|

|

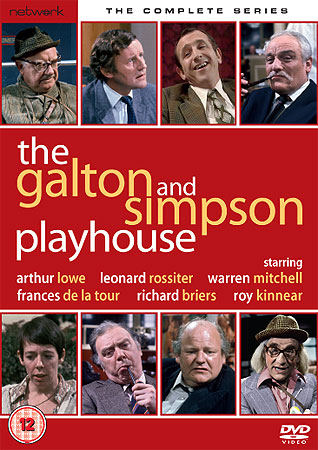

Galton and Simpson Playhouse (The)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (16th January 2009). |

|

The Show

Yorkshire Television, 1977 Seven episodes: 'Car Along the Pass' (25:17) 'I'll Swap You One of These for One of Those' (23:46) 'Cheers' (22:23) 'Naught for Thy Comfort' (24:13) 'Variations on a Theme' (24:30) 'I Tell You It's Burt Reynolds' (25:11) 'Big Deal at York City' (24:43)

Ray Galton and Alan Simpson are most famous for their work on the BBC’s situation comedies Hancock’s Half-Hour (1956-60), Hancock (1961) and Steptoe & Son (1962-1974). Like the work of Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais (Porridge, BBC 1974-7; The Likely Lads, BBC 1964-6; Whatever Happened to the Likely Lads, BBC 1973-4), Galton and Simpson’s work is known by its sense of pathos. Like Clement and La Frenais’ sitcoms, Galton and Simpson’s humour is often bittersweet: in Steptoe & Son, the bickering between Harold Steptoe (Harry H. Corbett) and his father Albert Steptoe (Wilfrid Brambell) is the show’s source of comedy but is made bittersweet by the fact that the characters are trapped within an existence that is making them increasingly bitter, Harold’s aspirations for a better life (through education, through finding new employment, through finding love) thwarted at every step by society’s expectations of his behaviour as a working-class man and by his responsibility for his father. As John Oliver’s biography of Galton and Simpson on the BFI’s ScreenOnline website notes, ‘working not with comedians or comic actors but with two straight actors, Harry H. Corbett and Wilfrid Brambell, they created a sitcom that was often as achingly poignant as it was funny. The two main themes of male love/hate relationships and the thwarted desire for self-advancement were familiar from the Hancock scripts, but they were elevated here to a dramatic level that would have been impossible with comedians in the lead roles’ (Oliver, Year Unknown: np). By the late-1960s, Galton and Simpson had become known to the British public to the extent that their names were a saleable commodity, as evidenced through London Weekend Television’s decision to give their series of six one-off comedies the title The Galton and Simpson Comedy (LWT, 1969). This approach was revised in 1977 for The Galton and Simpson Playhouse, produced for Yorkshire Television and broadcast on ITV.

The Galton and Simpson Playhouse encompassed seven episodes focusing on different comic situations. All of these situations have a bittersweet edge to them, something which characterises British situation comedies as different from US sitcoms. In his book on The Likely Lads (2008), Phil Wickham suggests that this difference began with Tony Hancock’s character in Hancock’s Half-Hour: ‘From this moment on, much of British sitcom has had a rather dark hue. Either it features characters that are less than likeble (Basil Fawlty, Alf Garnett, or Rigsby) or those that for all their good intentions were destined to fail (Harold Steptoe or Captain Mainwaring)’ (85). Where US sitcoms tend to focus on ‘glamorous showbiz lifestyles or swanky apartments’, ‘British audiences seem to respond to the shabby everyday rather than idealised luxury or comfort […] British sitcoms have [therefore] relied on the familiar, the down at heel, for laughs; the factory floor, the suburban semi, the failing seaside hotel, the market stall’ (ibid.).

