|

|

The Film

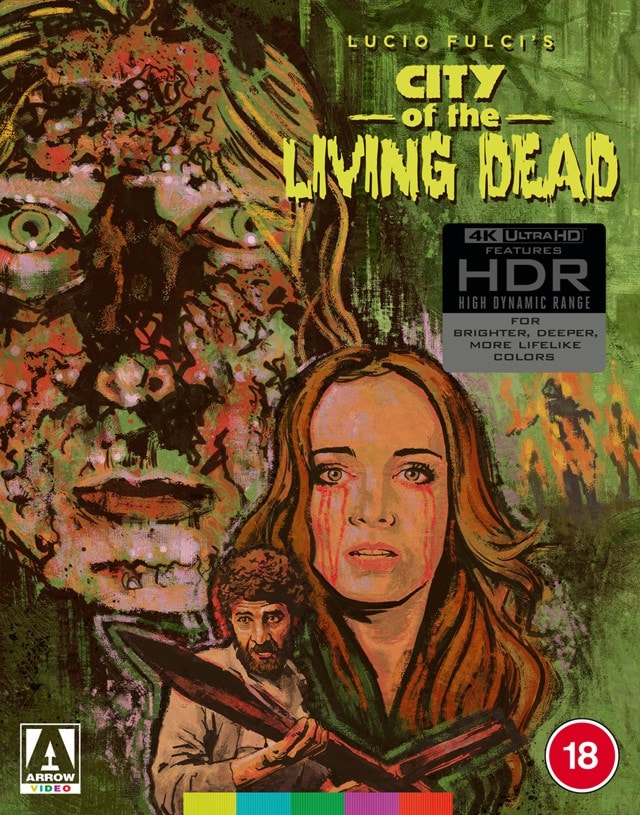

Paura nella citta dei morti viventi (City of the Living Dead, Lucio Fulci, 1980) Paura nella citta dei morti viventi (City of the Living Dead, Lucio Fulci, 1980)

In Dunwich, Father William Thomas (Davizio Jovine) hangs himself from a tree in the town’s churchyard. As a result of this unholy gesture, the dead rise from their graves. Meanwhile, in New York a séance is being held by Mary Woodhouse (Catriona MacColl), a psychic. During the séance, Mary experiences a vision of Father Thomas’ suicide. She screams and collapses, apparently dead. The police arrive; Detective Sergeant Clay (Martin Sorrentino) initially believes the séance to be a cover for a drugs den, until he and several other policemen witness flames which seemingly appear from nowhere. This strange event shakes their firm disbelief in the supernatural. Later, journalist Peter Bell (Christopher George) is investigating Mary’s presumed death when, in the cemetery, he hears noises emanating from Mary’s coffin, which is awaiting burial. Using a pickaxe, Peter smashes through the coffin lid and finds that, miraculously, Mary is still alive. Mary tells Peter of the apocalyptic events taking place in Dunwich, which have roots in an esoteric text, the Book of Enoch. Intending to find Dunwich before All Saints’ Day and close the gates of hell that have been opened by Father Thomas’ suicide, Mary and Peter make a frantic road trip. In Dunwich, therapist Gerry’s (Carlo De Mejo) meeting with his client Sandra (Janet Agren) is interrupted by Gerry’s lover Emily (Antonella Interlenghi). Emily tells Gerry that she plans to meet Bob (Giovanni Lombardo Radice), the local outcast for whom she feels some sympathy. However, Emily is killed by Father Thomas, who has been resurrected as a force of evil. When her body is discovered, the coroner suggests that Emily was literally frightened to death. Emily’s death is followed by that of young couple Tommy (Michele Soavi) and Rosie (Daniela Doria). Locals blame oddball Bob, who has been experiencing recurring visitations by the spectral Father Thomas. Eventually, Bob is lynched by a local man, who finds Bob in his garage with his teenaged daughter – and, in what is arguably the film’s most famous scene, kills Bob by pushing his head onto a drilling lathe.  Meanwhile, Emily returns as a zombie and slaughters her own parents in front of her young brother John-John (Luca Venantini). John-John is rescued by Gerry and Sandra, who have teamed up with Mary and Peter. As the supernatural events in Dunwich escalate, this small group of people strive to close the gates of hell before dawn breaks on All Saints’ Day. Meanwhile, Emily returns as a zombie and slaughters her own parents in front of her young brother John-John (Luca Venantini). John-John is rescued by Gerry and Sandra, who have teamed up with Mary and Peter. As the supernatural events in Dunwich escalate, this small group of people strive to close the gates of hell before dawn breaks on All Saints’ Day.

