|

|

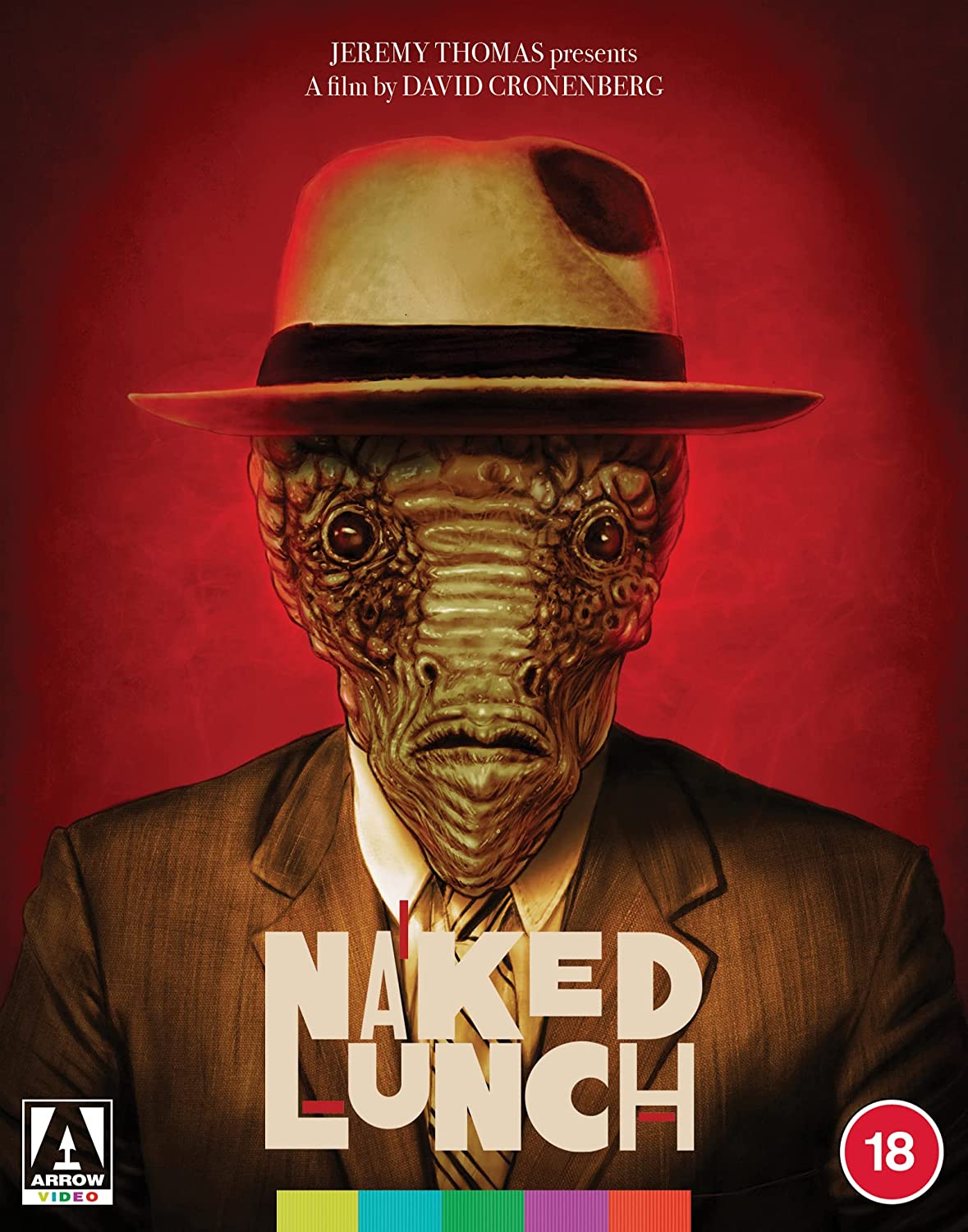

Naked Lunch (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (14th May 2023). |

