|

|

The Film

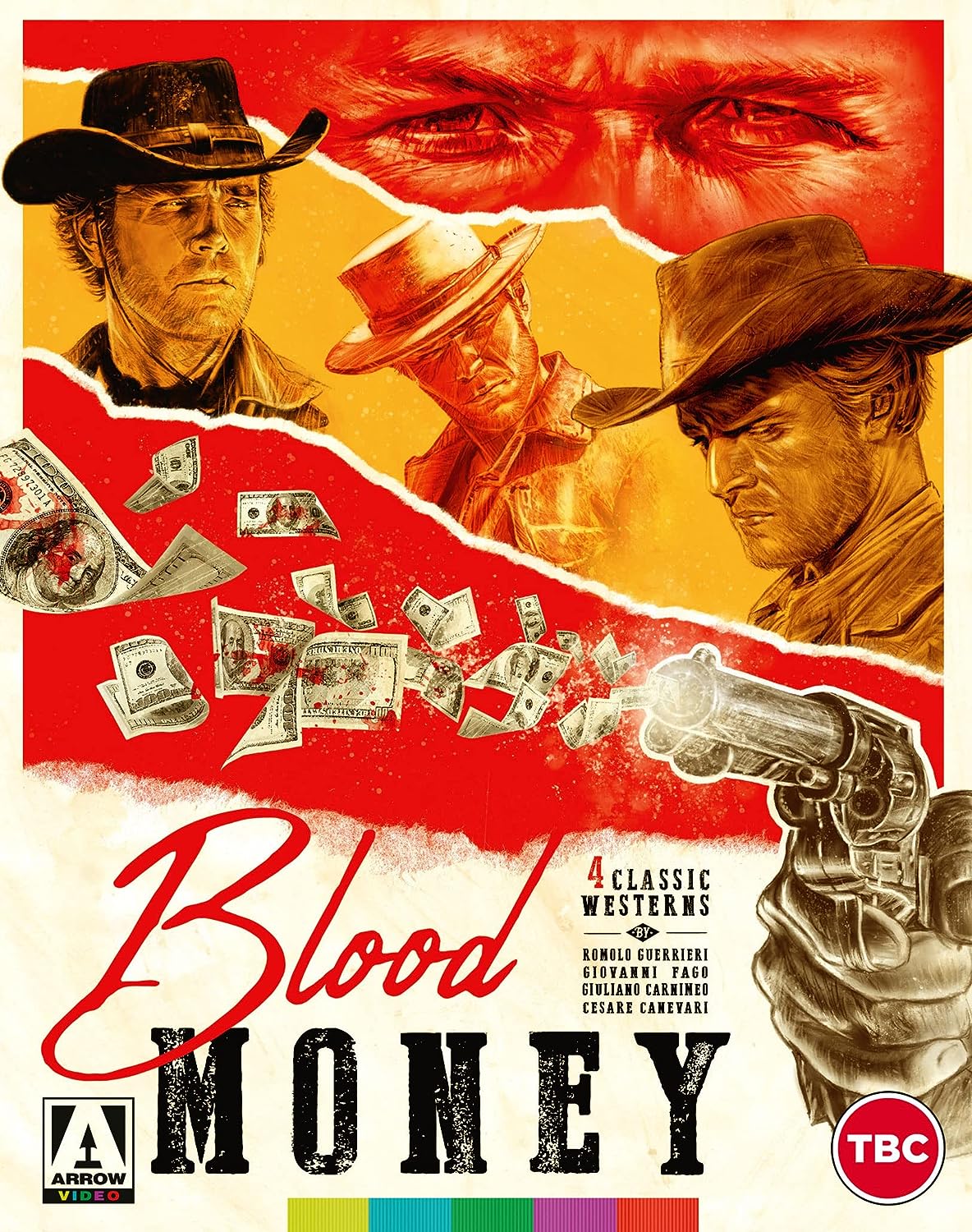

Blood Money: Four Classic Westerns  10,000 dollari per un massacre / 10,000 Dollars for a Massacre / $10,000 Blood Money (Romolo Guerrieri, 1967) 10,000 dollari per un massacre / 10,000 Dollars for a Massacre / $10,000 Blood Money (Romolo Guerrieri, 1967)

