|

|

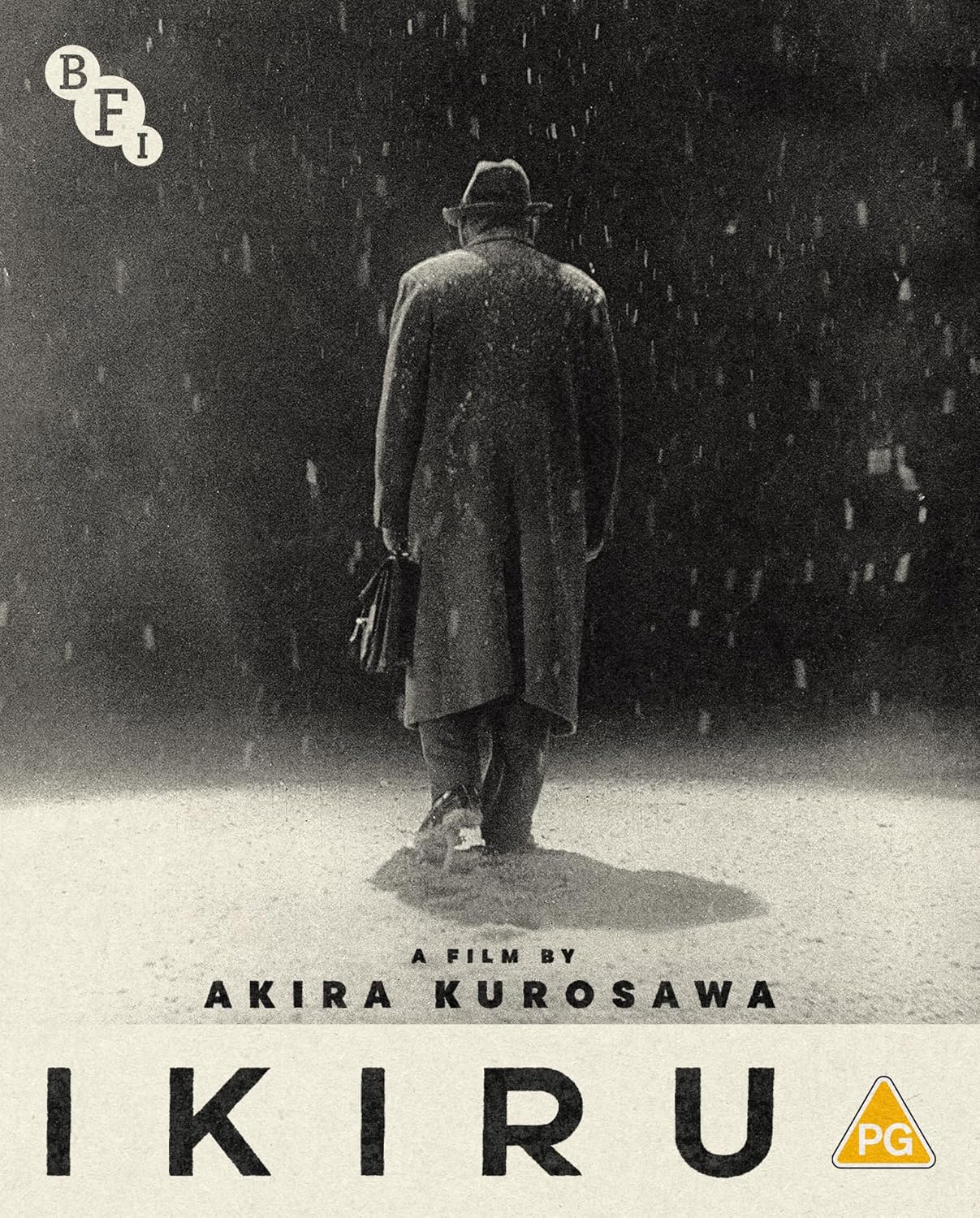

Ikiru

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - British Film Institute Review written by and copyright: James-Masaki Ryan (18th August 2024). |

