|

|

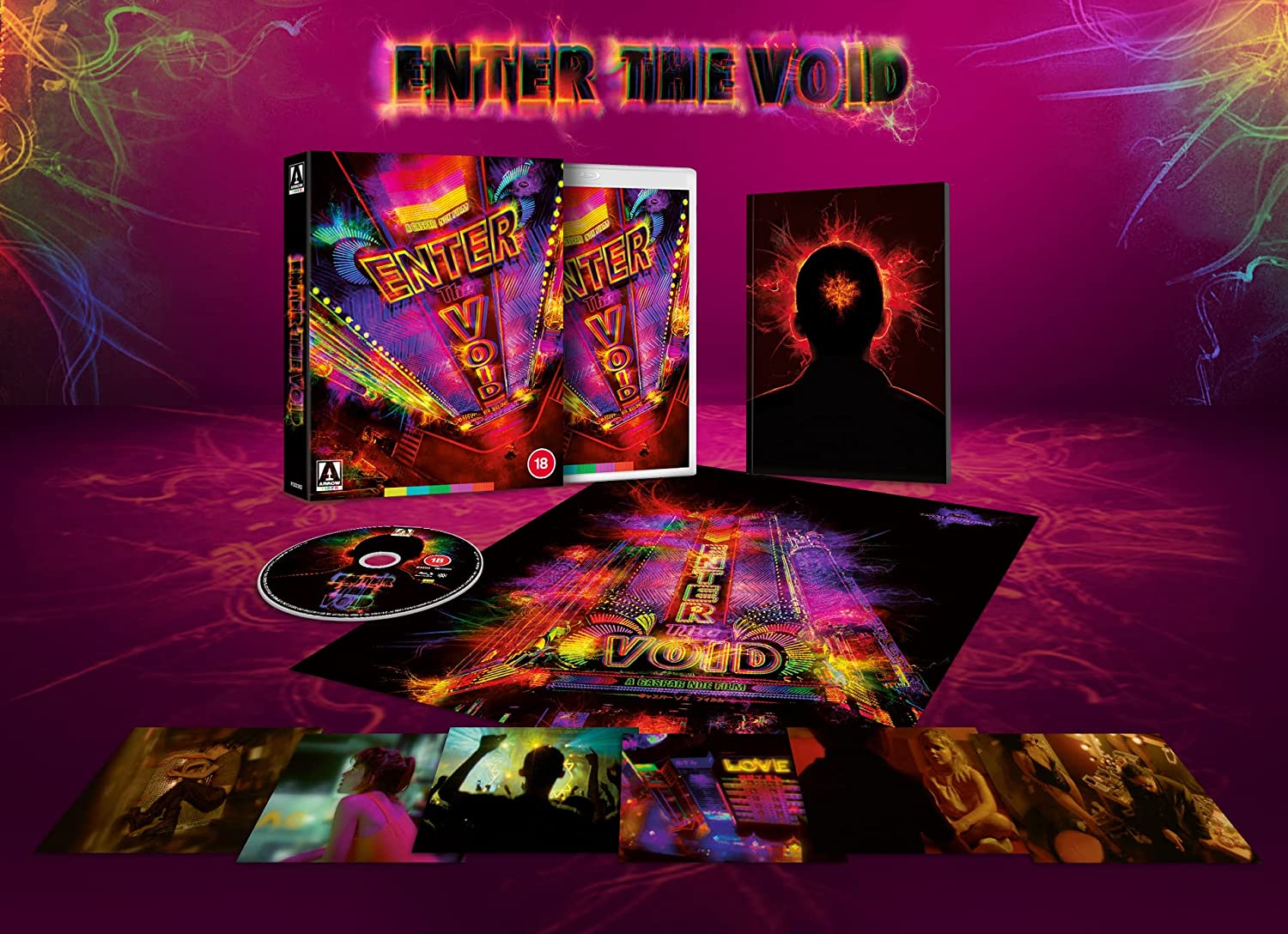

Enter the Void (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Video Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (3rd June 2022). |

