|

|

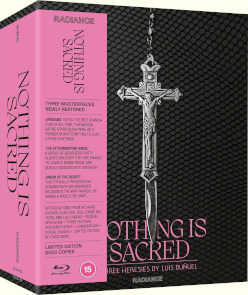

Nothing is Sacred: Three Heresies by Luis Buñuel (Viridiana/The Exterminating Angel/Simon of the Desert)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Radiance Films Review written by and copyright: Eric Cotenas (14th January 2025). |

|

The Film

"From 1946 to 1965, Luis Buñuel directed 21 films in Mexico, the country that became his naturalised home. Towards the end of this period, the great master of surrealism would meet two of his most important collaborators - the husband-and-wife duo of producer Gustavo Alatriste and actress Silvia Pinal - and together they would create three of his most provocative and enduring works: Viridiana (1961), The Exterminating Angel (1962) and Simon of the Desert (1965). Presented here in new restorations, all three films are frequently hailed as some of the greatest of all time. All of what makes Buñuel one of the greatest of directors can be found within them: the startling imagery, the uncompromising surrealism, the wicked humour, the unapologetic eroticism, and the overwhelming disdain for contemporary boundaries of good taste." Palme d'Or: Luis Buñuel (winner) - Cannes Film Festival, 1961 Grand Prix de l'UCC: Luis Buñuel (winner) - Grand Prix de l'UCC, 1962 Top Ten Film Award (Best Film): Luis Buñuel (Fourth Place) - Cahiers du Cinéma Viridiana is a novice (Las mariposas disecadas' Silvia Pinal) eager to leave the outer world behind when her uncle Don Jaime (The French Connection's Fernando Rey) invites her to visit him. Viridiana intends to refuse the invitation but the Mother Superior (Rosita Yarza) orders her to make the journey to pay her respects to her benefactor who is not long for this world. In spite of Don Jaime's ingratiating manner, Viridiana is unable to pretend that while she has the utmost respect for him, she feels little affection, and her pious behavior upsets the household with housekeeper Ramona (Jean de Florette's Margarita Lozano) disturbed to discover that the young woman sleeps on the floor with a cross and a crown of thorns. The only person for which Viridiana expresses any sort of warmth is Ramona's daughter Rita (The Killer is Not Alone's Teresita Rabal). Don Jaime is frustrated by Viridiana's acquiescent yet cold manner and presses Ramona to help him prolong his niece's stay. Despite her misgivings, Viridiana consents to her uncle's strange request on the eve of her departure to wear his wife's bridal gown in which she died of a heart attack in his arms on the their wedding night. Viridina is shocked when Ramona reveals that Don Jaime wants to marry her, offering her security and comfort, but Ramona has already drugged her tea at her master's request. When Viridiana wakes the next morning, Ramona claims that she fell ill but Don Jaime confesses to forcing himself upon her in her sleep so that she cannot return to the convent a virgin. Seeing the disgust and hate in Viridiana's face, he tries to convince her of the truth that he was tempted but only possessed heri in his mind but she is even more determined to leave; whereupon, Don Jaime hangs himself, leaving behind a will dividing his fortune and his house between his illegitimate son Jorge (L'eclisse's Francisco Rabal) - born to another woman before his wife's death – and Viridiana. Feeling guilt for her uncle's mortal sin, Viridiana tells the Mother Superior that she will not return to the convent but instead intends to try to live humbly and help others but on her own. She invites the village's vagrants to live on the estates in dormitories divided by sex, much to annoyance of Jorge and his girlfriend Lucia (The Wild, Wild Planet's Victoria Zinny). Lucia sees Viridiana as crazy but harmless while Jorge thinks her "rotten with piety" and estranged father and son may have more in common than they would admit. Director Luis Buñuel's first film shot in his native Spain after apprenticing under Jean Epstein () in France, making his surrealist early directorial efforts Un chien andalou and L'âge d'or, and working for twenty years in Mexico, Viridiana was a perverse choice for the director to make for his homeland under authoritarian rule, more so because it was sent to Cannes by the Spanish censor and won the Palme d'Or even as it was being labeled blasphemous by the Catholic Church and banned in his native Spain (the negative only survived the order for it be burned because it was physically in another country). On the surface, the film attacks both the traditional landowners and the petit bourgeousie through father and illegitimate son, religion by subtly sexualizing and fetishizing Viridiana's devotion, and depicting the poor not as pitiable victims but as opportunistic as their "betters" who turn an impromptu tableau vivant of "The Last Supper" into a drunken orgy under the film's second use of the Hallelujah chorus from Handel's "Messiah". More interesting than the overt perversions – including Jaime's attraction to Viridiana which borders on necrophilia as he seems to realize that he has turned her into the image of his bride in life and death – are the power dynamics at play in the relationship between Jaime and faithful, indebted housekeeper Ramona along with Jorge's own feelings of entitlement to