|

The Film

"Ikiru" 「生きる」 (1952) Watanabe Kanji (played by Shimura Takashi) has worked at the local city hall for the last thirty years with perfect attendance. When he discovers that he has terminal stomach cancer with only a few months to live, it sends him into depression and panic, as he realizes that he has never truly "lived" for all this time. He has a distant relationship with his adult son Mitsuo (played by Kaneko Nobuo) even though they live in the same home. Kanji's wife passed away when Mitsuo was young and his life has been in a sad state ever since with the repeated tasks of remedial work at city hall every day and without any hobbies or friends to interact with. But with his limited time left, he is determined to find some purpose to his life. Filmmaker Kurosawa Akira had a simple concept of a story about a man with 75 days left to live. He along with screenwriter Hashimoto Shinobu brainstormed ideas on what kind of man the story would be about and how the story would unfold, but it was when friend and screenwriter Oguni Hideo stepped in, the story would change direction. Instead of ideas such as having someone powerful or lively suddenly being afflicted with cancer, they decided to go with something less exciting with a man that is a nobody and has an awakening. In addition, Oguni suggested that the character's death would not be the end of the story, but the story could continue after his passing with the legacy he leaves behind. The opening of "Ikiru", which literally means "to live", starts unconventionally with an X-ray of the protagonist's cancer afflicted lungs, showing his shortened lifeline before the actual character is introduced. From there the audience is shown his job as a deputy clerk at a city hall with stacks and stacks of paper on the desks and behind the workers, showing there is a lot of work to be done but also at how backed up things are. At the same time it also shows the inefficiency of the city hall, as people get passed from department to department and paperwork moves extremely slowly, which is sadly not too different from how city hall offices operate in Japan today. The film does an excellent job of showing the inefficiency, with the surrounding workers seemingly doing the bare minimum at their desks, and also a great montage sequence with the famed "Kurosawa wipes" going from one department to the next as the workers are reluctant to take the jobs on themselves. Shimura as Watanabe Kanji is always hunched over his desk of seemingly endless piles of paper and he is buried within his work. But he doesn’t work efficiently with pleasure, nor does he have anxiety or frustration either. It’s just a mindless office job that doesn’t seem to require much skill or talent, and it’s just what he has been doing for many years without much thought. In addition to that, Kanji is a widower and lives with his adult son, and their relationship is a strained one. From losing his wife, having to raise a son as a single father, making ends meet with a remedial job, and also experiencing the trauma of the country at war just a decade ago, the stress of life itself is just as stacked as the papers on his work desk. To make things even worse, he learns that he has terminal cancer and only has a few months to live. He speaks with a frail and quiet voice as if he is always out of oxygen, has a resting face of sadness as if he hadn’t smiled in decades, and moves just as slowly as the legislation of his city hall. Shimura’s performance brings tears to viewers from the start, as so much is conveyed in his physical demeanor, his raspy voice, and his face that is heavy with emotional weight. It is a far cry from the cowardly woodcutter he portrayed in “Rashomon” a few years prior or as the gracefully powerful yet friendly leader Shimada Kanbei in “Seven Samurai” a few years later. Production started on March 14th, 1952, which was two days after Shimura celebrated his 47th birthday, though he would be portraying a man at least a decade older for the film. Prior to production, Shimura had surgery for appendicitis which made him lose some weight. Kurosawa suggested for him to keep his thinner figure, and Shimura started frequenting a sauna for the role. Kanji's transformation starts off with him withdrawing Ą50,000 from the bank and seeing if he could spend it by having fun on a night in Tokyo. Unfortunately he doesn't know how to, which leads to his encounter with a novelist (played by Ito Yunosuke who shows him what the nightlife is like. From pachinko parlors, dancehalls, strip shows, and drinking all night, none of it gives Kanji the satisfaction he desires. Kurosawa and his crew showcase an enhanced and lavish version of the nightlife in postwar Tokyo with beautiful clubs, wall to wall people dancing, and beautiful young women at every corner looking for a good time. There are some great visual tricks with mirrors doubling sizes of locations, the choreography of the actions and the camerawork, as well as with audio by overlapping music cues and crowd noise for a bustling environment throughout the night. It is also notable for the singing sequence, in which Kanji tearfully sings the 1920s Japanese hit "Song of the Gondola" in a haunting and sad way. What invigorates Kanji is the following day when he runs into his subordinate Toyo (played by Odagiri Miki). She finds the work at city hall to be constrictive and asks him for approval for her resignation. She is the exact opposite of Kanji, as she is constantly on the move, smiling, talkative, and incredibly positive, and this makes Kanji feel as if she is the missing key to his life - by being inspired to feel joy. Unfortunately as they continue to meet, it causes friction with Kanji's son and his daughter-in-law Kazue (played by Seki Kyoko) and their housemaid (played by Minami Yoshie) who think he is in a relationship with her and spending