Written by Ernesto Gastaldi, at some point before production the protagonist of 10,000 Dollars for a Massacre (also released in English as $10,000 Dollars Blood Money) was renamed “Django,” making the film among the first among many to be positioned as an unofficial sequel to Sergio Corbucci’s Django (1966). Django had captured the imagination of cinemagoers in Italy and other European territories (particularly Germany, where it seems nearly every Italo-Western for several years was marketed as Django-adjacent). Unlike many other Django imitators, however, Guerrieri’s film has something of the Gothic tone of Corbucci’s film. As Django, Gianni Garko – clad in black, with a white scarf – is, like Franco Nero before him, a somewhat dapper grief-ridden hero. Where Franco Nero’s Django was tortured by the death of the woman he loved – an incident that took place before the events of the film – during the narrative of 10,000 Dollars for a Massacre Garko’s Django suffers the death of his beloved, saloon owner Mijanou (Django’s Loredana Nusciak, whose presence in this film amplifies the relationship with the Corbucci picture). This leads to a scene in which Django demonstrates outright grief, shedding an onscreen tear in a moment that the extra features on this disc go to great lengths to suggest is atypical for an (anti-)hero of a western all’italiana. The film was the first of several Italo-Westerns produced by Luciano Martino, and it was one of only two Westerns directed by Romolo Guerrieri. Guerrieri’s previous Italo-Western, Johnny Yuma (1966), is an entertaining affair, but ultimately not very memorable. (Guerrieri’s career to that point had largely been as an assistant director on numerous pepla.) 10,000 Dollars for a Massacre is a much more impactive picture, chiefly thanks to a tight and often unpredictable script. (In the interview with Ernesto Gastaldi on this disc, Gastaldi notes that he wrote the picture, and though numerous other individuals are given an onscreen writing credit for the film, it seems their contributions were fairly miniscule.) A mournful tone hangs over 10,000 Dollars for a Massacre, from its strong, enigmatic opening sequence onwards. In this opening sequence, we are presented with waves lapping the sandy shore as shorebirds take flight; then we cut to Django, lying asleep on the sand, barefoot and his hat covering his eyes. Django awakens, and the camera pulls back to reveal that he is lying next to a corpse. Django calls two horses, and throws the corpse over the second horse before riding into town with his quarry. Deftly, the film tells us that Django is a bounty hunter, and that the film’s narrative takes place in a world in which death has a seemingly casual significance.  The narrative doesn’t shy away from depicting the work of its bounty hunter protagonist as existing in a moral grey area. When the town sheriff notes that Django is “singlehandedly ridding the county of vermin,” a deputy (Joe, played by Rocco Lerro) answers that “Jackals and vultures do the same thing.” Later, Manuel highlights for Django the similarities between these two men, ostensibly on opposite sides of the law: “You kill people, just like me,” Manuel says, “You and me, we’re in the same business.” The narrative doesn’t shy away from depicting the work of its bounty hunter protagonist as existing in a moral grey area. When the town sheriff notes that Django is “singlehandedly ridding the county of vermin,” a deputy (Joe, played by Rocco Lerro) answers that “Jackals and vultures do the same thing.” Later, Manuel highlights for Django the similarities between these two men, ostensibly on opposite sides of the law: “You kill people, just like me,” Manuel says, “You and me, we’re in the same business.”

Django is set against Manuel Vasquez, a ruthless bandit, and his gang. Manuel is played by Claudio Camaso, the brother of Gian Maria Volonte, to whom Camaso bears a strong physical resemblance. Camaso’s life story would make a fascinating feature film in itself. Where Volonte was an avowed and committed leftist, Camaso was associated in his youth with neo-fascist movements, including active roles in a number of bombings. In 1977, he killed another man, an acquaintance in the film industry named Vincenzo Mazza, who had intervened in a dispute between Camaso and Camaso’s ex-wife. In jail, Camaso committed suicide by hanging himself. Django also becomes involved with saloon owner Mijanou (Nusciak). As in many Westerns, Mijanou offers Django a “way out” from his life of violence. She is heading to San Francisco, and Django vows to come with her – but after he has collected the $10,000 bounty on Manuel. Django is quick to violence but, in the ways of love and romance, he is little more than a child. “Do you have water in your veins?” Mijanou asks him when Django doesn’t respond to her flirtatious demeanour. (Later, Manuel also recognises Django’s naivete when it comes to women and sex: “You’re sly, greedy, dangerous,” Manuel tells Django, “But you don’t know women.”) Mijanou disapproves of Django’s work as a bounty hunter, telling him “You’re a wolf, and you always have been.” Nevertheless, she agrees to give Django an ultimatum: he has six days to capture Manuel, before Mijanou leaves on the next stagecoach to San Francisco. Django, however, is too rooted in his battle with Manuel to keep accurate track of the passage of time, and accidentally misses Mijanou’s ultimatum. The lure of violence (and money) is stronger than the bonds of romantic love. Tragically, Mijanou never reaches her destination. Manuel persuades Django to form an uneasy alliance, in which Django will help Manuel intercept a stagecoach carrying a large amount of gold, which Manuel vows to split with Django. Django performs his role, stopping the stagecoach by blocking the pass with dynamite; but Manuel slaughters everyone on board – including Mijanou, who unbeknownst to Django was traveling in that very stagecoach. The remainder of the film becomes a protracted game of cat and mouse between Django and his nemesis. Along the way, 10,000 Dollars for a Massacre introduces some elements that are clearly modelled on aspects of Leone’s seminal westerns all’italiana, including the eccentric photographer, Fidelio (Fidel Gonzales), who assists Django – a character apparently inspired by the coffin-maker from Fistful of Dollars. Camaso’s role as the ruthless, murderous Manuel also seems heavily rooted in Camaso’s brother, Gian Maria Volonte’s role as the psychopathic Indio in Leone’s For a Few Dollars More.  Per 100.000 dollari t'ammazzo / Vengeance Is Mine / $100,000 for a Killing (Giovanni Fago, 1968) Per 100.000 dollari t'ammazzo / Vengeance Is Mine / $100,000 for a Killing (Giovanni Fago, 1968)