her, the way in which Jorge effects Viridiana's rescue from violation through the offer of cash for murder, and the manner in which the vagrant's desire to see what the house looks like when the masters are away devolves into a feast and orgy in which they express contempt for both scornful Jorge and their benefactress, all in contrast to majordomo Mancho's (Francisco René) unsuccessful attempts to distance himself from the vagrants or demand that Rita show some respect to her mother's late employer. While everything that Viridiana does is done with good intentions, it is easy to see just why others might question the nature of her piety. Despite her compassion for the poor, she is emotionally cold and seems oblivious to the effect of speaking honestly. Even before she announces her decision not to return to the convent but to "work humbly" on her own, the Mother Superior seems aware of Viridiana's pride. It is also not difficult to understand why the vagrants may resent her, with the one who decides not to follow her bristling at her assertion that she is qualified to teach them "humility and discipline." So narrow is her worldview that she is as ignorant of their real feelings as she is unable to see any trace of malice in Rita who we see dumping a glass of freshly-squeezed milk on a cow's head, skipping rope under the tree where Don Jaime hanged himself with the same rope, and burning Viridiana's crown of thorns in a leaf pile at the moment Viridiana seems to have lost her faith. The film is loosely based on the novel "Halma" by Benito Pérez Galdós, whose novel "Tristana" would be the source for Buñuel's 1970 film which shares similar themes (or variations upon them). The setup also seems as though it was an influence on Paweł Pawlikowski's 2013 film Ida whose protagonist is urged by her Mother Superior to visit her only surviving aunt whose carefree but empty lifestyle threatens to rub off on her while they attempt to discover the fate of her parents and the aunt's son during the German occupation of Poland two decades before. Produced by Pinal's husband Gustavo Alatriste, Catalan experimental filmmaker Pere Portabella (Cuadecuc, vampir), and Ricardo Muñoz Suay – who would subsequently become better known for his more mainstream exploitation productions like Horror Rises from the Tomb and Night of the Sorcerers – the cast is also peopled with a wealth of jobbing actors who (like the male leads themselves in later years) sometime had bigger roles in mainstream films as "character actors" but rarely the type of nuance seen here including José Calvo as the blind, seemingly wise Don Amalio who might be better-known as Clint Eastwood's saloon owner confidante in A Fistful of Dollars, José Manuel Martín as Cojo the religious painter who would later get his throat torn out in the opening of Count Dracula's Great Love, and Lola Gaos as a somewhat earthier version of the matronly enablers she would play in films like Blood Ceremony (as Countess Bathory's black magic-practicing handmaid) and Panic Beats not to mention graduating to housekeeper in Tristana. The film's assistant director was Buñuel's son Juan Luis Buñuel whose own directorial career tended towards a lighter, more accessible surrealism with films like The Woman in Red Boots reuniting Tristana stars Rey and Catherine Deneuve. Palme d'Or: Luis Buñuel (nominee) and FIPRESCI Prize (Competition): Luis Buñuel (winner) - Cannes Film Festival, 1962 Silver Goddess (Best Supporting Actress): Jacqueline Andere (winner) and Best Actress in a Minor Role: Rosa Elena Durgel (winner) - Mexican Cinema Journalists, 1967 Top 10 Film Award (Best Film): Luis Buñuel (nominee) - Cahiers du Cinéma, 1963 In The Exterminating Angel, Lucia (The Children That I Dreamed's Lucy Gallardo) and Edmundo Nobile (OK Cleopatra's Enrique Rambal) invite sixteen of their friends to a dinner party after an evening at the opera in honor of singer Silvia (Cry of the Bewitched's Rosa Elena Durgel) and conductor Alberto (Even the Wind Is Afraid's Enrique García Álvarez). Before the guests even arrive, majordomo Julio (Alucarda's Claudio Brook) is aghast at the inexplicable departures of the footman, the servers, the cook, and the kitchen staff but carries on with only one server who Lucia dismisses herself when he too offers nothing but the feeblest explanation for why he needs to leave. At the dinner table things proceed as expected with only the hostess making a faux pas with a practical joke that amuses all but one guest, causing her to abort a subsequent gag involving a bear cub and three sheep. During the after dinner amusements – including a piano recital by Blanca (The Curse of Nostradamus' Patricia de Morelos) – Lucia tries to steal away with lover Alvaro (Suicide Mission's César del Campo) – but no one seems to be in a hurry to leave as the night winds down, with sofa naps turning into an impromptu slumber party as more guests claim a portion of the drawing room floor. Even Julio once he crosses the threshold into the drawing room reluctantly disobeys his employers' orders, experiencing physical pain when he tries to leave along with guest Leonora (The Bloody Vampire's Bertha Moss) who, like Alberto, is consigned to bed rest by doctor Carlos Conde (Espiritismo's