|

The Film

Enter the Void (Gaspar Noé, 2009)  Synopsis Synopsis

Oscar (Nathaniel Brown), a young American living in Tokyo, is shot and killed by police during a drug deal with Victor (Olly Alexander). Via flashback, we are shown how Oscar came to be there, after turning to drug dealing in order to bring his estranged younger sister Linda (Paz de la Huerta) to Tokyo with the intention of supporting her. In childhood, Oscar and Linda’s parents were killed in a car crash. Following this, they were taken in by their grandparents, who subsequently died too. Oscar and Linda were then separated. In young adulthood, Oscar found himself in Tokyo with his friend Alex (Cyril Roy). Alex introduced Oscar to spiritualism and hallucinogens (specifically, DMT). Despite Alex’s warnings, Oscar fell in with Bruno (Ed Spear), dealing drugs for him in order to earn enough money to send for Linda, based on a promise he made to her in childhood that they would never be parted. In Tokyo, Linda began working in a strip club and formed a romantic attachment to its manager, Mario (Masato Tanno). Meanwhile, Oscar developed a fascination with Victor’s mother, Carol (Sara Stockbridge), and eventually the pair had sex. When Victor’s father (Stuart Miller) discovered this, it tore the family apart. A vengeful Victor thereafter betrayed Oscar to the Tokyo police, ultimately leading to Oscar’s death in the toilets of a nightclub. Following Oscar’s death, his consciousness floats above the city, visiting the people in his life. He sees Linda, her failing relationship with Mario, her pregnancy and abortion; he sees Alex, on the run from the police, living in the streets and eating refuse; he sees Victor, wracked with guilt and confusion. Victor approaches Linda and asks for her forgiveness; she reacts with rage. However, eventually Linda and Alex find one another, and the pair have sex in a seedy Love Hotel.  Critique Critique

Gaspar Noé’s feature debut Seul contre tous (I Stand Alone, 1998) was a dynamite mixture of searing subject matter and combative filmmaking style. A contemporary of such incendiary European arthouse pictures as Michael Haneke’s Funny Games (1997) and Lars Von Trier’s The Idiots (1998), Seul contre tous immediately established Noé as a filmmaker whose work could be discussed alongside such directors. Soon, Seul contre tous became associated with what Artforum critic James Quandt referred to in 2004 as the ‘New French Extremity’: films that were ‘wilfully transgressive’, and focused on taboo subject matter (which Quandt defines as ‘gang rapes, bashings and slashings and blindings, hard-ons and vulvas, cannibalism, sadomasochism and incest, fucking and fisting, sluices of cum and gore’) within a filmmaking framework targeted predominantly at an ‘art’ cinema audience. Quandt mentioned Noé’s work alongside such French films as Ozon’s Sea the Sea (1997), Breillat’s Romance (1999), and Claire Denis’ Trouble Every Day (2001): for Quandt, these films hinted at a ‘cultural crisis’ in French cinema, an attempt to establish a uniquely French cinematic identity that differentiated French cinema from Hollywood product. In 2002, Noé doubled down on the promises of Seul contre tous with the equally controversial Irreversible. A picture that achieved even greater notoriety outside France owing to the casting of Vincent Cassell and Monica Bellucci (the then-real life couple who were darlings of the international festival circuit), Irreversible is still arguably the film in which Noé’s distinctive, confrontational filmmaking style (strobing lights, swirling camerawork, barely tolerable low frequency drones on the audio track) and fascination with discomfiting subject matter (in that film, a hideous rape and an equally horrendous act of violent revenge) coalesced the most strongly. The casting of Cassell and Bellucci gives pathos to its story of lovers whose relationship is torn asunder by a random and grevious act of inhuman cruelty.  It was over half a decade before Noé would make another film, Enter the Void. This film would be Noé’s English-language debut. (Please see our review of Arrow’s Blu-ray release of Noé’s next film, Climax.) Noé’s fascination with finding new ways to tell a combative story would lead him to presenting the narrative of Enter the Void entirely through the subjectivity of its central character, Oscar—even after his violent demise, as his consciousness (or whatever exists beyond this mortal coil) glides through the neon-lit streets of Tokyo, picking out fragments of the lives of those touched by his death (sister Linda, friend Alex, betrayer Victor). The notion of presenting a film entirely through point-of-view shots (and some over-the-shoulder shots) in which we see the protagonist’s face only via his reflection in a mirror was not entirely original (notably, Robert Montgomery’s 1947 film noir The Lady in the Lake had attempted the same), but Noé’s chutzpah in sharing Oscar’s POV beyond his life and into his death offered something quite remarkable. (The overall impact is compounded by the use of a regular ‘blinking’ effect which viewers will find either ingenious or infuriating: there is very little middle ground in one’s response to a Noé film.) It was over half a decade before Noé would make another film, Enter the Void. This film would be Noé’s English-language debut. (Please see our review of Arrow’s Blu-ray release of Noé’s next film, Climax.) Noé’s fascination with finding new ways to tell a combative story would lead him to presenting the narrative of Enter the Void entirely through the subjectivity of its central character, Oscar—even after his violent demise, as his consciousness (or whatever exists beyond this mortal coil) glides through the neon-lit streets of Tokyo, picking out fragments of the lives of those touched by his death (sister Linda, friend Alex, betrayer Victor). The notion of presenting a film entirely through point-of-view shots (and some over-the-shoulder shots) in which we see the protagonist’s face only via his reflection in a mirror was not entirely original (notably, Robert Montgomery’s 1947 film noir The Lady in the Lake had attempted the same), but Noé’s chutzpah in sharing Oscar’s POV beyond his life and into his death offered something quite remarkable. (The overall impact is compounded by the use of a regular ‘blinking’ effect which viewers will find either ingenious or infuriating: there is very little middle ground in one’s response to a Noé film.)

