|

|

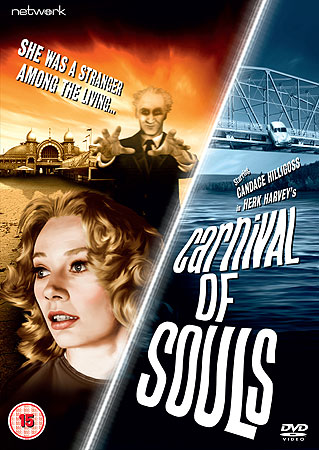

Carnival Of Souls

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (20th February 2009). |

|

The Film

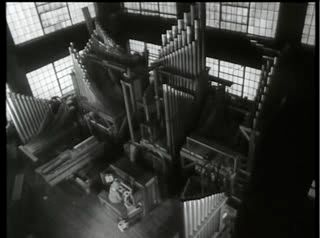

Shot for no more than $30,000 in Lawrence, Kansas and Salt Lake City, Carnival of Souls (Herk Harvey, 1962) was made by a group of Kansas-based filmmakers who, until that point, had been employed by a company named Centron to make industrial and educational films. Making use of Centron’s resources, this group of filmmakers decided to make a narrative feature; after the production of Carnival of Souls, director Herk Harvey returned to making industrial and educational films, never directing another narrative feature. (The transition from the arena of industrial filmmaking to the production of a narrative feature was relatively common within the realm of low-budget independent cinema of the 1960s: both George A. Romero and Herschell Gordon Lewis began their filmmaking careers in the world of industrial and educational film production.) Originally distributed in a heavily-edited version, as the ‘B’ feature on a double-bill with The Devil’s Messenger (Herbert L. Strock, 1961), Carnival of Souls has since its original release acquired a strong cult reputation (see Worland, 2007: 91; Herk Harvey, quoted in Weaver, 1999: 129). For its impact on such films as George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968), The Monthly Film Bulletin once referred to Carnival of Souls as ‘one of the most influential films of the sixties’ (quoted in Cox & Jones, 1993: 6). Opening with a drag race during which one of the cars is accidentally driven off a bridge, Carnival of Souls focuses on one of the female participants in the race, Mary Henry (Candace Hilligoss). In the midst of the ensuing rescue operation, one Mary staggers out of the river, caked in mud. Mary is asked ‘What about the other girl?’ but responds with a simple declaration of ‘I don’t remember’.  Returning to her normal life as an employee in an organ factory, Mary discovers that she has been offered the position of organist at a church in Utah. However, discussing this new job with her boss (Tom McGinnis) she dismisses any possible religious convictions, stating that ‘It’s just a job [….] I’m not taking the vows; I’m only going to play the organ’. Mary is ominously told that ‘it takes more than intellect to be a musician. Put your soul into it’. Ignoring this advice, Mary wanders off whilst declaring portentously, ‘I’m never coming back’. Driving to Utah, Mary notices an old pavilion in the distance. The pavilion is in fact Saltair, ‘[p]art bathing pier, part dance hall, part amusement park’ (Skrdla, 2006: 189). Built by the Mormon Church in 1893, Saltair had, by the early 1960s, fallen into disrepair due to a ‘series of small fires [that] destroyed portions of the complex’ in 1955. More damage was done by a ‘freak windstorm’ in 1957, and in 1958 the pier was finally closed; in 1970, long after the production of Carnival of Souls, a fire completely destroyed the pavilion (ibid.). Shrouded in shadows and looming on the horizon, from its first appearance in the picture Saltair seems to be a mysterious and imposing place. After noticing the pavilion, for the first time in the film Mary sees the ghostly figure (referred to in the credits as ‘the man’ and played by director Herk Harvey) who will haunt her throughout the film. Shocked by his sallow-faced, sunken-eyed appearance, she accidentally drives her car off the road, mirroring the action of the young woman who, during the film’s opening sequence, drove her car off the bridge in Mary’s home town.  Arriving at her destination, Mary talks to the minister (Art Ellison) at the church where she has been employed. She declines the minister’s offer of a reception (‘Couldn’t we just skip that?’, she asks him). The minister tells her that ‘I don’t suppose it’s an absolute necessity’ but expresses concern, telling her that ‘I don’t know what some of the ladies might say’. Mary declares simply that ‘If they say I’m a fine organist, that should be enough, shouldn’t it?’ Reflecting on Mary’s apparent coldness and lack of empathy, the minister reminds her that ‘You cannot live in isolation from the human race’. At her lodgings, Mary meets her sleazy neighbour, John Linden (Sidney Berger), who asks her out for dinner and then harasses her over breakfast the next morning. Discovering that Mary is a church organist, Linden tells her, ‘I didn’t realise you were a church woman’. ‘To me, a church is just another place of business’, Mary replies. When Linden asserts ‘That’s a funny way to look at it’, Mary simply declares ‘I’m a professional organist; I play for pay, that’s all’. However, Linden finds Mary’s dismissal of faith to be disturbing: ‘Thinking like that, don’t it give you nightmares?’  Later that day, whilst shopping Mary discovers that the other people in the department store don’t seem aware of her presence. ‘What’s the matter with everyone? Why don’t they answer me?’, she wonders aloud. Running out of the department store, she stops at a water fountain. Startled by a man who she mistakenly presumes to be the ghoulish apparition that first appeared to her as she passed the ruins of Saltair, Mary runs into the arms of another man (Stan Levitt), who reveals himself to be a doctor and, upon hearing Mary’s story, offers to help her. At his office, the doctor responds to Mary’s hubristic assertions that she’s a ‘realist’ and isn’t prone to imagining things; the doctor asserts that ‘All of us imagine things [….] Our imaginations play tricks on us. They often misinterpret what we see or hear’. When Mary is fired for playing atonal music on the church organ, Linden meets her from work and takes her to a drinking establishment. He is visibly upset that Mary isn’t drinking and enjoying herself: ‘Me, I not only drink really, I really drink’, he tells her; ‘You don’t like to dance and you don’t like to drink; you don’t like for a man to hold you close. That’s it, isn’t it?’ Fearful of the appearance of the ghoul who has been following her, Mary reluctantly invites John into her bedsit. However, John finds her behaviour increasingly strange, and when Mary becomes hysterical after once again finding herself under the surveillance of the ghoul, she frightens John away before screaming ‘I don’t want to be left alone!’ Deciding to leave town, Mary discovers that she can hear only the sound of her own footsteps and the tanoy in the bus depot. Once again, the other people in the bus station do not seem aware of her presence. Fleeing, she finds herself at the old pavilion; there, she sees hollow-eyed ghouls dancing like marionettes in the empty dancehall. Mary has a date with the ghoul who has been following her…  Harvey was inspired to make Carnival of Souls after spotting the dilapidated ruins of Saltair during a drive through Utah (Harvey, cited in Crouse, 2003: 36; Skrdla, op cit.: 189). Inspired by Saltair, Harvey approached the writer (and fellow Centron employee) John Clifford, who within two months had completed a script for the film (Crouse, op cit.: 36). The narrative of the film has often been compared to Ambrose Bierce’s classic short story ‘An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge’ (1890). Bierce’s story takes place during the American Civil War and focuses on Peyton Farquhar, a Confederate soldier who as the story opens is to be hanged by Union troops for his part in a conspiracy to demolish Owl Creek Bridge. At the point of his death, Farquhar appears to escape from the noose and return home, but at the end of the story it is revealed that the escape was an hallucination and that Farquhar has indeed been executed. Despite the overt similarities between Bierce’s story and Carnival of Souls, Clifford claims that at the time that he wrote Carnival of Souls he hadn’t yet encountered ‘An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge’ (see Clifford, quoted in Weaver, 2004: 42). Clifford deliberately wrote the film so that Mary never received any ‘sympathy or understanding from any other character’ (Clifford, quoted in Weaver, 2004: 43; emphasis in original). Because of this, ‘there’s no relief from her dilemma’ (Clifford, quoted in ibid.). However, Mary is a complex character, somewhat distant and aloof. She repeatedly declares that she has ‘no desire