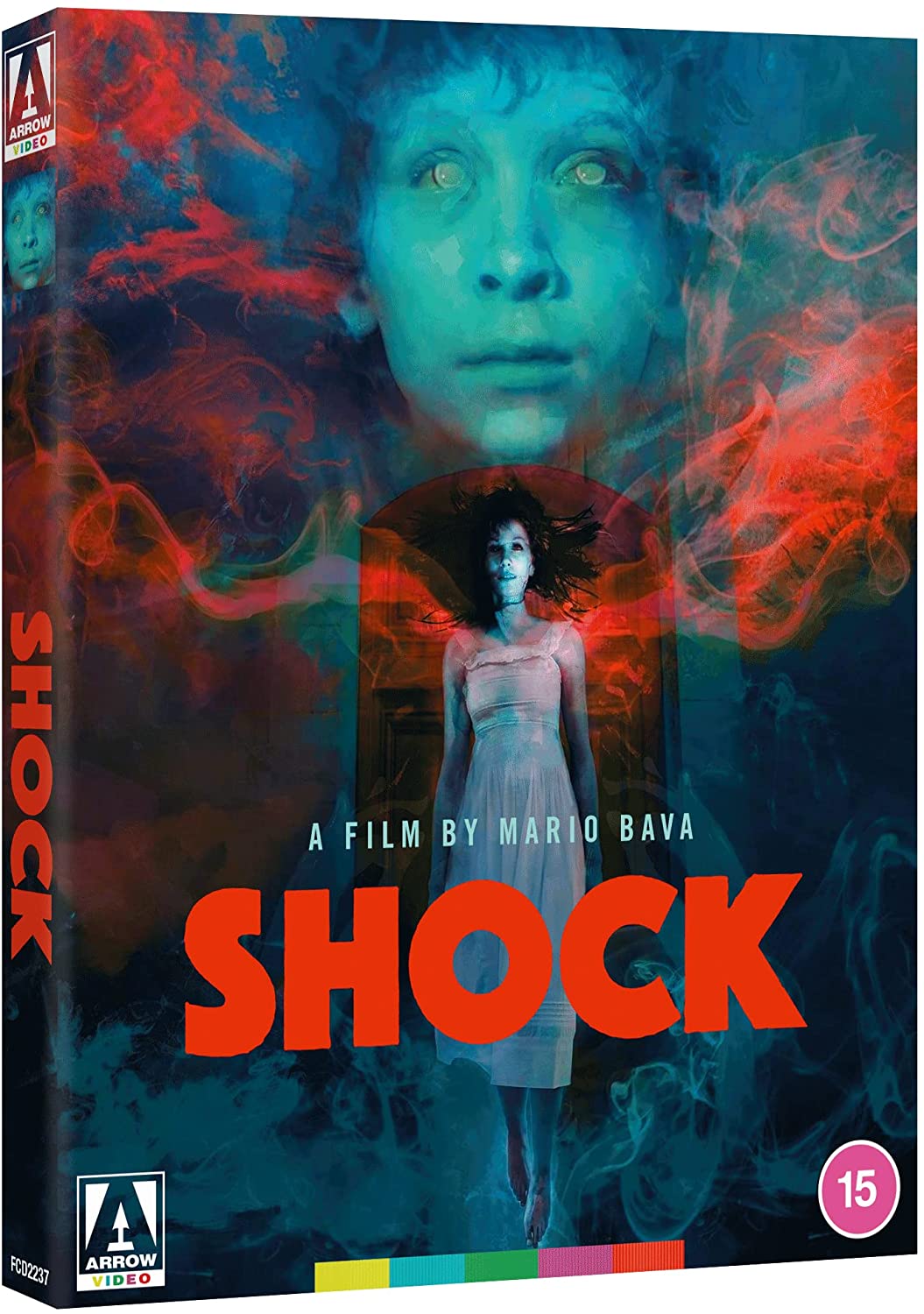

Shock (Mario Bava, 1977) Shock (Mario Bava, 1977)