Augusto Benedico). Lucia and Edmundo play the good hosts despite their veiled annoyance; however, the next morning the guests finally realize as they try to leave the room for breakfast and freshening up that they physically cannot cross the threshold. As the hours turn into days, panic and paranoia set in as the need for food and water causes all vestiges of civility to slip away. While the central situation of The Exterminating Angel is never explained even in a "No Exit" sense, Buñuel teases his audience with other seemingly surrealistic imagery before revealing logical explanations of them to the viewer and the characters, from the appearance of three sheep and a bear that turns out to be part of a practical joke planned by Leticia, Ana (Mysteries of Black Magic's Nadia Haro Oliva) opening up her purse to retrieve a handkerchief and revealing in it the presence of chicken feet, or Blanca being attacked by an ambulatory severed hand turning out to be a fever-induced hallucination. Viewers anticipate the gradual slippage of the mask of civility, but the formal dinner allows the viewer to observe just how much of a mask it is as they overhear gossip about Leticia (Sylvia Pinal) – nicknamed "Valkyrie" because she fiercely guards her virginity against the interests of many suitors which her social circle has deemed a "perversion" – throwaway classist remarks ("I think the lower classes are less sensitive to pain" says one guest comparing her recollection of witnessing a mass calamity to those who actually suffered it), and Carlos confiding Leonora's cancer to everyone but her, sly insults by bully Raul (The Invasion of the Vampires' Tito Junco), and laugh raucously at a servant who has tripped and fallen with a plate of food which is not an accident but one of Leticia's jokes which amuses all but one. Certain interactions are repeated without explanation and sometimes without notice. The cooks' attempt to leave is twice interrupted by the arrival of the same guests. Edmundo makes the same toast twice, being disregarded by all including the main recipient along the second time with his pride visibly wounded. Sergio (The Holy Inquisition's Antonio Bravo), Leandro (The World of the Vampires' José Baviera), and Cristian (Luis Beristáin) are introduced amicably, run into one another again like old friends, and a third time with overt animosity. All of this occurs even before the seeming mass decision to spend the night sleeping in the drawing room which they all acknowledge as "violating the most basic precepts of good etiquette." Some of the guests realize that night that they cannot leave but nevertheless observe and anticipate the reactions of others who try to find excuses as to why they cannot cross the threshold, already delineating themselves within their class. The mask of civility truly slips as the guests can no longer maintain their outer appearances in terms of cleanliness but also physical separation, with the hosts erecting a curtain between their space and the rest and the young lovers (100 Cries of Terror's Ofelia Montesco and Two Mules for Sister Sara's Xavier Massé) camping in a water closet that becomes their tomb. The attacks turn personal with the guests blaming Edmundo for tricking them into a trap and debating whether killing him will free them – and Leticia responding to a Raul's threat of what he would do if she were not a woman by slapping him thrice – attacks on personal appearances and body odors even as one remarking admits that they all smell that way, and the exposure of perverse relationships like the doting of spinster sister Juana Avila (The Brainiac's Ofelia Guilmáin) on her much younger brother Francisco (Santo vs. the Vampire Women's Xavier Loyá) bordering on incest and enabling his bratty behavior even to the point of her physically attacking the man who gives Francisco a slap for his own physical assault. The confinement seems to accelerate illnesses some of the guests have managed to physically hide including Leonora's cancer and Cristian's ulcer (Raul finds Cristian's medication and amuses himself by tossing it into the dining room beyond their reach), and Alberto's overall exhaustion from keeping up with Silvia on the stage and after hours. The "descent" into bestial behavior of crowding a burst pipe for water, Ana initiation Silvia and Alicia into kabbalistic rites, and hunting and killing the sheep for food seems almost "communal" in comparison. Cutaways to the outside world are a combination of quarantine and media circus with multiple nutcases turning up offering to solve the issue and being turned away. That the solution to undoing the trap as a repeat performance of their actions and remarks that night suggests a need to be aware of behavior so that it does not become meaningless, routine (or ritualistic), and easily forgotten. That the survivors become trapped again in the cathedral attending a mass they promised they would attend – only bargaining with God with the conditional "if" of getting out of their current situation – suggests that if they are specifically being "punished" it is because they are fulfilling an obligation (and possibly also being seen to do so by the lower classes to view them and their class as being blessed). Special