|

|

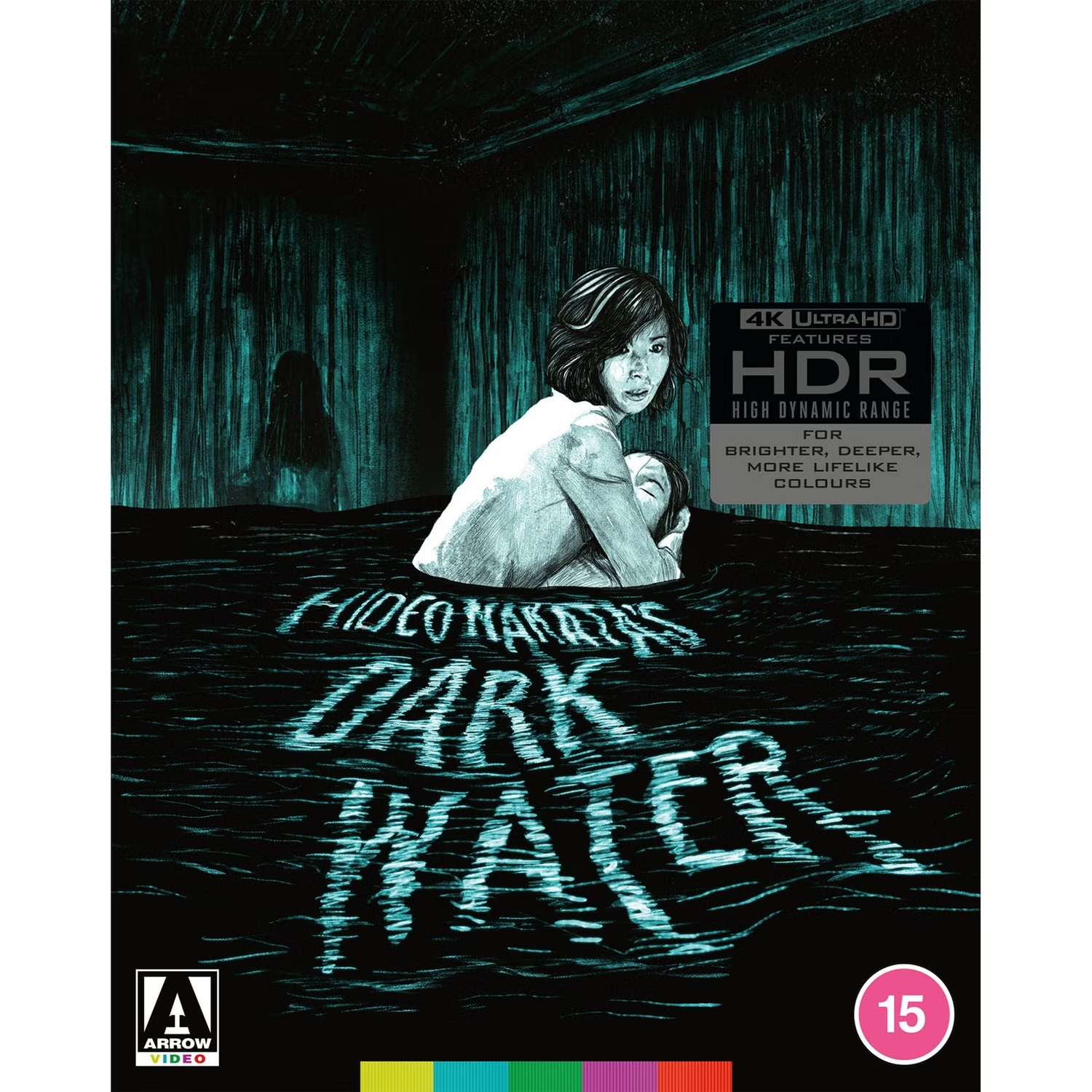

Dark Water AKA Honogurai Mizu no soko kara (Blu-ray 4K)

[Blu-ray 4K]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (18th March 2024). |

|

The Film

Dark Water (Nakata Hideo, 2002) Dark Water (Nakata Hideo, 2002)