his money. Although he realizes that just spending time with Toyo is not the answer he is looking for, she becomes the catalyst for his eventual change, as it gives him the energy to use his power at his workplace to actually get something done. In this case, it is to get the paperwork through to build a park on a derelict site for the neighborhood children. Born on March 12th, 1905 in Hyogo, Japan, Shimura Takashi's birth name was Shimazaki Shoji. Turning to acting while he was a university student, he changed his name to Shimura Takashi for the stage. He worked on stage and in radio before he signed with Shinko Kinema company in 1934, where he debuted in the film “Number One, Love Street” that year in a small role. Though he had a commanding voice, it was ironic that his screen debut was a silent film. His voice would be first heard on film in his fourth feature, “Chuji Makes a Name for Himself” in 1935, which is unfortunately considered lost. For the rest of the decade and into the war years, Shimura worked consistently on screen in various genres from modern day dramas to period samurai films. He even appeared in the period musical "Singing Lovebirds" in 1939 where he displayed his singing abilities for the first time. It was said that musician and co-star Dick Mine (who was born Mine Tokuichi and used a western stage name) was so impressed that he urged Shimura to consider a singing career, which never came to fruition. Even with over a hundred screen credits by the next decade, he was never a lead performer, with all of his roles being a supporting player. Being in his thirties and not having the look of a leading man, he wasn’t exactly bankable to filmgoers, though he was a respected performer in the business. Following his work on films for Shinko Kinema, as well as for studios Makino Talkie KK, Nikkatsu, and Shochiku, he signed with Toho Studios in 1943, and it was from there that his film career seriously took greater notice. His first film at the studio was the directorial debut of Kurosawa Akira in the judo biopic “Sugata Sanshiro” in a supporting role. He would become Kurosawa’s most frequently cast actor with 21 appearances, and it was Kurosawa that gave Shimura some of his biggest roles, such as playing straight detectives in "Drunken Angel" (1948) and “Stray Dog” (1949), the father doctor in “The Quiet Duel” (1949), a lowly lawyer in “Scandal” (1950), and the bumbling yet frightened woodcutter in “Rashomon” (1950). He played men with great dignity, hard boiled yet wise cops, poor lower class figures, and many more showcasing his range with his acting skills, especially through his voice, changing tone and mannerisms from character to character. But with Kurosawa’s casting of Shimura in “Ikiru” in 1952, it would be a role that was emotionally more demanding than anything he had ever done, and in the leading role no less. With production lasting a very lengthy six month period, Shimura brought life into a character that was basically lifeless through a restrained performance of a physically and emotionally broken man. The change in his stature and expression when he solemnly sings “Song of the Gondola” at the bar and later on the swing in the snow showcases Shimura’s brilliance as a performer. A far cry from his bravado singing ability as seen in “Singing Lovebirds”, the emotional cry in his singing voice in “Ikiru” is truly heartbreaking. While he is also remembered for many other performances including a number of "Godzilla" and related kaiju films, the "Tora-san" series, and further works with Kurosawa, his performance in “Ikiru” is a true standout. In 1974, he was awarded the Medal with Purple Ribbon from the Japanese government for his contributions as an actor for the arts, which was given while he was hospitalized and diagnosed with emphysema. Like the character of Watanabe Kanji, the diagnosis did not slow him down as he continued to work on screen in film and on television, but his health was deteriorating. From 1977 onward he was frequently in and out of hospital, and one of his final appearances on screen was in Kurosawa’s “Kagemusha” in 1980 for a small cameo appearance that was unfortunately one of the scenes trimmed for the international release. At 10:41AM on February 11th, 1982, Shimura passed away from emphysema complications at the age of 76. He was survived by Masako, his wife of 44 years who passed away in 2005. Odagiri Miki was born Santo Miki on June 29th, 1930. She was a child actress, debuting on stage in 1935 with Shinkyogekidan troupe and made her film debut in 1938 with "Pastoral Symphony" under her stage name Fujiyama Kimiko. She also continued on stage and made a few appearances on film during her childhood years, but her film debut as an adult came with "Ikiru" when she was a student at the Haiyuza Theatre Company. As a first year student, she was not allowed to go to auditions for outside work, but she broke the rule for a chance to be in a Kurosawa directed film and attended the audition for the role of Toyo along with her senior classmate, actress Iwasaki Kaneko. Kurosawa picked her from the hundreds of young actresses that auditioned as he felt something special from her. But she stated that it was an extremely difficult role to play. She was told to frequently move around even in closeups and not to worry about going in and out of frame. This created a a childlike presence for her character, always a contrast to the frozen character of Kanji. In 1993, Odagiri recalled about some on set problems, including many instances of her making mistakes with the dialogue and missing her marks causing Kurosawa to yell at her many times in furor. There was also an incident during production in which she got into a physical argument with her then boyfriend and later husband Yasui Shoji which led to her having an injury on her nose. She was scheduled to shoot the