Newly-married couple Dora (Daria Nicolodi) and Bruno (John Steiner), an airline pilot, move into a house in which Dora had previously lived with her first husband. Dora’s first husband apparently vanished at sea, presumably committing suicide; after this, Dora spent a period of time in a psychiatric hospital whilst also kicking a junk habit. Dora and Bruno are also in the company of Dora’s son Marco (David Colin, Jr.). Marco begins to act strangely, and whilst Bruno is away, Dora experiences various phenomena which may be interpreted as supernatural. However, is she simply imagining these events, or is there a conspiracy to drive her out of her mind? Mario Bava experienced some severe disappointments in the mid-1970s, including the re-editing of what is arguably his most personal film, Lisa e il diavolo (Lisa and the Devil, 1974), by its producer Alfredo Leone, into a vapid clone of The Exorcist; and the aborted production of Cani arrabiati (Rabid Dogs), after that film’s producer (Roberto Loyola) declared bankruptcy. Following his experiences on those two projects, Bava took a rest from filmmaking for a couple of years before returning in 1977 to direct Shock (aka Schock). Shock would be Bava’s last completed feature film; his only other credit, as a director, before his death in 1980 was an adaptation of Prosper Mérimée’s 1835 short story ‘Venus d'Ille’ for Italian television – though he did shoot some second unit work for Dario Argento’s Inferno (1980). Bava worked on both Shock and ‘La Venere d’Ille’ (the Mérimée adaptation, which was aired on Italian television in 1981, after Bava’s death) with his son Lamberto, and actress Daria Nicolodi. The two Bavas co-directed both films, though Lamberto Bava was not credited as co-director on release prints of Shock. According to the interview with Lamberto Bava that is included on this new release of Shock by Arrow Video, Mario Bava delegated his directing role to his son during scenes that required actors to deliver dialogue; in this sense, the working relationship between father and son seems to parallel that of, say, Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg during the making of Performance (1970) – with one taking charge of more technical aspects of the direction of the film, including the lighting and photography, and the other directing the actors in their performances.  There has been some suggestion that the script for Shock was inspired by Hilary Waugh’s 1971 novel The Shadow Guest. However, in truth the narrative is such a generic ghost story, combining elements of the Bluebeard myth, Du Maurier’s Rebecca, Dorothy Macardle’s 1941 novel Uneasy Freehold (adapted by Lewis Allen in 1944 as The Uninvited), and perhaps a hint of Patrick Hamilton’s 1938 play Gas Light – along with undoubted touches of then-popular US haunted house films like Dan Curtis’ 1976 adaptation of Robert Marasco’s novel Burnt Offerings, and its ensuant clones – that trying to identify such specific sources of narrative inspiration seems relatively futile. That said, there are certainly some similarities with the Waugh novel – most particularly the focus on a woman who is compelled to remain in a seemingly haunted house (in the novel, on the English coast), to which she moves with her husband following a nervous breakdown. There has been some suggestion that the script for Shock was inspired by Hilary Waugh’s 1971 novel The Shadow Guest. However, in truth the narrative is such a generic ghost story, combining elements of the Bluebeard myth, Du Maurier’s Rebecca, Dorothy Macardle’s 1941 novel Uneasy Freehold (adapted by Lewis Allen in 1944 as The Uninvited), and perhaps a hint of Patrick Hamilton’s 1938 play Gas Light – along with undoubted touches of then-popular US haunted house films like Dan Curtis’ 1976 adaptation of Robert Marasco’s novel Burnt Offerings, and its ensuant clones – that trying to identify such specific sources of narrative inspiration seems relatively futile. That said, there are certainly some similarities with the Waugh novel – most particularly the focus on a woman who is compelled to remain in a seemingly haunted house (in the novel, on the English coast), to which she moves with her husband following a nervous breakdown.