US sitcoms have traditionally been produced in bulk, with each series containing a high number of episodes, which necessitates the use of ‘writing teams’; ‘this has led to a reliance on the gag, and the tough commercial environment’ that exists in the US ‘means that the audience have to be made to laugh as much as possible to illustrate that the show is a success’ (ibid.: 86). Conversely, British sitcoms feature series with less episodes and therefore can be produced by either individual writers or writing pairs (Galton and Simpson, or Clement and La Frenais); thus the shows are defined by the input of a limited number of writers and there is more space for the writers to author their sitcoms, injecting them with their own specific concerns or tone—‘British sitcom writing is then defined by the characters within the situation and the tone of its author[s]’ (ibid.). Furthermore, the fact that the UK marketplace has until recently been less competitive than it is in the US means that British sitcoms could be bittersweet: there was not the need to make the audience ‘laugh as much as possible to show that the show is a success’, thus following the model set by Galton and Simpson even the most recent British sitcoms have tended to be rather downbeat and not overloaded with ‘gags’ (Black Books, C4 2000-2004; Father Ted, C4 1995-1998; Peep Show, C4 2003- ; The Office, BBC 2001-2003). However, with the growth of free-to-view multichannel television in the UK and the success of imported US sitcoms such as Friends (NBC, 1994-2004) this may change in the near future; still, the traditional British bittersweet sitcom can be seen in current sitcoms such as Not Going Out (BBC, 2006- ), Saxondale (BBC, 2006- ) and Lead Balloon (BBC, 2006- ). The stories in these episodes of The Galton and Simpson Playhouse are typical of the bittersweet British situation comedy, revolving around xenophobic British tourists (‘Car Along the Pass’), middle-aged men obsessed with the idea of having affairs with younger women but who are forced into the realisation that they simply aren’t ‘up to it’ (‘I’ll Swap You One of These For One of Those’) and men whose relationships have collapsed, leaving them with a sense of self-loathing and a desire to heap their burden upon their friends and families (‘Naught For Thy Comfort’).  Henry Duckworth (Arthur Lowe) and his wife Ethel (Mona Washbourne) are holidaying in the Swiss Alps. Henry complains that the holiday has been too expensive: ‘Worst holiday I’ve ever had. We both spent over £18 each’. When his wife tells him ‘I enjoyed it’, Henry responds by declaring, ‘Well, you would: you weren’t paying for it’. When the cable car they are travelling on becomes stuck due to a power failure, the xenophobic Duckworth tries to take charge of the situation (in the same manner as Tony Hancock in ‘The Lift’, the classic 1961 episode of Hancock). Duckworth is obsessed with status and class, and becomes embroiled in a game of one-up-manship with the German former-Luftwaffe squadron leader (played by Anton Diffring) sitting next to him; when the German declares ‘I love England’ and reveals that before the war he attended an English public school, Duckworth consistently reminds the other man of Germany’s role in the Second World War and tries to convince the German that he also attended a public school (although Duckworth’s wife reveals that her husband actually attended a grammar school). When the other British man on the cable car (played by Aubrey Morris) begins to blab ‘I don’t want to die’, Lowe declares ‘He’s not really British, this one. Naturalised [….] Just because we’re in the common market doesn’t mean we have to behave like them’. It’s easy to imagine Duckworth as a character played by Tony Hancock in Hancock’s Half-Hour. Duckworth is the type of snobbish xenophobe that Tony Hancock typically revelled in playing: after correcting a minor grammatical mistake made by the polite German traveller on the cable car, Duckworth declares that ‘I always make a point of correcting foreigners, otherwise they never learn’. Later, he says that the situation has ‘One consolation, of course: if we do fall 10,000 feet to our death, most of the dead will be foreigners’.  