The second of the four zombie pictures that Lucio Fulci made in quick succession, City of the Living Dead followed Zombi 2/Zombie Flesh Eaters (1979) and preceded both L’aldila/The Beyond (1981) and Quella villa accanto al cimitero/The House by the Cemetery (1981). To some extent, Zombi 2 is the odd one out, with its Caribbean setting and focus on ‘daylight’ horror – in comparison with the increasingly Gothic texture of the subsequent entries in this (very) loose quartet of films. Philip L Simpson notes that the City of the Living Dead, The Beyond and The House by the Cemetery ‘are connected by the trope of hapless mortals literally living on top of an entrance to Hell and then inadvertently falling into it’ (Simpson, 2018: 246). They are also connected by the presence of Catriona MacColl in the leading female role, as well as a number of key personnel (including writer Dardano Sacchetti, editor Vincenzo Tomassi and cinematographer Sergio Salvati). As this group of films progressed, each subsequent narrative became less concrete, more illogical and dreamlike: Wheeler Winston Dixon has noted that ‘All of Fulci’s films progress as if the protagonists are trapped in some awful, illogical dream, from which there is no escape’ (Dixon, 2000: 73). Near the beginning of City of the Living Dead, for example, is a deeply atmospheric but utterly bizarre sequence in which Bob is shown entering a derelict house, where he finds a blow-up sex doll in a hearth and throws it against a wall, where it self-inflates. Bob approaches the doll and caresses it, but his attention is diverted by something else: what appears to be a rotting corpse which, judging by its size, is that of a child. It’s a sequence that has little relevance to the film’s overall narrative but which epitomises the dreamlike logic of City of the Living Dead.  Even the behaviour of the film’s zombies is highly illogical and inconsistent: in some moments, they are deeply corporeal – like the zombies in Zombi 2 – but in other scenes they seem to be ethereal, appearing and disappearing in the blink of an eye and via Méliès-style jump cuts. (In one scene late in the picture, it seems that Jerry has even discovered he can make the zombies disappear simply by closing his eyes and using the force of his will.) In some scenes, the zombies seem driven by a desire to consume human flesh; in other scenes, this seems not to be the case. And unlike Zombi 2 and The Beyond, the zombies aren’t the only ‘monsters’ in the picture: they are simply the most prominent symptom of the apocalyptic curse enacted by Father Thomas’ suicide, alongside a storm of maggots and other sundry manifestations of evil. The appearance of the zombies is accompanied by the spectral Father Thomas, who wordlessly drives these unearthly creatures on and causes other strange occurrences – including bleeding from the eye sockets and, in one case, a victim who vomits her internal organs. Even the behaviour of the film’s zombies is highly illogical and inconsistent: in some moments, they are deeply corporeal – like the zombies in Zombi 2 – but in other scenes they seem to be ethereal, appearing and disappearing in the blink of an eye and via Méliès-style jump cuts. (In one scene late in the picture, it seems that Jerry has even discovered he can make the zombies disappear simply by closing his eyes and using the force of his will.) In some scenes, the zombies seem driven by a desire to consume human flesh; in other scenes, this seems not to be the case. And unlike Zombi 2 and The Beyond, the zombies aren’t the only ‘monsters’ in the picture: they are simply the most prominent symptom of the apocalyptic curse enacted by Father Thomas’ suicide, alongside a storm of maggots and other sundry manifestations of evil. The appearance of the zombies is accompanied by the spectral Father Thomas, who wordlessly drives these unearthly creatures on and causes other strange occurrences – including bleeding from the eye sockets and, in one case, a victim who vomits her internal organs.