Transposing the Cain and Abel story to the Almerian West, Giovanni Fago’s Vengeance Is Mine is the “twin” of 10,000 Dollars for a Massacre. Produced by the same team, it shares much of its cast with the other picture, and also features a score by the same composer. Vengeance is Mine opens at the St Tomas Hermitage, where bounty hunter John Forest (Gianni Garko) surprises a group of bandits (led by Fernando Sancho, who had also played a part in 10,000 Dollars for a Massacre) by springing out of a coffin. Riding into town, John sees a “Wanted” poster for his half-brother, Clint Forest (Claudio Camaso), which causes John to reflect on how he and Clint became estranged and on opposite sides of the law. Clint has fallen in with outlaw Jurago (Piero Lulli) and his gang. However, with a small group, Clint decides to double cross Jurago in order to claim the $100,000 in gold that the gang have stolen from a stagecoach. John manages to capture Clint, but he is told that owing to the defeat of the Confederate forces in the Civil War, he will no longer be paid the bounty he is owed. When Jurago arrives in town, planning to kill Clint, John decides to help his half-brother defend himself. Afterwards, Clint vows to go to Mexico and never turn back. His group and John will split the gold from the stagecoach on the border. However, Clint’s crew turn against John and torture him, in an attempt to make him reveal the location of the gold (which John has hidden). Even Clint seems ashamed by this. The stage is set for a final showdown between John and Clint. In its opening sequence, in which John is shown hiding in one of four coffins before placing the bodies of his prey in the empty caskets, Vengeance is Mine hits a pitch of Gothic Western fantasy that is equivalent to its predecessor. A major difference here, though, is the Civil War setting. Probably inspired by Leone’s use of the Civil War as a backdrop to The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, Vengeance is Mine quickly establishes itself as taking place in the South during the Civil War; riding into a ghost town, John is told that the town is empty because the fighting age men have left “to kill the Yankees.” This backdrop features its payoff when John attempts to claim a bounty for capturing Clint, only to be told that because the Confederates have lost the war, the state no longer exists officially, and therefore John won’t be paid. (The marshall’s response to the defeat of the Confederacy is to vow to drink all the whisky in town, so that none is left for the Yankees when they arrive.)  Interspersed throughout the narrative are flashbacks that show the relationship between John and Clint. John, it seems, was an accomplished horseman, with a beautiful girlfriend; Clint was ridden with jealousy. Clint’s father (Giovanni Di Bennedetto) favoured John, even though he wasn’t his biological son. This led Clint to shooting his father in the back, and then blaming John for the killing. John was arrested and convicted of the murder, and upon his release became a bounty hunter. Interspersed throughout the narrative are flashbacks that show the relationship between John and Clint. John, it seems, was an accomplished horseman, with a beautiful girlfriend; Clint was ridden with jealousy. Clint’s father (Giovanni Di Bennedetto) favoured John, even though he wasn’t his biological son. This led Clint to shooting his father in the back, and then blaming John for the killing. John was arrested and convicted of the murder, and upon his release became a bounty hunter.

In the present, John has a wife, Anne (Claudie Lange), and a son; John’s son is not his biological offspring but rather the child of Anne’s first husband, who abandoned Anne when the boy was two years old. Remembering his own past, John tells Anne that “One day he’ll [the child will] have to find out. It’s only right.” But John’s ties to Anne and her son seem to be driven more by duty than out of love. When John returns home after helping defeat Jurago to find his house razed to the ground and Anne’s son killed, he and Anne must travel with Clint to El Paso. Throughout the narrative, John and Clint circle one another. John is told of his mother’s recent death, and her wish that John find a way to forgive his half-brother: that if John and Clint were ever to face one another, John must not be “the one who shoots first.” Vengeance is Mine is, then, a Western about the burden of the past: “Even though we try to forget,” John says at one point, “the past is like an old wound.” The film sits alongside a number of other Italo-Westerns of the period that explore traumatic pasts and tortured family dynamics – often positioning close relations on opposite sides of the law. Included in this group are pictures such as Ferdinando Baldi’s Texas Addio (1966) and Il pistolero dell’Ave Maria (The Forgotten Pistolero, 1969). As a group, these films feel very much influenced by Anthony Mann’s American Westerns such as Winchester ’73 and The Man from Laramie. Anti-hippie sentiments were not exceptionally rare in Italian Westerns, which is probably to be expected given how political a number of the key filmmakers were; Alex Cox has suggested that Sergio Corbucci, for example, gave short shrift to hippie types because he perceived them as passive and lacking in any sense of engagement with social realities. In this film, Clint is depicted almost as a drifting hippie: a petulant youth, at one point he finds himself spending time with a group of Confederate drifters (presumably deserters), who with their womenfolk and families hide out, singing songs, in a group that has the appearance of a hippie commune. At the end of the film, John has been tortured and crucified upside down; his wife and adopted son have been killed. However, he manages to trap Clint’s crew in a ghost town and take them out one-by-one. This final sequence has an almost supernatural intensity, reminiscent of other Italo-Westerns which feature protagonists who may or may not have come back from the dead as vengeful ghosts – such as Antonio Margheriti’s E Dio disse a Caino… (And God Said to Cain, 1970) and Sergio Garrone’s Django il bastardo (Django the Bastard, 1969). (These are the films that find their Hollywood echo in Clint Eastwood’s High Plains Drifter [1973].) The High Gothic themes and intimations of supernatural vengeance are amplified by the use of a theremin on the soundtrack.  Joe... cercati un posto per morire! / Find a Place to Die (Giuliano Carnimeo, 1968) Joe... cercati un posto per morire! / Find a Place to Die (Giuliano Carnimeo, 1968)