|

The Film

Naked Lunch (David Cronenberg, 1991)  Released in 1992 (barring a few festival screenings in December of 1991), David Cronenberg’s adaptation of William S Burroughs’ “unfilmable” postmodern novel (The) Naked Lunch managed the impossible by taking some of the raw material of the source book and integrating it with details from the life of its author. To be fair, this wasn’t difficult, as Burroughs’ early work, in particular, had a heavy autobiographical bias: his early novels Junky and Queer drew on his own experiences as an addict, and as a gay man who often struggled with his own sexuality. Later work (such as the short story “Exterminator!”, drawing on Burroughs’ own experiences as an insect exterminator) would prove to be equally autobiographical. Released in 1992 (barring a few festival screenings in December of 1991), David Cronenberg’s adaptation of William S Burroughs’ “unfilmable” postmodern novel (The) Naked Lunch managed the impossible by taking some of the raw material of the source book and integrating it with details from the life of its author. To be fair, this wasn’t difficult, as Burroughs’ early work, in particular, had a heavy autobiographical bias: his early novels Junky and Queer drew on his own experiences as an addict, and as a gay man who often struggled with his own sexuality. Later work (such as the short story “Exterminator!”, drawing on Burroughs’ own experiences as an insect exterminator) would prove to be equally autobiographical.

Cronenberg’s film also foregrounds the death of Burroughs’ wife which occurred whilst the couple were living in Mexico. Joan Burroughs (nee Vollmer) was shot by her husband whilst the couple performed a one-off “party trick” based on the fable of William Tell. Burroughs reputedly told Joan, “It’s time for our William Tell act,” and Joan responded by balancing a highball glass on her head. Aiming a revolver at his wife, Burroughs fired and hit Joan in the forehead, killing her. Some of the details of the incident are hazy, confused by stories of bribed witnesses, the apparently combative relationship between Joan and her husband, Burroughs’ changing accounts of what actually happened, and Joan’s reputedly suicidal state of mind. The incident dogged Burroughs for the rest of his life, and allusions to it crop up time and time again in his books. Following Joan’s death, Burroughs claimed he was compelled to pursue his writing career by something he referred to as “the Ugly Spirit,” which he suggested had possessed him. Published in 1959, Burrough’s third novel The Naked Lunch integrated the author’s fascination with the lives of social outcasts (addicts and gay men struggling with their sexuality, in particular) with a paranoid narrative about a shadowy liminal place called Interzone. Interzone was based on the Tangier International Zone, where Burroughs lived following the publication of Junky in 1953. Burroughs’ life in the Tangier International Zone was predicated on an income from his family, which made him financially independent, and the ready availability of various narcotics.  The book’s structure is episodic, the plot presented via a series of vignettes involving the protagonist, William “Bill” Lee, who flees from the police and winds up in Mexico. There, Lee meets with Dr Benway, a sadistic “Demoralizator,” and becomes involved in the trade of “Black Meat.” Burroughs experimented with nonlinear narrative, produced via means of his “cut-up” technique which essentially randomised passages and allowed them to float within the text. Naked Lunch was considered outrageous: it was declared obscene in some states of the US, and the explicit nature of some of its content was – aside from its “cut-up” structure – considered one of the reasons why it was claimed to be unfilmable. The book’s structure is episodic, the plot presented via a series of vignettes involving the protagonist, William “Bill” Lee, who flees from the police and winds up in Mexico. There, Lee meets with Dr Benway, a sadistic “Demoralizator,” and becomes involved in the trade of “Black Meat.” Burroughs experimented with nonlinear narrative, produced via means of his “cut-up” technique which essentially randomised passages and allowed them to float within the text. Naked Lunch was considered outrageous: it was declared obscene in some states of the US, and the explicit nature of some of its content was – aside from its “cut-up” structure – considered one of the reasons why it was claimed to be unfilmable.

