|

|

Calcutta (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (19th December 2023). |

|

The Film

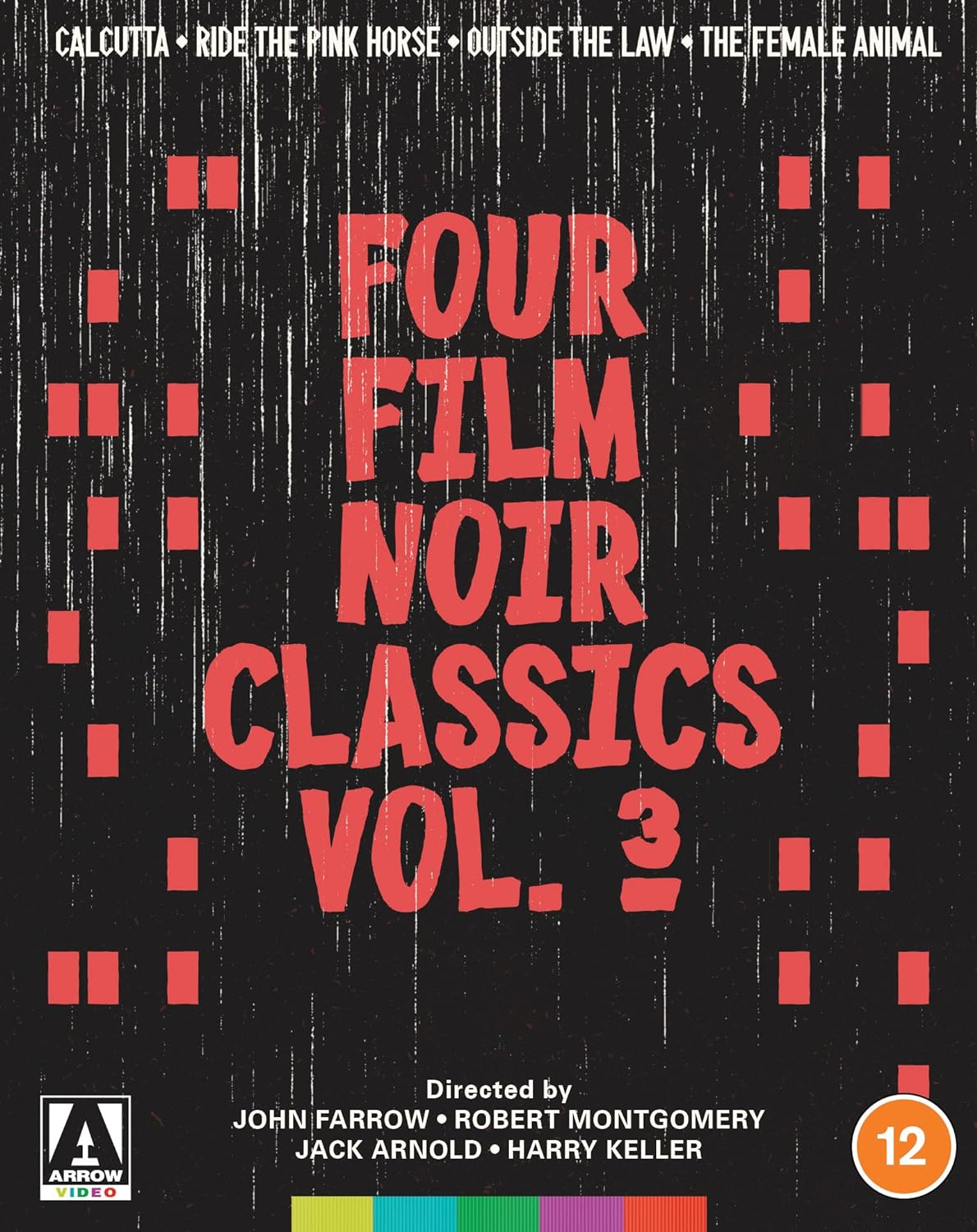

Four Film Noir Classics Volume 3 Arrow have released a second set of films noirs on Blu-ray. Titled Four Film Noir Classics, Volume 3, Arrow’s new boxset contains the following pictures: John Farrow’s 1946 film Calcutta, starring Alan Ladd, William Bendix, and Gail Russell; the 1947 adaptation of Dorothy B Hughes’ novel Ride the Pink Horse, directed by and starring Robert Montgomery; Jack Arnold’s 1956 picture Outside the Law; and Harry Keller’s 1958 film The Female Animal, the final picture to star Hedy Lamarr.  Set immediately after the Second World War, Calcutta features Alan Ladd playing pilot Neale Gordon, who with his co-pilot Pedro (William Bendix) flies cargo on the route between Calcutta and Chungking. Neale and Pedro are informed of the violent death of their friend, fellow pilot Bill Cunningham (John Whitney). Deciding to investigate, Neale and Pedro confront Bill’s fiancée, Virginia (Gail Russell), and become aware of an illicit trade in precious gems that involves nightclub owner Eric Lasser (Lowell Gilmore), merchant Malik (Paul Singh), and possibly also Virginia. Determined to get to the bottom of Bill’s murder and ensure his killer/s face/s justice, Neale and Pedro’s quest becomes complicated further when Malik is killed and Pedro is framed for the crime. Set immediately after the Second World War, Calcutta features Alan Ladd playing pilot Neale Gordon, who with his co-pilot Pedro (William Bendix) flies cargo on the route between Calcutta and Chungking. Neale and Pedro are informed of the violent death of their friend, fellow pilot Bill Cunningham (John Whitney). Deciding to investigate, Neale and Pedro confront Bill’s fiancée, Virginia (Gail Russell), and become aware of an illicit trade in precious gems that involves nightclub owner Eric Lasser (Lowell Gilmore), merchant Malik (Paul Singh), and possibly also Virginia. Determined to get to the bottom of Bill’s murder and ensure his killer/s face/s justice, Neale and Pedro’s quest becomes complicated further when Malik is killed and Pedro is framed for the crime.

Calcutta is very much a film of the post-war landscape, with all the baggage that ensues from this. Men operate in a homosocial field, seeking the company of other men; women represent a threat to the equilibrium of the stability offered by masculine cameraderie. In the film’s opening sequence, Neale and Pedro are assisted by Bill, who tells his friends that he is planning to get married. Neale responds by warning Bill that his fiancée will want him to give his career up for something more stable, and that’ll “bust us up.” Later, Neale admits that he’s suspicious of Virginia (or “Ginny”), because he simply “suspect[s] anybody that had anything to do with him [Bill] that I didn’t know about.” Marriage, Neale rants to Bill’s fiancée, is “like grounding a DC [Douglas Commercial airplane] and letting him rust.” “You’re cold, sadistic, egotistical,” Ginny accuses. “Maybe, but I’m still alive,” Neale snarls back at her. Investigating the death of Bill, who Neale and