|

|

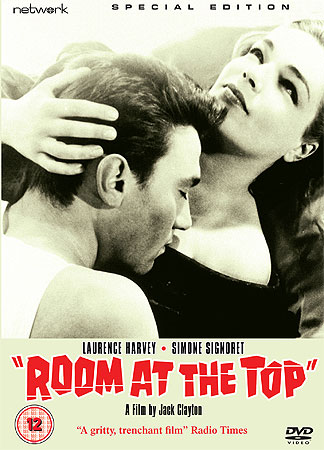

Room At The Top

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (24th January 2009). |

|

The Film

Room at the Top (Jack Clayton, 1958) begins with a train journey. Over a black screen, a train’s whistle screeches; a man’s feet, clad in worn socks, are shown in close-up, perched on the table that separates two seats in a passenger train car. Through the window, the landscape of industrial Britain passes by: a gasworks and its belching chimneys, followed by row upon row of Victorian terraces. The camera pans along the man’s body; his face is obscured by a copy of The Daily Telegraph, from behind which he blows smoke rings. The man lowers the newspaper to look out of the window before putting on his new suede shoes. The man is Laurence Harvey, an actor who would become iconic of 1960s British cinema and, especially, ‘kitchen sink’ dramas for his role in this adaptation of John Braine’s 1957 novel. Harvey plays Joe Lampton, a twenty five-year old man from a working class background in the small Yorkshire town of Dufton. As the film opens, Lampton is travelling via train to Warnley, where he has secured a new job. Lampton makes a new friend, Soames (Donald Houston), and makes his ambition clear. Soames takes Lampton to the local amateur dramatics society, where Lampton watches a play and develops an interest in one of the performers, Susan Brown (Heather Sears). However, Susan is the daughter of the local industrialist, and Lampton’s interest in Susan is hampered both by Susan’s family, who display open snobbery towards Joe’s background, and Lampton’s friends and family, who warn Joe to ‘Stick to your own people’.  A former prisoner of war, Lampton comes into conflict with another former POW, Jack Wales (John Westbrook). Wales also has eyes for Susan; and when Joe takes steps to court Susan, Wales becomes more openly antagonistic. Joe’s burgeoning relationship with Susan is hampered by the interference of Wales and Susan’s family, and Joe seeks solace in the arms of a French woman, Alice Aisgill (Simone Signoret). However, Alice is ten years older than Lampton, and she is also married. Alice and Joe’s relationship is thwarted when Alice’s husband finds out and threatens her with divorce, and Joe’s life is further complicated when it is revealed that Susan is pregnant with his child. Setting the template for the ‘kitchen sink’ pictures that followed in its wake, Room at the Top takes as its central focus the theme of class conflict. Like many of the British ‘new wave’ films that appeared in the following years, Room at the Top also transgressed taboos in terms of its representation of sexuality and language; writing in the Daily Express, the critic Leonard Mosley called the film ‘savagely frank and brutally truthful’ (Mosley, quoted in Lowenstein, 2000: 224). As played by Laurence Harvey, Joe Lampton is an ambitious and lustful young man, who despite the advice of his friends and family believes that the barriers of social class can be transcended. During his first meeting with Soames, Lampton gazes through the office window, watching Susan climb into an Aston Martin belonging to Jack Wales. Noticing Lampton’s interest in Susan, Soames jokes, ‘Is that what you really want, a clerk’s dream; a girl with a Riviera tan and a Lagonda?’ With deadly seriousness, Lampton responds by stating ‘That’s what I’m going to have’, although it’s unclear whether Lampton desires the ‘girl with the Riviera tan’ more than the Lagonda. Later, When Joe returns to Dufton and visits his family he is advised by his uncle to ‘Stick to your own people, Joe’. To this, Joe snaps back, ‘Oh, that’s old-fashioned, all that class stuff. Things have changed since the war. If I want her, I’ll have her’. When, in response, he is asked ‘Are you sure it’s the girl you want, Joe; not the brass?’, Lampton responds by stating, ‘What’s wrong with wanting both?’   However, despite his desire to make it to ‘the top’, Lampton also expresses extreme distaste for those who have been born with the privileges to which he never had access. In an intimate scene with Alice, who needles Joe about his antagonistic relationship with Wales, Lampton asserts strongly, ‘That type, they make me mad: the boys with the big mouths and the silver spoons stuck in them. They think they can take everything worth having by a sort of divine right’. However, Joe is equally guilty of thinking that he ‘can take everything worth having by a sort of divine right’, both in his social ambitions and in his attempt to carry on his affair with Alice whilst also intermittently courting Susan. Joe sees Wales as his enemy because Wales represents a more privileged reflection of himself; both of them were captured during the war, but where Joe remained a POW until the end of the conflict, Wales managed to escape. When Alice provocatively asks Lampton ‘Why didn’t you have the guts to escape like Jack Wales?’, Joe angrily asserts, ‘Don’t mention that swine’s name to me. It was alright for him to escape: he had a rich father to look after him and buy him an education. Those three years were the only chance I’d get to be qualified. Let those rich bastards who have all the fun be heroes; let them pay for their privileges. If you want it straight from the soldier, I was bloody well pleased when I was captured. I didn’t like being a prisoner, but it was a damn sight better than being dead’. He finishes his rant with a spiteful dig at Alice’s age, asking her ‘Come to that, what did you do fifty years ago, back in the Great War?’   