There is some dispute over the authorship of Find a Place to Die, with some suggestion (not without evidence) that the picture was largely directed by its producer, the Argentine filmmaker Hugo Fregonese, rather than the credited director (Giuliano Carnimeo). This film was the only picture on which Fregonese, who had been directing features since 1945, was credited as producer; so the likelihood of Fregonese being involved with (or “overseeing”) the direction of the film is probably quite high. Find a Place to Die begins in the desert, with a shootout between husband and wife prospectors (Paul and Lisa Martin, played respectively by Piero Lulli and Pascale Petit), and a group of bandits led by Chato (Mario Darnell). When Paul is badly injured, Lisa decides to flee to a nearby village, where she seeks the assistance of a cynical gun-runner, Joe Collins (Jeffrey Hunter), in rescuing her husband. Joe is a disgraced former military man, hiding out from Texas Rangers after shooting “a bastard who was better off dead than alive.” With the promise of $2,000 in gold from Lisa for rescuing Paul, Joe assembles a motley crew, including Joe’s fellow gun-runner Gomez (Giovanni Pallavicino), treacherous gunslinger Paco (Reza Fazeli), sleazy “Reverend” Riley (Adolfo Lastretti), strongman Fernando (Giovanni Pazzafini) and his friend (and perhaps lover?) Bobo (Anthony Blod) – who is an expert locksmith/safecracker. Find a Place to Die is often dismissed as a “ho-hum” Italian Western that is very much in the American model – something that is emphasised by the basis of the film in the script for Henry Hathaway’s 1954 US Western Garden of Evil (which featured both Gary Cooper and Dicky Widmark in memorable roles) and the presence of Jeffrey Hunter in the lead role. (Hunter would tragically die a year after this film was released, at the age of 42, as a result of suffering an injury in an explosion staged for what would become his final film, Javier Seto’s Mafia drama Cry Chicago.) However, the picture makes distinctive use of some haunting locations, including what appears to be a derelict monastery. In fact, there’s distinctive use of ageing Mediterranean architecture throughout the picture.  Also notable is the film’s erotic sensibility, positioning both Pascale Petit and Daniela Giordano (as Juanita, the Lady Macbeth-like lover of doublecrossing gunfighter Paco) as objects of visual fetishism. Juanita’s flowing, white, feminine dress (she is introduced with bare legs, playing the guitar for the denizens of Eagle’s Nest) is in stark juxtaposition with the almost kinky cowboy garb (including tight-fitting leather trousers that would make Olivia Neutron-Bomb wince) worn by Lisa. (It’s difficult not to draw parallels between Lisa’s black leather and the fetishistic outfits worn by the muchachos in Giulio Questi’s Django Kill! or Dirk Bogarde’s black leather uniform in Roy Ward Baker’s The Singer Not the Song.) Strikingly, the film features a moment of nudity – stark for an Italian Western, though relatively tame by many other standards – in which a topless Juanita is caressed in bed by Paco; later, we see a nude Lisa bathing in a river, seemingly not cognisant of the sexual threat presented by the gang of miscreants Joe has managed to scrap up for the mission of rescuing Paul. (“My cloth shouldn’t stop me from being a man,” the creepy Riley asserts, “I have rights to the woman too, the same as everyone else.”) Sex and female sexuality were often present in Euro-Westerns, but rarely in such a forthright and demonstrably titillating manner. Also notable is the film’s erotic sensibility, positioning both Pascale Petit and Daniela Giordano (as Juanita, the Lady Macbeth-like lover of doublecrossing gunfighter Paco) as objects of visual fetishism. Juanita’s flowing, white, feminine dress (she is introduced with bare legs, playing the guitar for the denizens of Eagle’s Nest) is in stark juxtaposition with the almost kinky cowboy garb (including tight-fitting leather trousers that would make Olivia Neutron-Bomb wince) worn by Lisa. (It’s difficult not to draw parallels between Lisa’s black leather and the fetishistic outfits worn by the muchachos in Giulio Questi’s Django Kill! or Dirk Bogarde’s black leather uniform in Roy Ward Baker’s The Singer Not the Song.) Strikingly, the film features a moment of nudity – stark for an Italian Western, though relatively tame by many other standards – in which a topless Juanita is caressed in bed by Paco; later, we see a nude Lisa bathing in a river, seemingly not cognisant of the sexual threat presented by the gang of miscreants Joe has managed to scrap up for the mission of rescuing Paul. (“My cloth shouldn’t stop me from being a man,” the creepy Riley asserts, “I have rights to the woman too, the same as everyone else.”) Sex and female sexuality were often present in Euro-Westerns, but rarely in such a forthright and demonstrably titillating manner.