scene in which Toyo visits Kanji's home for his stamp of approval, but Kurosawa was furious with her for her appearance. Luckily, the injury was covered by the make-up artist and it went unnoticed by audiences. There was also a scene in which the character had to eat oshiruko, a Japanese dessert which Odagiri hated in real life and was again scolded by Kurosawa to do retakes until she could act and show that it looked delicious. Even with the constant yelling by the director and shedding a lot of tears, she stated that Shimura was very supportive of her and gave her the encouragement to do her best. While the experience seemed harsh and traumatic, the young actress took it to inspiration, and renaming herself Odagiri Miki, with the surname Odagiri coming from the character of Toyo's surname. She recalled that after the film's first screening in Hibiya, she was so pleased and amazed at the film and how she was able to be part of something so wonderful. After the screening and event was over, she was in such a jovial and uplifting mood that she decided to walk all the way home from the theater a full seven kilometers while thinking about how beautiful the film was. Following "Ikiru", Odagiri continued acting in film and in television in the 1950s. With her marriage to Yasui, the couple had two daughters - Yomo Masami born in 1953 and Yomo Harumi born in 1957. Both children became child actors and notably in 1966 Harumi was cast in the television series "Chako-chan" in the lead, with her parents being played by her real life parents. During the 1960s, Odagiri concentrated more on television and stage than in film. She was absent from screens in the 1970s but made some occasional appearances on television dramas in the 1980s. She retired after having a role in the 1987 film "Shinran: Path to Purity", but remerged in 2003 when she made an appearance in the documentary "It Is Wonderful to Create" for the "Ikiru" DVD release, as well as returning to stage for "Siberian Express 4" the same year. Although "Ikiru" would be the only appearance she made in a Kurosawa film and it was not the most pleasant experience for her, she always felt that the experience was like a treasure to her. She died on November 28th, 2006 from heart failure. Kurosawa came face to face with death when he witnessed the destruction from the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. His dear older brother Heigo committed suicide in 1933. He was not conscripted, though he saw war firsthand through air raids across during World War II. Death was always a step away from him at some point, and the film was in a way about turning his fear of it into something positive. But the first cut of the film left him questioning if he had made a mistake as it lacked the emotional depth that such a story required. It was not the fault of the performances or the visuals, but he felt that the score cues composed by Hayasaka Fumio was unfortunately getting in the way of the performances. In a difficult decision, Kurosawa decided to remove most of the music cues, and leave only a few intact. Even with those composed cues removed, there are a lot of important cues to be heard. In addition to "Song of the Gondola" which plays at both the saddest and the happiest moments for Kanji, there is also the "Happy Birthday" song that plays when Kanji realizes his destiny as it also plays in the background when he returns to the city hall to start his work on the park. Although Hayasaka was initially disappointed with the decision to leave out many of his compositions, the relationship with Kurosawa was not strained, as they would work together on Kurosawa's next film "Seven Samurai" in 1954 and for "I Live in Fear" in 1955. Unfortunately, Hayasaka passed away from Tuberculosis on October 15th, 1955 at the age of 41 before he could complete the score for the latter film. "Ikiru" opened theatrically in Japan on October 9th, 1952. Though the two biggest stars featured for the poster art was an ageing supporting actor and a former child star that only appeared in minor roles, the film was a massive hit with both audiences and critics. It was voted the top Japanese film of the year for the 1952 Kinema Jumpo list, which became the second film by Kurosawa to top the list with the first being "Drunken Angel" in 1948. It received three awards from the Mainichi Film Concours for Best Japanese Film, Best Screenplay, and Best Sound Design and two awards from the Visual Technical Awards for Cinematography and Sound. Internationally it was first screened at the Berlin International Film Festival in June 1954 where it won a special prize and was nominated for the Golden Bear. It was given a small American release in 1956 in California under the title "Doomed", but received a wider release in 1960 under its Japanese title. It continued to receive wide acclaim and accolades by touching audiences worldwide with its universal appeal and heartfelt message while also showcasing technical achievements with its cinematography, editing, set designs, and direction. It was officially remade for the first time in 2007, adapted by TV Asahi, in which they remade "High and Low" for broadcast on September 8th and "Ikiru" for broadcast on September 9th, with both being modernized adaptations. In 2022, the film was remade as "Living" seventy years after the original, but taking place in 1952 like the original film. Directed by Oliver Hermanus from a screenplay adapted by famed writer Kazuo Ishiguro, the film had many similarities but added a few unique touches to make it stand out on its own. Even with the high praise it received including two Oscar nominations, it did not diminish he impact of Kurosawa's original at all, with a stellar performance by Shimura in the lead. It's still one of the finest films ever made and will continue to inspire many more. Note this is a region B Blu-ray set