Jury Prize: Luis Buñuel (winner), FIPRESCI Prize: Luis Buñuel (winner), and Golden Lion: Luis Buñuel (winner) - Venice Film Festival, 1965 The Exterminating Angel's Claudio Brook is Simon of the Desert, an ascetic who has stood on a pillar exposed to the desert elements for six years, six months, and six days, attracting benefactors, followers, and those seeking miracles. His graduation to an even taller pillar moves him closer to Heaven but seemingly farther from God as he finds it harder to ignore the mockery of his own brothers – and conversely the admiration of beardless Brother Matias (Enrique Álvarez Félix) – the quiet suffering of his mother (Poison for the Fairies' Hortensia Santoveña) who has camped nearby – which seems a passive aggressive move as she does not appear to be near death as she claimed when she asked the church to be near to her son – the failings of the flesh in his hunger, sun-parched skin, and aching feet, as well as the temptations of earthly pleasures offered by the devil "herself" (Viridiana's Silvia Pinal) who even turns up in drag as God to encourage Simon to enjoy himself. Despite its overtly religious themes, Buñuel's Simon of the Desert is not calculated to outrage the Catholic Church. Like Viridiana, Simon is so focused on his faith that he is less-worldly, and some might detect arrogance in the ways he faults even his fellow brothers for perceived lapses and resentment on their part. Unlike Viridiana, Simon has tried to remove himself from any sense of power or authority over anyone else, not promising help only to pray for those in need (although perhaps "his" congregants feel no less beholden to him than the vagrants to Viridiana). While his brothers, a shepherd, and others only indirectly challenge him – even Brother Trifón (The Aztec Mummy's Luis Aceves Castañeda) challenges him on the basis of "finding" rich foods in Simon's bag rather than his usual diet of lettuce leaves – Simon's main conflicts are between his faith, the wanderings of his mind, and the needs of his body which are preyed upon by the devil; and in this sense, Simon of the Desert is an overtly supernatural film. While Simon is the only one who sees the devil – apart from one of the brothers whose gaze she catches before she introduces herself to Simon who only sees a one-eyed hag where another brother (Book of Stone's Eduardo MacGregor) sees a beauty, or so we are fooled as Simon lies to expose the brother's distraction – even with his mother camped nearby, and Brother Trifón's "possession" could be an act to get himself out of trouble after being exposed trying to damage Simon's credibility, and one wonders whether the order of Brother Zenon (The Criminal Life of Archibaldo de la Cruz's Enrique García Álvarez) to move him elsewhere so that he may exorcise him "in my own way" is an attempt to remove the influence from Simon's presence or if he might have been in on the attempt to discredit the would-be martyr – even those who dismiss Simon's miracles as "spiritual shenanigans" witness the restoration of a punished thief's severed hands; indeed, going by the way the church seems less impressed by said miracle than their benefactors, and the thief and his family react to the restoration of his hands, it appears that such miraculous occurrences and belief in them are business-as-usual. The devil's appearances in anachronistic costuming like a schoolgirl's uniform or emerging from a modern coffin – in a sequence that momentarily channels Nikolai Gogol's novel "The Viy" – lend the film an almost Fellini-an camp rather than Buñuel absurdity (especially as Pinal's schoolgirl iteration of the devil brings to mind the more comic performances of Giulietta Masina). Rather than ridiculing Simon's fanatic asceticism, Buñuel instead take subtle shots at the self-interest of the church as represented by Simon's brothers, the prestige of the benefactors, and the entertainment-seeking audience of congregants – all of whom seem less ingenuous in their performative worship than Simon's own performance of asceticism. Unlike Viridiana, Simon realizes the potential for corruption when he absently thinks to himself that it is "fun" and "harmless" to bless people, although who is to know if his self-imposed physical punishment is anything more than a gesture. We do not know just when Simon's will falters or if it even has to for the devil to sweep him away to Hell which is depicted as the modern world of jet planes, nightclubs, jazz music, and frenetic dancing. This ending seems less of a conservative statement than a mocking of both the type of audience members who go see a Buñuel film to be outraged and perhaps overly-analytical critics. One of Buñuel's unrealized projects was an adaptation of Matthew Lewis' "The Monk" – his script would eventually be filmed by young colleague Adonis Kyrou, and one cannot help but wonder if the Simon of the Desert was the genesis of this project or a sketchpad for working out some of its ideas (although there is no suggestion that Mathias is another incarnation of the devil, the fact that actor Félix would later play Dorian Gray makes one wonder whether there is not a slight hint of jealousy and envy of his looks on Simon's parts as he chastises him).

