|

|

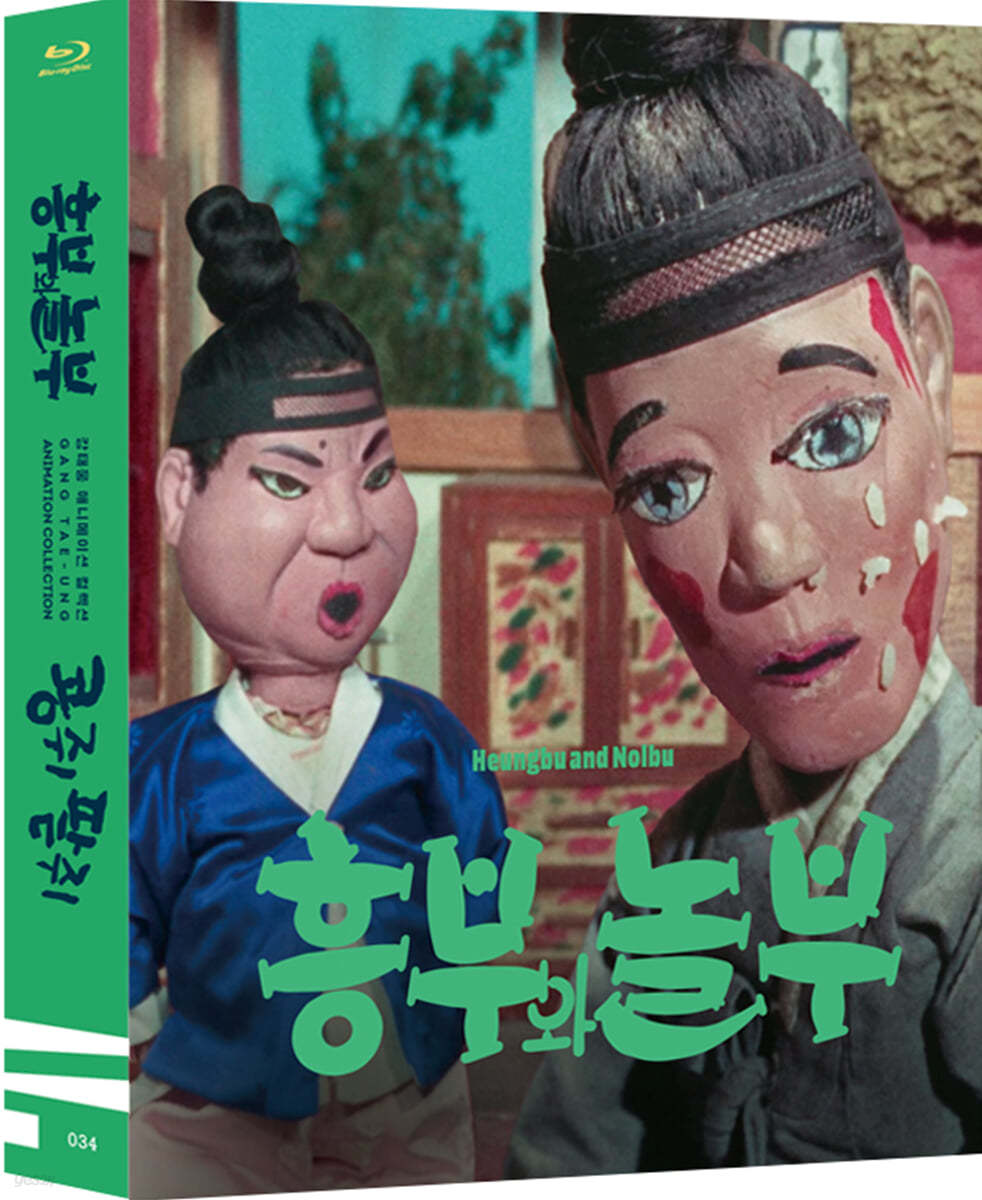

Gang Tae-ung Animation Collection

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - South Korea - Korean Film Archive/Blue Kino Review written by and copyright: James-Masaki Ryan (26th January 2024). |