Video

The BFI presents the film in the 1.37:1 aspect ratio in 1080p AVC MPEG-4. The 35mm fine grain duplicating positive was scanned and restored in 4K resolution by Toho. The original nitrate negative was most likely discarded by Toho years ago, and the fine grain from their vaults is the best and closest element to the original negative. The 4K restoration has a lot of positives, as it has excellent grey scale, minimal wobble, and a cleaned up image. The black and white looks crisp, with details on faces, wardrobes, backgrounds in excellent focus, looking better than it has ever looked on any home video format. There are some instances of print damage and speckles that are very minimal, and there has been some smoothening of the image though there is noticeable film grain left intact. In comparison to the 2015 Blu-ray from The Criterion Collection which had their own 4K restoration shows additional wear and tear as well as some weaving of greys and a bit of film wobble at certain points. The Toho 4K restoration which was completed in 2016 for theatrical screenings has additional restoration applied and is the better of the two. In addition, there is much more breathing room for the film on the BFI Blu-ray, as the film takes up 44.44GB of the 50GB disc, compared to the Criterion Blu-ray using 28.89GB of its disc for the film as it shares all of its extras on the same disc. Again there are limitations with the visuals due to the condition of the print and only so much the restoration could do, though it is a fine and excellent restoration by Toho and an excellent transfer by the BFI, and should please fans and newcomers alike. The film's runtime is 142:48.

Audio

Japanese LPCM 1.0 (restored) Japanese LPCM 1.0 (unrestored) The original Japanese mono track is presented uncompressed. Note there are two Japanese LPCM 1.0 audio tracks, with the second track being only accessible by switching audio tracks during playback. Playing the film defaults to the first audio track which is the restored audio. Pressing the audio key during playback will play the unrestored audio track, which is track 2. Both tracks were restored from an optical master and restored through Sondor Resonances. For the restored audio track, there is still a lot to be desired. While instances of hiss, pops, crackle and other damage to the audio track have been removed for a cleaner presentation, there are issues with the dialogue and music being slightly on the muffled side. In addition to Watanabe Kanji's frail and quiet voice, it is sometimes hard to decipher if they are syllables or random sounds at points. The narration is also slightly low and doesn't have the power that most narrator cues would. Music comes in fine, though there are fidelity issues making cues sound a little flat. Most of these issues are due to the original source materials and the original recording process, but it is also a fact that audio restoration has some drawbacks as they can remove parts of the original dialogue's depth in the process. As for the unrestored track, it is possible to hear small hiss and pops in the background on careful examination, though note it is not completely "unrestored", as it is close to the restored audio track in terms of depth and fidelity. The hiss and pops are fairly quiet and the dialogue sounds slightly clearer, but it is not a major night and day difference as heard in other examples of unrestored vs restored audio tracks on BFI releases, such as "The Flavour of Green Tea Over Rice" and "A Hen in the Wind". There are optional English subtitles for the main feature in a white font. There are a few instances the subtitles do not translate the dialogue fully, missing some "Umm.." or "But..." moments at the start of sentences or repeated name calls such as when Kanji calls for "Mitsuo" over and over. Translation is excellent and the subtitles are easy to read.