Henry (Richard Briers) is a married middle-aged man who discovers that he has a wandering eye; but when your secretary is none other than Linda Hayden, in all honesty who can blame you? Henry expresses his concerns at the ‘nubile girls wandering around the office’. However, he tries to convince himself that he’s ‘not the slightest bit interested’. Later, he tries to persuade his secretary to have an affair with him: ‘What’s the use of having a tin opener if you can’t go shopping’, he tells her. Henry’s colleague Gresham (Henry McGee) suggests that Henry find himself a mistress. When Henry expresses concern over finding a mistress that takes his fancy, Gresham tells him, ‘Don’t worry about their faces: you don’t look at the extractor fan when you’re putting your dinner in the oven’. Eventually, Gresham persuades Henry to attend a swingers’ party with his wife. Henry asks if he can go on his own, but Gresham responds negatively—his wife is his ‘entrance fee’. However, when Henry arrives at Gresham’s party without his wife (who has lost her way), he is refused admission. The otherwise funny episode comes to quite a tragic conclusion, as Henry’s wife eventually arrives and is admitted to the party but Henry spends the night drunk and on the doorstep of Gresham’s flat. This episode is a reworking of an unused script for Galton and Simpson’s risqué series Casanova ’73: The Adventures of a 20th Century Libertine (BBC, 1973), where the character of Henry had been played by Leslie Phillips.  In this episode, Charles Gray and Freddie Jones play two bachelors, lifelong friends who have entered into a life of mundane ritual. Their relationship is a parody of a marriage (like the relationship between Bob and Terry in The Likely Lads, or between Tony Hancock and Sid James in Hancock’s Half-Hour.) The episode takes place in a pub. Charles (Gray) instantly knows something is wrong when his friend Peter (Jones) orders a Tequila Sunrise instead of his usual Pink Gin. Peter reveals that he is getting married on Saturday, to which Charles declares ‘You can’t get married on Saturday, because we’ve got the laundrette to do’. Peter has tired of their ritualistic life together, telling Charles his marriage is ‘for the best. We’ve been together far too long. Living in each other’s pockets, always seen together. As it is, people think we’re a couple of puffs’. Charles tells him, ‘I don’t believe it; I don’t look anything like a puff’; to this, Peter replies, ‘Do you know what they call us in here? Pinky and Perky’. Peter highlights for Charles the nature of their relationship when he says, ‘You are not my wife’. However, Charles has different ideas: ‘No, I am not your wife. But it amounts to the same thing… apart from sex. We agreed years ago that women would not enter into our lives, apart from our occasional weekends in Amsterdam’. The episode parodies the sexless ‘men without women’ lifestyle of these two bachelors: as Charles says, ‘Just because a chap doesn’t like women, doesn’t mean to say he’s a puff. I wasn’t a puff at Dunkirk, was I?’ Peter reminds him that, ‘One or two of them were. Remember that brigadeer standing near us? When the shell came and blew his uniform off, he had ladies’ underwear on underneath it’. As in much of Galton and Simpson’s work, the suggestion that the monotony will be broken and the characters will be allowed to grow and develop into new patterns of behaviour is frustrated during the closing moments of the episode; in its use of this structure, this is the episode that most closely resembles Galton and Simpson’s work on Steptoe & Son (or the work of their model, Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting For Godot.) Much of the comedy in this episode is sourced from word-play and the way in which the characters parrot each other’s words.  Roy Kinnear plays Richard Burton, an airline purser. Upon returning from a trip to the continent, Burton unpacks his bag full of duty free goodies, cigarettes and a bottle of Johnnie Walker Red Label; upon opening the cupboard in his sitting room, we are shown that he already has more than enough bottles of Johnnie Walker and packets of cigarettes than he would need to open a shop–immediately, we are told that like many of Galton and Simpson’s creations, Burton is a man of habit and comforting rituals. After engaging in a monologue to his wife, who he assumes to be upstairs, Burton finds that his house is in fact empty; upon exploration, he discovers a note telling him his wife has left him. Trying to uncover where his wife might be, Burton telephones his wife’s mother: ‘She’ll know where she is. She knows where everyone is. She even knows where Martin Bormann is, the nosy cow’. Burton’s mother-in-law claims not to know where his wife is but accuses Burton of holding his wife back: ‘It’s not what you’ve done to me; it’s what you did to her. Ruined her life. You didn’t only take her away from me; you took her away from BOAC. I’ll never forgive you for that. She had a career ahead of her; she spoke another language’. To this, Burton retorts, ‘So did you, until you moved out of Grimsby’. Seeking solace, Burton telephones his friend Harry, who avoids him; then he seeks consolation at a pub but finds only an unsympathetic landlord. Deciding to telephone a call-in show, Burton is dismissed because the DJ thinks that it’s a prank call, due to the caller’s name (Richard Burton) and his declaration that ‘My wife’s left me’. Finally, Burton tries to gas himself in the oven but realises that his wife has replaced their gas oven with an electric stove. Burton is a another typical Galton and Simpson tragic protagonist: like Hancock or Harold Steptoe, he is not particularly sympathetic (in fact, even his ‘friends’ don’t particularly like him) but is pitiable both because of his situation and because of the lack of social support that he has. The irony within this episode is that at every turn, Burton discovers people who are in a worse bind than himself but he is so wrapped up in his own problems that he can’t engage with these other people and expects them to console him.  