Video

Viridiana was released theatrically in the U.K. by Miracle Films in 1962 with an X-certificate and re-released in 1995 with a 15-certificate by Electric Pictures followed by a VHS edition. The Video Mercury digital master released in 2006 stateside by Criterion and in the U.K. by pre-Arrow Video Arrow Films looked alternately too dark and washed out in terms of monochrome contrasts, but it was easy to assume due to the film's reputation whatever materials Spain had might not be that close to the negatives given that the film was banned in 1962 and not released there until after Franco's death. Radiance Films' 1080p24 MPEG-4 AVC 1.66:1 widescreen Blu-ray comes from a new 4K restoration that looks more stable across scenes, lending a slick elegance to the Gothic decay of the interiors of Don Jaime's villa and a rustic grittiness to the exteriors and the environs of the farm buildings. As with the earlier transfer, there is a short sequence at roughly ten minutes involving the first mention of Don Jaime's illegitimate son which has been noticeably inserted from inferior materials, becoming softer, darker, and jittery compared to footage in the same shot before and the following scene (this might also be inherent in the original materials given stories of the film's tumultuous post-production and piecemeal transport to Cannes). This is the best it has looked, and this may be a case where an actual 4K HDR edition might not be that significant an upgrade and might even call attention to other instances of wear and patchwork. The Exterminating Angel was released in the U.K. in 1966 with an X-certificate and re-released in 1995 by Electric Pictures who also put the film out on VHS. While we have not seen that version, Arrow's 2006 DVD was a must-to-avoid since it deleted the repeated arrival of the guests as an apparent mistake – well, either Arrow or the rights owner – while Criterion's 2009 Region 1 DVD was windowboxed but sported a sharper image, better contrasts, and the film was completely intact. Criterion's 2016 Blu-ray came from the same master without the windowboxing, and apparently that same master has been utilized for Radiance Films' 1080p24 MPEG-4 AVC 1.37:1 pillarboxed fullscreen Blu-ray with identical framing and contrasts. While it is regrettable that we did not get a new master like the other two films in the set, it still gets the job done. Not released theatrically in the U.K. until 1968 and re-released theatrically and on home video in 1995 by Electric Pictures, Simon of the Desert did not have a U.K. DVD release but the curious could import Criterion's 2009 DVD sourced from a high definition master. Fifteen years later, U.K. company Radiance Films debuts a 4K restoration for their 1080p24 MPEG-4 AVC 1.37:1 pillarboxed fullscreen Blu-ray and it is a stunner. The film was shot almost entirely outdoors in bright sun – a few washed out shots appear to be deliberate overexposure to give a sense of the heat – but virtually every single shot from close-ups to wide convey a range of textures from the contrasts of Simon's parched skin and the glamorous looks of Pinal's incarnations to the weathered textures of the stone pillars (which also reveal the artistry that went into making these pieces commissioned within the film by wealthy benefactors). A few opticals look coarser along with some stock footage, while the finale sports deep blacks and good detail when not focused on the frenetic dancers (who might have been slightly undercranked).