With their new 4k UHD release of Nakata Hideo’s Dark Water, Arrow Video have revisited a key ‘J-horror’ film that, almost ten years ago, they previously released on Blu-ray. Made during the boom period in production of ‘J-horror’ (Japanese horror) films that took place in the wake of breakout pictures like Miike Takashi’s Audition (1999) and Nakata Hideo’s The Ring (1999) – films which had a cross-cultural appeal – Nakata Hideo’s Dark Water (2002) was based on a short story by Suzuki Koji, the same author of the novel from which The Ring had been adapted. Kim Newman has referred to Dark Water as ‘among the best of the trend’ (ie, ‘J-horror’ films) (Newman, 2011: 424). Like The Ring before it, Dark Water was also the subject of a lackluster Hollywood remake – one of a number of such remakes of ‘J-horror’ and ‘K-horror’ (Korean horror) films of the early 2000s that attempted to replicate the cross-cultural success of the original films as if trying to capture lightning in a bottle. The film begins with a flashback showing a young girl left behind at school: her parents have failed to collect her. We then cut to Matsubara Yoshimi (Kuroki Hitomi), the little girl now grown up, as she waits to discuss her impending divorce with her lawyer. Yoshimi’s husband refuses to give up custody of the couple’s six year old daughter, Ikuko (Kanno Rio), and this is a source of concern for the already pressured Yoshimi. Yoshimi and Ikuko move into a rundown apartment in a seemingly near-deserted complex. The apartment is rundown, a stain on the ceiling indicating water damage to the floor above; water drips into the lift from above; Yoshimi finds hair in the tap water. Whilst exploring the rooftop of the building alone, Ikuko discovers a child’s bag there. The bag bears the name ‘Mitsuko’, although the building’s caretaker says that no children live in the building. However, during a visit to the washroom Yoshimi finds that the lift inexplicably stops on the floor above the one on which her apartment is situated, and there she glimpses the ghostly figure of a little girl who appears to be of a similar age to Ikuko.  No matter how many times Yoshimi tries to discard the bag Ikuko found on the roof of the building, it keeps finding its way back into the apartment. Ikuko also begins talking with an imaginary friend, ‘Mit-chan’. Whilst at school one day, Ikuko has a mysterious encounter with another student and faints. Yoshimi is called to bring the feverish Ikuko home. One night, whilst Yoshimi sleeps, Ikuko manages to escape from the apartment. Yoshimi finds her on the floor above, discovering that the apartment directly above hers was once owned by Mitsuko’s mother and is now badly flooded. Yoshimi tells her husband ‘Mitsuko has returned to the apartment upstairs and she’s trying to take Ikuko away’. After reaching a settlement with her husband and effecting a reconciliation with him, Yoshimi experiences a vision suggesting to her that Mitsuko drowned after falling into the water tank that sits on top of the building. No matter how many times Yoshimi tries to discard the bag Ikuko found on the roof of the building, it keeps finding its way back into the apartment. Ikuko also begins talking with an imaginary friend, ‘Mit-chan’. Whilst at school one day, Ikuko has a mysterious encounter with another student and faints. Yoshimi is called to bring the feverish Ikuko home. One night, whilst Yoshimi sleeps, Ikuko manages to escape from the apartment. Yoshimi finds her on the floor above, discovering that the apartment directly above hers was once owned by Mitsuko’s mother and is now badly flooded. Yoshimi tells her husband ‘Mitsuko has returned to the apartment upstairs and she’s trying to take Ikuko away’. After reaching a settlement with her husband and effecting a reconciliation with him, Yoshimi experiences a vision suggesting to her that Mitsuko drowned after falling into the water tank that sits on top of the building.

The film parallels the childhoods of Yoshimi and Mitsuko. The opening flashback shows Yoshimi as a child, waiting for her parents to collect her from school. The parents never arrive; Yoshimi is left waiting. (Later flashbacks suggest that Yoshimi’s mother simply fled mysteriously.) The film cuts to the adult Yoshimi waiting for the meeting about her impending divorce, connecting the past and the present and establishing the fact that the previous scene was Yoshimi’s memory. The flashback is shot with a strong yellow filter. Later flashbacks, also shot with the same yellow filter, focus on Mitsuko, who these analepses show experienced a similar fate: left alone at the school, waiting for her parents before making her own way back to the apartment complex where she died.  Like a number of its contemporaneous ‘J-horror’ pictures, Dark Water features what seems to be an onryō, or vengeful ghost that is potentially capable of harming the living. (That ghost is, of course, Mitsuko.) Vicky Lebeau has listed Dark Water as amongst the significant number of films that focus on ‘the idea of the uncanny child as both subject and object of terror’ (Lebeau, 2008: np). These films include Village of the Damned (Wolf Rilla, 1960), Jack Clayton’s The Innocents (1960), William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973), Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973), Tobe Hooper’s Poltergeist (1980), Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), Children of the Corn (Fritz Kiersch, 1984) and, most pertinently to Dark Water, Shimizu Takashi’s Ju-On: The Grudge (2003). Like a number of its contemporaneous ‘J-horror’ pictures, Dark Water features what seems to be an onryō, or vengeful ghost that is potentially capable of harming the living. (That ghost is, of course, Mitsuko.) Vicky Lebeau has listed Dark Water as amongst the significant number of films that focus on ‘the idea of the uncanny child as both subject and object of terror’ (Lebeau, 2008: np). These films include Village of the Damned (Wolf Rilla, 1960), Jack Clayton’s The Innocents (1960), William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973), Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973), Tobe Hooper’s Poltergeist (1980), Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), Children of the Corn (Fritz Kiersch, 1984) and, most pertinently to Dark Water, Shimizu Takashi’s Ju-On: The Grudge (2003).