Extras

This is a two disc set with the film and commentary on the first disc, a 50GB Blu-ray while the remaining extras are on a separate 25GB Blu-ray. DISC ONE Audio commentary by film critic Adrian Martin (2024) This new and exclusive commentary has Martin discussing about the film and Kurosawa, from information on his techniques with montages, close-ups, long takes, and the choreography of movement, the scriptwriting process, as well as discussions on the characters and their movement and stylistic choices, information on the British remake from 2022 and its differences, and more. He says at the beginning that he will not talk about the behind the scenes or the making of very much, and he does mention a few things but it is mostly observations that are screen specific. There could have been more information on the actors and the behind the scenes specifically, but it is still a solid listen throughout the lengthy runtime. in English Dolby Digital 2.0 without subtitles DISC TWO "Akira Kurosawa: It Is Wonderful to Create – Ikiru" 2003 documentary (41:37) When Toho issued their Kurosawa DVD boxsets in 2003, each film included newly created making-of documentaries entitled "It Is Wonderful to Create". Each had interviews from surviving cast and crew members, vintage clips, and much more for a fascinating look into the director's major filmography. Included are the writing process between the two screenwriters and Kurosawa, Shimura's casting in the lead for the first time in his career, Odagiri's memories of being directed in an unconventional form, the creation of the city hall set with the paperwork stacks, the intricate lighting effects and mirrored reflections, Kurosawa's initial negative reaction to a preview screening, and the film's reception. Like the rest of the series, it is incredibly well directed and the stories from interviewees (which most have passed away now) are absolutely priceless. There is one subtitle error, in which Kurosawa says that when Shimura shouted "Merry Christmas, everybody!" during the production of "Scandal", the English subtitles mistakenly state it was during the production of "The Idiot". Note that the translation error is also found on the Criterion DVD and Blu-ray releases. in 1080i60 AVC MPEG-4, in 1.33:1, in Japanese Dolby Digital 2.0 with optional English subtitles 2003 introduction by Alex Cox (14:46) This interview with filmmaker Alex Cox is first a biography of Kurosawa, from his early life and his older brother's influence, being hired by Toho and moving up to the ranks of director, notable points in his filmography, international recognition, his later works and his death. This is followed by information on "Ikiru" specifically, with Shimura's performance, the themes of the film, and its importance in Kurosawa's filmography. There is one point that he mentions that Shimura and Mifune Toshiro were about the same age but Shimura was actually 15 years older. Note this was originally available on the BFI's DVD release of the film. in 1080i60 AVC MPEG-4, in 1.33:1, in English Dolby Digital 2.0 without subtitles "It's Ours Whatever They Say" 1972 documentary (38:46) This documentary looks at the Loraine Estate in North London, where there are many families with children living in the area yet there is no playground for them to play, instead relying on dangerous parking areas as well as a derelict abandoned area next door. After a child died while playing in the area, the parents tried desperately to discuss having the location turned into a park for their children to the local council. This documentary directed by Jenny Barraclough looks at the parents and children involved in the march for change, as well as the city officials who give the locals the runaround by avoiding the issue with excuses. From the candid interviews to scenes of the police getting involved, it is a wonderful time capsule of perseverance making actual changes, and is a fantastic extra to be including with "Ikiru" for its similarity in the park building theme. It is presented here is black and white in a very grainy yet sharp image which has a number of damage marks and gate hairs visible due to the original documentary production on 16mm film, though the grey levels are quite good and the sound is also fairly clear, with some instances of echoes and muffled voices. The film is also available to watch for free on the BFI Player. It should be noted that it is strange that it is presented here in black and white on the Blu-ray, as the original broadcast on television in 1972 was in color. It isn't stated why a black and white version is included here and not the color version, though it might be due to a rights issue, as the documentary itself was independently produced and is under differing rights from the television series "Man Alive". The fully uncut episode of "Man Alive" with the documentary is embedded below, courtesy of the director's YouTube channel, and it includes the introduction and a panel discussion as it was originally aired. in 1080p AVC