On a first viewing, throughout much of the film, the viewer may wonder whether Dora’s experiences of unexplained phenomena are to be taken as a de facto truth, or whether events are being staged by Bruno in some sort of Gas Light-like conspiracy to drive Dora insane. Certainly, the gradual revelation of Dora’s past – as a junkie, who experienced a mental collapse following the disappearance of her first husband, before kicking the habit and being rehabilitated with the help of a psychiatrist (Ivan Rassimov) – suggests that her point of view, which the film steadfastly follows throughout most of its running time, may be unreliable. Bruno’s absences from the family home, apparently enforced by his job as an airline pilot, seem to cast suspicion upon him; and what exactly is behind that un-plastered jerry-rigged wall in the basement? (Admittedly, the inference that Bruno may be ‘gaslighting’ his wife perhaps comes just as much from Steiner’s association with the roles that he played in films released after Shock – such as his performance in Tinto Brass’ Caligula, or Ruggero Deodato’s Inferno in diretta / Cut and Run).  Bava’s approach within this film is deeply humanistic: both Dora and Bruno are rounded characters, who act with human flaws but seem intended to try to ‘make things work’ despite Dora’s tragic, painful past. Making a convincing screen couple, Steiner and Nicolodi play their characters enigmatically, certainly, but also deeply sympathetically. Bruno seems to care quite genuinely for his stepson, Marco, and acts playfully with him – whilst Dora adopts a distanced parenting style, for the most part leaving Marco alone in his room to colour or play with his toys. When this writer first saw Shock, as a child during the 1980s, my way into the film was through Marco, the young witness to the horrors that take place in the villa. The actions of Dora, and particularly Bruno, seemed enigmatic: why would these adults choose to raise a child in such a disturbing environment? Revisiting this film as an adult in my forties, with children of my own, Dora’s ‘hands off’ parenting style feels deeply detached – neglectful, even. Bava’s approach within this film is deeply humanistic: both Dora and Bruno are rounded characters, who act with human flaws but seem intended to try to ‘make things work’ despite Dora’s tragic, painful past. Making a convincing screen couple, Steiner and Nicolodi play their characters enigmatically, certainly, but also deeply sympathetically. Bruno seems to care quite genuinely for his stepson, Marco, and acts playfully with him – whilst Dora adopts a distanced parenting style, for the most part leaving Marco alone in his room to colour or play with his toys. When this writer first saw Shock, as a child during the 1980s, my way into the film was through Marco, the young witness to the horrors that take place in the villa. The actions of Dora, and particularly Bruno, seemed enigmatic: why would these adults choose to raise a child in such a disturbing environment? Revisiting this film as an adult in my forties, with children of my own, Dora’s ‘hands off’ parenting style feels deeply detached – neglectful, even.

Thematically, Shock has much in common with Mario Bava’s earlier film La frustra e il corpo (The Whip and the Flesh, 1963). Both films focus on women who struggle to overcome romantic relationships with abusive men, and who experience events that may or may not be supernatural – leading in both instances to an unravelling of their relationships with other family members. In Shock, the various moments of ‘supernatural’ phenomena – Marco’s tiny hand turning into decomposing claw which grabs at Dora’s neck, or the rotting corpse’s hand that Dora imagines reaching out of the ground to grab her wounded ankle when she trips on a garden rake – are carried by the use of various photographic techniques. In particular, Bava makes use of a lens filter (a distorted piece of glass) which makes the scene bubble and distort, as if it is being viewed under water. These moments could equally be moments of ghostly goings-on, or Dora’s delusions; either way, they represent the raw wound of Dora’s past, which oozes into the present. We also have an articulation of the Freudian primal scene, when Marco – who at times seems to become ‘possessed’ by whatever resides in the house – is shown lying in bed, Bava crosscutting between this and a moment depicting Dora and Bruno, both nude, making love on the sofa. The implication is that something supernatural is watching them, and that this vision is being communicated psychically to Marco. (It becomes obvious, fairly quickly, that this ‘entity’ – whether it is ‘real’ or simply a product of Dora’s imagination – is a representation of Dora’s first husband, Marco’s father.) The ambiguity with which the film depicts the ‘supernatural’ has precedent in Bava’s work, notably, in the director’s preferred cut of Lisa and the Devil.  As Stephen Thrower suggests in the special features on this disc, there is a loose lineage between the ‘daylit horrors’, with modern day settings, established in the one-two punch of Polanski’s Rosemary Baby and Romero’s Night of the Living Dead in 1968, and the likes of Shock during the 1970s. With its sequences suggestion Marco may be possessed by the ghost of his father (including a moment – equally bizarre and unsettling – in which the boy falls on top of his mother and writhes whilst making grunting noises, in clear mimicry of the sex act), Shock also looks sideways towards the popularity of Exorcist-inspired films about demonic possession, such as Un urlo dalle tenebre (Cries & Shadows/Naked Exorcism, 1975). In the US, the film was released as Beyond the Door II, the retitling capitalising on Ovidio G Assonitis’ 1974 demonic possession picture Chi sei? (released as Beyond the Door in English-speaking countries). Shock, itself, established a tone for Italian haunted house movies that would be extended in the 1980s, in films such as Umberto Lenzi’s Ghosthouse (1988), Lamberto Bava’s La casa dell’orco (The Ogre, 1989), and their cinematic brethren. As Stephen Thrower suggests in the special features on this disc, there is a loose lineage between the ‘daylit horrors’, with modern day settings, established in the one-two punch of Polanski’s Rosemary Baby and Romero’s Night of the Living Dead in 1968, and the likes of Shock during the 1970s. With its sequences suggestion Marco may be possessed by the ghost of his father (including a moment – equally bizarre and unsettling – in which the boy falls on top of his mother and writhes whilst making grunting noises, in clear mimicry of the sex act), Shock also looks sideways towards the popularity of Exorcist-inspired films about demonic possession, such as Un urlo dalle tenebre (Cries & Shadows/Naked Exorcism, 1975). In the US, the film was released as Beyond the Door II, the retitling capitalising on Ovidio G Assonitis’ 1974 demonic possession picture Chi sei? (released as Beyond the Door in English-speaking countries). Shock, itself, established a tone for Italian haunted house movies that would be extended in the 1980s, in films such as Umberto Lenzi’s Ghosthouse (1988), Lamberto Bava’s La casa dell’orco (The Ogre, 1989), and their cinematic brethren.