Frances De La Tour and John Bird play a couple who meet at a bench in a park. De La Tour greets Bird with the declaration, ‘Robert’s found out’. The gimmick in this episode is that the same set-up is repeated after the break bumpers as the introduction to a different narrative. In the first half of the episode, De La Tour’s declaration refers to the fact that her husband (Robert) has discovered that she and Bird are having an affair. They try to find some sort of resolution to their problem. Bird uses his experience as an advice columnist in the local newspaper to try to persuade De La Tour to forget about him and return to her husband. Eventually, De La Tour persuades Bird to write out a check for £5,000 to ‘restore his [her husband’s] honour’ and to avoid Bird being mentioned in the divorce proceedings. Bird leaves, and De La Tour moves to the next bench, where she meets another man with whom she has been having an affair and from whom she clearly intends to swindle another £5,000. In the second half of the episode, following the break bumpers, the same set-up is repeated (the park bench, the claim that ‘Robert’s found out’) but this time Bird and De La Tour play a married couple, and De La Tour’s declaration refers to their son Robert’s discovery of the world of sex; the story is about Bird’s failure to tell their son (Robert) about the ‘birds and the bees’. This episode is admittedly quite clever in its structure, and Bird and De La Tour turn in good performances in what is essentially a ‘two-hander’. However, the episode simply isn’t as funny as any of the other episodes in the series. There isn’t a clearly identifiable archetypal Galton and Simpson protagonist here, and possibly as a result there doesn’t seem to be much investment in the characters’ dilemma.  Beginning in a family home, the disruption in this episode occurs with the arrival of Uncle Jim (Leonard Rossiter). As Jim makes his presence known, the kids go upstairs and the other family members prepare themselves: it is clear that they find Jim abrasive. Upon entering the sitting room, Jim immediately offends the lodger Eric by accusing him of being lazy (‘Are you still “resting”, as they say in your profession?’) and then moans that ‘You could die of thirst in this house’. The family are watching an episode of McMillan and Wife on the television; paying attention to the screen, Jim asks ‘What’s Burt Reynolds doing in a film like this?’ The rest of the characters argue with him, stating that Jim is mistaken and the bit-part actor is not Burt Reynolds. (The gran says, ‘That’s not Debbie Reynolds’.) Asserting his knowledge of Burt Reynolds’ career (‘How many years have I been going to the pictures? I mean, I’ve seen every film that Burt Reynolds has ever made’), Jim makes a bet that Reynolds was in the episode of McMillan and Wife and goes to great lengths to prove that he’s right, telephoning Yorkshire Television (whose channel the episode was shown on), a national newspaper and, finally, Burt Reynolds himself. This is a gem of an episode. Delivering a pitch-perfect performance that verges on the point of hysteria when he is under threat of being proven wrong, Rossiter here demonstrates that he is one of Britain’s best comic performers. As Uncle Jim, he plays a typically boorish Galton and Simpson protagonist. It would be interesting to see how this episode plays to a younger audience, as today these kinds of once-all too familiar debates would be settled by simply searching for the episode’s cast list on the Internet.  In this episode, Warren Mitchell plays a gambler who is returning home on a train after a ‘good day’ at York racetrack. Sitting in a carriage, drinking beer and brandy miniatures, Mitchell soon finds the carriage filled with all manner of characters, including a bishop. Soon, Mitchell has persuaded the other members of the carriage to begin a little gambling clique, and has even encouraged the bishop to participate in a game of cards. However, the jollity of Mitchell’s day may be about to be undercut. This episode is a step down from the comic heights of the previous story. However, Mitchell’s character is well-observed and there are some good one-liners.