|

The Film

Gang Tae-ung Animation Collection Gang Tae-ung was born in Hwanghae Province, Korea in 1929. Although he enrolled in a law school when he was 17, he dropped out three years later, stowed away on a boat headed for Japan, and enrolling in Nihon University to study film and arts two years later. He would work on assisting in documentary works following graduation, but a major change came in 1956 when he joined the Ningyo Eiga Seisakujo (Puppet Animation Film Studio), a studio established by Tadahito Mochinaga and Kiichi Inamura a year prior. The studio produced animated shorts and feature films by using crafted puppets and shooting them moving one frame at a time. Stop motion animation was a time consuming and laborious project, and Mochinaga had some expertise in the craft during his time working at an animation studio in China during the wartime years and after, and in 1956, the new studio’s short film “Uriko-hime to amanojaku” became the first stop motion animated work made in Japan. This was followed by the short “Five Little Monkeys”, which Gang worked on in an uncredited form for the studio in the same year. Following the death of Inamura in 1960, Mochinaga closed its doors and established MOM Production, which would partner with American producers Arthur Rankin Jr. and Jules Bass of Rankin/Bass, in which Mochinaga and his team of craftsmen would create some of America’s most beloved stop motion works in the 1960s. With shorts like “Rudolph the Red Nose Reindeer” (1964) and “The Little Drummer Boy” (1968), to feature length films like “The Daydreamer” (1966) and “Mad Monster Party?” (1967), Mochinaga’s works were beloved in the English speaking world, in addition to MOM Production’s works on children’s shows and more in his home country. Gang Tae-ung did not follow Mochinaga, but instead returned to his home country, which was now divided into two Koreas in 1958. He would work in film and on stage, by first directing and acting in the live action feature film “An Angel in White and a Humpback” in 1959. This was followed by directing the live action feature “Forbidden Lips” in 1965. (Unfortunately both films are considered lost.) In 1962, he was able to make use of his expertise in stop motion by working on a television commercial, and this was followed by some short films using stop motion. In 1967, Gang would have the opportunity to create the first stop motion animated Korean feature, and it would be an adaptation of a classic Korean folktale. "Heungbu and Nolbu" <흥부와 놀부> (1967) Heungbu and Nolbu are brothers. Heungbu is a kind hearted man, as are his wife and his eight young children. Nolbu on the other hand is greedy and frequently manipulated by his controlling wife. After the passing of their father, Nolbu and his wife state state that Heungbu and his family must leave the family property empty handed. Forced out, the family find an abandoned home where they would go through difficulties of finding enough work and food for everyone. One day Heungbu spots a small sparrow which has an injured leg from a snake attack. He brings it home and his family helps the bird heal until it can fly back home. After its recovery, the sparrow along with its family bring Heungbu’s family a gourd as a gift, which is filled with silk garments and gold. But when Nolbu and his wife hear that the younger impoverished brother suddenly found riches, they try to seize the opportunity to try a similar feat for themselves, leading to consequences for their greed… It is believed that the anonymously told story originated in the late Joseon Dynasty (1800s). The moral tale of punishment for greediness and rewards for kindness can be found in fairy tales and myths from all over the world, and in this case there is also the fantasy element with animals that is common with many Asian cultures. Some audiences may ask by the younger brother never fought for his right to inheritance or argue against the many setbacks. But this is a basic moral tale of right and wrong, without a grey area to make things complex. The tale is basically for children to comprehend about consequences for actions in a simplistic way, and there never needs to be a situation of Nolbu fighting for what was right. He consistently shields himself for the sake of his family, including taking beatings, or not telling his wife the truth about what happened when meeting his brother again, so he could spare her heart from heartbreak. His concern is to give his children food and shelter, and even in dire circumstances, it shows that greatness can come through honesty and hard work. The story has been told and retold so many times over the years in various forms with changes along the way, and this includes modern adaptations in songs, plays, musicals, and film. In January of 1967, Korea’s first cel animated feature, “A Story of Hong Gil-dong” was released to great acclaim