Noé also works into this narrative sequences that present a hallucinogenic trip from Oscar’s perspective (the effects of his use of DMT) and equally hallucinatory images of a ‘vortex’: the latter, captured in a kaleidoscopic tunnel-like effect, would seem to suggest synaptic sparking and brain death. Noé’s interweaving of this material into the story, along with its philosophical bent, makes Enter the Void an interesting companion piece to Terrence Malick’s Tree of Life (2011). Both films essentially take the premise of the final trip sequence from Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and run with it. (Noé seems to have a particular affinity for Kubrick: posters for 2001 and Kubrick’s noir The Killing feature prominently in the set decoration for Irreversible.) The colourfully neon-lit urban milieu, and focus on a criminal subculture, suggest some association between Enter the Void and the paradigms of neo-noir: this is something that was of course also present in Seul contre tous and Irreversible. However, aesthetically Enter the Void also draws on music videos (Jonas Åkerlund’s video for The Prodigy’s ‘Smack My Bitch Up’, 1997) and cyberpunk neo-noir/science-fiction (the first-person point-of-view from Kathryn Bigelow’s Strange Days, 1995). In a video essay on this disc, Alexandra Heller-Nicholas argues that Noé’s work foregrounds the idea of cinema as a ‘sensory journey’: whilst Heller-Nicholas makes the case for this convincingly, for this writer Noé’s work is also deeply intellectual in a Bukowski-esque ‘street philosopher’ manner—to such an extent that Noé is unafraid of alienating those viewers who simply ‘don’t get it’.  Here, in Enter the Void, Noé examines life, death, and the (im)possibility of an afterlife. For some commentators, the continuation of Oscar’s point-of-view after his ugly death on the floor of a nightclub toilet, suggests that consciousness extends beyond our corporeal existence. The film’s frequent references to the Tibetan Book of the Dead, which Oscar expresses a fascination with (after having borrowed a copy from Alex), hints at a spiritual dimension to the proceedings. However, Noé himself is apparently a committed materialist, and there is much ambiguity in many of these scenes—particularly in the final scene of the film which, without wishing to ‘spoil’ it for first-time viewers, hints (for some commentators) at a theme of rebirth but seems just as likely to either suggest the concept of ‘eternal return’, or simply that the dying brain re-experiences the span of life. (Noé films the scene in such an ambiguous manner, that any and all of these interpretations may be considered valid.) Here, in Enter the Void, Noé examines life, death, and the (im)possibility of an afterlife. For some commentators, the continuation of Oscar’s point-of-view after his ugly death on the floor of a nightclub toilet, suggests that consciousness extends beyond our corporeal existence. The film’s frequent references to the Tibetan Book of the Dead, which Oscar expresses a fascination with (after having borrowed a copy from Alex), hints at a spiritual dimension to the proceedings. However, Noé himself is apparently a committed materialist, and there is much ambiguity in many of these scenes—particularly in the final scene of the film which, without wishing to ‘spoil’ it for first-time viewers, hints (for some commentators) at a theme of rebirth but seems just as likely to either suggest the concept of ‘eternal return’, or simply that the dying brain re-experiences the span of life. (Noé films the scene in such an ambiguous manner, that any and all of these interpretations may be considered valid.)