The class conflict in the film is also signified through a regional conflict. The small town of Dufton, from which Lampton hails, is seen as a poor reflection of Warnley and is discussed in deeply patronising tones. When Dufton first arrives in Warnley, his new employer (Raymond Huntley) tells him, ‘You’ll meet a different class of people. We pride ourselves on being civilised here in Warnley’. In response to this, Lampton reminds his employer that ‘Dufton’s not much of a place, but we’re not exactly savages there, Mr Hoylake’. Nevertheless, Lampton is not above criticising his home town, and in one scene he asserts that ‘Nobody ever goes to Dufton; they just pass through it. A Sunday treat of fish and chips, wrapped in a greasy News of the World’. In another sequence, Lampton explains the way in which he sees Dufton as a trap, a place that ensnares the people who live in it: ‘When I was a POW, there was a limit to the time you served; but Dufton felt like a lifetime sentence’.  Susan’s mother (Ambrosine Phillpotts) disapproves of Lampton in a way that suggests less-than-veiled snobbery about Lampton’s background, referring to Joe as a ‘small-town nobody’. However, we are also reminded that Susan’s father (Donald Wolfit), a self-made man, comes from a modest background: in response to his wife’s comment, Mr Brown reminds her that ‘Small-town nobodies sometimes do well enough. You saw nowt wrong with one once’. The film establishes that Lampton and Mr Brown have more in common than they may like to admit. When Mr Brown invites Lampton to the local Conservative Club and asks ‘First time you’ve been in this club, is it?’, Lampton declares ‘This or any other Conservative Club. My father would turn in his grave if he could see me now’. Brown sympathetically asserts, ‘So would mine. But we’re not bound by our fathers’. By the end of the film, Lampton will find himself at the end of a journey that has led him to adopting the traits of his class enemy, Jack Wales.  Braine’s novel had been published in 1957, but it was set during the late-1940s. Clayton’s film adaptation is clearly set in the late-1950s, which makes the narrative’s timeline somewhat idiosyncratic: if the film is set in a time contemporaneous with its production (ie, in 1958 or thereabouts), it is impossible for Lampton (who, as stated through the dialogue, is twenty-five years old) to have been held as a prisoner of war by the Germans: at the end of the war, Lampton would have been no more than twelve or thirteen at most. Nevertheless, the film tackles the issue of the social fallout of the Second World War through its exploration of the antagonistic relationship between Lampton and Wales, and in focusing on very real social issues the film marked a seismic shift away from the then-dominant themes of British cinema. In his monograph on the films of director Jack Clayton (2000), Neil Sinyard states that ‘[m]ade during the year when film production was ceasing at Ealing, [Room at the Top] seemed symbolically to displace an Ealing tradition of gentility and restraint and raise the whole emotional temperature of British film’ (37). Room at the Top ushered in the British ‘new wave’ of ‘angry young’ filmmakers; but unlike many of the other directors associated with the ‘kitchen sink’ tradition (Tony Richardson, Karel Reisz, Lindsay Anderson), Jack Clayton was an ‘industry veteran’ whose earlier films ‘were not exactly portents of revolution’ (ibid.: 38). Thus Clayton’s film is far more conservative than many of the ‘new wave’ films that followed, for reasons that will be discussed shortly. Suffice to say that Clayton disliked the ‘angry young man’ label and thought that ‘young men have always been angry and it was not simply the stagnant social situation of the mid-1950s that was causing them to revolt’ (ibid.: 38).  Atypically for the time, the film was submitted to the BBFC after its completion, as compared with most other films whose scripts were pre-vetted by the BBFC before they went into production (ibid.: 41). The censor objected to ‘a too clinically detailed description of the car crash’ in which Alice is killed and demanded that certain adjectives relating to the outcome of the accident (‘like “scalped”, “crawling about”, “hanging off”, etc’) were removed (Walker, 1974: 50). Several other lines of dialogue were eliminated from elsewhere in the film: ‘“Damn you to hell, you stupid bitch” and “Don’t waste your lust on her.” “Bitch” was changed to “witch” and an alternative line, “Don’t lust after her” was reluctantly approved’ (ibid.: 51). Another sequence, in which Joe seduces a young woman that he meets in a pub, suffered from changes in the dialogue in order to ‘soften […] the bluntness of [Joe’s] approach’ to the girl (ibid.). It’s also perhaps important to remember that, at the time of Room at the Top’s release, the ‘X’ rating was considered to denote a picture that was either a horror film or some form of ‘exploitation fare’ (see Lowenstein, 2000: 224-5).