Pedro are told was strangled with “one of those Thuggee nooses,” Neale seeks the assistance of Marina (June Duprez), a nightclub singer. It’s clear that Marina has eyes for Neale, and the pair may have been involved with one another at some point, but Neale certainly ain’t the “settling down” type. He’s too busy doing what a man’s gotta do. Neale’s outward contempt for both Ginny and conventional marriage (and his apparent disinterest in settling down with women such as Marina, more generally), along with his closeness to his deceased friend, have led some critics to suggest that Neale and Bill’s relationship may have had a quietly (closeted) romantic dimension. Certainly, Calcutta is a film that plays with gender norms, featuring an excellent secondary performance from Edith King as the cigar smoking jeweller Mrs Smith, for example. Calcutta is ultimately very much a studio-based film noir and a star vehicle for Ladd. The narrative is derivative of a number of other contemporaneous films – particularly, in its exotic settings, Casablanca. (The film is chiefly set in Calcutta, prior to Indian independence and therefore populated by British police, but also briefly Chungking.) The film’s depiction of non-Anglo cultures is perhaps strikingly “unenlightened,” and there’s a definite sense in which the film may attract accusations of association the exotic locales (and their folk) with deceit, treachery, and mortal danger. (That said, many contemporaneous “home” set American films noirs depicted US urban spaces in a similar manner.) However, the whole thing is so well-made, with some great secondary performances (William Bendix’s turn as Pedro Blake is particularly memorable), that it’s difficult to care all too much. There’s typical hardboiled tough talk aplenty, a strong sense of conspiracy and fatalism, and noir’s classic juxtaposition of the “pure” girl (Marina) with the potential femme fatale (Ginny). The climax is arguably a little too rushed, the film racing to its denouement in the final moments, but Calcutta serves up an enjoyable – albeit not exceptionally memorable – feast of post-war noir treats. As Neale says at one point, “Does a guy have to trust a girl to fall for her?”  Robert Montgomery’s Ride the Pink Horse is adapted from the novel by Dorothy B Hughes, though takes some significant liberties with its source material. (The same could be said of that other great Hughes adaptation, Nicholas Ray’s In a Lonely Place.) The film focuses on “Lucky” Gagin (Robert Montgomery), who arrives in the New Mexico town of San Pablo with the intention of blackmailing hoodlum Frank Hugo (Fred Clark) in retaliation for the murder of Lucky’s friend, Shorty Thompson. Robert Montgomery’s Ride the Pink Horse is adapted from the novel by Dorothy B Hughes, though takes some significant liberties with its source material. (The same could be said of that other great Hughes adaptation, Nicholas Ray’s In a Lonely Place.) The film focuses on “Lucky” Gagin (Robert Montgomery), who arrives in the New Mexico town of San Pablo with the intention of blackmailing hoodlum Frank Hugo (Fred Clark) in retaliation for the murder of Lucky’s friend, Shorty Thompson.