MPEG-4, in 1.33:1, in English LPCM 1.0 without subtitles "The People People" 1970 COI public service short (22:26) This short film by the Central Office of Information looks at the different jobs that are offered in civil service, looked through the eyes of a young photographer who is tasked to take photos of a number of new young workers. From mock interactions with people at city hall to explanations of what their tasks are, this short was made for students to encourage them to look into government work. The actors are not credited and while they are not exactly showcasing the best acting skills, the message does get across. The film is in color, while slightly faded still looks good with sharpness and detail. Sound is also adequate with narration and dialogue coming in clear while there is some hiss and pops that can be heard in the background. in 1080p AVC MPEG-4, in 1.33:1, in English LPCM 1.0 without subtitles Image Gallery (4:05) A series of behind the stills and promotional stills from the Toho vaults is presented here in a silent slideshow form. in 1080p AVC MPEG-4 Original Theatrical Trailer (3:30) The original Japanese trailer is presented here, restored in 4K and looks excellent with very few examples of damage to be found. The audio on the other hand is a little bit more muffled, though it is also restored. It is notable for featuring a few exclusive shots that are not present in the feature film. The trailer has also been embedded below. in 1080p AVC MPEG-4, in 1.37:1, in Japanese LPCM 1.0 with optional English subtitles Booklet A 24 page booklet is included with the first pressing. First is an essay simply titled "Ikiru" by writer/film historian Tony Rayns which looks at the film's background, its themes, and its impact. Next is a review of the film from 1959 by John Gillett originally published in Monthly Film Bulletin No 307. This is followed by "Shimura Takashi: To Live a Wonderful Life" which is written by James-Masaki Ryan. Yes, me of all people. The essay focuses on the life and work of Shimura as well as some personal thoughts about cancer affecting my own family and relatives. Much of the content on Shimura's life is reprinted above in my review of the film, though there are some differences in the booklet. It should be noted that I made a spelling error by naming Shimura's wife as "Masaki" as her name is "Masako". (Spellcheck seems to have thought it was my own name.) I'm absolutely honored that I could be part of this release as how personally affecting the film has been for me and I owe a great deal of thanks to the BFI. There are also special features information, full film credits, notes on the presentation, acknowledgements, and stills. The film has been released in numerous editions on DVD and Blu-ray in the past. Toho Japan released it first on Blu-ay in 2009, though they made the strange decision to leave off the "It Is Wonderful to Create" series of documentaries and other extras for their Blu-ray upgrades. Criterion in the US upgraded their 2-disc DVD set to Blu-ray in 2015. This included audio commentary by Stephen Prince, the lengthy 2000 documentary "A Message from Akira Kurosawa: For Beautiful Movies", the "Akira Kurosawa: It Is Wonderful to Create - Ikiru" 2003 documentary and the original trailer. The commentary has a lot of great information from the well spoken Price who passed away a few years ago, though his pronunciation of Japanese names and words were utterly cringy as he made frequent mistakes. The 2000 documentary has a lot of vintage clips with Kurosawa and others who have worked with him, and also has a lot of behind the scenes footage of his 1991 feature "Rhapsody in August". The trailer here it should be noted is a standard definition upscale so there is a lot more damage and is blurrier than the transfer on the BFI release. There are also Blu-ray releases from France and Spain with their own differing exclusive extras, and in 2023 Toho Japan released both a remastered Blu-ray and a 4K UltraHD release of the film. Sadly, both only include the trailer and a stills gallery, and lack the "It Is Wonderful to Create" 2003 documentary. Other notable clips: "Song of the Gondola" by singer/actress Chieko Baisho Kurosawa on "The Dick Cavett Show" in 1981 Kurosawa receiving an honorary Oscar in 1990 Promo for the 25-film 25-disc "AK100" DVD boxset from The Criterion Collection "Kurosawa: A Complete Film Season" BFI trailer, featuring "Ikiru", which ran from January - February 2023 Patton Oswald on "Ikiru" The trailer for the 2022 remake "Living"

Overall

"Ikiru" is without a doubt a major milestone in Kurosawa's career and a masterwork in heartbreak and inspiration. It is filled with emotional depth as well as humor and has transcended generations with its story while also being a major technical achievement. The BFI's 2-disc Blu-ray release is a fantastic one, with a great transfer of the 4K restoration by Toho and a great number of vintage and new extras. Highly recommended. Amazon UK link BFI Shop link

|

|||||

|