The narrative of Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch takes the death of Joan (played by Judy Davis) – enacted by Bill Lee (Peter Weller) with some substantial ambiguity hanging over the incident (is it an accident, or does Lee intentionally kill his wife?) – as the catalyst for the film’s protagonist’s journey from bug exterminator to writer. (In early scenes, we see Bill being encouraged to write by his friends Hank and Martin – codified versions of Burroughs’ real-life contemporaries Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac.) Fleeing to “Interzone” and addicted to God only knows however many toxic/narcotic substances, Lee is recruited as a writer of reports by a Clark Nova typewriter-turned-huge talking beetle. In Interzone, Lee falls into the orbit of sleazy writer Tom Ford (a thinly-veiled version of the writer Paul Bowles, who Burroughs met in Tangiers; played by Ian Holm) and his wife Joan, who is a dead ringer for Lee’s own dead spouse. The Clark Nova suggests Tom and Joan are allies of Dr Benway (Roy Scheider), a shadowy figure who is central to the trade in the narcotic black flesh of the Brazilian aquatic centipede – and who harvests this material in Interzone for sale in the US. Another figure associated with Benway is the wealthy Yves Cloquet (Julian Sands), who preys on the young local men and has a particular eye for Kiki (Joseph Scorsiani), a gentle youth who has a soft spot for Bill Lee. (Kiki is based on a lover Burroughs took in Tangiers.) As the film ends, Lee thwarts Benway’s operation and elopes with Joan, who may be Tom’s wife or Bill Lee’s own wife – or may be a giant centipede in disguise. They flee to Annexia, another fictional territory familiar from Burroughs’ fiction. (Here, Annexia is presented via a snowy checkpoint and two burly armed border guards, which evokes Stalinist Russia.) Burroughs is asked by the guards to prove he is a writer; in response, he produces a fountain pen (“I have a writing device,” he says). This doesn’t impress the guards; as further proof, Lee turns to Joan, seated in the back of the vehicle he has been driving, and tells her it is once again time to enact their “William Tell routine.” The film’s resolution suggests Lee is destined to relive his wife’s death, the catalyst for his art – which Cronenberg’s picture implies is central to Burroughs’ own art.  As the above synopsis might suggest, Cronenberg’s adaptation of Naked Lunch foregrounds the hardboiled motifs and sci-fi trappings that often worked their way into Burroughs’ writing. This is a more “literary” Cronenberg film, from a period in which the Canadian filmmaker’s cinema seemed to be evolving (post-The Fly) away from the “pure” genre cinema of his early career into something more acceptable to middlebrow audiences – including a number of projects either written by other people, or based on existing “cult” novels. Prior to Naked Lunch, Cronenberg had directed Dead Ringers (in 1988), and his subsequent films were M. Butterfly (1993) and the J G Ballard adaptation Crash (1996). (Here, it’s perhaps worth noting that both Naked Lunch and Crash were produced by Jeremy Thomas.) As the above synopsis might suggest, Cronenberg’s adaptation of Naked Lunch foregrounds the hardboiled motifs and sci-fi trappings that often worked their way into Burroughs’ writing. This is a more “literary” Cronenberg film, from a period in which the Canadian filmmaker’s cinema seemed to be evolving (post-The Fly) away from the “pure” genre cinema of his early career into something more acceptable to middlebrow audiences – including a number of projects either written by other people, or based on existing “cult” novels. Prior to Naked Lunch, Cronenberg had directed Dead Ringers (in 1988), and his subsequent films were M. Butterfly (1993) and the J G Ballard adaptation Crash (1996). (Here, it’s perhaps worth noting that both Naked Lunch and Crash were produced by Jeremy Thomas.)

That said, Cronenberg’s fascination with the mutability of both the human body and objects, and his consideration of our relationship with the abject, is very much present within Naked Lunch. From Bill Lee’s story (delivered orally in Yves’ car and taken from Burroughs Naked Lunch) about the talking asshole that ate its owner, to Mugwump-head typewriters that grow teats which leak jism, Naked Lunch maintains a focused gaze on what could loosely be termed the “body horror” aesthetic associated with Cronenberg’s work. Typewriters transform into bugs which demand that Bill Lee rub narcotic powder on the “lips” (that look for all intents and purposes like rectums) concealed beneath their wings; Benway emerges from a human skin-suit in which he masquerades as the Ford’s stern housemistress Fadela (Monique Mercure). Yves transforms into a human-bug to fuck-absorb Kiki, their bodies fused together in imagery that recalls the shape-shifting monster of John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982). The creatures designed, by James Isaac and Chris Walas, and largely achieved via animatronics, tap into the same slimy aesthetic as those of Screaming Mad George – particularly the latter’s work for Brian Yuzna in Society. Society was completed in 1989 but not released theatrically in the US until 1992, within a month of Naked Lunch. In retrospect, if Paul Verhoeven’s Total Recall (1990) is often taken as the “last gasp” of practical effects for big-budget Hollywood movies, Naked Lunch and Society feel like era-defining pictures in the use of physical effects in the “body horror” subgenre. “It’s a very literary high,” Joan tells Bill Lee after she ingests the ‘roach extermination powder he’s been using in his job as an exterminator, “It’s a Kafka high. You feel like a bug.” Her words could be equally applicable to the experience of watching Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch: the film itself may be considered a ”Kafka high.” Bill Lee, a recurring character in Burroughs’ work, is here played with wonderful deadpan sincerity by Peter Weller. Weller invests the dialogue with a flatness of intonation which works perfectly, hinting at a strong sense of repression and internalisation of conflict within the character. As Lee’s sense of reality falls apart and he sees himself, in Benway’s worlds, as an “agent who has come to believe his own cover story,” we are left with Burroughs’ own explanation of his novel’s title – the sense that Naked Lunch refers to the “frozen moment when everyone sees what is on the end of every fork.”