Set against Hugo’s syndicate, Lucky receives some unanticipated help from carousel operator Pancho (Thomas Gomez; the titular “pink horse” appears to be one of the horses on Pancho’s carousel) and a young local woman, Pila (Wanda Hendrix). He also falls into the orbit of FBI agent Bill Retz (Art Smith), who appears to be building a dossier on Hugo and his syndicate. Like many films noirs of the immediate post-war period, Ride the Pink Horse features a protagonist who has returned from the war, suffering what would today be termed PTSD. “You’re not a bad fella,” Retz tells Lucky, “Like the rest of ‘em, all russed up because you fought a war for three years and got nothing out of it but a dangle of ribbons.” Aloof and outwardly “cold,” Lucky is established early in the film as something of a bigot, treating the Spanish-speaking locals with thinly-veiled contempt upon his arrival in the small New Mexico town. However, as the narrative unfolds the character develops a firm friendship with both local girl Pila and carousel operator Pancho, suggesting that Lucky’s apparent bigotry is perhaps little more than a defensive reflex. Lucky likes Pila because she isn’t a “dame” (ie, a woman “spoiled” by privilege and vanity): talking about Hugo’s moll, Marjorie (Andrea King) – who is most certainly a “dame” – Lucky tells Pila, “Understand what a human being is? Well, they’re [‘dames’ are] not human beings. They’re dead fish with a lot of perfume on ‘em. You touch ‘em, and you always get stung. You always lose.” Ride the Pink Horse benefits from a macho performance from its director-star, and some exceptional terse, clipped dialogue. “Look, copper, don’t wave any flags at me,” Lucky spits at Retz during one exchange, “I seen enough flags. They don’t register anymore.” In Frank Hugo, the hearing aid-wearing leader of the gang of hoodlums, the film also has an excellent, profoundly memorable villain. (It’s clear that Fred Clark relishes playing this part.) Lucky clearly displays contempt for Hugo, who because of his hearing problems didn’t serve in the war but nevertheless tries to establish some kind of slimy camaraderie with Lucky, suggesting that the two are alike: “There are two kinds of people in the world,” Hugo tells Lucky, “Ones who fiddle around, worrying whether a thing is right or wrong; and guys like us.” Lucky, however, is having none of it. Ride the Pink Horse is arguably the standout film in this collection. With the vibe of an independent picture, this was clearly a passion project for Montgomery, even though it deviates quite substantially from the (excellent) source novel by Dorothy B Hughes. (To be fair, though, as noted above Nicholas Ray’s highly-regarded In a Lonely Place plays fast and loose with the source material too; Hughes’ work is excellent territory for a film noir, but it seems both Ray and Montgomery knew that in order to adapted her worldview for the big screen, substantial changes needed to be made to the basic narrative of each story.) Montgomery’s Ride the Pink Horse is fierce, nightmarish, and feverish. The protagonist, Lucky, is outwardly racist, violent, and uncouth; a veteran of the Second World War, he clearly suffers from combat fatigue. As the narrative progresses, we realise that Lucky’s apparent racism is one of many reflexes designed to obscure his vulnerable core self; he makes friends with Pancho and Pila, siding with them against Hugo and Retz. Pancho, Pila, and Lucky’s shared status as underdogs pits them against Retz and Hugo, figures of the establishment. In some ways, the film is reminiscent of the later Zapata Westerns – films in which an Anglo protagonist journeys into Latin America and experiences a humanistic/political/existential awakening.  Jack Arnold’s Outside the Law begins in post-war Berlin, where a US soldier, Craven (Stuart Wade), is shot and killed in a counterfeiting deal gone bad. Back in the States, Craven’s friend Johnny Salvo (Ray Danton) returns home. A decorated soldier, Salvo is also a convict and due to be returned to San Quentin prison now that his tour of duty has ended. The Treasury asks Salvo to help them round up the other counterfeiters, in exchange for a full pardon. Jack Arnold’s Outside the Law begins in post-war Berlin, where a US soldier, Craven (Stuart Wade), is shot and killed in a counterfeiting deal gone bad. Back in the States, Craven’s friend Johnny Salvo (Ray Danton) returns home. A decorated soldier, Salvo is also a convict and due to be returned to San Quentin prison now that his tour of duty has ended. The Treasury asks Salvo to help them round up the other counterfeiters, in exchange for a full pardon.

