|

|

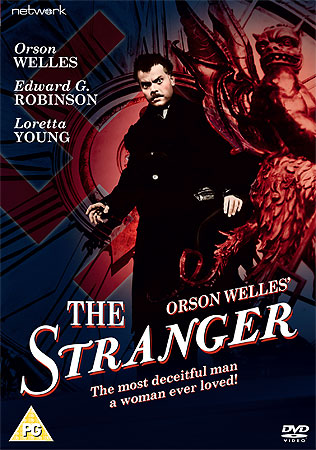

Stranger (The)

R0 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (9th January 2009). |

|

The Film

Produced in 1946, The Stranger was Orson Welles’ third feature as director, produced between The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) and The Lady From Shanghai (1947). The Stranger is often referred to as Welles’ most conventional film or his weakest picture, although by Welles’ standards a ‘lesser’ picture is still never less than eminently watchable. The Stranger is a classic suspense melodrama of the kind that has, since the 1960s, come to be labelled an example of film noir. Like Welles’ other films from this period, The Stranger makes use of low-key lighting and some obtuse camera angles (there’s particular use here of Welles’ favoured high-angle close-ups), all of which have come to be seen as part of the iconography of films noirs.  In The Stranger, Welles plays Franz Kindler, a top-ranking Nazi official (modelled on Martin Boorman) who has managed to evade the Allies’ War Crimes Commission and has sought refuge in small town America, making a new identity for himself as a teacher in Harper, Connecticut. Living under an assumed identity as Professor Charles Rankin, Kindler appears to be a model citizen, and as the film opens he is preparing to marry a local girl, Mary Longstreet (Loretta Young). However, a member of the War Crimes Commission, Mr Wilson (Edward G. Robinson), has developed a plan that will enable him to ensnare Kindler: Wilson releases a former associate of Kindler’s, Konrad Meinike (Konstantin Shayne), from custody and follows Meinike to Harper. However, in Harper Meinike becomes aware of Wilson’s presence and assaults Wilson, leaving him for dead; Meinike then visits Kindler, making him aware of Wilson’s intention to capture him. Realising that Wilson does not know Kindler’s new identity and that Meinike is the only clue to his past, Kindler throttles Meinike and hides his body in the nearby woods. With the knowledge that Kindler is hiding out in Harper and in the absence of Meinike, Wilson is faced with the task of discovering Kindler’s new identity and, once this has been completed, convincing the townsfolk of Kindler’s deceit. However, no images of Kindler exist, and the key clue to his identity lies in his love of clocks; but can Wilson convince Mary Longstreet of her new husband’s real identity without placing her in peril? The narrative of The Stranger is reminiscent of Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943), in which Welles’ frequent collaborator Joseph Cotten plays a sociopath, Charles Oakley. In Hitchcock’s picture, Oakley is under investigation on suspicion of being ‘The Merry Widow Murderer’ but manages to conceal his identity by hiding amongst the Newton family (as ‘Uncle Charlie’) in the North Californian town of Santa Rosa. Hitchcock’s film brought the terror of tyranny home for many wartime audiences, eroding the distinction between ‘us’ and ‘them’ and showing that evil was not something that simply existed ‘out there’—on the European Front, or in the ideology of Nazism. Welles’ The Stranger performs a similar trick by showing how easy it is for a former Nazi to evade detection through assuming a new identity in small town America. When Mary asserts to Wilson that she has ‘never even seen a Nazi’, Wilson undercuts her arrogance by telling her that ‘you might without even realising it: they look like other people and act like other people’. In the introduction to the book Hitchcock’s America (1999), Jonathan Freedman and Richard Millington refer to Shadow of a Doubt as a picture that exposes the idea of small town ‘normativeness as being […] wholly simulacral, both a pose for and the creation of the media who ostensibly record it’ (3). In Hitchcock’s film, Freedman and Millington argue, the ‘perfect American wife’ (Mrs Newton) is shown, through her ignorance of the real identity of ‘Uncle Charlie’, ‘to be a perfectly clueless ditz whose obtuseness about her male relations mimics the willed ignorance’ of small town life—or rather, a certain idealised representation of small town life that has been constructed by ‘middlebrow magazine[s] and the Hollywood film[s]’ (ibid.). Freedman and Millington go on to suggest that in Hollywood cinema, small town life has been placed in opposition to city life: where the city is the ‘home of crime […] and lonely, familyless women to be preyed on by the likes of the Merry Widow killer’, small town life has been represented as the ‘home of family values […] and quiet evenings at home spent reading gruesome accounts of murder’ (ibid.: 4). Robin Wood once famously stated that ‘[w]hat is in jeopardy’ in Shadow of a Doubt is ‘above all The Family [….] The small town […] and the united happy family are regarded as the real sound heart of American civilization; the ideological project is to acknowledge the existence of sickness and evil but preserve the family from their contamination’ through establishing clear boundaries between small town family life and deviant behaviour (in Shadow of a Doubt, deviant