When he is first introduced, Joe is a despairing drunk, with a once promising career in the military behind him. (It’s tempting to read this autobiographically, given how Jeffrey Hunter’s once promising Hollywood career had been tarnished by the star’s battle with the booze.) The brutality of Chato’s gang is deftly established, Joe telling Lisa that Chato and his crew’s only entertainment is “torturing and killing.” That said, the crew Joe assembles to rescue Paul is little better. “There are only two things holding this pack of vermin together,” Joe warns Lisa: “You, and the gold. They’ve only left you in peace because you know the way [to the gold mine].” This, then, is a film of fragile allegiances, culminating in an extended, but expertly assembled, shootout at the Eagle’s Nest hideout. When Lisa tells Joe that she is “sorry [for causing] so much violence and greed,” Joe tells her that “Greed and madness were already in these men’s hearts before you came here.”  Mátalo! / Matalo! (Kill Him) (Cesare Canevari, 1970) Mátalo! / Matalo! (Kill Him) (Cesare Canevari, 1970)

An uncredited reworking of Tanio Boccia’s earlier Italo-Western Kill the Wicked! (Dio non paga il sabato, 1967), Cesare Canevari’s Matalo! is a headtrip of a film, easily sitting alongside roughly contemporaneous “acid” Westerns such as Peter Fonda’s The Hired Hand and Jodorowsky’s El Topo. Outlaw Burt (Corrado Pani; named Bart in the Italian language version) is heading to the noose. However, he is saved at the last minute by his gang: Mary (Claudio Gravy), Ted (Antonio Salines; Theo in the Italian version) and Phil (Luis Davila). Hiding out in a ghost town, the gang soon reveal their treacherous ways. Mary is Phil’s lover but is also having an affair with Burt; meanwhile Ted has eyes for Mary too. Knowing this, Mary isn’t above prick-teasing Ted in order to get her own way. The trio hold up a stagecoach, killing the soldiers guarding it and the innocent civilians travelling in it. Burt is wounded and betrayed by the others, who leave him for dead. However, unbeknownst to Ted and Phil, Burt is still alive; under the cover of night, he converses with Mary, and the two plot Burt’s revenge on the deceitful dudes who betrayed him. Into this madness ride Bridget (Ana Maria Mendoza), a woman in search of her husband and son, murdered by Burt’s gang when they robbed the stagecoach, and a stranger – a drifter named Ray (Lou Castel), who doesn’t carry a gun but is instead armed with a brace of boomerangs(!!!!) Taken captive by Phil, Ted and Mary, Ray and Bridget eventually seize their opportunity to enact revenge. Matalo! opens with a prog rock-style score under documentary-like shots of a Western town, including glimpses of children playing. The verite-like nature of these shots, and the incorporation of children into the frame, recalls the opening of Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch, released a year earlier, and the manner in which it establishes the town of Starbuck before it is ripped apart by the violence of both the titular Bunch and Robert Ryan’s band of bounty hunters. The parallels with The Wild Bunch find their payoff moments later, when Burt’s own bad bunch shoot up the town in order to save their compadre from the noose.  The film’s trippy tone is foregrounded in this sequence with the introduction of Burt, filmed as he is directed to the noose and flanked by lawmen, and intercut with tight closeups of the eyes of Mary, hidden behind a black veil. Images drift in and out of focus, and everything erupts into brutal violence, Burt’s crew leaving a trail of corpses in their wake. No dialogue is spoken in these first 10 minutes. Elsewhere, the film employs almost subliminal cutaways at various points, and a disorienting 360 degree rotation by the camera at the climax. The whole aesthetic of the picture verges on the experimental, seeming to borrow from both European New Wave cinemas and the techniques of Hollywood Renaissance filmmakers such as Arthur Penn and Peckinpah. The film’s trippy tone is foregrounded in this sequence with the introduction of Burt, filmed as he is directed to the noose and flanked by lawmen, and intercut with tight closeups of the eyes of Mary, hidden behind a black veil. Images drift in and out of focus, and everything erupts into brutal violence, Burt’s crew leaving a trail of corpses in their wake. No dialogue is spoken in these first 10 minutes. Elsewhere, the film employs almost subliminal cutaways at various points, and a disorienting 360 degree rotation by the camera at the climax. The whole aesthetic of the picture verges on the experimental, seeming to borrow from both European New Wave cinemas and the techniques of Hollywood Renaissance filmmakers such as Arthur Penn and Peckinpah.