In charge of the investigation is chief agent Alec Conrad (Onslow Stevens), Johnny’s father. Conrad put his own son in prison after Johnny accidentally killed an elderly woman whilst driving under the influence of alcohol; subsequently, Johnny changed his surname to reflect his broken relationship with his father. A series of counterfeit bills provide the investigators with a lead in the case, and Johnny is required to approach Craven’s widow, Maria (Leigh Snowden), in order to find out what she knows about the counterfeiting ring. Johnny soon becomes involved romantically with Maria, but faces competition in Don Kastner (Grant Williams), who presents himself as a family friend but is much more than this. Johnny’s investigation into the counterfeiting ring eventually leads him to suspect Don and Maria’s boss, Mr Bormann (Raymond Bailey). At the heart of the film are a number of relationships between men: Conrad’s relationship with his son, Johnny, has been rendered fragile (if not completely broken) by Conrad ensuring that Johnny faced justice for the manslaughter of the elderly woman he hit with his car. For his part, Conrad regrets not being present during Johnny’s youth: at that point in his life, Conrad was a workaholic, alienated from his family. It is clear that Conrad sees the investigation, and the involvement of Johnny within it, as a means of trying to heal his relationship with his son. “He’s got a chip on his shoulder the size of the world,” Conrad tells a colleague whilst discussing his son, “All I want to do is set things right.” During the investigation, Johnny also develops a strong friendship with fellow war veteran and Secret Service Agent Phil Schwartz (Jack Kruschen). Both men are struggling to adapt to civilian life back home after their experiences in the European field of conflict. It seems evident from Johnny’s first meeting with Maria that the pair will fall in love, and it is equally evident from Johnny’s first encounter with Don that not only is Don “competition” for Maria’s affections but also involved in the counterfeiting ring. In this sense, the film’s plot has little mystery or suspense. At one point, Don has Johnny badly beaten in his hotel room, leading Conrad to express regret over involving his son in the investigation: “I wanted to see you again,” Conrad tells Johnny, his love for his son breaking through his macho façade for a few moments, “to try to make up for things, but I didn’t want you to get hurt.” Conrad tries to cut Johnny loose from the investigation, on the proviso that Johnny stays in touch with his father; but Johnny, a man of strong personal ethics, wants to see the job through – regardless of the threat to his personal safety. Outside the Law is a fairly by-the-numbers story of returning veterans, counterfeiting, and Treasury agents – with criminals (Don and Bormann) masquerading as “legitimate” businessmen, prefiguring the depiction of the “corporate” underworld in later films such as John Boorman’s Point Blank. Bubbling beneath this is Johnny’s redemption. There is no femme fatale here; in place of that noir trope is a love rivalry, and within the narrative crime plays second fiddle to a theme of sexual jealousy – between Johnny and Don, over the widow Maria Craven. The story is told from a variety of perspectives, mostly focalised through Johnny but at times sharing the points-of-view of, variously, Alex, Maria, and Don. The climax is admittedly hurried but features a shootout that is made memorable by its unusual setting – a deserted bus depot.  Harry Keller’s The Female Animal takes place in Hollywood, and opens with booze-soddled actress Vanessa Windsor (Hedy Lamarr) experiencing a blackout on a film set after seeing a man, Chris Farley (George Nader), with another woman. The rest of the film is told in extended flashback, and we see the first meeting between Vanessa and Chris – on the set of another film, where Chris saved Vanessa’s life by pushing her out of the way of a falling lighting rig. Harry Keller’s The Female Animal takes place in Hollywood, and opens with booze-soddled actress Vanessa Windsor (Hedy Lamarr) experiencing a blackout on a film set after seeing a man, Chris Farley (George Nader), with another woman. The rest of the film is told in extended flashback, and we see the first meeting between Vanessa and Chris – on the set of another film, where Chris saved Vanessa’s life by pushing her out of the way of a falling lighting rig.