Early in the film, Yoshimi is suggested to be an unreliable narrator when it is revealed, during the divorce proceedings, that she underwent psychiatric treatment a decade prior to the events depicted in the film. Yoshimi protests that this was simply owing to her having to proofread some incredibly explicit material in her previous employment at a publishing company, but nevertheless doubt is cast in the mind of the viewer as to whether the supernatural events Yoshimi witnesses subsequently are ‘real’ or simply figments of Yoshimi’s imagination. As the film progresses and the supernatural occurrences escalate, Yoshimi notices the water stain on the ceiling of her new apartment spreading; the water stain becomes a symbol of Yoshimi’s mental deterioration. The revelation of Yoshimi’s prior mental health issues also casts doubt on Yoshimi’s efficacy as a parent, and a number of times in the film she displays poor judgement in caring for Ikuko (something will be recognisable to any parent of a child of similar age), leaving the young girl alone in the apartment when she explores the roof of the complex, for example. At one point in the film, having started a new job Yoshimi is extremely late collecting Ikuko from school, unintentionally repeating the cycle of neglect that Yoshimi herself suffered as a child. Yoshimi finally arrives at the school to find it closed and Ikuko gone. Fortunately, Ikuko has been collected by her father instead, but Yoshimi is angered about this, believing the incident will undermine her attempts to maintain custody of Ikuko. (‘Standing there all alone, do you know how that feels?’, Yoshimi’s husband asks her in reference to Ikuko’s plight; he is presumably unaware of the details of Yoshimi’s past.)  Much is made early on in the film about Yoshimi’s husband’s refusal to give up custody of Ikuko: in Japan, divorce tends to favour the ‘clean break’, usually leaving the husband with no economic commitment to his former spouse but also no contact with any children they may have together, whilst the wife is often left with the children but no means of financial support. Whilst Yoshimi complains to her lawyer that ‘He’s [her husband has] never taken care of [Ikuko], not once’ – to which her lawyer replies, ‘Perhaps it’s just that you have never noticed’ – it does seem that Ikuko’s father is not a bad parent. In fact, the opposite is true: from what little we see of him (he’s largely sidelined by the narrative), it seems he cares deeply for his daughter. On the other hand, it seems more a case of Yoshimi being an overbearing and controlling (but conversely, also neglectful) mother. Much is made early on in the film about Yoshimi’s husband’s refusal to give up custody of Ikuko: in Japan, divorce tends to favour the ‘clean break’, usually leaving the husband with no economic commitment to his former spouse but also no contact with any children they may have together, whilst the wife is often left with the children but no means of financial support. Whilst Yoshimi complains to her lawyer that ‘He’s [her husband has] never taken care of [Ikuko], not once’ – to which her lawyer replies, ‘Perhaps it’s just that you have never noticed’ – it does seem that Ikuko’s father is not a bad parent. In fact, the opposite is true: from what little we see of him (he’s largely sidelined by the narrative), it seems he cares deeply for his daughter. On the other hand, it seems more a case of Yoshimi being an overbearing and controlling (but conversely, also neglectful) mother.