Video

Arrow Video have released Naked Lunch on both a 4k UHD disc and a Blu-ray. We were presented with the latter for review. Arrow Video have released Naked Lunch on both a 4k UHD disc and a Blu-ray. We were presented with the latter for review.

On the Blu-ray, Naked Lunch is presented in 1080p using the AVC codec. The film is in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The film runs for 115:13 mins and is uncut. Shot in 35mm and on colour stock, Naked Lunch was photographed by Peter Suschitzky. Suschitzky’s photography for the film employs a palette dominated by drab browns and greens, with the occasional burst of colour (for example, in the kaleidoscopic opening titles sequence). Arrow’s presentation of the film is billed as being based on a new 4k restoration from the original negative, which has been overseen by Suschitzky and approved by Cronenberg. In honesty, the film looks stupendously good on this Blu-ray release. There is an excellent level of detail present throughout: even on the Blu-ray, a very impressive amount of fine detail – including the pores of the actors’ skin – is evident in abundance in close-ups. The textures of fabrics and surfaces within the image is almost palpable. Colours are impressive too. The kaleidoscopic titles sequence features some vivid primary colours that are conveyed with depth and consistency in this presentation. The autumnal hues of the majority of the picture are articulated clearly, and skintones have a naturalistic quality throughout. There is no noticeable damage within the presentation. Contrast levels are very pleasing. Rich blacks offer quiet gradation from the toe to the midtones, and highlights are balanced and avoid being blown out. The encode to disc is equally impressive, and ensures that the presentation as a whole retains the grain structure of 35mm film. Previous digital home video versions of Naked Lunch haven’t been terrible, but this new HD release from Arrow easily eclipses them all. (One may reasonably presume that the associated 4k release builds on the strengths evident in the Blu-ray version provided for review.) NB. Some full-sized screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review. Please click these to enlarge them.

Audio

There are two lossless audio options on the disc: a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track, and a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included. Both audio tracks are equally robust, with pleasing depth, clarity, and range. The LPCM track is perhaps a little more “punchy” in some areas, particularly in sequences that employ Howard Shore and Ornette Coleman’s distinctive score. That said, though the film was originally presented in Dolby Stereo (and therefore purists will most likely default to the stereo track), the DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track includes some impressive sound separation that adds an extra layer of immersion in some sequences – such as crowd sequences, for example, with their added ambient sound.

Extras

The release includes the following on-disc material.  Disc One: Disc One:

- The Film - Audio commentary by David Cronenberg. This is the same commentary by Cronenberg that has appeared on previous digital home video releases of Naked Lunch . In it, the filmmaker reflects on the process of building a coherent narrative out of Burroughs’ source novel, and explores some of the challenges involved in bringing this material to the screen. - Audio commentary by Jack Sargeant and Graham Duff. In this new commentary track, critics Sargeant and Duff examine. They consider Cronenberg’s approach to adapting the novel, and reflect on the novel’s place within the career of Burroughs – and its relationship with Burroughs’ other novels. Sargeant suggests that Burroughs’ work is very much about “what it means to write” and the processes involved in writing. They argue that Cronenberg’s “skills as a writer” are often overlooked in favour of discussion of the visceral thrills of his films. - Theatrical Trailer (1:39). This is the stupendously memorable trailer for the film, featuring droll narration by William S Burroughs himself. Disc Two: - Filmmaker Interviews. This gallery includes new interviews with producer Jeremy Thomas (15:32), actor Peter Weller (61:53), director of photography Peter Suschitzky (11:01), special effects artist Chris Walas (18:36), and composer Howard Shore (17:09).