However, despite its many strengths Room at the Top has suffered from criticism, especially in comparison with the more progressive ‘new wave’ pictures that followed. In Hollywood England (1974), Alexander Walker concedes that ‘Room at the Top (22 January, 1959) was the first important and successful film to have as its here a youth from the post-war working class’ and he also praises the way in which the film, for the first time, gave voice to a regional accent that had been neglected by the cinema, ‘even if it did come and go occasionally’ (45, 46; emphasis in original). In spite of its ‘X’ certificate, Room at the Top achieved commercial success that exceeded the expectations of its producers (ibid.: 50). However, Walker advises that the film’s ‘theme was not a radical one, though: indeed in many ways it was a conservative, almost a reactionary story’ about the dangers of ‘the wish to acquire the values and possessions of the class above, not reject them’ (ibid.: 45). Therefore, unlike many of the ‘new wave’ pictures that followed it, Room at the Top ‘isn’t the stuff of anger or protest’ (ibid.). For Walker, unlike films such as Look Back in Anger (Tony Richardson, 1959) and This Sporting Life (Lindsay Anderson, 1963), the overriding emotion within Room at the Top ‘isn’t anger—but envy—the envy of a have-not for what he wants to acquire’ (ibid.). Lampton’s expression of feeling trapped by his working-class life in Dufton and his attempt to climb the social ladder functioned as a metonym for the ways in which ‘the working-class talents of the 1960s were to merge their own uninhibited attitudes with the life-styles of the affluent world they penetrated’ (ibid.: 46).  Walker also condemns the film’s ‘play[ing] down’ of Joe’s working-class background and identity, focusing more heavily on ‘Joe’s sexuality, not his social origins’ (ibid.: 47). Walker suggests that this was done as a concession to both American audiences and audiences in the south of England, for whom ‘John Braine’s “north country” was foreigh territory’ (ibid.: 46). Contemporary critics also condemned the film, although for different reasons: most of the mainstream critics reacted badly against the film’s open discussion of sexual behaviour. Walker cites the unnamed reviewer in Screen, who compared Lampton to the gardener in D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover (which, in 1958, was still considered to be obscene and had not yet achieved the status of a classic of Twentieth Century literature): ‘Sex is laid on, but mostly it is seedy and not rising to the level of honest passion’ (quoted in Walker, op cit.: 48). More to the point and more in line with Walker’s own criticisms of the film, Nina Hibbin (the critic for the Socialist newspaper the Daily Worker) condemned the film’s focus on ‘an immature, oversexed, unprincipled climber as the main representative of the working class’ (quoted in ibid.).  From the opening sequence, Room at the Top defines social class through its association with various spaces. In ‘“Under-the-Skin Horrors”: Social realism and classlessness in Peeping Tom and the British New Wave’, Adam Lowenstein suggests that the film ‘carefully defines Joe’s class by contrasting his comfort and sense of belonging in certain spaces […] with his awkward exclusion from others’: in the train (‘as it passes through the industrial environs’), Joe’s body language signifies his comfort (his sock-clad feet perched on the table in front of him) and in the ‘outer office’ of the offices at Warnley, Joe finds that ‘the secretaries ogle him’ (226). However, in the ‘private office’ of his new employer Joe is seen to cringe ‘at his boss’s suggestion that the people of Warnley are more “civilised” than those of Dufton’ (ibid.). However, Lowenstein argues that the spaces associated with Joe are left underdeveloped in the film (Joe makes a momentary visit to Dufton in a sequence which lasts no more than a few minutes) and thus the film establishes a distance ‘from him (and from the “working-class” spaces he inhabits’ that ‘bypasses any sort of meaningful social recognition of working-class subjects’, their lives and their problems (ibid.: 227). Echoing Walker’s criticism of the film’s lack of engagement with its working-class subject, Lowenstein concludes that Room at the Top represents social and class conflict but ‘removes the threat of involvement with’ the social changes it depicts, allowing ‘instead for distant, painless contemplation’ (ibid.: 228). Nevertheless, despite the lack of progressive engagement with the issue of social class or questions of poverty (and its animalistic characterisation of its working-class anti-hero), Room at the Top’s cultural importance cannot be underestimated: the film’s focus on class conflict and the lusty, troubled life of its protagonist paved the way for the later, more challenging representations of working-class life that formed the core of the British ‘new wave’.