Vanessa soon becomes besotted with the younger Chris, and eventually cajoles him into a relationship, allowing him to stay at her beach house (which she nicknames “Windsor Castle”). Soon, Chris comes to tire of being a “kept man” and desires a way out of his relationship with Vanessa. Conversation between the two sometimes focuses on Vanessa’s wayward daughter Penny (Jane Powell), though for a time Chris and Penny never meet – until, that is, Chris unknowingly saves the sozzled Penny from her abusive boyfriend, “Piggy” (Gregg Palmer). Chris gives Penny a ride home, but she clumsily attempts to seduce the stranger. Chris deflects her, simply because Penny is still in high school; at this point, he is unaware that Penny is the daughter of his lover. Eventually, Vanessa tries to pressure Chris into marrying her, suggesting a wedding would “be wonderful for your career. There’ll be acres of publicity.” However, Chris departs, leaving a “Dear John” letter for his lover and reasoning that in a marriage to Vanessa, he’d “be a legalised gigolo.” Penny declares her love for Chris, and Vanessa descends into the bottle – leading to the incident depicted in the film’s opening sequence. (The woman whose presence on Chris’ arm leads to Vanessa’s blackout is revealed to be Penny.) Vanessa and Penny have a fractious relationship. Vanessa worked her way up from the gutter, and sees her daughter as spoilt and ungrateful for the privileges from which she has so obviously benefitted. Vanessa is drawn to Chris partly because of his own modest, unpretentious background: visiting his home, she finds that it reminds her of earlier times. “I used to live in a place just like this,” she tells him, and Chris is startled as she adds, “That is, when I could afford to pay the rent.” For his part, Chris quickly begins to tire of the imbalance within his relationship with Vanessa. When she sends Chris a bundle of expensive clothes, he fires back: “What kind of guy do you think I am, taking 1800 dollars of clothes from a woman? If I took them, I’d be a tramp.” Meanwhile, Vanessa is given advice – by another “over the hill” actress named Lilly Frayne (Jan Sterling), who keeps a gigolo named Pepe (Richard Avonde) in tow – about how to keep Chris in check: “Never let them have a career. Keep them sharecropping. That’s the idea.” Despite the tension between them, Vanessa and Penny have much in common: both are sexually forthright, taking active roles in seducing men; and both have a clear problem with the booze. The apple, it seems, never falls far from the tree. Elsewhere, the film’s askance view of sexual politics bubbles to the surface in a scene in which Chris is verbally admonished by Penny (who tells him he Is “just one of a long line” of men that her mother has “picked up and dropped”) and responds by slapping and spanking her – with the intention of calming her down(!!!) The Female Animal is a Hollywood-set film noir, much like Robert Aldrich’s The Big Knife and Billy Wilder’s Sunset Blvd.; in particular, Chris and Vanessa’s relationship was so obviously written to mimic the affair between William Holden and Gloria Swanson’s characters in the Wilder picture. Much of The Female Animal is presented through a female point-of-view (that of Vanessa), and Vanessa’s toxic relationship with her challenging daughter has some echoes of Mildred Pierce. The whole thing builds to a final coda which is possibly the best thing about the picture; without wishing to spoil the film, this final scene has something of the ambiguity of the great denouement of Michael Curtiz’s Angels with Dirty Faces. It’s tempting to write more about this, but I’ll leave it there… This was Hedy Lamarr’s last film; and goddammit, she gives the role her all. However, it’s difficult not to think that this one was easily outclassed, at least in the noir stakes, by its “B” feature… which was none other than Orson Welles’ incredible Touch of Evil.