Although the subject matter is quintessentially Japanese, the film contains some visual references to American horror pictures like Kubrick’s The Shining: a shot in which Ikuko sits and waits outside the elevator, only for the doors to open and an immense flood of water to spill out of the elevator and engulf her, is strongly reminiscent of the famous shot of Danny Torrance’s vision of the elevator doors in the Overlook Hotel opening and blood pouring out of the elevator shaft. Alison Peirse has suggested that one of the reasons for the transnational appeal of a number of ‘J-horror’ films of this period, including Dark Water, is the focus on the relationships between parent and child (usually in these films, mother and child) (Peirse, 2013: 151). K K Seet has referred to these films as a form of ‘domestic gothic’, reworking the tropes of traditional Gothic fiction in a modern Japanese domestic setting (Seet, cited in ibid.: 176). In the film’s focus on this archetype, Colette Balmain has connected Dark Water specifically with a moderately long-standing tradition in American horror films to focus on ‘the break-up of the nuclear family’ (Balmain, 2008: 128). These films include, of course, The Shining, The Amityville Horror (Stuart Rosenberg, 1979), Poltergeist and The Stepfather (Joseph Ruben, 1987) (Balmain, 2008: 128). However, where most American horror films that explore this theme focus on ‘the sins of the father’ and corrupt patriarchs (such as Jack Torrance), the ‘J-horror’ pictures tend to examine ‘the sins of the mother, and her daughter as her double, that return to threaten the home as microcosm of society, signifying the persistence of trauma, both historical and economic’ (ibid.).  Speaking of economic trauma, Elisabeth Scherer suggests that the ‘creepy damp apartment building’ into which Yoshimi and Ikuko move is a symbol of Japan’s ‘lost decade’: the recession that took place in the 1990s which ended the ‘bubble’ economy of the 1980s (Scherer, 2016: 73). Like Ju-On: The Grudge, the film uses a surveillance camera to indicate the presence of the supernatural within the apartment building. Mitsuko’s lonely death, caused by her falling into the water tank on the roof of the building, could be taken as a metaphor for the economic collapse faced by Japan in the 1990s. The presence of her decaying corpse in the water tank, the viewer will realise partway through the film, is the source for the hair that Yoshimi has been finding in the tap water; the implication that Yoshimi and Mitsuko have been drinking water contaminated by the corpse of Mitsuko is subtle and disturbing. Bizarrely, the film found a real life corollary a few years later, in the strange death of student Elisa Lam, who drowned after falling into the water tank on top of Los Angeles’ Cecil Hotel in 2013, her body only being discovered a month after her death following complaints from the residents about the water being potentially contaminated. (Even more strangely, in terms of how the circumstances echoed the plot of Dark Water and its focus on the lift that carries Yoshimi and Ikuko between floors, security camera footage from the elevator of the Cecil Hotel showed Lam displaying extremely odd behaviour – as if communicating with an unseen person – prior to her death.) Speaking of economic trauma, Elisabeth Scherer suggests that the ‘creepy damp apartment building’ into which Yoshimi and Ikuko move is a symbol of Japan’s ‘lost decade’: the recession that took place in the 1990s which ended the ‘bubble’ economy of the 1980s (Scherer, 2016: 73). Like Ju-On: The Grudge, the film uses a surveillance camera to indicate the presence of the supernatural within the apartment building. Mitsuko’s lonely death, caused by her falling into the water tank on the roof of the building, could be taken as a metaphor for the economic collapse faced by Japan in the 1990s. The presence of her decaying corpse in the water tank, the viewer will realise partway through the film, is the source for the hair that Yoshimi has been finding in the tap water; the implication that Yoshimi and Mitsuko have been drinking water contaminated by the corpse of Mitsuko is subtle and disturbing. Bizarrely, the film found a real life corollary a few years later, in the strange death of student Elisa Lam, who drowned after falling into the water tank on top of Los Angeles’ Cecil Hotel in 2013, her body only being discovered a month after her death following complaints from the residents about the water being potentially contaminated. (Even more strangely, in terms of how the circumstances echoed the plot of Dark Water and its focus on the lift that carries Yoshimi and Ikuko between floors, security camera footage from the elevator of the Cecil Hotel showed Lam displaying extremely odd behaviour – as if communicating with an unseen person – prior to her death.)

Video

Presented in 2160p using the HEVC codec, Dark Water is presented on this 4k UHD disc uncut, with a running time of 101:18 mins. The film is presented in its intended theatrical ratio of 1.85:1. Interestingly, this new 4k presentation is much more “opened up” in comparison with Arrow’s 2016 Blu-ray release, with more information visible on all four sides of the frame. Presented in 2160p using the HEVC codec, Dark Water is presented on this 4k UHD disc uncut, with a running time of 101:18 mins. The film is presented in its intended theatrical ratio of 1.85:1. Interestingly, this new 4k presentation is much more “opened up” in comparison with Arrow’s 2016 Blu-ray release, with more information visible on all four sides of the frame.