and packing audiences in theaters. The Eunyeong Film Company looked to ride off the hit film, and enlisted director Gang Tae-ung who worked in stop motion animation, to create a feature length film that would also be an adaptation of a classical story. Gang assembled a small team of animators from February that year and worked diligently for months in a laborious process of shooting one frame at a time, at 24 frames per second for a feature that would be close to 70 minutes long. The puppets were created from steel parts for the base and having wooden components, along with fabric for garments, with each figure standing between 20 to 30 centimeters tall. Everything from the houses to the backgrounds had to be crafted by hand, as well as for each movement of each character. Facial expressions were interchangeable with mouths and eyes, though smaller gestures such as fingers were not. Fishing wire was used for some situations such as jumping or objects in the air, though they were infrequent. Camera movement was also an infrequent as moving the camera one frame at a time would easily cause jittering of the frame, though it is done in some moments. As these were the early days in which each frame that was taken could not be seen until the entire film reel was developed, it was impossible to spot check if what was moved before and after were correct or not, or if something mistakenly appeared in the background for a second. There are several shots in which shadows of the crew (basically Gang, as he was the only puppeteer on the film) are visible for a split second because the shutter was closed when a crewmember was standing in front of the light by mistake, but these are the small things that also prove how handmade these works were. It brings life to the inanimate and wonder to children’s eyes to see something physically existing in toy boxes in moving living reality. There are some technically impressive moments such as burning candles being visible and flickering in a seemingly correct way (although the wax melting speedily in some shots give away how long it took to film the actual scene). There are also shots with all ten members of Heungbu’s family in a single shot, meaning the animator hand to remember the positions of each and every character that was being made. The completed film was released in theaters on July 30th, 1967. Although it was not a blockbuster hit for Eunyeong Co, it was enough to make a profit, and was a critical hit, winning Best Film in the non-feature film category at the 5th Blue Dragon Awards. The film was the first of its kind in the country, and it was a difficult sell considering the lengthy time it took to create and the amount of profit it brought in. Gang was at the time also working as a lecturer for theater and film at Seorabeol University, and it would be a full decade until he would be brought back into the world of puppet animation. "Kongjwi and Patjwi" <콩쥐 팥쥐> (1978) Kongjwi is the only child of her family, raised by her single father after her mother’s passing. One day her father remarries and Kongjwi gains a stepmother and a younger step-sister. But the stepmother is cruel and the step-sister Patjwi is rowdy and selfish. She takes all of Kongjwi’s nice clothes and makes her dress in rags instead. The stepmother makes Kongjwi do all the household chores and farmwork, in addition to beating her for any small mistake. While the step-mother and sister are nice when the father is around, Kongjwi never mentions to her father of the mistreatment she is receiving. One day she encounters a small deer that was struck by a hunter’s arrow and she tends to its injuries. The hunter is Kim, a young man who is studying to become a statesman and immediately falls in love with Kongjwi’s kindness. Though it becomes difficult for them to meet face to face due to his time having to be away for government exams and because of Kongjwi’s controlling step-mother, fate would say otherwise, where the kind-hearted are gifted and the greedy are punished… This folktale also dates back to the Joseon Dynasty, and it is also from an anonymous source. As it was passed from generation to generation orally before anything was written, each telling had its share of changes over time. Even this film adaptation by Gang Tae-ung has a number of differences from the more well known versions. Like many folktales it divides the good and the bad with a clear line and the characters never cross from one to the other. There are portions in which one might think a character may have a change of heart, such as Patjwi realizing her ways do not lead to positive circumstances, but her mind is set on the easy path and through laziness. It is easy to hate the step-mother and step-sister, though there are some wonderfully funny scenes such as when Patjwi is awakened by Kim’s mother who visits and gets an earful. The moments of