behaviour is framed as misogyny and homicidal violence; in The Stranger, deviance is defined through association with the ideology of Nazism) (Wood, quoted in Michie, 1999: 30). Like Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt, Welles’ The Stranger also deconstructs this representation of small town life: instead of the townsfolk spending ‘quiet evenings at home spent reading gruesome accounts of murder’ whilst unaware of the presence of The Merry Widow Killer in their midst, Welles paints a picture of small town life as a place in which the upper middle class spend their evenings discussing Fascism and the ‘problem’ of post-war reconstruction and social reform whilst ignorant of the presence of a Nazi at their dining table. The wolf is no longer at the door but is instead sitting at the dining table, eating a meal and conversing with that bastion of modern civilisation, the small town family. Where Shadow of a Doubt imports the ‘madness’, violence and criminality of city life into the ‘seeming innocence and purity’ of its small town setting, The Stranger imports the threat of Nazi ideology into the small town of Harper, Connecticut (Freedman & Millington, op cit.: 4).  In The Films of Alfred Hitchcock (1993), David Sterritt draws some direct comparisons between Shadow of a Doubt and The Stranger, suggesting that both ‘Uncle Charlie’ and Franz Kindler are ‘compared visually with vampires’: this is most overt in Shadow of a Doubt, but in The Stranger this occurs most vividly during the sequence in which Kindler throttles Meinike, lowering the man’s body into a bush in a manner that recalls Bela Lugosi’s approach to his victims in Dracula (Tod Browning, 1931) and, later in the film, when Kindler’s shadow is cast over Mary as she sleeps (58). Both Shadow of a Doubt and The Stranger also feature villains who have ‘avoided being photographed’ and women who ‘fail to go to the authorities’ even when ‘an authority is nearby and eager to be gone to’ (ibid.). Furthermore, both Shadow of a Doubt and The Stranger share characteristics of films noirs but avoid the typical urban setting of the films noirs of the 1940s, ‘instead picturing smaller communities as infected, traplike places’ (ibid.).  In its critique of small town life (and the parochial mentality with which it is associated) and the perceived complacency towards the threat of Nazism that followed the Second World War, The Stranger has some interesting thematic content, especially for a film that Welles himself once described as ‘lead-footed’ (Welles, quoted in Christopher, 1997: 70). Welles deliberately delivered the film as a ‘linear, plot-driven’ picture so as to show that he could direct a conventional thriller and thereby ‘prove himself “marketable” to his Hollywood overlords’ (ibid.; see also Heylin, 2005: 169). In the words of the film’s editor Ernest Nims (interviewed in American Cinemeditor), at the time Welles ‘had a reputation of being a very costly and rather unmanageable director’ and ‘was very anxious to correct this impression’ (Nims, quoted in Heylin, op cit.: 175). Welles himself once suggested that he agreed to make the film ‘to show people that I didn’t glow in the dark—that I could say “action” and “cut” just like all the other fellas’ (Welles, quoted in ibid.: 171). However, although Welles managed to shoot The Stranger under budget (and one day under schedule), in postproduction the producers reputedly cut twenty minutes of footage set in South America, in which Meinike tries to discover the whereabouts of Kindler before being directed to the town of Harper (see Fitzgerald, 2000: 78; Heylin, op cit.: 176). Despite Welles’ attempts to deliver a conventional and therefore bankable thriller, The Stranger was commercially unsuccessful; following its release, Welles retreated from filmmaking into theatre. However, after getting into debt with his stage production of Around the World in 80 Days, Welles’ negotiated with producer Harry Cohn to direct The Lady From Shanghai (1947), a film which openly lampoons the conventions of the then-popular films noirs and which precipitated Welles’ disengagement from Hollywood: following The Lady From Shanghai, Cohn declared that Welles found it impossible to deliver a film on schedule and within budget, and Welles’ subsequent films were made outside the Hollywood system. Prior to the production of The Stranger, Welles had shown an interest in the nature of Fascism and, especially, the documentary footage of the liberation of the concentration camps; writing in his column for The New York Post, Welles stated that this documentary footage ‘must be seen’ as an index of the ‘putrefaction of the soul, a perfect spiritual garbage’ associated with what ‘we have been calling […] Fascism. The stench is unendurable’ (Welles, quoted in Heylin, 2005: 163; emphasis in original). Welles managed to work some of these preoccupations into the film: the film openly engages with the fallout of Fascism, and in one striking scene Mr Wilson shows Mary Longstreet some filmed footage of the concentration camps. Mary sits in stunned silence, and Welles holds the camera on a close-up of Loretta Young as the light from the projector flickers across her face.  