The presentation is billed on a title card that precedes the film as being based on a ‘2023 Digitally Restored Version’ produced by Kadokawa Corporation and with restoration services provided by Imagica. This new 4k presentation is a significant upgrade over Arrow’s previous Blu-ray release. Captured on Fuji’s quietly efficient 35mm ‘Super F’ film stocks, it’s worth noting that Dark Water appears to be a film that intentionally has a murky, muddy aesthetic – anchored by the opening credits sequence, which feature the film’s main titles playing over a shot of filthy, particle-ridden water with shafts of overhead light struggling to penetrate the grime. It’s a film whose photography is dominated by hues of brown, vomit-y greens, and yellows, and this is captured very well in this 4k release. When compared with Arrow’s previous Blu-ray release, the uptick in terms of detail on this 4k release is evident throughout. Much of the film is comprised of shots of long, empty, and only partially-lit corridors with a strong depth of field that suggests the dominant use of shorter focal lengths within the photography. The sense of visual depth engendered by these shots was articulated well on the previous Blu-ray release, but is even stronger here. The biggest improvement on this new 4k release comes in the contrast levels, enabled by the high dynamic range presentation. The film is filled with low light photography, presented very well here with no sharp curves into the toe or shoulder of the exposure. Highlights are ‘soft’ and not too hot, whilst mid-tones are defined albeit deliberately ‘dull’ (in the sense that it seems that the exposure seems to have been dialled down during principal photography), with the result that this film feels like a picture that takes place almost entirely in a state of perpetual dusk. Blacks are deep and rich. One thing that is noticeable, revisiting the film for the first time in almost a decade, is how much of the narrative is presented via mixed media footage, with the introduction of shots taken from monitors playing back CCTV footage, etc. The texture of this footage is retained, along with the more general structure of 35mm film, by a strong encode to disc. NB. The images used in this review are for illustration purposes only and don’t represent the qualities of this 4k transfer.

Audio

The audio track on this disc is, as on the previous Arrow Blu-ray release, presented in DTS-HD MA 5.1. This track is rich and resonant, capturing the film’s ghostly sense of music and sound design very effectively. There’s some good use of sound separation during some of the more frightening scenes and also to communicate the omnipresence of the rain, with the sound of water hitting the group and dripping from surfaces almost constant throughout the film. The Japanese dialogue is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. These are easy to read and error free.

Extras

The contextual material on this disc is identical to that on Arrow’s previous Blu-ray release. To this end, the disc includes:  - ‘Hideo Nakata: Ghosts, Rings and Water’ (26:03). In a new interview recorded for this release, Nakata discusses his early career with Nikkatsu, where he worked as an assistant director for seven years before graduating to directing in television. He talks about his film Don’t Look Up, which led to Ring and its sequels. Nakata discusses his intention, during the late 1990s, to make a documentary about Joseph Losey. When money ran out for that project, Nakata returned to Japan and made Don’t Look Up. He talks about the popularity of horror films generally, and suggests that he ‘was never head over heels in love with horror films’. He reflects at length about Ring and its relationship with Suzuki’s novel, and talks about some of the film’s themes and how it departs from traditional ghost stories. This interview is in Japanese, with optional English subtitles. - ‘Hideo Nakata: Ghosts, Rings and Water’ (26:03). In a new interview recorded for this release, Nakata discusses his early career with Nikkatsu, where he worked as an assistant director for seven years before graduating to directing in television. He talks about his film Don’t Look Up, which led to Ring and its sequels. Nakata discusses his intention, during the late 1990s, to make a documentary about Joseph Losey. When money ran out for that project, Nakata returned to Japan and made Don’t Look Up. He talks about the popularity of horror films generally, and suggests that he ‘was never head over heels in love with horror films’. He reflects at length about Ring and its relationship with Suzuki’s novel, and talks about some of the film’s themes and how it departs from traditional ghost stories. This interview is in Japanese, with optional English subtitles.