Burt lives by a code, taught to him by his father: “Money is love, love is possession, possession is life. Life is a robbery.” The parallelism here is reminiscent of Tony Montana’s code in Brian DePalma’s later Scarface (“This country, you gotta make the money first. Then when you get the money, you get the power. Then when you get the power, you get the women”). For much of its running time, Matalo! is a picture that features bad people doing bad things. Burt and his gang aren’t nuanced anti-heroes; they are simply nasty, amoral shits. They drift like hippies and dress in a vaguely counter-cultural way, and it’s difficult not to see some similarities between Burt, Ted, Mary and Phil, and Charles Manson’s drifting, murderous “Family.” Robbing the stagecoach, Phil orders the execution of a father in front of his adolescent son. Later, they stage a brutal home invasion, when they discover that the ghost town has a single occupant: the widow Constance Benson (Mirella Pamphili), whose family once ruled over the town. This is the Italo-Western as a feverish, trippy nightmare, punctuated by moments of fetishistic action: Mary turning the tables on Ted and kinkily ruling over him; Lou Castel’s Ray being chainwhipped in the town square.

Video

Each of the films is housed on its own Blu-ray disc. Each disc presents the viewer with the option of watching the film in its “Italian Version” or “English Version.” Selecting the former automatically selects the Italian language track and English subtitles, along with Italian language onscreen credits, etc; selecting the latter automatically selects the English language audio track, with English language onscreen credits. $10,000 Blood Money runs for 97:25 mins and takes up slightly under 30Gb of space on its disc. Vengeance Is Mine has a running time of 95:20 mins and fills just under 28Gb of space on its disc. Find a Place to Die runs for 89:05 mins and takes up approximately 28Gb of space on its disc. Finally, Matalo! has a running time of 95:15 mins and fills slightly over 25Gb of space on its disc. All of the films are apparently uncut. It should be noted that ANICA (the Associazione Nazionale Industrie Cinematografiche Audiovisive) lists a longer running time for Matalo! (of 101 mins) but it’s unclear whether this version still exists or was ever released commercially. All four films were shot on 35mm colour stock. $10,000 Blood Money / 10,000 Dollars for a Massacre and Vengeance is Mine were shot in 2-perf widescreen formats, and are presented on their discs in the 2.35:1 aspect ratio. Find a Place to Die and Matalo! were shot “flat,” and are presented on their discs in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio. All four pictures have been restored in 2k; these restorations are based on each film’s original negative. The presentations of all four films are superb. An excellent level of fine detail is present in all of the films. (I’d suggest that it’s now possible to count every bead of sweat on the brows of the actors in Find a Place to Die.) Some very minor damage is present in a few instances: there are a few scenes in $10,000 Blood Money and Vengeance is Mine, for example, where some density fluctuation in the emulsions of the negatives seems to be apparent. There re minor flecks and specks, indicative of debris on the negative, in Matalo! However, none of this is detrimental to one’s enjoyment of the presentations, however. Colours are fine and consistent throughout all of the presentations. Contrast levels are very pleasing, with rich and deep blacks tapering into well-defined midtones and balanced highlights. (In fact, for the two films shot in 2-perf widescreen – formats which would have had to go through several generations before a cinema print could be made – the fact that Arrow’s restorations are based on the respective camera negatives means that contrast levels in these HD digital presentations will most likely be more defined than in original 35mm cinema prints.) The encodes are all very solid, with organic 35mm film grain preserved and no harmful digital artefacts being introduced into the presentations. 10000 Dollars for a Massacre

Vengeance is Mine

Find a Place to Die

Matalo!

NB. Some full-sized screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

All four films are presented with the option of an Italian LPCM 1.0 track (with optional English subtitles translating the Italian dialogue) or an English LPCM 1.0 track (with optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing). The tracks for all four films are pleasing, with a strong sense of depth and range. Vengeance is Mine contains an onscreen title highlighting any differences in pitch between the two tracks as being “per the original soundtrack negative and not a fault of this release.” (Any differences are only really noticeable when one compares the two tracks directly.) On the English track for this film, the music is a little “muddy” during the opening sequence but quickly settles into something much more crisp and deep. While perfectly serviceable, it’s worth noting that Find a Place to Die’s English track has some slight “wobble” and feels a little murky, with less range, in comparison with the crisp and clean Italian track on the same disc. The English and Italian tracks on Matalo! are equivalent; here it’s worth noting that the high notes on the film’s whistled theme feel slightly “clipped,” but this seems to be down to the recording of the score itself rather than reflective of the qualities of the audio tracks on this disc. All four films, in sum, feature very satisfying audio options, and whether one chooses to watch these films in Italian or English will depend on the viewer’s preference for one language or the other when watching Italo-Westerns.