Like The Beyond and The House by the Cemetery, City of the Living Dead hints at forbidden arcane texts (where The Beyond has the Book of Eibon, City of the Living Dead has the Book of Enoch) attached to occult practices; in this sense, all three films owe a strong debt to the writings of H P Lovecraft. (The Beyond’s Book of Eibon took its name from a grimoire that featured in a number of Lovecraft’s stories, including ‘Dreams in the Witch-House’.) City of the Living Dead’s relationship with Lovecraft’s work is consolidated by the name of the small town in which Father Thomas commits suicide, Dunwich. For much of its running time, the film intercuts scenes set in New York with events taking place in Dunwich: the former is a rational space where the existence of the supernatural is doubted, whereas the latter is being invaded by supernatural entities and phenomena triggered by Father Thomas’ final act. ‘Ever since Father Thomas hanged himself, Dunwich ain’t been the same’, one of the locals observes, ‘It’s kind of scary’. Meanwhile, in New York Mary’s friend Theresa (Adelaide Asta) tells a disbelieving Detective Sergeant Clay that ‘At this very precise moment, in some other distant town, horrendously awful things are happening. Things that would shatter your imagination’.  Dunwich is haunted by its past: it is revealed that the town was built on the site of Salem, the film referencing the Salem witch trials; by committing suicide on hallowed ground, and in a way that is inspired by the Book of Enoch, Father Thomas has precipitated the apocalypse. (However, admittedly the film is unclear in its suggestion of whether or not these events are highly localised.) This is seemingly in revenge for the Salem witch trials that took place on the site almost three centuries earlier, the film’s confirmation of the supernatural offering an off-kilter validation of those witch trials. (The film’s focus on a community haunted by its past misdemeanours, and some of the events that take place later in the picture, invites comparison with John Carpenter’s The Fog, released earlier in the same year, and some of Stephen King’s later novels.) Bob, it seems, is chosen by Father Thomas as a conduit for some of the supernatural events because Bob’s mother was, in the words of Sandra, ‘a woman of easy virtue [….] Here in Dunwich, anyone like that is also branded a witch’. Elsewhere, the narrative logic falls apart when, during their hurried journey to find Dunwich before the eve of All Saints’ Day, Mary insists that she and Peter stop off for some food (‘Let’s go have a snack someplace’) – despite Theresa’s insistence that ‘if those gates [to hell] are left open it could be the end of humanity’ and ‘no dead body will be able to rest in peace again, and so the dead will rise up and take over the Earth’. Dunwich is haunted by its past: it is revealed that the town was built on the site of Salem, the film referencing the Salem witch trials; by committing suicide on hallowed ground, and in a way that is inspired by the Book of Enoch, Father Thomas has precipitated the apocalypse. (However, admittedly the film is unclear in its suggestion of whether or not these events are highly localised.) This is seemingly in revenge for the Salem witch trials that took place on the site almost three centuries earlier, the film’s confirmation of the supernatural offering an off-kilter validation of those witch trials. (The film’s focus on a community haunted by its past misdemeanours, and some of the events that take place later in the picture, invites comparison with John Carpenter’s The Fog, released earlier in the same year, and some of Stephen King’s later novels.) Bob, it seems, is chosen by Father Thomas as a conduit for some of the supernatural events because Bob’s mother was, in the words of Sandra, ‘a woman of easy virtue [….] Here in Dunwich, anyone like that is also branded a witch’. Elsewhere, the narrative logic falls apart when, during their hurried journey to find Dunwich before the eve of All Saints’ Day, Mary insists that she and Peter stop off for some food (‘Let’s go have a snack someplace’) – despite Theresa’s insistence that ‘if those gates [to hell] are left open it could be the end of humanity’ and ‘no dead body will be able to rest in peace again, and so the dead will rise up and take over the Earth’.