Jeremy Thomas talks about the challenges faced in bringing Naked Lunch to the screen. He talks about the origins of the project in a conversation he had with David Cronenberg in Toronto, following a screening of Nic Roeg’s Bad Timing , which Thomas produced. Preparation involved spending time in Burroughs’ old stamping grounds in Tangiers, and the intention was to make the film in Tangiers; this had to be rethought following commencement of the Gulf War, and the film was shot on specially-constructed sets rather than on location. Thomas discusses the performances in the film, exploring the relationships between the fictional characters they play and the real figures from Burroughs’ life. He also talks about the creation of the film’s special effects. Thomas also reflects on the success of Naked Lunch at Cannes and after, suggesting that he doesn’t view the picture as a “horror movie.” In Peter Weller’s interview, the actor talks at length about his association with jazz culture, reflecting on his early career as a jazz trumpeter and the significance of Burroughs (and Naked Lunch in particular) for the culture of the 1960s. He connects Burroughs with Pasolini, Gore Vidal, Jean Genet, and other gay artists, and discusses the bravery of these artists to be outwardly gay during the mid-20th Century. Weller also talks about Burroughs’ use of the “cut-up” technique, and reflects on Naked Lunch as a novel that reacted against the repressive culture of the 1950s. Weller examines the development of the project, discussing Cronenberg’s approach to adapting Burroughs’ novel. This is an excellent interview, with Weller at his erudite best. Peter Suschitzky reflects on how he came to work with Cronenberg, for the first time, on Dead Ringers . Suschitzky asserts that he deliberately didn’t read Naked Lunch because he wanted to focus on the script. Suschitzky talks about the use of sets in the film, suggesting that the image of Morocco that is seen on the screen is, thanks to the artifice of the sets, implied to be a product of the imagination of the characters. Suschitzky also discusses at length the challenges faced in photographing the film’s special effects. The interview with Walas sees the special effects artist reflecting on his working relationship with David Cronenberg, which began with Scanners in 1981. Walas discusses some of the challenges he faced in creating the effects for Cronenberg’s films, and the interview is illustrated with some great behind-the-scenes footage showing William S Burroughs interacting with the creature designs. He also talks about the logic behind the use of hand puppeteering or cable manipulation for the creatures in the film. Howard Shore’s interview sees the composer offering some insight into the processes involved in scoring a picture for Cronenberg. Shore discusses how he was inspired to incorporate Ornette Coleman’s music into the score.