The ‘void’ of the film’s title may simply refer to the club referenced in the film (The Void) or to life or death, drawing a rough equivalence between the two. The imperative to ‘enter the void’ feels in this context like a threat. The film’s vision of human interactions may be bleak, and the flashbacks to Oscar’s childhood with Linda (the deaths of their parents, then their grandparents, leaving them orphans) are heartbreaking; but Noé’s films always have an undercurrent of transcendence bubbling beneath the surface. This may take the form of something that represents hope or promise that is snatched away (such as Alex’s pregnancy in Irreversible) or simply the suggestion (as in Enter the Void) that there is… something ethereal that is constantly, irresistibly, inutterably slipping through our fingers.

Video

Enter the Void is presented on Arrow’s Blu-ray release via a 1080/50i transfer that uses the AVC codec. The presentation uses the film’s intended aspect ratio of 2.39:1. Enter the Void is presented on Arrow’s Blu-ray release via a 1080/50i transfer that uses the AVC codec. The presentation uses the film’s intended aspect ratio of 2.39:1.

Two versions of Enter the Void are included on the disc: the UK theatrical cut (running 137:23 mins); and the director’s cut (running 154:39 mins). Both versions of the film are presented at 25fps, which apparently is Noe’s preference. (The longer version fills 34.8Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc.) The film was originally shown at Cannes in a version running over 160 minutes, but this was essentially a work in progress, with incomplete visual effects and sound mix. The final assembly was 154 minutes (the ‘director’s cut’ on this disc), but Noé had also promised the film’s investors that he would turn in an edit of the film under 140 minutes. The result of this was the alternate 137 minute cut, which was distributed theatrically in both Britain and the US. To reduce the film’s running time to 137 minutes, Noé removed the whole seventh reel from the film. The 17 minutes of footage removed from the film begins after the graphic abortion sustained by Linda, continues through the threesome between Linda, Mario, and a Japanese girl, extends beyond Oscar’s experience of Linda’s dream (in which Oscar comes back to life in the morgue, and Linda rejects him), and ends after Linda disposes of Oscar’s ashes by washing them down the sink. Noé has previously stated that this material makes little impact on the film’s narrative, though arguably it fleshes out the dynamic between Linda and her boyfriend Mario, and in the dream sequence explores Oscar’s anxieties of being rejected by Linda (topped off with Linda’s unsentimentally matter-of-fact disposal of Oscar’s ashes). The film was shot, in colour, on a mixture of Super 35 and Super 16 formats (with the use of many sequences of digital effects), and finished digitally. This hybrid shooting style results in an uneven texture throughout the picture: most of the film takes place in low-light situations at night (with some exceptions being brief, fragmented flashbacks to Oscar and Linda’s childhood), and many of these sequences have thick, heavy globs of grain. (This contrasts with the hyperclinical lines of the digitally-captured hallucination/vortex sequences.) The filmic texture of this material is articulated very well in this presentation, which has a strong encode to disc. Colours are rich and vivid, especially in those (numerous) sequences featuring strong neon lighting, and there is an excellent level of detail throughout. Enter the Void is a film that features vertiginous photography and an aesthetic that is often deliberately ‘ugly’—from the aforementioned ‘blinking’ effect to Noé’s familiar use of stroboscopic lighting. Arrow’s presentation of the film is excellent, true-to-source, and deeply film-like.