The highly ambiguous and often contradictory elements of the film’s plot are likely to be frustrating for some viewers, whilst for fans of Fulci’s vision they offer gory food for thought and have functioned as talking points amongst likeminded cinephiles for over three decades. Peter Hutchings has suggested that the vague plotting of Fulci’s zombie pictures is part of their charm, arguing that ‘The films’ narratives […] did not make a great deal of sense. Despite (or perhaps because of) this, Fulci managed to produce not just a series of remarkable set pieces but also an extraordinarily oppressive atmosphere’ (Hutchings, quoted in Simpson, 2018: 246). One of the film’s most impressively handled and atmospheric sequences is that in which Peter rescues Mary from her premature burial. Peter arrives at the cemetery and witnesses two workmen conversing over an opened grave that holds a skeletonised corpse which they are exhuming. These men are blasé about their task and display a lack of hurry in burying Mary’s coffin. Peter stands next to Mary’s coffin as Fulci cross-cuts between Peter, in the cemetery, and the inside of the coffin. Mary awakens and gasps for air, her breath causing condensation on the mirror fastened to the inside of the coffin lid. Hearing her movement inside the coffin, Peter grabs a pickaxe and uses it to break through the coffin lid; with each blow, the blade of the pickaxe narrowly misses Mary’s face. It’s a tense sequence which has several corollaries in Fulci’s other zombie pictures: for example, Mrs Menard’s face being dragged towards the splintered door in Zombi 2; and Dr Freudstein pushing Bob’s face against the cellar door as Bob’s father uses an axe to try to break the door down.  As with Fulci’s other zombie pictures, City of the Living Dead marries Gothic stylings (a journey into an underground crypt, complete with skeletons falling through the earth above the protagonists’ heads) with graphic gore. UK horror fans who first encountered the film at the cinema or via its VHS releases will remember the almost feverish discussions about the gruesome footage cut from City…, not to mention Fulci’s other zombie pictures, by the BBFC during the 1980s. Wheeler Winston Dixon wrote of The Beyond that Fulci’s ‘slight framing narrative is merely the excuse for Fulci to stage a series of macabre, distressing set pieces’, and the same has been said of City of the Living Dead (Dixon, 2000: 74). (The special makeup effects in City… were not by Giannetto De Rossi, the artisan behind the makeup effects of Fulci’s three other zombie pictures, but were supervised by Gino De Rossi, whose work displays an emphasis on prosthetics.) The UK cinema release omitted the moment in which a lathe is driven through Bob’s head by the irate father of a teenaged girl, but subsequent video releases featured even more cuts – to the scene in which Daniela Doria’s character vomits up her intestinal tract, and three scenes in which zombies rip the brains from their victims’ skulls. However, as with many cuts made by the BBFC during this era, the removal of footage from these scenes arguably had the opposite of the intended effect, increasing their impact and made them more traumatic for the audience: in the film’s uncut version, the gore scenes are extended to the point that they become absurd and almost blackly comic. (This is particularly true of the aforementioned scene in which Daniela Doria’s character vomits ad nauseam – if you’ll pardon the pun – with Fulci cutting from the actress’ face to a tight close-up of the mouth of a prosthetic head, great wads of offal being pushed through the opening.) One particular scene in City of the Living Dead seems to function as a metonym for Fulci’s fascination with thrusting the abject into his audience’s collective face: when Father Thomas appears before Emily, he grabs a handful of dirt and worms, rubbing this matter into the face of the traumatised Emily. As with Fulci’s other zombie pictures, City of the Living Dead marries Gothic stylings (a journey into an underground crypt, complete with skeletons falling through the earth above the protagonists’ heads) with graphic gore. UK horror fans who first encountered the film at the cinema or via its VHS releases will remember the almost feverish discussions about the gruesome footage cut from City…, not to mention Fulci’s other zombie pictures, by the BBFC during the 1980s. Wheeler Winston Dixon wrote of The Beyond that Fulci’s ‘slight framing narrative is merely the excuse for Fulci to stage a series of macabre, distressing set pieces’, and the same has been said of City of the Living Dead (Dixon, 2000: 74). (The special makeup effects in City… were not by Giannetto De Rossi, the artisan behind the makeup effects of Fulci’s three other zombie pictures, but were supervised by Gino De Rossi, whose work displays an emphasis on prosthetics.) The UK cinema release omitted the moment in which a lathe is driven through Bob’s head by the irate father of a teenaged girl, but subsequent video releases featured even more cuts – to the scene in which Daniela Doria’s character vomits up her intestinal tract, and three scenes in which zombies rip the brains from their victims’ skulls. However, as with many cuts made by the BBFC during this era, the removal of footage from these scenes arguably had the opposite of the intended effect, increasing their impact and made them more traumatic for the audience: in the film’s uncut version, the gore scenes are extended to the point that they become absurd and almost blackly comic. (This is particularly true of the aforementioned scene in which Daniela Doria’s character vomits ad nauseam – if you’ll pardon the pun – with Fulci cutting from the actress’ face to a tight close-up of the mouth of a prosthetic head, great wads of offal being pushed through the opening.) One particular scene in City of the Living Dead seems to function as a metonym for Fulci’s fascination with thrusting the abject into his audience’s collective face: when Father Thomas appears before Emily, he grabs a handful of dirt and worms, rubbing this matter into the face of the traumatised Emily.