Video

Each of the films is included on its own disc. All of the films are presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec. Each of the films is included on its own disc. All of the films are presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec.

Calcutta is presented in its original aspect ratio (1.33:1) and with a running time of 83:17 mins. The 35mm monochrome photography is captured excellently, with a very strong level of fine detail present throughout the film and nicely-balanced contrast levels. Highlights are even and balanced, and blacks are rich and deep. Midtones are richly defined too. There is some small evidence of damage throughout the film – mostly limited to pesky vertical scratches – but these “flaws” are wholly organic and never distracting. The encode to disc is sold, and ensures the presentation retains the grain structure of 35mm film. Ride the Pink Horse is also presented in 1.33:1 and, photographed on 35mm monochrome stock, has an equally pleasing presentation on its disc. The film runs for 101:20 mins. Fine detail is evident throughout, and midtones on this one are particularly well-defined, with balanced and even curves into both the toe and shoulder. There is no print damage worth mentioning here – certainly there is far less evidence of print damage than Calcutta. Again, a solid encode ensures the presentation remains filmlike in terms of its structure. Photographed in the next decade, Outside the Law is presented in the newer 1.78:1 ratio. The 35mm monochrome photography on this one benefits from the TV-like studio lighting used in much of the film, with the film stock not being pushed to the same limits as the stock in the two earlier films. The film runs for 81:18 mins. Thanks to the studio lighting and the qualities of 50s film stocks (in comparison with those of the 1940s), this presentation is particularly crisp (and, dare I say it, “slick”), with an excellent level of fine detail present throughout. Again, midtones are richly defined and highlights and shadows also balanced and rich. There are some very fleeting white blemishes and scratches in a few scenes, suggesting debris and very, very slight damage to the negative. Another strong encode to disc preserves the film’s grain structure and results in a pleasingly filmlike experience. On the final disc, The Female Animal presents this set’s only ‘scope experience. The Female Animal was shot in Cinemascope, and here is presented in the 2.35:1 ratio. Again, it was shot on 35mm and in monochrome. The presentation is crisp. (I’m running out of adjectives here; the presentations of all four films are pleasingly solid.) There is some very small damage in the form of white flecks that appear in a handful of scenes, and about an hour into the film there is some apparent evidence of density fluctuations in the film’s emulsions. This is very fleeting, however. Contrast levels are once again very good, with defined midtones and balanced highlights and shadows. Another excellent encode ensures the presentation is filmlike in terms of its structure. The film’s running time is 82:20 mins. NB. Some full-sized screengrabs from each of the films are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

All four films are presented with LPCM 1.0 tracks and optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. These tracks are all very good, and demonstrate excellent range and clarity. The differences between them, negligible though they are, may be credited to advancements in sound recording methods and technology from the 1940s to the late 1950s. Subtitles are easy to read throughout and free from errors – mostly. (There is a small error in the subs for Outside the Law, where “stationery” is misspelled as “stationary” in one scene. At this point, I’m looking hard for things to comment on and criticise; we’ll skip to the chase in the “Overall” section of this review, but it should be evident already that this set represents an excellent proposition in terms of audiovisual presentations of the four films that it contains.)

Extras

DISC ONE DISC ONE

- Calcutta (83:17). - Commentary by Nick Pinkerton. Critic Pinkerton offers a well-researched commentary that explores the production history of Calcutta and the positioning of the film between the wartime thriller and the post-war film noir. Pinkerton examines the stardom of Alan Ladd and the development of the actor’s career, and offers a consideration of the input of some of the film’s key crew and cast members. - “A Man’s Man” (14:12). Critic Jon Towlson provides a video essay exploring Calcutta’s position within the career of its star, Alan Ladd. Towlson explores Ladd’s embodiment of a specific era of masculinity, and the intersection between this and the paradigms of film noir. Towlson also explores Calcutta’s origins in wartime stories and the development of the project. - Trailer (2:20). - Gallery (41 images).  DISC TWO DISC TWO