- ‘Koji Suzuki: Family Terrors’ (20:20). Here, in a new interview, the author Suzuki reflects on the film adaptations of his work. He suggests that ‘the scariest thing for me’ is the idea that his daughter might meet with ‘some disaster’. He talks about his early work and how he came to become a novelist. Because he never had a job other than writing, he was under immense pressure to feed his wife and daughter through his craft. The story that inspired Dark Water came about after Suzuki was asked by his editor to come up with a collection of short stories, and he talks about the relationships between his work and traditional Japanese ghost stories. This interview is in Japanese, with optional English subtitles. - ‘Junichiro Hayashi: Visualizing Horror’ (19:16). This new interview features the film’s director of photography talking about his work with Nakata: the pair have collaborated on Ring, Dark Water and The Complex (2013). Describing himself as ‘a bit of a coward’, Hayashi discusses his reticence in watching horror films. He says he was pushed to watching films such as Suspiria (Dario Argento, 1977) ‘by some directors’ who ‘want[ed] me to use them as a point of reference’ – but admits that he never watched these films to the end. Hayashi discusses his early work as an assistant director, before he noticed the camera crew and decided he would rather work in the camera department. He talks about the role of the camera unit and the importance of lighting. This interview is in Japanese, with optional English subtitles. - Making-of Featurette (15:50, SD). In this archival featurette, we are presented with some on the set footage during the production of the film. We see the shooting of part of the film’s closing sequence and the flashback in which Mitsuko is shown leaving school. We are also shown the filming of Yoshimi’s first day at her new job, and the shooting of the climax of the film – which offers a glimpse into the film’s makeup effects. This featurette is in Japanese, with optional English subtitles. - Interviews (all in Japanese, with optional English subtitles): -- Hitomi Kuroki (7:59). In this archival interview, Kuroki talks about how she came to act in the film, her feelings about horror films generally, and how she approached her performance in the picture. -- Asami Mizukawa (4:38). In an archival interview, Mizukawa, who plays the 16 year old Ikuko in the film’s final sequence, is shown auditioning for the part before speaking about her role in the film. -- Shikao Suga (2:54). In an archival interview, Suga discusses the song he composed for the film’s closing titles. - Promo Materials: -- Trailer (1:13). -- Teaser (0:37). --TV Spots (0:50).

Overall

An impressive entry from the boom years of the J-horror cycle, Dark Water succeeds very well and overshadows the deeply lackluster Hollywood remake. The film is enriched by its context; like many of the J-horror pictures of that era, the narrative displays echoes of the ‘lost decade’ in the spaces in which people live and the fallout from that economic crisis that manifests itself in people’s fractured relationships with one another. Dark Water, like other J-horror pictures, inverts the focus on American horror films (to which the picture sometimes refers) on the ‘bad patriarch’ and instead looks at the relationship between a mother and her daughter. The climax has a strong element of ambiguity that will resonate with first time viewers and ensure the film lingers in the memory. Perhaps most importantly, in terms of the film’s cache as part of the horror genre, the fright scenes are realised effectively, and it’s a very well-photographed film overall. An impressive entry from the boom years of the J-horror cycle, Dark Water succeeds very well and overshadows the deeply lackluster Hollywood remake. The film is enriched by its context; like many of the J-horror pictures of that era, the narrative displays echoes of the ‘lost decade’ in the spaces in which people live and the fallout from that economic crisis that manifests itself in people’s fractured relationships with one another. Dark Water, like other J-horror pictures, inverts the focus on American horror films (to which the picture sometimes refers) on the ‘bad patriarch’ and instead looks at the relationship between a mother and her daughter. The climax has a strong element of ambiguity that will resonate with first time viewers and ensure the film lingers in the memory. Perhaps most importantly, in terms of the film’s cache as part of the horror genre, the fright scenes are realised effectively, and it’s a very well-photographed film overall.

Arrow Video’s previous Blu-ray release of Dark Water was fine, perfectly serviceable, but this new 4k UHD release improves on it by no small amount. The disc contains the same contextual material as the previous Blu-ray release, but the presentation – based on the new 2023 4k restoration – improves on that release in a number of ways. More fine detail is present, but particularly noticeable is the improvement in the contrast levels provided by the HDR capabilities of the newer format. Compositions are also noticeably ‘opened up’ by more liberal framing. References: Balmain, Colette, 2008: Introduction to the Japanese Horror Film. Edinburgh University Press Lebeau, Vicky, 2008: Childhood and Cinema. London: Reaktion Books Newman, Kim, 2011: Nightmare Movies: Horror on Screen Since the 1960s. London: Bloomsbury (Revised Edition) Peirse, Alison, 2013: Korean Horror Cinema. Edinburgh University Press Scherer, Elisabeth, 2016: ‘Well-Traveled Female Avengers: The Transcultural Potential of Japanese Ghosts’. In: Braunlein, Peter J & Lauser, Andrea (eds), 2016: Ghost Movies in Southeast Asia and Beyond. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill: 61-82

|

|||||

|