As in some of his other films, Fulci is also unafraid of placing child characters in extreme danger, something which seems anathemic to the sensibilities of Hollywood films. In City of the Living Dead, Emily’s young brother John-John (named Johnny in the Italian version of the film) witnesses the brutal murder of his parents by his zombiefied sibling. Interestingly, Fulci chooses not to show the aftermath of this event, referencing it obliquely by a bloodstain on the ceiling of the room in which Gerry finds John-John, John-John’s parents’ blood soaking through the floor of the room upstairs.  Alongside the memorably graphic gore scenes and bizarre, dreamlike narrative, City of the Dead contains some outrageous dialogue: when Sandra asks Gerry, ‘Do you consider me a basket case?’, he answers by telling her ‘You’re nurturing a neurosis, that’s all. Like about 70 per cent of the female population of this country’. There seems to be something intentionally off-key about Gerry’s relationship with Emily too: Emily is clearly either an older teenager or just out of her twenties (Antonella Interlenghi would have been 19 when the film was lensed), whereas Gerry is quite obviously in his mid/late thirties. Their relationship is placed in relief against the treatment of Bob, who Emily describes as a ‘kid’ but, as played by Giovanni Lombardo Radice, is noticeably older than Emily herself. (Radice is six years the senior of Interlenghi, and this shows onscreen.) However, Bob is effectively lynched by a local who catches Bob with his daughter – who offers the childlike Bob a hit on a marijuana joint – and assumes that Bob, a harmless oddball, is some kind of potentially violent sexual predator. One might wonder if, in his exploration of this minor theme within the picture, Fulci and Dardano Sachetti were influenced by the treatment of David Warner’s character in Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1972). The murder of Bob is arguably the most gruesome and memorable setpiece in the picture, and it seems obviously intentional that the cruellest moment within the picture has nothing to do with the supernatural and everything to do with man’s cruelty to his fellow man – a theme also hinted at by the treatment of the warlock Shweik in the pre-credits sequence of The Beyond and explored elsewhere in Fulci’s body of work (the chain-whipping of the witch in Don’t Torture a Duckling, and throughout Fulci’s 1969 adaptation of Antonin Artaud’s play Beatrice Cenci). Alongside the memorably graphic gore scenes and bizarre, dreamlike narrative, City of the Dead contains some outrageous dialogue: when Sandra asks Gerry, ‘Do you consider me a basket case?’, he answers by telling her ‘You’re nurturing a neurosis, that’s all. Like about 70 per cent of the female population of this country’. There seems to be something intentionally off-key about Gerry’s relationship with Emily too: Emily is clearly either an older teenager or just out of her twenties (Antonella Interlenghi would have been 19 when the film was lensed), whereas Gerry is quite obviously in his mid/late thirties. Their relationship is placed in relief against the treatment of Bob, who Emily describes as a ‘kid’ but, as played by Giovanni Lombardo Radice, is noticeably older than Emily herself. (Radice is six years the senior of Interlenghi, and this shows onscreen.) However, Bob is effectively lynched by a local who catches Bob with his daughter – who offers the childlike Bob a hit on a marijuana joint – and assumes that Bob, a harmless oddball, is some kind of potentially violent sexual predator. One might wonder if, in his exploration of this minor theme within the picture, Fulci and Dardano Sachetti were influenced by the treatment of David Warner’s character in Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1972). The murder of Bob is arguably the most gruesome and memorable setpiece in the picture, and it seems obviously intentional that the cruellest moment within the picture has nothing to do with the supernatural and everything to do with man’s cruelty to his fellow man – a theme also hinted at by the treatment of the warlock Shweik in the pre-credits sequence of The Beyond and explored elsewhere in Fulci’s body of work (the chain-whipping of the witch in Don’t Torture a Duckling, and throughout Fulci’s 1969 adaptation of Antonin Artaud’s play Beatrice Cenci).

Video

This is Arrow Video’s third go-round with City of the Living Dead, which they have previously distributed via two separate Blu-ray releases. As with those releases, this presentation of the film is uncut, with a running time of 92:52 mins. This is Arrow Video’s third go-round with City of the Living Dead, which they have previously distributed via two separate Blu-ray releases. As with those releases, this presentation of the film is uncut, with a running time of 92:52 mins.