cruelty from the step-mother are frustrating for the audience, as one would think Kongjwi should retaliate or have her father get involved. But like “Heungbu and Nolbu”, it is about dealing with the cruel situation and having optimism that righteousness would come, and in this case it is with Buddha, helping and rewarding Kongjwi for her sacrifices. There is also a sequence in which Kongjwi loses her shoe, which is later retrieved by a statesman, leading to an area wide search for the owner of the shoe, conducted by the statesman, who happens to be Kongjwi’s fateful interest Kim. With a lost shoe and an evil step-mother making her step-daughter do chores while her actual daughter gets to be free, there is obvious similarities to the well known tale of “Cinderella”. The origin of the fateful story can be dated back centuries to ancient Greece and possibly further back, with the story being told in various forms and various countries around the world, with each having its own distinctions. As stated before, this version of “Kongjwi and Patjwi” has some differences from other versions of the story, such as in here the statesman is around the same age as Kongjwi, while in other versions he is much older. Kongjwi is pushed into a deep pond by Patjwi here, rather than in a river and the outcome for the scenario is also slightly different. This also goes for the punishment for Patjwi and the step-mother at the end of the tale. But regardless of the differences, the main focus of good over evil and overcoming hardship through patience and hard work is no different. Following South Korea’s foray into feature animation with director Shin Dong-ho’s cel animated “A Story of Hong Gil-dong” and “Hopi and Chadol Bawi” plus the stop motion “Heungbu and Nolbu” all in 1967, there was a market for the artform for the next few years. Unfortunately things hit a standstill in the early 1970s with arguments and negotiations between the studios. Famed filmmaker Yu Hyon-mok was a fan of the artform and produced the cel animated sci-fi feature “Robot Taekwon V” in 1976, which became a major hit for audiences and created a much needed boost for Korean animation. With its success, the film would start a franchise of animated theatrical films that would be released every year until 1979, with three additional features in later years. Yu also enlisted Gang Tae-ung to return to the director’s seat for a stop motion animated feature, and for his second animated film it was again a folktale that was known to all Koreans. When comparing “Heungbu and Nolbu” to “Kongjwi and Patjwi”, it’s difficult to believe that there was a decade long gap between the two as technologically the improvements are subtle to say the least. Some of the animal characters look quite similar in design, as does the sets though they are newly created rather than using existing models. Camera movement is as jittery as it was, and character movement is also quite stiff to say the least. Granted there were no stop motion features produced in the country for the last decade, so it is not a surprise that no major advances would be made. Like before, the characters had limited movement but there was character and depth provided through subtle techniques and they are brought to life through childlike wonder through the gifted hands of Gang and his small team. There are also some improvements seen in the interchangeable eyes of characters as well as moveable fingers for the puppets. Flaws can sometimes be found with shadows appearing and disappearing, positions of leaves or grass changing suddenly, and more that is expected with the analog technology of stop motion filmmaking. The film was released theatrical on January 23rd, 1978, and like Gang’s previous film it was not a major hit but still enough for a profit. Gang would continue working as a professor and lecturer in universities until he retired in 1994. Although his films were mostly forgotten and South Korea never fully embraced stop motion as a viable artform for major commercial work, it was a surprise when he received a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Seoul International Cartoon & Animation Festival in 2007. Gang Tae-ung passed away in 2015 at the age of 86. After a dry spell of 45 years, in 2023, animator Park Jae-beom’s “Mother Land” became the third South Korean film to be animated using stop motion to rave reviews. Even in the digital age, the artform is a difficult sell compared to its counterparts in 2D and 3D. But there is a charm to the style that cannot be matched by other techniques, and the pioneers should be appreciated for their works. Both of Gang Tae-ung’s animated features fortunately survive with negatives and prints being stored at the Korean Film Archive, and in 2021 they were both digitally restored in 4K and now available on Blu-ray for the first time. Note this is a region ALL Blu-ray set