Extras

DISC ONE: -  10,000 Dollars for a Massacre (97:25). 10,000 Dollars for a Massacre (97:25).

- Commentary by Lee Broughton. Academic Lee Broughton offers an enthusiastic commentary for the film, highlighting aspects of the narrative and exploring the film’s relationship with the paradigms of the Italo-Westerns of the period. Broughton talks about the industrial context, exploring Italian cinema’s dedication to the filone principle, and the evolution of the Italo-Western during the 1960s. - “A Shaman in the West” (10:05). Fabio Melelli, an Italian journalist, offers some thoughts about 10,000 Dollars for a Massacre. Melelli considers the film’s relationship with Corbucci’s Django and reflects on the shared casting of Loredana Nusciak in both pictures. He talks about Gianni Garko’s Django and the qualities that mark this character as different from the Django played by Franco Nero in the Corbucci picture. Italian, with optional English subtitles. - “Tears of Django” (21:58). This is described as a “newly edited featurette” that consists of interviews with Gianni Garko and director Romolo Guerrieri. Guerrieri talks about how he progressed from being a dependable assistant director to making his own films; and he talks about his memories of shooting 10,000 Dollars for a Massacre. He discusses the casting of Garko and Camaso. Garko reflects on how he approached playing Django in this film, and considers his work in the genre of Italian Westerns. Italian, with optional English subtitles. Please note that there seems to be an error on this disc, in which the English subtitles “disappear” at around 9 minutes into this featurette. - “The Producer Who Didn’t Like Western Movies” (14:18). Producer Mino Loy is interviewed. He opens by stating that he never liked Westerns, aside from a few of the American classics, but was swept along by the popularity of Euro-Westerns during the late 1960s. Loy talks about the Anglicising of the names of the cast and crew of Italo-Western films, and how they were marketed as “B” features in the hope they would be confused with American product. Loy also discusses Corbucci’s Django, which he admits to not remembering particularly well, and engages with how the popularity of Django led to so many imitators. Italian, with optional English subtitles. - “How the West Was Won” (19:21). Writer Ernesto Gastaldi reflects on his role in the making of 10,000 Dollars for a Massacre. Gastaldi says that in his script, the protagonist wasn’t called “Django”: this was added later. He talks a little about Claudio Camaso and his reputation for being “hot-headed” and “prone to violence.” He also talks about Luciano Martino and his input. The script, Gastaldi says, was inspired by Richard Brooks’ The Professionals (1966). Italian, with optional English subtitles. - Italian Trailer (3:26). - Image Gallery (23 images). DISC TWO: -  Vengeance Is Mine (95:20). Vengeance Is Mine (95:20).

- Commentary by Adrian J Smith and David Flint. Flint and Smith provide a warm commentary for the film, highlighting its association with the Gothic paradigm. They talk about the cast and crew, exploring Gianni Garko’s career in particular, and reflect on the boom in production of Italo-Westerns and how Italian Westerns became increasingly focused on comedy in the early-1970s. - “Crime and Punishment” (13:05). Journalist Fabio Melelli offers a new introduction to Vengeance is Mine, highlighting its similarities and differences from 10,000 Dollars for a Massacre, which he suggests is rooted in the more auteurist approach of director Giovanni Fago. Melelli suggests that Claudio Camaso’s performance was an attempt to “channel” his brother Gian Maria Volonte’s role as Indio in Leone’s For a Few Dollars More. Melelli spends some time talking about Camaso’s colourful life: his youthful association with far-right activists, his relationships with women, and his conviction for killing an acquaintance in the film industry, Vincenzo Mazza. Italian, with optional English subtitles. - “Cain and Abel” (25:03). Gianni Garko and writer Ernesto Gastaldi speak, separately, about their work on this film. Gastaldi discusses the craze for making Italo-Westerns, and how he was approached by Luciano Martino to write Arizona Colt, leading to his work on Leone’s Nobody films. Gastaldi also talks about the creation of the Sartana character, and how this led to a plethora of films that featured Sartana. For Gastaldi, it was important to make Italian Westerns different from American Westerns, but ultimately, he says, they are “fables, or classical tragedies.” He admits that he found writing Westerns more fun than writing, say, horror movies. Discussing Vengeance Is Mine, Gastaldi discusses how he was asked by Luciano Martino to write the script, based on a title that had already been set in stone. The premise of the two brothers on opposite sides of the law was established by one of Luciano Martino’s office staff, and this developed into the script. Gastaldi also discusses the work of the director, suggesting that the first half of the film – which plays with memory and uses flashbacks – is stronger than the second half, which he implies is more conventional in its use of Western motifs. These are archival interviews that have been newly edited for this release. Italian, with optional English subtitles. - “In Conversation with Nora Orlandi” (15:34). Composer Nora Orlandi discusses her work in film scoring. This is an archival interview that has been newly edited for this release. Italian, with optional English subtitles. - “Movie After Movie” (16:42). The film’s producer, Mino Loy, speaks about his career in cinema, which progressed from his love of photography. Loy talks about his beginnings as a maker of documentaries, the production of which was supported by healthy government subsidies. From here, Loy progressed to making commercial feature films and collaborating with Luciano Martino. He discusses in some detail how Italian commercial films of that period would attract financing and acquire distribution. Italian, with optional English subtitles. - Italian Trailer (3:14). - Image Gallery (24 images). DISC THREE: -  Find a Place to Die (89:05). Find a Place to Die (89:05).