Audio

Viridiana's sole audio option is an LPCM 2.0 Spanish track which sports clear, post-dubbed dialogue, sparse effects, and a few classical music passages that possibly sound coarser because they are meant to sound sourced from Don Jaime's record collection as played through a phonograph. The aforementioned passage inserted from a different source does sound slightly muffled. Optional English subtitles have been newly-created and may be a little more frank than what played theatrically in the sixties. Criterion apparently ran into some issues when they tried to clean up The Exterminating Angel's "high fidelity" audio supplied by the master introducing digital artifacts to a noisy track. While that has not been done here, post-dubbed dialogue is always intelligible but optical track hiss is loud during the supposed silences here. Optional English subtitles are free of errors. Simon of the Desert's LPCM 2.0 mono track is the cleanest-sounding of all three, with real preternatural silences in the desert exteriors as Simon's mind turns inward and the devil makes her appearances. Post-dubbed dialogue is always clear, effects are sparse, and music only really makes its presence known in the final scene.

Extras

Extras for Viridiana start with a most-informative audio commentary by film historian Michael Brooke who discusses the film's perverse and fetishistic elements, liking the film's elements to Gothic traditions and likening the film's depiction of pseudo-necrophilia to Epstein's The Fall of the House of Usher on which Buñuel worked as an assistant. He discusses the characters and the power dynamics between them, contrasting how Don Jaime and Jorge get what they want, as well as discussing the film's controversies. Most interesting is his observation that the film was not unanimously condemned by the Catholic Church and even had defenders in critics writing for Catholic publications, including one who felt that the film was not an attack on Catholicism as a whole but on the romanticized view of "prig" Viridiana in love with the externals of religion. He also reveals that before Viridiana, Buñuel had attempted to mount an adaptation of Galdós "Tristanta" with Pinal but found no interest. "The Life and Times of Don Luis Buñuel" (101:17) is a 1983 BBC documentary by Anthony Wall (who provides an optional introduction (9:50) – and narrated by Paul Scofield (A Man for All Seasons) and released shortly after the director's death. It intercuts readings from the director's autobiography and home movie footage with interviews from associates Rey, actresses Jeanne Moreau (Diary of a Chambermaid) and Deneuve, novelist Carlos Fuentes (Time to Die), and screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière (The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeosie) to get to know the enimgatic figure in all of his contradictions. The disc also features an appreciation by filmmaker Lulu Wang (10:56) who recalls her discovery of the wider body of Buñuel's filmography after film school, her admiration for Viridiana and the notion of "shame" in the director's works. There is also a 1964 interview with director Luis Buñuel for French TV's "Cinéastes de notre temps" (47:46), the first episode of the series which ran from 1964 to 1971. A casual outdoor interview with the director in good humor here – despite his increasing withdrawal from socializing due to his deafness – in which a braying donkey occasionally interjects is intercut with comments from more Buñuel associates include Kyrou, the great Max Ernst, the director's wife Conchita, and critic George Sadoul who relates some humorous anecdotes. At the time of the documentary, L'âge d'or was still banned so it could only be illustrated here through still images (presumably due to the lack of an accessible print rather than a censor-appeasing move). The disc closes with a gallery. The Exterminating Angel features an appreciation by filmmaker Alex Cox (9:39) who focuses less on the film than on how Buñuel ended up in Mexico by way of France, New York, and Los Angeles, along with his lesser-known genre films preceding Viridiana, and Cox's own visit to Mexico and Buñuel's home along with his souvenir bullet (Buñuel was anti-violence but a gun collector). "A Mexican Buñuel" (55:43) is a 1995 documentary by Emilio Maillé greatly expands upon Cox's remarks about how Buñuel wound up in Mexico after working in Hollywood studios for the Spanish government, getting fired from his New York job at the Museum of Modern Art translating Spanish Civil War documentaries when Salvador Dali denounced him as a communist, and his invitation to Mexico from editor Denise Tual, and a more in-depth look at his early pre-Los olvidados, including his musicals and his Hollywood-produced, English-languge, Mexico-shot The Young One as well as introducing us to Pinal – who appears in interviews – and Alatriste along with frequent collaborator cinematographer Gabriel Figeroa and even the manager of the hotel where the director rented a regular room to write going back to the time when the former was just a porter. There is also an appreciation by filmmaker Guillermo del Toro (18:55), and just as he provided a primer on releases of his own works to the Gothic as a literary and cinematic genre, here he provides an engaging discussion of surrealism