Video

The Korean Film Archive/Blue Kino presents both films in the 1.37:1 aspect ratio in 1080p AVC MPEG-4. Both films were restored in 4K resolution, using the original 35mm negatives in 2021 by the Korean Film Archive and Image Power Station. As original elements for both films survived and have been stored at the Korean Film Archive, it would assume that the restorations would be fairly easy to accomplish. But the problems that faced the restoration team were different from those found in previous restorations by KOFA. Similar to the to the problems faced in the restorations of "A Story of Hong Gil-dong" and "Hopi and Chadol Bawi", there were issues inherent to the animation filmmaking process that differed from restoring live action feature films. Because stop motion is shot frame by frame at 24 frames per second non-consecutively, there are inconsistencies such as blades of grass, shadows, and other portions moving ever so slightly from frame to frame. When the film is put through digital restoration software, it detects anomalies in the subsequent frames such as scratches, debris, film warping, shrinkage, and digitally corrects any errors that is detected as damage. But in the case of stop motion animation where each frame could have significant unnatural differences due to the handcrafted behavior, digital restoration could not be relied on entirely. Manual checks had to be done to make sure that actual damage on the film itself would be removed and not something that was originally part of the filmmaking process. Another issue was the inconsistency of lighting, with flickering that happened during the actual filmmaking process where the brightness would minutely change from frame to frame. Although this was how the film looked due to the limitations of the time, digital correction was applied to make sure brightness and the colors to stay consistent within the scenes for the restoration. Colors here look absolutely vibrant from the wardrobes to the model sets and the restoration has brought new life into these long forgotten gems. Detail is exceptional with each puppet looking wonderful, even if they are not of the cutest in appearance. Film grain has been left intact while almost all damage marks have been removed for a pristine looking image throughout for both features. Absolutely solid works on the 4K restorations for both of the features. The films are placed on separate BD25 discs and are given a fair amount of space for their fairly short runtimes, so there are no issues of compression to be spotted with the transfers. The runtime for "Heungbu and Nolbu" is 69:14, which includes restoration text at the start. The runtime for "Kongjwi and Patjwi" is 73:04, which includes restoration text at the start.

Audio

Korean LPCM 1.0 The original Korean language mono tracks are presented in uncompressed form for both features. The sound was also remastered from original film elements. As all dialogue, music, and effects were post-synchronized, there are not many faults to speak of, with the restoration applied to the sound. The audio is slightly on the low volume side for both films, but on the brighter side there are no issues of hiss, pops, or other damage to the audio, and the dialogue is well balanced against the music and effects. A solid job on the sound restoration as well from KOFA. There are optional English, Japanese, Korean subtitles for both features in a white font. They are well timed and easy to read, though there were rare occasions of grammatical mistakes to be found for both films.

