|

|

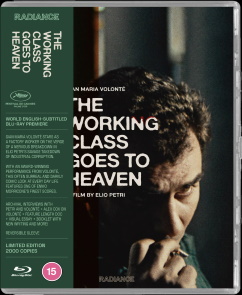

The Working Class Goes to Heaven

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Radiance Films Review written by and copyright: Eric Cotenas (5th January 2023). |

|

The Film

Ludovico Massa, or "Lulu", (Wake Up and Die' Gian Maria Volonté) is a standout worker at the BAN factory in Novara. His productivity impresses the management so much that they consult him in assessing the performances of his coworkers down to the millisecond and put him in charge of training the newcomers. His popularity is only with those above him, however, as the union foreman Bassi (The Stendhal Syndrome's Luigi Diberti) – who is also married to Lulu's ex and supporting his son – thinks he is setting unrealistic standards for his co-workers who already think he is a brownnoser, his girlfriend Lidia (Swept Away's Mariangela Melato) is frustrated by Lulu's stringent routine of work, TV, and sleep with little time for her or her son who lives with them, and the student protestors urging the workers to strike for better wages and to abolish piecework (the practice wherein workers are paid by the amount they produce rather than by the hour) at which Lulu sneers as paid troublemakers. When Lulu loses his thumb in an accident, however, his psyche starts to crumble even as the students and the striking workers hold him up as a victim of the system while the both sides of the union – split between the likes of Bassi who cares for the workers including (grudgingly) Lulu, and those in collusion with the management like the syndicalist (Django's Gino Pernice) – see just how short-sighted it was to fire Lulu when his productivity slips (not because he "cannot," he assures them, but because he no longer "wants to"). His personal life also takes a beating as he is of no use to his ex-wife and son if he cannot financially support them while Lidia has just about had it when he brings his striking comrades home to commiserate round the clock while she still works for a daily wage as a hairdresser. When the factions of the union find a (mostly one-sided) compromise and the students move onto other causes, Lulu starts to understand just how his factory mentor Militina (Fellini Satyricon's Salvo Randone) went insane and became obsessed with knocking down the walls between this world and the heaven in which they will finally be able to enjoy the fruits of their labors. The translation of the Italian title as The Working Class Goes to Heaven is suggestive of the notion of toiling and suffering in this life for reward in the next, but the subtitle under the Italian title on some posters "Lulu the Tool" is just as telling in that Volonté's protagonist has taken to heart the company's edict that "Your health depends on your relationship with your machine," so much so that he feels that he is the machine. The rhythm he establishes with the machine is almost sexual and he is not pleased to be interrupted mid-work by a pair of new workers (The Tough Ones's Corrado Solari and The Night Porter's Nino Bignamini) – who sneer behind his back and may have installed themselves with anarchy in mind – or one of his seasoned co-workers who tells him: "You're not going to die in bed. You're going to die here. On the machine." Coming in between director Elio Petri's previous, award-winning Volonté vehicle Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion and his anarchic Property is No Longer a Theft (star Flavio Bucci can be seen in the background as one of Lulu's co-workers), The Working Class Goes to Heaven is deeply cynical with no side spared. The students seem flighty rushing between causes, the management hides behind plexiglass and the recorded loudspeaker messages bestowing the virtues of work - which seems to be work for work's sake as no one at the factory can identify for what the engines they build are actually used if the vehicle even exists yet – the timekeepers are drunk with power, the workers seem an angry but easily-swayed mass, and the "engineer" is absent and only heard of when he is "transferred" as part of the union's and management's improvements for the workers. The capitalist world of the film as depicted by co-writers Petri and Ugo Pirro (The Garden of the Finzi-Continis) is so richly-developed as to be both fantastic yet completely relatable in the insidious nature of worker alienation through managerial manipulation and consumer envy so that the only objectors look like troublemakers or madmen. The contributions of masterful cinematographer Luigi Kuveiller (Deep Red), production designer Dante Ferretti (The Age of Innocence), and composer Ennio Morricone (Once Upon a Time in America) recede into the background of the drama, supporting it rather than calling attention to themselves as they do in Petri's more playful films like the aforementioned Property is No Longer a Theft or A Quiet Place in the Country. It is, however, Volonté in penultimate role for Petri – with whom he would not work again for another five years on Petri's penultimate film Todo Modo – that is the standout in perhaps his most complete and well-rounded Petri role, showing Lulu at the height of his macho powers disaffected in musing on his exploitation as a worker and gradually unravelling into impotence and petulance where he must assure himself of his sexual prowess even when his co-worker (Camorra's Mietta Albertini) tells him she felt nothing. He believes that he sets high performance standards at work for himself out of boredom and that the extra money he makes is a reward; however, after he has lost his job and Lidia has left him, he contemplates a move to Switzerland by estimating the value of things he has purchased both in the amount of piecework hours worked and how much he would likely get for them for sale. Even at Lulu's most pathetic, Volonté conveys a character who could just as easily capitulate for the sake of safety as go out with a bang (Militina advises Lulu of his own potential mental breakdown, "When they admit you... bring weapons"). Just as Petri's direction and Volonté's performance built up suspense for a potential workplace mishap in several sequences before it, so to do they achieve a similar tension in the ending sequence where one fears Lulu will either finally snap or suffer a worse accident. Although The Working Class Goes to Heaven is rooted in a historical Italian context (and a local one as the extras describe), the film is no less relevant or stimulating today than it was then.