Video

The episodes are presented in their original aspect ratio of 4:3. Quality is very good, although the series is mostly studio-bound and therefore shot on videotape rather than film. The original break bumpers are intact, and the episodes are uncut.

Audio

Audio is presented via two-channel monophonic sound; the audio track is clear and problem free. Dialogue is always audible. There are no subtitles.

Extras

There are no extra features.

Overall

If anything, this series confirms that Galton and Simpson’s work is strongest when it deals with the types of boorish outsiders that populate their most famous work, from their scripts for Hancock, Hancock’s Half-Hour and Steptoe & Son. The episodes that deviate from this formula (‘Variations on a Theme’, for example) are the weakest, whilst the strongest episodes are those that maintain their focus on boorish middle-aged men (‘Car Along the Pass’, ‘I’ll Swap You One of These For One of Those’, ‘I Tell You It’s Burt Reynolds’).

Possibly the strongest episode in this set is ‘I Tell You It’s Burt Reynolds’, thanks in large part to Leonard Rossiter’s performance as the bull-headed Uncle Jim. As with Rossiter’s work as Rigsby in Rising Damp, in this episode Rossiter perfectly nails Uncle Jim’s moral indignation, not to mention the subtle suggestions (via physical tics and the introduction of a shrill tone in his voice) of a sense of panic that signifies the character’s realisation that he may be wrong, but which only serves to reinforce his stubborn declaration that it was indeed Burt Reynolds that he saw in a bit-part on McMillan and Wife (perhaps more as a means of convincing himself that he’s right than anyone else). The strength of Jim’s assertion on such a petty issue is an index of the same kind of existential panic that makes Galton and Simpson’s Steptoe & Son so bittersweet; in the case of both Uncle Jim in ‘I Tell You It’s Burt Reynolds’ and Harold Steptoe (Harry H. Corbett) in Steptoe & Son, the habit of blowing trivialities out of all sense of proportion is the characters’ means of dealing with their banal existence and the awareness of the wasted nature of their lives. Galton and Simpson’s humour is largely a comedy of the absurd, and it’s for this reason that Harold and Albert Steptoe (Wilfrid Brambell) have often been compared to Vladimir and Estragon in Samuel Beckett’s absurdist Waiting For Godot. (According to the BBC4 2008 drama The Curse of Steptoe, Harry H. Corbett—then a renowned theatre actor—was convinced to take the ‘lowly’ role of Harold Steptoe in a television sitcom due to Steptoe & Son’s similarity to Beckett’s work; in the drama, he enthusiastically comments on the first script of the sitcom, ‘It’s practically Beckett’.) In light of this, it’s a shame that Rossiter did not produce more work with Galton and Simpson, as these are the kinds of characters at which he excelled. Aside from the odd weak episode, this series comes with a strong recommendation. 'I Tell You It's Burt Reynolds' is almost worth the asking price alone.

References Goodwin, Cliff, 1999: When the Wind Changed: The Life and Death of Tony Hancock. London: Arrow Oliver, John, Year Unknown: ‘Galton, Ray (1930-) and Simpson, Alan (1929-)’. [Online.] http://www.screenonline.org.uk/people/id/467108/ Date accessed: January 2009 Webber, Richard, 2004: 50 Years of ‘Hancock’s Half Hour’. London: Arrow Wickham, Phil, 2008: BFI TV Classics: ‘The Likely Lads’. London: British Film Insitute For more information, please visit the homepage of NetworkDVD.

|

|||||

|