NB. There are some full-sized screengrabs at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

This was Noé’s first English-language film, and it’s been said that the director allowed the actors to improvise many of their lines on the set of the picture. The result is a film in which dialogue is sometimes a little ‘clunky’ (particularly some of Linda and Alex’s lines). Some dialogue is in Japanese with English subtitles. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included. These are easy to read and free from issues. There are two audio tracks: a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track, and a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. Both of these tracks are fine and display very good range, though the 5.1 track features a more immersive mix—particularly in terms of Noé’s use of unsettling sounds and frequencies.

Extras

The disc includes the following contextual material: The disc includes the following contextual material:

- ‘Enter the Sensorium’ (14:45). Alexandra Heller-Nicholas narrates a video essay exploring the idea that ‘Noé makes films as much for our bodies as for our minds’, and argues that Enter the Void exemplifies this tendency within the director’s body of work (ie, the notion of cinema as a ‘sensory journey’). Heller-Nicholas highlights the symbolism of the ‘void’ within the film, and its connection with the many circular visual motifs within the photography. She examines the visual style of the film, from its headache-inducing titles to its first-person viewpoint; and from its simulation of blinking within the editing patterns to the subjective depiction of a hallucinogenic ‘trip’. - ‘Tom Kan: The Art of the Titles’ (37:07). Tom Kan, the graphic designer who designed the typography for Enter the Void, talks about his work with Noé. Kan has worked with Noé on this film and Climax, and here he talks about how he came to be interested in film titles, referencing the titles for The Exorcist and Star Wars for their graphic qualities. (Kan says that in his youth, he would copy the typeface/logo for Star Wars as often as copying the logo for Iron Maiden, for example.) Kan talks about the graphics culture of Japan, and the use of typography in post-Vietnam American cinema as particular influences. This is a fascinating interview that touches on the importance of graphic design in film production (and postproduction), something that is often heavily overlooked. Kan speaks in French; optional English subtitles are provided. - Deleted Scenes (11:27). This montage of scenes that were cut from the finished film includes extra material focusing on Oscar and Linda as children; a conversation between Oscar and Alex, in which Oscar tells Alex that he has his ‘eye on’ Victor’s mother, and the pair talk about drugs; a discussion about drugs between Oscar and a Japanese woman; Oscar looking into the mirror, and his reflection reaching out to touch him; a first-person journey along what seems to be a sewer tunnel; Linda and Bruno arguing whilst driving in his car; footage of Linda being groped by a client during a lapdance at the club; and a disorienting, rotating aerial shot of the city. - ‘Making of – Special Effects’ (10:33). This featurette explores the visual effects of Enter the Void via the use of montage and 3D computer modelling. - ‘Vortex’ (5:18). Here, the viewer is presented with a five minute-long clip of the ‘vortex’ footage – the material within the film that is used to suggest the transition from life to death. - ‘DMT Loop’ (7:01). This is a seven minute-long version of the kaleidoscopic ‘trip’ footage. - Trailers: French (1:41); International (1:29); Teasers (6:35); Unused Trailers (4:59). - Image Gallery (13 images). This is a gallery of posters and promotional art.