- Ride the Pink Horse (101:20). - Commentary by Josh Nelson. Critic Nelson explores Ride the Pink Horse’s relationship with the broader category of film noir, suggesting the picture has an “outsider status” within that paradigm. Nelson suggests the film depicts the border town setting as a liminal space in which issues of gender and class are “played out.” Nelson foregrounds the film’s exploration of race (or ethnicity), implying that this is a central element of the picture that is “intimately connected” to the film’s other themes. - “Behind the Dream of the White House” (14:30). Critic Alexandra Heller-Nicholas narrates a video essay that explores the manner in which Ride the Pink Horse amplifies some of the traits of other films noir. She highlights Montgomery’s role in the production of the film, and explores how the film subverts some of the themes and conventions of contemporaneous films noir. - Radio Play (59:33). This is the Lux Radio Theater adaptation of Dorothy B Hughes’ novel, featuring Robert Montgomery, Wanda Hendrix, and Thomas Gomez. - Gallery (6 images).  DISC THREE DISC THREE

- Outside the Law (81:18). - Commentary by Richard Harland Smith. Richard Harland Smith offers a conversational commentary that explores the production context of Outside the Law, examining the career of its director, Jack Arnold. Smith highlights the careers of the cast and crew, his comments often tied directly to what is happening within each scene. - “Father Knows Best” (18:59). Kat Ellinger narrates a video essay exploring the career of Jack Arnold, the director of Outside the Law. Ellinger highlights the impact on later filmmakers of Arnold’s work in more fantastical genres, and explores the origins of Arnold’s career, and his work in Hollywood studios and for television. Ellinger examines the positioning of Outside the Law within post-war film noir, considering in particular the depiction of masculinity in post-war noir. - Trailer (2:07). - Gallery (9 images).  DISC FOUR DISC FOUR

- The Female Animal (82:20). - Commentary by David Del Valle and David DeCouto. Del Valle and DeCouto provide a warm commentary. DeCouto and Del Valle both admit to having never seen The Female Animal previously though they were both aware of its reputation. - “Behind the Curtain” (12:49). This is a video essay written and narrated by Alexandra Heller-Nicholas. Heller-Nicholas foregrounds the similarities between this film and Wilder’s Sunset Blvd., highlighting the films’ shared focus on ageing starlets and their younger male lovers. Heller-Nicholas explores The Female Animal’s use of Hedy Lamar (this was her final film role) and its depiction of femininity, focusing on the film’s focus on Hollywood stars like Lamar (and, later, Monroe et al). - Gallery (9 images).

Overall

Arrow’s new collection of films noirs features a diverse range of pictures. The strongest of these is, almost inarguably, Robert Montgomery’s excellent Ride the Pink Horse. However, that’s not to slight the other films in this set. Calcutta is a near-quintessential post-war film noir that, despite owing some heavy debts to predecessors (most obviously, Casablanca), manages to offer much – particularly in terms of its exploration of Alan Ladd’s screen persona. Outside the Law is very much an example of mid-1950s film noir, leaning into a focus on organised crime. The Female Animal is the only ‘scope film in this set, and unlike the others has a strong focus on a female point-of-view (natch, arguably, given its title) – featuring strong “callbacks,” in particular, to James M Cain’s Mildred Pierce. Arrow’s new collection of films noirs features a diverse range of pictures. The strongest of these is, almost inarguably, Robert Montgomery’s excellent Ride the Pink Horse. However, that’s not to slight the other films in this set. Calcutta is a near-quintessential post-war film noir that, despite owing some heavy debts to predecessors (most obviously, Casablanca), manages to offer much – particularly in terms of its exploration of Alan Ladd’s screen persona. Outside the Law is very much an example of mid-1950s film noir, leaning into a focus on organised crime. The Female Animal is the only ‘scope film in this set, and unlike the others has a strong focus on a female point-of-view (natch, arguably, given its title) – featuring strong “callbacks,” in particular, to James M Cain’s Mildred Pierce.

There’s something in this set to please fans of 1940s and 1950s films noirs, with each of the films benefitting from an excellent presentation and some impressive contextual material. Full-sized screengrabs. Please click to enlarge. Calcutta

Ride the Pink Horse

Outside the Law

The Female Animal

|

|||||

|