- “A Ticket to Interzone” (28:31). David Cairns provides a video essay that explores how Naked Lunch offers an intersection between Burroughs’ work and Cronenberg’s worldview. Cairns reflects on Cronenberg’s approach to adapting Burroughs’ “unfilmable” book, considering how the filmmaker imposed a sense of narrative structure on Burroughs’ text by interweaving elements from the writer’s life. (Cairns compares Naked Lunch with Wim Wenders’ Hammett , Steven Sodebergh’s Kafka , and Paul Schrader’s Mishima .) Cairns suggests that in writing the Naked Lunch script, Cronenberg worked in elements from his work on his never-completed Total Recall script (an adaptation of Philip K Dick’s “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale”). Both Total Recall and Naked Lunch , Cairns offers, present stories of protagonists whose sense of reality is eroded following the killings of their respective wives. The video essay also includes video comments from Luke Aspell, the author of a monograph on Cronenberg’s Shivers (published as part of LUP’s “Devil’s Advocate” series), and Fiona Watson. - Tony Rayns on William S Burroughs (60:29). In a lengthy interview, the ever-knowledgeable Mr Rayns speaks about the life of Naked Lunch ’s author, William S Burroughs. Rayns traces Burroughs’ life from his youth through his early experiences (including his addiction to “junk”) and his work as a writer. This is an encyclopedic account of Burroughs’ influences, highlighting his techniques as a writer and his associations with various countercultural figures. - David Huckvale on Naked Lunch (31:27). David Huckvale, an academic and writer who has written volumes about film music and body horror, examines Cronenberg’s adaptation of Naked Lunch . He highlights Cronenberg’s “biographical” approach to adapting the book, suggesting that the film is “really about coming to terms with yourself” and a “journey towards acceptance and fulfilment as a person.” He highlights the phallic imagery in the film, and foregrounds the narrative as about Bill Lee’s “awakening” to his own homosexuality. Huckvale uses this analysis of the themes of the film as an anchor for a consideration of Howard Shore’s score and its use of jazz motifs – and its incorporation of Ornette Coleman’s intellectual, avant garde saxophone jazz. - “Naked Making Lunch” (54:40). This behind-the-scenes documentary about the making of Naked Lunch has been included on the film’s previous home video releases, and was screened as part of ITV’s South Bank Show in 1992. It’s a superb documentary, interspersing footage from the production with Burroughs reading from his own novel, interviews with various personnel, and Cronberg and Burroughs addressing a press conference about the production together. The documentary explores reactions to Burroughs’ novel and criticisms that it is “obscene.” Brion Gysin’s influence on Burroughs is highlighted, and Cronenberg talks about how he wrote the script during the period when he was acting in Clive Barker’s Nightbreed . This presentation, however, is a new scan from director Chris Rodley’s personal 16mm print. The menu provides the viewer with the option of watching this documentary with an audio interview with Chris Rodley, in which Rodley speaks about his own creative “journey” from painting to filmmaking. - Concept Art (2:51). This is a gallery of Stefan Dupois’ concept designs. - Image Galleries: Promotional Stills and Posters (7 images); From the Collection of Chris Rodley (75 images). The former is self-explanatory; the latter is a series of on-set stills taken by Chris Rodley, on the set of Naked Lunch . These have never been seen before.

Overall

“Exterminate all rational thought. That is the conclusion I have come to,” Bill Lee tells his writer friends part-way through Naked Lunch. This assertion could be taken as a defining statement in terms of William S Burroughs’ approach to writing, and it also seems to be a philosophy that David Cronenberg attempts to foreground in this cinematic adaptation of Burroughs’ most notorious novel. Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch is as much about the process of writing, and inspiration for writing, as it is about its many other subjects – drug addiction, latent/nascent sexuality, the exoticism of the Interzone, and so on. (David Huckvale, on the other hand, suggests the film’s main theme is focused on Bill Lee’s growing realisation that he is gay, and coming to terms with his own homosexuality. Neither of these interpretations is mutually exclusive, however.) Weller is perfectly cast as Bill Lee, and is surrounded by an excellent supporting cast: Roy Scheider, Judy Davis, Ian Holm, and Julian Sands all shine in their respective parts. “Exterminate all rational thought. That is the conclusion I have come to,” Bill Lee tells his writer friends part-way through Naked Lunch. This assertion could be taken as a defining statement in terms of William S Burroughs’ approach to writing, and it also seems to be a philosophy that David Cronenberg attempts to foreground in this cinematic adaptation of Burroughs’ most notorious novel. Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch is as much about the process of writing, and inspiration for writing, as it is about its many other subjects – drug addiction, latent/nascent sexuality, the exoticism of the Interzone, and so on. (David Huckvale, on the other hand, suggests the film’s main theme is focused on Bill Lee’s growing realisation that he is gay, and coming to terms with his own homosexuality. Neither of these interpretations is mutually exclusive, however.) Weller is perfectly cast as Bill Lee, and is surrounded by an excellent supporting cast: Roy Scheider, Judy Davis, Ian Holm, and Julian Sands all shine in their respective parts.

The film’s production design is equally superb, with the grimy New York setting of the opening sequences complemented with the heat of the Interzone-set scenes. Also impressive is Howard Shore’s haunting score, anchored by Ornette Coleman’s saxophone playing. In all, it’s a superb film, amongst its director’s most impressive pictures. Arrow’s new Blu-ray release of Naked Lunch contains an excellent new presentation of the main feature, and is accompanied by an enormously impressive range of special features. Please click the screengrabs below to enlarge them.

|

|||||

|