Overall

Noé’s films are perhaps a ‘tough sell’ and often provoke a deeply personal response, so it seems impossible to contribute to this ‘Overall’ section without writing in the first-person about my own relationship with Noé’s cinema. (This may be the understatement of the century.) Noé’s films are sometimes a deliberate test of the viewer’s endurance, and are as (intentionally) abrasive in their aesthetic as they are in their subject matter. This writer vividly remembers seeing Seul contre tous at a cinema in Dublin in 1999, within a week or so of a screening of Tsukamoto Shinya’s similarly combative Bullet Ballet (1998, see our review of Third Window Films’ Blu-ray release of that film here). (I can still recall the stark posters for Seul contre tous, the blank face of the Butcher staring from them, pasted on walls near to the old Virgin multiplex on Parnell Street.) The sheer bleakness of both films (I hesitate to use the word ‘nihilism’, because despite it commonly being used in attachment to Noé’s work, I don’t think the filmmaker’s view is at all nihilistic in the true sense) felt very much a part of that pre-millennial fin-de-siecle. Approximately ten years later, Noé’s cinema had lost none of its ‘bite’ but perhaps felt buried within its own paradigm. I will admit to finding Enter the Void frustratingly self-indulgent when I saw it in 2009; revisiting it for the first time, via the longer director’s cut on Arrow’s new Blu-ray release, gave me a new appreciation for the picture. (Perhaps it was the extra footage that led me to rethink my feelings about Enter the Void, despite Noé’s suggestion that this material isn’t that important; or perhaps it was simply the fact that I revisited the film after seeing Noé’s subsequent two features, Love and Climax.) Enter the Void is certainly a combative film on many levels, and is intentionally so, but definitely worth revisiting via this Blu-ray release even if (like me) you had lukewarm feelings towards the film during its initial release. Noé’s films are perhaps a ‘tough sell’ and often provoke a deeply personal response, so it seems impossible to contribute to this ‘Overall’ section without writing in the first-person about my own relationship with Noé’s cinema. (This may be the understatement of the century.) Noé’s films are sometimes a deliberate test of the viewer’s endurance, and are as (intentionally) abrasive in their aesthetic as they are in their subject matter. This writer vividly remembers seeing Seul contre tous at a cinema in Dublin in 1999, within a week or so of a screening of Tsukamoto Shinya’s similarly combative Bullet Ballet (1998, see our review of Third Window Films’ Blu-ray release of that film here). (I can still recall the stark posters for Seul contre tous, the blank face of the Butcher staring from them, pasted on walls near to the old Virgin multiplex on Parnell Street.) The sheer bleakness of both films (I hesitate to use the word ‘nihilism’, because despite it commonly being used in attachment to Noé’s work, I don’t think the filmmaker’s view is at all nihilistic in the true sense) felt very much a part of that pre-millennial fin-de-siecle. Approximately ten years later, Noé’s cinema had lost none of its ‘bite’ but perhaps felt buried within its own paradigm. I will admit to finding Enter the Void frustratingly self-indulgent when I saw it in 2009; revisiting it for the first time, via the longer director’s cut on Arrow’s new Blu-ray release, gave me a new appreciation for the picture. (Perhaps it was the extra footage that led me to rethink my feelings about Enter the Void, despite Noé’s suggestion that this material isn’t that important; or perhaps it was simply the fact that I revisited the film after seeing Noé’s subsequent two features, Love and Climax.) Enter the Void is certainly a combative film on many levels, and is intentionally so, but definitely worth revisiting via this Blu-ray release even if (like me) you had lukewarm feelings towards the film during its initial release.

Arrow’s Blu-ray release of Enter the Void is stupendously good. The inclusion of both the shorter cut and the longer ‘director’s cut’ is to be commended, and the presentation of both is more than satisfactory. There is a small caveat that both versions of the film are presented in 1080/50i, owing to the 25ps framerate (which is apparently Noe's preference). The film is also accompanied on the disc by some excellent contextual material, including (but not limited to) Alexandra Heller-Nicholas’ thoughtful video essay and the super interview with graphic designer Tom Kan. (Seriously, this is a superb little interview… Don’t overlook it!) Please click on the screen grabs below to enlarge them.

|

|||||

|