On Arrow’s new 4k UHD release, Fulci’s film is presented in 2160p and in Dolby Vision (HDR10 compatible), using the 1HEVC codec. The presentation uses the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The presentation is based on a restoration, from a 4k scan of the original camera negative, conducted by Cauldron Films, who have released the film in 4k in the US. There is some debate as to the format in which City of the Living Dead was photographed. For a number of years, some quarters suggested the film was shot in 16mm and blown-up to 35mm for cinema exhibition. Meanwhile, some sources (principally, Blue Underground’s Bill Lustig) suggest the picture was photographed in Techniscope, the 2-perf 35mm format, presumably in order to save on negative and shipping costs, and then cropped in postproduction to 1.85:1. Other sources have suggested that the picture was shot in a 3-perf format, however unlikely this seems – given that 3-perf formats didn’t become a prevalent ‘thing’ within filmmaking until around 1986, when Rune Ericson shot Pirates of the Lake using Panaflex cameras specially modified to shoot 3 perforations per frame, preceding the use of 3-perf formats in the US television industry and the introduction of the Super 35 format. Regardless, the film is the only one of Fulci’s zombie films not to be presented in a ‘scope ratio: Zombi 2, The Beyond and The House by the Cemetery were all shot in 2-perf Techniscope and presented at cinemas in the 2.35:1 screen ratio.  Whichever format the picture was shot in, the result was a film that has a very coarse grain structure. This was exacerbated by the fact that much of the film seems to have been shot on very fast film stocks, presumably to better accommodate the many low-light scenes. The lenses used on the picture don’t seem to have been the best, optically speaking; it looks like some shots suffer from focus shift in the lenses – or perhaps the rushed production and low-light nature of many of the scenes necessitated the use of wide apertures resulting in some shots seeming to be slightly out of focus. Whichever format the picture was shot in, the result was a film that has a very coarse grain structure. This was exacerbated by the fact that much of the film seems to have been shot on very fast film stocks, presumably to better accommodate the many low-light scenes. The lenses used on the picture don’t seem to have been the best, optically speaking; it looks like some shots suffer from focus shift in the lenses – or perhaps the rushed production and low-light nature of many of the scenes necessitated the use of wide apertures resulting in some shots seeming to be slightly out of focus.

With those general observations vis-à-vis the screen format and lensing of the picture out of the way, it’s worth noting that Arrow’s previous Blu-ray release of the film was very good. This new 4k presentation is even better. The presentation is organic and filmlike, retaining the structure of 35mm film; the often coarse grain structure is present throughout the film, particularly evident in lowlight scenes, and carried excellently by the encoded to disc. Colours are accurate, with a palette that is dominated by lots of earthy browns and greens, along with muted skintones that are offset by bursts of grue. The 4k UHD upgrade noticeably improves on the previous HD Blu-ray release in the area of contrast levels, and again this is most noticeable in the film’s many low-light scenes which depict dark, cavernous interiors – with surfaces of stone or wood picked out by reflected light. (The climax, which takes place beneath the cemetery and in the titular “city of the living dead,” exemplifies this; as does the scene in which Mary is depicted buried alive within her coffin, soft blue light quietly catching the texture of her face and clothing.) There’s much use of backlights on the actors, and highlights have nuance, depth, and texture to them – even in high contrast scenes, such as the moment in which bursts of flame suddenly appear in the psychic medium’s abode following Mary’s “death.” Midtones also have depth texture and clarity to them, and are rich in definition. Shadows are deep, and the exposure tapers off with some subtle gradation into the toe – so when Bob lifts his blow-up sex doll out of the dark fireplace at the abandoned house, the appearance of the doll’s face is comically abrupt/surprising. In all, it’s an excellent presentation of the film, comparable to the 4k release from Cauldron Films in the US. (Both are based on the same restoration, but obviously with unique – seemingly equally robust – encodes.)

Audio

The disc presents the viewer with several audio options: (i) the original English mono mix (as a DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 track); (ii) a stereo mix (as a DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 track); (iii) DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 ‘upmix’; and (iv) the Italian mono mix (DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0). The English tracks are accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing; the Italian track is accompanied by English subtitles translating the Italian dialogue. (These are again optional.) All of the audio tracks are fine. The 5.1 mix feels a little dissipated and anaemic in comparison with the English mono and stereo tracks, with the stereo mix offering a good balance of clarity and atmospheric sound separation. Of the mono tracks, the Italian track feels a little flat in direct comparison with the English track: it’s muffled and “tinny”/thin – like being underwater – but its inclusion is to be applauded, and the Italian dialogue is subtly different in many places from the dialogue in the English version of the film.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary by Catriona MacColl and Jay Slater. This audio commentary first appeared on the Vipco DVD release of the film and features MacColl reflecting on her role in this film and Fulci’s other pictures. She reveals why on this picture she is credited as ‘Katriona MacColl’ and as ‘Katherine MacColl’ in her other roles for Fulci – because her Italian agent told her that her name translated as ‘Big Huge Catherine’ for Italian audiences. MacColl talks about her work in what she calls ‘Europuddings’ and reflects on her relationship with Fulci in this and the other zombie films on which they collaborated. - A second audio commentary with Giovanni Lombardo Radice and Calum Waddell. This commentary appeared on Arrow’s previous Blu-ray release and features Radice, aka John Morghen, on fine form. He reflects on his roles in Fulci’s films and talks about the work of the other cast members involved in the film. It’s a fast-moving track with plenty of first-hand insight into this period of Italian filmmaking. - ‘We are the Apocalypse’ (53:02). This exhaustive new interview with writer Dardano Sacchetti looks back on Sacchetti’s work with Fulci, who Sachetti describes as ‘a bastard, from every point of view’ but ‘a great craftsman, an excellent mercenary and showman, an excellent director’. Sacchetti offers some fascinating insight into the writing of these films, exploring some of their relationships with the work of writers like Lovecraft and considering how the scripts evolved through Sacchetti’s interactions with Fulci. The interview is in Italian and accompanied by optional English subtitles. - ‘Through Your Eyes’ (37:03). Catriona MacColl is interviewed about her work on City of the Living Dead, discussing how she came to be cast in the picture and reflecting on some of the more challenging aspects of the shoot (particularly the scene in which MacColl, George, De Mejo and Agren are drenched in maggots).