referencing Buñuel's works, noting that unlike more montage in more conventional narratives, surrealist ones combined images not to merge them into one meaning but to open up a multiplicity of interpretation. He also discusses Buñuel's early Mexican works, drawing upon the Mexican Churro and the Spanish "flat Churro" the Bunuelo as a means of describing the more lightweight efforts in contrast to the later films and their controversial receptions. As a practitioner of the cinematic Gothic, it is surprising that his appreciation was not included on the Viridiana disc but in discussing that film at length here, he does hit upon some recurring motifs and themes that are present but less pronounced in The Exterminating Angel. "Dinner and Other Rituals" (16:52) is a visual essay by critic and writer Alexandra Heller-Nicholas who discusses the role of the dinner as performative ritual and the potential for observing human nature – both in establishing social roles and violating them – contrasting the dinners in Viridiana and The Exterminating Angel and the multiple attempts at one in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeosie and the toilet dining of The Phantom of Liberty as well as discussing eventful dinner scenes in films by other directors like Festen, Caché, and Rope. The disc closes with a behind the scenes gallery. Extras for Simon of the Desert start off with an appreciation by filmmaker Richard Ayoade (14:55) who, like Wang on Viridiana is less analytical than enthusiastic in discussing the impact of the director on him as a film viewer and later film maker. "The Other Trinity: Alatriste, Buñuel and Pinal" (32:35) is a visual essay by film historian Abraham Castillo Flores who discusses the collaboration between the three, noting that Pinal had wanted to work with Buñuel before, trying to get the adaptation of "Tristana" off the ground during the production of The Criminal Life of Archibaldo de la Cruz (whose co-star Ariadne Welter was Alatriste's first wife), and the funding for Viridiana came about as the result of businessman Alatriste wanting to grant second wife Pinal's wishes. In spite of the issues the film met with the Republican Army during production the Catholic Church and Franco upon its release, the experience was rewarding, with Alatriste encouraged to pursue his interest in film by Buñuel and Pinal insisting on having a role in The Exterminating Angel even though it was an ensemble piece (resulting in Buñuel adding the character of Valkyrie). Interestingly, Flores reveals that Buñuel attributed Simon of the Desert's short running time to funding issues and the cutting of several major unfilmed or unfinished sequences while Pinal insisted that the film was intended to be part of an anthology film with offers for other entries to Fellini and Jules Dassin falling through because they insisted on starring their wives (the portmanteau film with several stories by different directors built around one starlet was not without precedence including more than one for Silvana Mangano greenlighted by her husband Dino De Laurentiis). Flores also covers the deterioration of the collaboration, with the separation and divorce of Alatriste and Pinal over his infidelities and her reluctance to be directed by him – Alatriste would later marry actress Sonia Infante who would not only be directed by him but would herself become a producer of some of her own vehicles including an adaptation of Lorca's "Bernarda Alba" which was the project in which Pinal initially attempted to get Buñuel involved – and Buñuel's French films. One of the last extra features on the final disc in the set, "Buñuel: A Surrealist Filmmaker" (87:08), a documentary by Javier Espada that played at Cannes in 2021 would perhaps have been best watched first. Whereas "The Life and Times of Don Luis Buñuel" on the first disc develops its themes and structure from the remarks of Buñuel's colleagues, "Buñuel: A Surrealist Filmmaker" feels like an illustrated college essay, steadfastly chronological in discussing the director's upbringing, his early education, and the phases of his career in a continuous narration over hundred of stills that all robotically transition from black and white to colorized and various clips. A lot of what is discussed will be old hat to those who have watched the other extras in the set first but some interesting topics of discussion occur early on including the influence of the director's parents and other relatives, including elements of the proto-surreal and grotesque in the stereoscopic photographs taken by his father. The disc also includes a gallery for the film.

Packaging

The limited edition of six-thousand copies is presented in a rigid box with full-height Scanavo cases in a slipcase with a removable OBI strip leaving packaging free of certificates and markings and an eighty-page book featuring new writing by Glenn Kenny, Justine Smith, Lindsay Hallam and David Hering, as well as archive material (sadly not supplied for review).

Overall

The three so-called "heresies" made by director Luis Buñuel during his jobbing Mexican period – including one regarded by critics as the greatest Spanish film ever made – are less overtly absurd than his better-known later French films but still possess "discreet charms" to reward the viewer.

|

|||||

|