Video

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.66:1, without anamorphic enhancement. The transfer is clean and sharp, showing off the truly stunning black-and-white photography by Freddie Francis.

Running time is 112:45 mins (PAL).

Audio

The DVD contains a two-channel monophonic audio track, which is clear and problem-free. There are no subtitles.

Extras

The DVD includes an audio commentary by Neil Sinyard, Head of Film Studies at the University of Hull and author of a highly-recommended critical volume on the work of the director Jack Clayton (available from Manchester University Press). Sinyard’s commentary is thoroughly-researched and detailed, and offers much critical insight into the picture—although I may be biased, as I consider Neil to be the one of the best teachers I ever had. Also included is an image gallery (00:59) containing stills from the film.

Overall

Room at the Top is one of the key films from the British ‘new wave’ cinema of the late 1950s and 1960s, and until now the film has only been available in somewhat disappointing DVD versions, which is a shame as this film features some gorgeous cinematography by Freddie Francis. This new release from Network contains a very good transfer of the film and an informative and critical commentary track. For fans of British cinema, this DVD release is a must-purchase. Hopefully, the film’s sequels Life at the Top (Ted Kotcheff, 1965) and Man at the Top (Mike Vardy, 1973) will find their way to DVD soon, along with the Thames Television-produced series Man at the Top (1970). References: Lowenstein, Adam, 2000: ‘“Under-the-Skin Horrors”: Social realism and classlessness in Peeping Tom and the British New Wave’. In: Ashby, Justine & Higson, Andrew (eds), 2000: British Cinema, Past and Present. London: Routledge: 221-232 Sinyard, Neil, 2000: British Film Makers: Jack Clayton. Manchester University Press Walker, Alexander, 1974: Hollywood England: The British Film Industry in the Sixties. London: Orion For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|