In his New York Post columns, Welles openly declared that he felt the social reforms taking place in post-war Germany would not eradicate the spectre of Fascism: he stated that those subscribing to Nazi ideology were ‘laying the fuel for another conflagration [….] Stealthy as before and shrewd as ever, the Nazis of 1932 are plotting for 1952’ (ibid.: 165). Written in association with John Huston, The Stranger offered Welles an opportunity to explore this issue in a very direct manner. During one of the film’s strongest scenes, Mr Wilson and Kindler (as Rankin) join the Longstreets for dinner. The topic of conversation turns to an article about the social reforms that are taking place in post-war Germany and the existence of underground cabals of Nazi supporters. Mary’s brother Noah Longstreet (Richard Long) declares disbelievingly that ‘I think it’s ridiculous: no German in his right mind can still have a taste for war’. In response, Welles (as Kindler, a character who has already established his still-existing Nazi ideology) delivers a monologue that offers a critique of complacency in the face of Fascism: ‘The German sees himself as the innocent victim of world envy and hatred, conspired against, set upon by inferior peoples [and] inferior nations. He cannot admit to error, much less to wrongdoing [….] [T]he German […] still follows his warrior gods, marching to Wagnerian strains, his eye still fixed upon the fiery sword of Siegfried; and in those subterranean meeting places that you don’t believe in, the German’s dream world comes alive and he takes his place in shining armour, beneath the banners of Teutonic knights. Mankind is waiting for the Messiah, but for the German the Messiah is not the Prince of Peace: he’s another Barbarossa, another Hitler’. When Wilson says that Kindler/Rankin can therefore ‘have no faith in the reforms that are being effected in Germany’, Kindler/Rankin states that ‘I don’t know, Mr Wilson. I can’t believe that people can be reformed, except from within’ and suggests that the only solution is ‘Annihilation… to the last babe in arms’. Shocked, Mary declares that ‘I can’t believe you’re advocating a Carthaginian peace’, to which Kindler/Rankin responds by asserting that ‘as a historian I must remind you that the world hasn’t had much trouble from Carthage in the past two thousand years’. In this sequence, the film offers a direct critique of complacency and the notion of social reform that echoes the sentiment of Welles’ New York Post columns on the topic of Fascism. Although Welles never directly suggested that the Nazism could be quelled by nothing other than a ‘Carthaginian peace’, his cynicism about the notion of social reform seems to be echoed in Kindler/Rankin’s monologue. However, in the film the sentiment is given irony by the fact that it is delivered by a man, Kindler, who himself is a Nazi; but as the opening sequence suggests, Wilson shares some of Kindler’s ideas—Wilson is established in the opening minutes as a maverick who has little time for established procedures and is willing to bend the rules in order to achieve his goal, releasing Meinike against the will of the other members of the commission, in order to discover the whereabouts of Kindler. Wilson declares to his colleagues, ‘What good are words? I’m sick of words’, before asserting that ‘this obscenity [Kindler] must be destroyed’. However, fittingly for a Welles picture (which rarely offer ‘easy’ solutions to complex problems), within the film there is a recognition that violence begets violence: reflecting on his murder of Meinike, which has necessitated the killing of the Longstreet’s dog Red and may culminate in the murder of Mary, Kindler asserts that ‘Murder can be a chain […]: one link leading to another until it circles your neck’. The claims that this is a film which does not carry Welles’ signature hold some water, although there are traces of Welles’ directorial voice here: this is evidenced in such devices as the use of overlapping dialogue during a party sequence, Welles’ trademark use of high angle close-ups and some ironic editing (for example, in the cross-cutting that takes place between Meinike’s attack on Wilson and Kindler’s marriage to Mary Longstreet). It is a fine example of the form of the film noir and features strong central performances by Robinson, Welles and Loretta Young. It’s certainly a more conventional and less eccentric film than Welles’ other films noirs, The Lady From Shanghai and Touch of Evil (1958). However, The Stranger is thematically rich in its exploration of the social fallout of Nazism and its deconstruction of small town life—which, as noted above, allies it with Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt. Although it is seen as one of Welles’ lesser films, a ‘lesser film’ by Welles is still worth a viewer’s investment of time and money. The film runs for 94:55 (PAL) and is uncut. Unlike many of Welles' other films, there are no variant edits: this is the only edit of the film in existence.