Video

Released in Italy in 1971 but not until 1975 in the United States by New Line Cinema during their more adventurous pre-A Nightmare on Elm Street arthouse/exploitation days – and apparently not in the UK until a 2008 "Cinema '68" film festival program – The Working Class Goes to Heaven received its first English-friendly edition on in the Italy in 2009 from Raro as part of their "Minerva Classics" line – reissued with the more familiar red and black cover design in 2012 – while Germany's Koch Media Elio Petri Edition curiously included English subtitles for We Still Kill the Old Way and both English audio and subtitles for A Quiet Place in the Country but only included German subtitles for The Working Class Goes to Heaven. Radiance Films' debut Blu-ray – Region B-coded and UK only unlike some subsequent dual-territory titles – presents a 1080p24 MPEG-4 AVC 1.85:1 widescreen encode of a new master from a 2K scan of the original 35mm interpositive – utilizing a video transfer of a 35mm release print for grading reference – and the results are gorgeous given the predominantly gray, black, and white color scheme of the colorless factory and Militina's sanitarium, the stark white snowy exteriors, and the darkened environs of Lulu's apartment with occasional popping primaries utilized primarily for the goods on which Lulu spends his wages (even the saturation of the blood from Lulu's severed thumb is diluted by the machine's lubricating oils and cooling water). The pallor of the actors leans towards the pinkishly-pale even for the tanned Volonté (more so than for Melato) but that may an indicator not only of the wintry setting but also the life-sapping nature of their work. Fine detail is evident in the lines and scruff of Volonté's face, hair, the fibers of clothing, and the sheen of consumer goods. We are not certain whether the same raw scan may or may not have also been the basis for the 2020 Italian Blu-ray from CG Entertainment (issued in a 500-copy limited edition in July of that year and a standard edition in August). Unlike the Raro DVDs, the CG Blu-ray is not English-friendly.

Audio

The sole audio option is an Italian LPCM 1.0 mono track sourced from the 35mm optical soundtrack positive and cleaned by Radiance Films. The post-dubbed audio is always intelligible, the sound design is only really prominent during the factory scenes – particularly when the machines seem a threat to their humans – and Morricone's score has presence in the unnerving way it moves in and out of the soundscape. Optional English subtitles are free of errors.

Extras

Extras start off with a 1972 TV interview with director Elio Petri from the Cannes Film Festival (6:38) in which he discusses the film and its themes of output for the sake of output, Lulu likening himself to an "excrement-producing machine," and affirms his stance with the working class. A 1984 interview with actor Gian Maria Volonté from French TV (35:13) following his Cannes win for The Death of Mario Ricci during which he discusses his early works – noting that he did the Leone westerns to make money between stage works and that the billing of him as "Johnny Welles" had everything to do with the producer's attempt to Anglicize the film rather than any attempt by himself to distances himself from such work – and his collaborations with other directors including Petri and Francesco Rosi. In an interview with actor Corrado Solari (15:03) from 2015, the actor warmly recalls both Petri and Volonté – in spite of initially being put off that Petri was fine with Volonté insisting on dialogue changes but not himself – who both helped him with financial difficulties at different times in his life while the new Appreciation of Gian Maria Volonté and the film by filmmaker Alex Cox (10:10) is pretty much what the title states. Cox can tell us little more about Volonté than is popularly known through other accounts – including the drug use and suicide of his actor brother Claudio Camaso (A Bay of Blood) – instead emphasizing the image of the actor through his roles. More informative is "Petri's Praxis: Ideology and Cinema in Post-war Italy" (20:37), a visual essay by scholar Matthew Kowalski who discusses the disillusionment of Petri and others with the Italian communist party after the excesses of Stalinism were revealed and the development of class consciousness through mass culture and lived experience as progressively-realized by the characters in Petri's films. "The Working Class Goes to Heaven: Background to a Film Shot in Novara" (49:37) is a documentary by Serena Checcucci and Enrico Omodeo Salé from 2006 in which we discover that the Novara factory location was available because it was the scene of a local scandal involving the mismanagement and mishandling of finances by the absconding president who fled to Switzerland. It was discovered that the money meant for the factory went through other branches in other countries and into his pockets. The story of the local factory and the making of the Petri film is told by local workers, union members, municipal members, journalists, as well as some of the local extras who appeared in the film. The disc closes out with the film's theatrical trailer (3:39).

Packaging

The disc is housed in a case with a reversible sleeve featuring original and newly commissioned artwork by Time Tomorrow while the first pressing of 2,000 copies is packaged in a full-height Scanavo case with removable OBI strip leaving packaging free of certificates and markings and includes a limited edition booklet in which critic Eugenio Renzi provides some historical context to the waking of the working class in the late sixties as embodied in the film and cites the existence of "erotic proletarian manhood" as a film genre unto itself. Roberto Curti, author of "Elio Petri: Investigation of a Filmmaker", discusses the "match made in heaven" between Petri and politically-outspoken Volonté (possibly suggesting that A Quiet Place in the Country might have also been conceived with the actor in mind rather than Franco Nero) and how the success of the film was born of the tension between them. Reprinted from Cahiers du Cinema is an extract a 1972 essay by Pascal Kané – which also included discussion of Francesco Rosi's The Mattei Afffair (also with Volonté) who discusses the film in contrast to the Hollywood means of popularizing the workers' struggles in a dialectical conflict. Reprinted from a 1972 issue of the French journal Cinema is an interview with Petri who describes the film as an "observation" rather than a socio-political work. Reprinted from a 1973 issue of Film Quarterly is a stimulating review by James Roy MacBean who discusses the film's factory-as-prison metaphor, the trap of industrial capitalism, and the psychology of Lulu's character.

Overall

Although The Working Class Goes to Heaven is rooted in a historical Italian context (and a local one as the extras describe), the film is no less relevant or stimulating today than it was then.

|

|||||

|