- Commentary by Howard Hughes. Howard Hughes, who has written extensively about the Italian Western, offers a commentary for Find a Place to Die. He discusses the authorship of the film, engaging with the claims that have been made that the film was actually directed by its producer, Hugo Fregonese. Hughes also talks about the cast, and he reflects on how the Italian Westerns extended some of the narrative paradigms of the pepla that preceded them. - “Venus and the Cowboys” (11:45). Journalist Fabio Melelli provides an introduction to Find a Place to Die. He talks about Pascale Petit and Danielo Giordano’s claims that producer Hugo Fregonese actually directed the film, rather than Giuliano Carnimeo. Melelli suggests that the aesthetic of the film supports these claims. He also talks about the locations used in the production of the picture. Italian, with optional English subtitles. - “Sons of Leone” (18:10). Director Giuliano Carnimeo discusses his career in cinema. He reflects on the popularity of the Sartana series with which Carnimeo is indelibly associated. He talks about Garko’s screen presence, describing the actor as “meticulous” in his methodology. This is an archival interview that has been newly edited for this release. Italian, with optional English subtitles. - “Traditional Figure” (31:17). Musician and soundtrack afficionado Lovely Jon talks about the work of Gianni Ferrio, the composer of the score for Find a Place to Die. Lovely Jon compares Ferrio to the American soundtrack composer Lalo Schifrin, and reflects on Ferrio’s approach to film scoring in multiple genres. - Image Gallery (37 images). DISC FOUR: -  Matalo! (94:15). Matalo! (94:15).

- Commentary by Troy Howarth and Nathaniel Thompson. American critics Howarth and Thompson offer an enthusiastic commentary for Matalo! They explore its place within the Euro-Western canon, and examine its context in terms of director Canevari’s body of work. They also highlight Matalo!’s echoes of the post-Manson Family death of the countercultural dream, and consider the near-experimental approach that Canevari takes to bringing the story to the screen. - “The Movie That Lived Twice” (16:09). Journalist Fabio Melelli delivers an introduction to Matalo! Melelli highlights the film’s reworking of the narrative of Tanio Boccia’s Kill the Wicked! (1967). Melelli talks about Canevari’s major addition to the story: the boomerang-wielding stranger played by Lou Castel. (Boccia’s film features instead a gunslinger without a gun.) Melelli also talks about Canevari’s experimental approach to filming and editing Matalo! Italian, with optional English subtitles. - “A Milanese Story” (44:42). Italian film critic Davide Pulici talks about the work of Cesare Canevari, whom Pulici knew personally. Pulici reflects on Canevari’s early career as an actor, and his passion for French cinema; Pulici suggests that as a director, Canevari’s filmic reference points were largely from French cinema rather than Italian films. Pulici also discusses Canevari’s connection to Milan, where the majority of his films as a director were made. Italian, with optional English subtitles. - “Untold Icon” (39:28). Soundtrack enthusiast Lovely Jon talks about the work of Matalo!’s soundtrack composer, Mario Migliardi. Lovely Jon describes Migliardi’s work as “very forward-thinking,” highlighting the composer’s use of the organ in his manifold film scores. - Italian Trailer (3:32). - Image Gallery (16 images).

Overall

Arrow’s Blood Money set is excellent. The four films are relatively diverse, though there is an obvious relationship between $10,000 Blood Money and Vengeance is Mine, in terms of shared cast and crew. Both of those films are Westerns in the tortured Gothic vein, whilst Find a Place to Die is a much more conventional Western in an American style. On the other hand, Matalo! is probably best described as an “acid” Western. Certainly, the latter two films have some rabid fans and also some equally rabid detractors. In truth, all of the pictures in this set are worth watching, and the more westerns all’italiana that hit HD home video formats (and get this amount of loving care and attention from their distributors), the better. Arrow’s presentations of all four films are excellent; the inclusion of Italian and English language tracks is par for the course with Arrow, but is to be applauded. All four movies are also supported by some superb contextual material, including some new content (such as audio commentaries) and some pre-existing material (including re-edited interviews with participants). It’s an excellent set, and well worth the investment for any fan of westerns all’italiana. $10,000 Blood Money / 10,000 Dollars for a Massacre

Find a Place to Die

Matalo!

Vengeance is Mine

|

|||||

|