- ‘Dust in the Wind’ (13:13). Camera operator Roberto Forges Davanzati talks about his career in the Italian film industry. He discusses the challenges involved in lighting for cinema, and suggests the most ‘straightforward’ approach is the best. Davanzati reflects on Fulci’s reputation for being ‘grumpy’ and his oft-discussed disregard for actors, but Davanzati discusses the maestro with a strong sense of fondness. The interview is in Italian and accompanied by optional English subtitles. - ‘The Art of Dreaming’ (45:52). Massimo Antonello Geleng, the production designer on the picture, talks about working with Fulci on a number of pictures, praising in particular Fulci’s adaptation of Beatrice Cenci. Geleng discusses the challenges he faced in shooting in the town of Savannah, Georgia, which he suggests was not right for the tone of the film. (The film should have been shot ‘somewhere north of New York’, Geleng argues.) The interview is in Italian and accompanied by optional English subtitles. - ‘Tales of Friendship’ (30:51). Cinematographer Sergio Salvati discusses his work on City of the Living Dead. Salvati talks about his long-standing working relationship with Fulci. In contrast with Geleng, Salvati praises Savannah, Georgia, as a ‘wonderful location’ for the film. He discusses Fulci’s approach to directing films, highlighting Fulci’s technical knowledge and his ability to liaise with various members of the crew. Salvati also talks about working with the various members of the cast, and reflects on Fulci’s reputation for tormenting his actors. The interview is in Italian and accompanied by optional English subtitles.

- ‘I Walked with a Zombie’ (22:51). Giovanni Lombardo Radice talks about his work with Fulci, reflecting on Fulci’s dissatisfaction with the fact that in Italy, he was regarded as a director of what were considered ‘B’ movies. Whilst Fulci’s decision to make horror movies was dictated by market trends, Radice suggests he did this ‘in the best possible way’ although Fulci himself was not a fan of horror pictures. Radice reflects in detail about how the effect with the drilling lathe was achieved. The interview is in Italian and accompanied by optional English subtitles. - ‘They Call Him “Bombardone”’ (26:57). Gino De Rossi discusses the effects of City of the Living Dead, commenting on how he came to work with Fulci and suggesting that Fulci had an undeserved reputation for being difficult or ‘grumpy’. De Rossi laments that the days of directors like Fulci have passed, and he discusses some of the specific effects used in City…. The interview is in Italian and accompanied by optional English subtitles. - ‘The Horror Family’ (19:16). Interviewed separately, actors Venantino Venantini and Luca Venantini, father and son, discuss their work on the film. (Venantino played one of the men in the roadside bar, and Luca essayed the role of John-John.) Luca talks about the memorable ending of the picture and discusses his reactions, as a child actor, to some of the more frightening scenes in the film. Venantino comments on Fulci’s reputation and skill, and discusses his surprise at the popularity his films with Fulci have overseas, particularly in the US. The interviews are in Italian and accompanied by optional English subtitles. - ‘Songs from Beyond’ (19:49). In an archival interview, Fabio Frizzi talks about his work with Fulci and reflects on the processes by which he wrote the music for the Fulci pictures on which he worked. The interview is in Italian and accompanied by optional English subtitles.