In 1980s Britain, the Stablecane VHS release of Shock seemed ubiquitous on market stalls and in video shops. With its minimalist cover (a white background, with the film’s title written in crimson blood, a small anguished face within the ‘o’ of the word ‘Shock’), alongside the same company’s releases of Dario Argento’s The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970) and Riccardo Freda’s The Horrible Dr Hichcock (1962). The Stablecane release omitted the scene in which Marco lies on top of Dora, making strange noises and pulling faces, and the ensuant scene in which Marco and Dora watch a puppet show in the park. It also cuts the scene in which Marco climbs in bed with his mother and touches her throat as she sleeps, the child’s hand transforming into the decayed forearm of his father’s ‘ghost’. There were also some brief trims to the sequence in which Dora feverishly writhes in her bedsheets, including a moment in which she gruesomely crushes a fake hand from which blood gushes onto the blankets.

Video

Arrow Video have released Shock on Blu-ray, with a presentation that is based on a new 2k restoration sourced from the film’s original negative. This 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec, and is in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The film is uncut, with a running time of 92:31 mins. Arrow Video have released Shock on Blu-ray, with a presentation that is based on a new 2k restoration sourced from the film’s original negative. This 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec, and is in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The film is uncut, with a running time of 92:31 mins.

Shot on 35mm colour stock, Shock has a presentation on this disc that is, on the whole, excellent. From the disc main menu, the viewer is presented with the option of watching the film in either its Italian or English version. This choice determines the language of the onscreen titles and text within the film, along with its audio track (either spoken English, with optional English subtitles; or spoken Italian, with optional English subtitles). The level of detail throughout is very impressive, and the encode to disc is solid – ensuring the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film. Colours are consistent, and skintones natural: this is a film with a predominantly naturalistic colour palette, with strong use of brown, orange, and red hues; and this is captured superbly here. Contrast levels are also very pleasing: there are some moments in which density fluctuations are evident in the shadows, but predominantly blacks are deep, rich, and velvety, with the curve from the middle of the exposure to the toe being subtly graduated; and the curve into the shoulder being equally nuanced. Highlights are protected. There is some organic film-related damage, including some vertical lines and stains. In all, this is a very impressive presentation of Shock, and is far superior to the film’s previous home video releases.

NB. There are some full-sized screengrabs taken from this disc at the bottom of this review. Please click these to enlarge them.