Video

The Stranger is presented in its original Academy aspect ratio of 1.33:1. Picture quality is more than adequate, although it’s a little soft at times. The blacks are rich and there is strong gradation in the greys. In terms of the visual presentation of the film, this disc is certainly a big improvement over the French DVDY Films release, but it’s a little less impressive than the barebones R1 release from MGM. Network’s DVD:

DVDY Films’ DVD:

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel mono track. Dialogue is always clear and there are no problems with this audio track. There are no subtitles.

Extras

The sole extra is a trailer (1:53). The trailer frames the film as a ‘strange love story’ about ‘strange people with a startling secret’: it’s a classic trailer for a suspense melodrama, drawing attention to the film’s small town setting and the theme of family deceit; but it neglects to mention the film’s exploration of Nazism.

Overall

Although not one of Welles’ most highly-regarded films, The Stranger is still a rewarding experience. Network’s presentation of the film is good, and the disc is competitively-priced. For more information, please visit the website of Network DVD. References: Christopher, Nicholas, 1997: Somewhere in the Night: Film Noir and the American City. New York: Simon & Schuster Fitzgerald, Martin, 2000: The Pocket Essential Orson Welles. Hertfordshire: Pocket Essentials Freedman, Jonathan & Millington, Richard, 1999: ‘Introduction’. In: Freedman, Jonathan & Millington, Richard (eds), 1999: Hitchcock’s America. Oxford University Press: Pp.3-14 Heylin, Clinton, 2005: Despite the System: Orson Welles Versus the Hollywood Studios. Edinburgh: Canongate Books, Ltd Michie, Elsie B., 1999: ‘Unveiling Maternal Desires: Hitchcock and American Domesticity’. In: Freedman, Jonathan & Millington, Richard (eds), 1999: Hitchcock’s America. Oxford University Press: Pp.29-54 Sterritt, David, 1993: The Films of Alfred Hitchcock. Cambridge University Press

|

|||||

|