- ‘Building Fulci’s City’ (37:34). Stephen Thrower offers an impassioned appraisal of City of the Living Dead, discussing the film’s literary antecedents and considering City…’s position within Fulci’s other horror pictures. - ‘Reflections on Fulci’ (26:50). This is another appraisal of Fulci’s horror films by yet another notable super-fan of the picture, filmmaker Andy Nyman. Nyman talks about his first experience with Fulci’s films, via a viewing of The Beyond on VHS – suggesting that what he finds interesting about Fulci’s films is the ‘striking visuals, amazing setpieces’ that are juxtaposed with crude filmmaking techniques. - ‘The Dead are Alive!’ (25:26). Journalist Kat Ellinger narrates a video essay which situates City of the Living Dead within the paradigms of post-Night of the Living Dead (Romero, 1968) zombie pictures. - ‘Behind the Fear’ (10:38). Some fascinating 8mm footage of the production is presented with commentary from camera operator Roberto Forges Davanzati. Davanzati speaks in Italian, and optional English subtitles are provided. - Archival Special Features: Introduction by Carlo de Mejo; ’Fulci in the House’ – an appreciation of Fulci’s work by filmmaking peers(18:35); ‘Carlo of the Living Dead’ (18:13); ’Dame of the Dead’ – interview with Catriona MacColl (25:55); ’Fulci’s Daughter’ – an interview with Antonella Fulci(28:44); ’Penning Some Paura’ – an interview with screenwriter Dardano Sacchetti (18:59); ’Profondo Luigi’ – an interview with Luigi Cozzi (17:43); Live from the Glasgow Film Theatre; The Many Lives of Giovanni Lombardo Radice – an (excellent) documentary looking at the career of Radice/’John Morghen’ (52:36). - Alternative US Opening Titles (2:20). These are the ‘Gates of Hell’ titles from the US version of the picture. - Original Trailers and Radio Spots: UK Trailer (3:03); Italian Trailer (3:05); The Gates of Hell TV Spot (0:32); Radio Spots (0:57). - Image Gallery: Stills (40 images); Posters and Press (18 images); Lobby Cards (59 images); Home Video and Soundtrack Sleeves (26 images).

Overall

It’s difficult not to be partisan about Fulci’s horror films, one way or the other, as they are so incredibly divisive. The dreamlike logic and the emphasis on the electrocardiogram thrill either works for the viewer or it doesn’t. The interview with Andy Nyman on this disc is very interesting, in the sense that Nyman foregrounds the contrast within Fulci’s horror films between some incredible artistry (the cinematography and lighting of the horror sequences; the set design; the brave disregard for conventional plotting) with the crudity of some of the techniques on display and their emphasis on the abject – the manner in which they wallow in the idea of death and decay, arguably more so than most zombie films. Nyman’s comments get at the heart of the appeal of these films. Like many British horror film fans whose formative experiences took place during the early VHS era, Fulci’s zombie pictures made an incredible impact on myself when I first saw them as a child via their videocassette releases, and they have stayed with me ever since. Though The Beyond remains my favourite of Fulci’s zombie films, City of the Living Dead is an incredible experience. It’s difficult not to be partisan about Fulci’s horror films, one way or the other, as they are so incredibly divisive. The dreamlike logic and the emphasis on the electrocardiogram thrill either works for the viewer or it doesn’t. The interview with Andy Nyman on this disc is very interesting, in the sense that Nyman foregrounds the contrast within Fulci’s horror films between some incredible artistry (the cinematography and lighting of the horror sequences; the set design; the brave disregard for conventional plotting) with the crudity of some of the techniques on display and their emphasis on the abject – the manner in which they wallow in the idea of death and decay, arguably more so than most zombie films. Nyman’s comments get at the heart of the appeal of these films. Like many British horror film fans whose formative experiences took place during the early VHS era, Fulci’s zombie pictures made an incredible impact on myself when I first saw them as a child via their videocassette releases, and they have stayed with me ever since. Though The Beyond remains my favourite of Fulci’s zombie films, City of the Living Dead is an incredible experience.

Arrow Video’s new 4k UHD release of City of the Living Dead is excellent. The presentation of the film – identical in its source to Cauldron Film’s US release – is superb, easily eclipsing the film’s previous Blu-ray releases. There is an astonishing array of contextual material, and regarding this, the word “exhaustive” comes to mind. UK fans of Fulci’s horror films will find this release to be an essential purchase, alongside Arrow Video’s recent 4k UHD release of Fulci’s The House by the Cemetery. References: Dixon, Wheeler Winston, 2000: The Second Century of Cinema: The Past and Future of the Moving Image. State University of New York Press Simpson, Philip L, 2018: ‘“No one who sees it lives to describe it”: The Book of Eibon and the Power of the Unseeable in Lucio Fulci’s The Beyond’. In: Miller, Cynthia J & Van Riper, A Bowdoin, 2018: Terrifying Texts: Essays on Good and Evil in Horror Cinema. London: McFarland: 245-54

|

|||||

|