Audio

As noted above, the disc menu presents the viewer with the option of watching Shock in its English or Italian versions. Both English and Italian audio tracks are presented in DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0. Both tracks are rich and deep, with impressive range that showcases everything from the bassy riffs of main theme to the shrill screams of the actress dubbing Nicolodi. (Nicolodi was dubbed in both the English version and Italian version, because the film’s producer thought the actress’ voice was too ‘masculine’.) Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are provided for the English track, and optional English subtitles translating the Italian dialogue are provided for the Italian track. Both sets of subtitles are easy to read and free from issues.

Extras

The disc includes the following contextual material: The disc includes the following contextual material:

- An audio commentary with Tim Lucas. Tim Lucas offers a commentary on Shock that examines the film through the lens of its position in Mario Bava’s career (ie, as his final theatrical feature film). Lucas discusses the relationship between Bava and his son, Lamberto Bava; and he also considered the film’s relationship with the work of contemporaries within Italian genre filmmaking at the time, such as Dario Argento. It’s a typically encyclopedia commentary by Lucas, densely packed with factual detail (regarding topics such as the careers of the actors and key personnel). - ‘A Ghost in the House’ (30:34). This new interview with Lamberto Bava sees the filmmaker reflecting on Shock. Bava says that he read a story by Guy de Maupassant (‘La Horla’) during the 1960s, which inspired him to collaborate with Dardano Sacchetti and Franco Barberi on the writing of a three-page script (‘It’s Always Cold at 33 Clock Street’). This script focused on a woman who moved into a house where objects moved by themselves. Sachetti and Barberi asked Lamberto to share the script with his father, but other projects got in the way, until Mario Bava was asked to work on a film written by another writer – into which Lamberto Bava worked elements of the script on which he had collaborated with Sachetti and Barberi. Bava also talks about the casting of both John Steiner and Daria Nicolodi, who he describes as a ‘formidable actress’; and he reflects on the filming of some of the special effects sequences. The exteriors for the film were shot in the villa of Enrico Maria Salerno, Bava reveals, and Dora’s first husband was played by Nicola Salerno, the son of Enrico Maria Salerno, in a role that is uncredited. Bava also points out the two uncredited cameo appearances he makes in the film, as one of the removal men, and later as a passenger in the airplane that experiences turbulence. Italian, with optional English subtitles.

- ‘Via Dell’Orologio 33’ (33:48). In this new interview, Dardano Sacchetti discusses his contribution to Shock. The script that became Shock was originally known as ‘It’s Always Cold at 33 Clock Street’, and then ‘The Housemaster’. Sacchetti talks about meeting Mario Bava after his very public disagreement with Dario Argento over the script for Il gatto a nove code (Cat O’Nine Tails). During that meeting, Sacchetti came up with the story for what would become Bava’s Ecologia del delitto (Bay of Blood). This was after Bava had made Danger: Diabolik (1968), which Sacchetti openly criticises here. Bava, with his well-documented dislike of actors, told Sacchetti that he wanted to make a film in which the central character was a house; Sacchetti rose to that challenge, devising a narrative in which a child ‘moves around a very ambiguous house’ – one which has a life and secrets of its own. Over a number of years, the project passed through the hands of various producers. Sacchetti was frozen out of the project, and apparently was only informed that the film was being made by Luigi Montefiore, who felt it unethical that Sacchetti had not been consulted about the fact that his script had entered production – and owing to legal proceedings surrounding the bankruptcy of the producer who had originally bought the script, Sacchetti would not be paid for it. Nevertheless, Sacchetti praises Mario Bava’s ‘classical’ approach to making the film, and the director’s use of the camera to communicate the supernatural: Sacchetti argues that ‘every single film [of Bava’s] is a lesson in the grammar of cinema’. Italian, with optional English subtitles. - ‘The Devil Pulls the Strings’ (20:45). Alexandra Heller-Nicholas narrates a video essay looking at Shock. Heller-Nicholas reflects on the huge Hand of Buddha that occupies space in the living room of Bruno and Dora – focusing on its prominence within the mise-en-scene of the film. For Heller-Nicholas, this hand has a key symbolic function within the narrative, which is connected to a theme of puppetry.