Extras

This is a two disc Blu-ray set with "Heungbu and Nolbu" on DISC ONE and "Kongjwi and Patjwi" on DISC TWO, with following extras included. DISC ONE Audio commentary by Park Jae-beom (director) and Kim Bo-nyun (Seoul Art Cinema programmer) Stop motion animator Park Jae-beom is joined by programmer Kim Bo-nyun for this new commentary track on "Heungbu and Nolbu". Unfortunately there are no English subtitles available for non-Korean speakers. in Korean Dolby Digital 2.0 without subtitles "Heungbu and Nolbu: A Swallow Has Returned" 2023 short (3:27) Presented here is a short film by Yona Animation Studio and directed by Park Jae-beom who lent his comments to the commentary above, which is a dialogue-free showcase of the animals bringing and opening the differing gourds, inspired from the story of “Heungbu and Nolbu”. The story is told through shadow puppetry, with puppeteers dressed in all black as they manipulate the very intricately crafted figures. in 1080p AVC MPEG-4, in 1.78:1, in Dolby Digital 2.0 without subtitles "A Way to Live Well" 1963 short (9:26) Director Park Yeong-il made the impressive cel animated color short "The Ant and the Grasshopper" in 1961 (which was recently released as a bonus feature on the Korean Film Archive Blu-ray of Shin Dong-hun Animation Collection. For this 1963 short, Park relies on stop motion animation, stillframe artwork, as well as cel animation to tell a story about people having to work hard for the greater good and economic development for this educational film. The transfer has not gone through any restoration, so there is flickering of colors, speckles and scratches on the image, and some weak audio to be heard. Strangely, it is mostly presented in a widescreen ratio, while some shots that showcase numbers and figures slightly windowbox the image to the 1.33:1 aspect ratio. Color film. Flickers, speckles, scratches. Sequences with numbers and figures windowbox to 1.33:1, in 480i MPEG-2, in 1.75:1, 1.33:1, in Korean Dolby Digital 2.0 without subtitles DISC TWO Audio commentary by Jeon Seong-bae (director) and Kim Bo-nyun (Seoul Art Cinema programmer) Stop motion animator Jeon Seong-bae is joined by programmer Kim Bo-nyun for this new commentary track on "Kongjwi and Patjwi". Unfortunately there are no English subtitles available for non-Korean speakers. in Korean Dolby Digital 2.0 without subtitles "Puppet Story" 2022 short (14:30) This short film by animator Park Se-hong is a metaphysical one, with the director playing himself as a stop motion animator looking to produce a new project with his puppets, but while he is out of the studio, the puppets come to life and lament over the fact that their old fashioned and cumbersome artform is not as accepted in comparison to modern 3D animation. The animation is well done with the characters of the fighter, the demon, and the woman coming to life in traditional stop motion form and also makes reference to the films of Gang Tae-ung while the puppets go through an old scrapbook. Shot digitally, the image and sound are as sharp as one should expect with a new production. in 1080p AVC MPEG-4, in 1.78:1, in Korean Dolby Digital 2.0 with optional English subtitles Book An 80 page book is included, with text in Korean for the first half and translated to English for the second half. First are crew listings and synopsis for both films, followed by a biography and filmography of the director. The first essay is "The Beginning of Korean Puppet Animation" by animation researcher Han Seungtae, which goes into the director's life, his works leading to his two features and an analysis for both features. Next is "Director Gang Tae-ung, who I met in 2007, and the first reunion in 50 years across the border" by Kim Joon-yang, an associate professor at Niigata University in Japan. This is a fascinating story of the professor being able to meet the director for a film retrospective and the director eventually reconnecting with the wife of his mentor Tadahito Mochinaga many decades later. There are also lengthy restoration notes for both films by Kim Kiho of KOFA, notes on the bonus shorts, as well as various stills from the film and archival materials. There are one or two grammar errors in the booklet, though to say it is much better written and translated in comparison to KOFA's "Shin Dong-hun Animation Collection" booklet.

Packaging

The discs are packaged in a foldout Digipack case which also holds two postcards, featuring poster art for the two films. The case along with the book are housed in a slipcase, labeled as #34 on the spine. The packaging mistakenly claims the sound is Dolby Digital for both films and the aspect ratios for the films being 16:9.

Overall

"Gang Tae-hung Animation Collection" is yet another solid release from the Korean Film Archive, this time showcasing the first two stop motion feature films made in Korea. While the filmmaking techniques may fall behind in the contemporary stop motion works seen in America, Japan, or Europe at the time, they are still quality gems that showcase the intricacies and flaws of the human touch, not just in construction but also with the content. The Blu-ray set has excellent transfers for both films and a good selection of extras, though again note that not all the extras offer English subtitles. Still comes as highly recommended. Note that the 4K restoration of "Kongjwi and Patjwi" is available to watch for free with optional English subtitles on KOFA's Animation YouTube Channel. "Heungbu and Nolbu" is currently not available on their channel.

|

|||||

|