- ‘Shock! Horror!: The Stylistic Diversity of Mario Bava’ (51:46). Stephen Thrower offers an extended appreciation of Mario Bava’s body of work as a filmmaker. Thrower talks about his first experience of viewing Shock, on a double bill with Lucio Fulci’s The Beyond; and he says that whilst Shock is often suggested to be very different, stylistically, from Bava’s other pictures, this is ultimately a non-issue within the context of how diverse Bava’s body of work is. Thrower offers an analysis of Bava’s key films, which highlights just how diverse they are in terms of setting, narrative, and visual style. For Thrower, Bava’s Shock represents an approach to horror filmmaking that is an extension of the twin influences of Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby and Romero’s Night of the Living Dead in 1968 – which shifted horror away from Gothic paradigms to ‘daylit horror’ which placed a greater emphasis on psychological realism. - ‘The Most Atrocious Tortur(e)’ (4:12). Italian critic Alberto Farina talks about his interviews with Daria Nicolodi, who once showed Farina a drawing Bava had made for her, titled ‘The Most Atrocious Tortur [sic]’ – a title that Farina suggests was an allusion to the fact that Shock’s producer forced Bava to dub Nicolodi, because the producer believed Nicolodi’s voice was too ‘masculine’. This drawing contains a caricature of Nicolodi, together with the various objects that torment her character in the film. Italian, with optional English subtitles. - Trailers: Italian trailer (3:35); US ‘Beyond the Door II’ TV Spots – ‘Play All’ (1:51); TV Spot 1 (0:31); TV Spot 2 (0:27); TV Spot 3 (0:11); TV Spot 4 (0:11); US ‘Beyond the Door II’/‘The Dark’ TV Spot (0:31). - Image Galleries: Posters (7 images); Italian Fotobuste (12 images); Japanese Souvenir Program (11 images).

Overall

This writer first encountered Shock on VHS, via the aforementioned UK Stablecane release, before being fully aware of who Mario Bava was. (That knowledge would come later, via the BBC’s broadcast of La maschera del demonio / Mask of Satan and Bava’s cut of Lisa and the Devil in 1990 or thereabouts, and Redemption’s VHS releases of Bava’s films.) Shorn of any comparison with Bava’s other work, I always regarded Shock as a very well-made, supremely creepy haunted house film – its visual flourishes setting it apart from contemporaneous American ghost pictures. That said, it’s easy to see why cinephiles whose first viewing of this film took place within a frame of expectations set by Bava’s other pictures, have found Shock to be something of an anathema within its director’s body of work. However, as Stephen Thrower argues very clearly in the extra features of Arrow Video’s release, this sense of diversity (of theme and approach) is arguably a key characteristic of Bava’s cinema, when taken as a whole. This writer first encountered Shock on VHS, via the aforementioned UK Stablecane release, before being fully aware of who Mario Bava was. (That knowledge would come later, via the BBC’s broadcast of La maschera del demonio / Mask of Satan and Bava’s cut of Lisa and the Devil in 1990 or thereabouts, and Redemption’s VHS releases of Bava’s films.) Shorn of any comparison with Bava’s other work, I always regarded Shock as a very well-made, supremely creepy haunted house film – its visual flourishes setting it apart from contemporaneous American ghost pictures. That said, it’s easy to see why cinephiles whose first viewing of this film took place within a frame of expectations set by Bava’s other pictures, have found Shock to be something of an anathema within its director’s body of work. However, as Stephen Thrower argues very clearly in the extra features of Arrow Video’s release, this sense of diversity (of theme and approach) is arguably a key characteristic of Bava’s cinema, when taken as a whole.

Though its narrative is predicated on some cliches, Shock is a memorable horror film that is anchored just as much by the performances of Steiner and Nicolodi, as by Bava’s characteristic emphasis on visual flourishes. The actors build sympathetic, believable characters who have very evident flaws – and as a consequence, feel rounded and human. This is despite Mario Bava’s documented disregard for actors and dislike of directing them, a chore which on this picture he apparently delegated to his son, Lamberto, whilst he himself focused on the more technical aspects of the production. A fascinating film that has been overlooked within Bava’s filmography for some time, Shock has, in this new Arrow Video Blu-ray release, a superb presentation that is accompanied by some equally impressive contextual material. In particular, the interviews with Lamberto Bava, Dardano Sacchetti, and Stephen Thrower offer excellent insight into the film. For fans of European horror films, this is clearly one of the first essential home video releases of the year. Please click on the below screengrabs to enlarge them.

|

|||||

|