for the close company of other people’; this aspect of her character leads Linden, the sleazy neighbour, to assert that she is ‘afraid of men’ and ‘seem[s] so cold’. Writing about the film in his book The 100 Best Movies You’ve Never Seen, Richard Crouse suggests that Mary ‘is a cold, distant character, a break from the stereotypically sympathetic horror movie heroine’ (Crouse, op cit.: 37). This aspect of Mary’s character was deliberate on the part of the filmmakers; Hilligoss was directed by Harvey to play Mary as passive. Interviewed by Tom Weaver, Herk Harvey once noted that ‘Candace kept wanting to get into her role, and for the most part I didn’t want her to get into anything – I just wanted her to sort of walk through it’ (see Harvey, quoted in Weaver, 1999: 133; emphasis in original). Mary’s passivity is what makes her cold and distant; her lack of engagement with the people around her is disorienting for the viewer. As Tom Ruffles notes (in the book Ghost Images: Cinema of the Afterlife), Mary seems to have ‘lost the part of her that makes her an empathic human’ (Ruffles, 2004: 103). As a consequence of her detachment from her social environment, it is unclear if ‘she’s dreaming or somehow projecting, her astral self solid in a shadowy world [sic]’ (ibid.).   When Mary Henry, caked in mud, staggers out of the river after the car accident, she is asked ‘What about the other girl?’ Her response, ‘I don’t remember’, is indexical of the fugue state (an appropriately-named condition for an organist to suffer from) that characterises her later behaviour. This dissociative fugue state is shared by the viewer, as the filmmakers go to great lengths to encourage the audience to empathise with Mary, making the everyday seem threatening through some inventive cinematography. Like Harry Kümel’s La rouge aux lèvres (Daughters of Darkness, 1971) and Jess Franco’s Les Possédées du Diable (Lorna the Exorcist, 1974), Carnival of Souls makes a decaying symbol of the leisure industry, the seaside resort, appear to be threatening. In each of these films, the seaside resort (a place of amusement) is left to decay and becomes a site of horror and dislocation, its once-familiar and comforting architecture made to seem unfamiliar and intimidating. Through the use of odd angles and through emphasising the emptiness of these seemingly abandoned spaces, the filmmakers defamiliarise the once-familiar environment of the seaside resort.   In some sequences, the filmmakers make use of obtuse angles to signify Mary’s sense of dislocation, shooting the actors in disorienting high-angle shots or framing them through the furniture. (Early in the film, Mary is shown playing the organ, the instrument’s pipes selfconsciously placed between the camera and the actress.) This is especially evident in the closing sequence of the film, as Mary finds herself chased through Saltair by the pack of ghouls. In these sequences, the filmmakers made use of a handheld, battery-powered Arriflex camera that was ‘traditionally used in news photography’; this camera allowed the filmmakers ‘to concoct elaborate camera moves without the use of expensive dollies or cranes’ (Crouse, op cit.: 37). The benefits of this method of shooting are evident from the outset of the film: following the car accident that opens the picture, the rescue attempt is shot in a cinema verité-style, with documentary-like footage of the car being pulled out of the river. Yet the dialogue scenes, in which Mary interacts with the other characters (in the doctor’s office, in the church, in her bedsit) are shot in a fairly conventional manner, often using the economical ‘two shot’. The juxtaposition between the ‘flat’ visual style of the expository sequences and the more elaborate visual style of the nightmare sequences allows the filmmakers to visually confirm Mary’s claim (to Linden) that ‘It’s funny. The world is so different in the daylight, but in the dark your fantasies get so out of hand. In the daylight, everything falls back into place again’.  All of the footage in Salt Lake City was shot in a single day (see Harvey, quoted in Weaver, 1999: 129). Further to this, the film used only one studio set: the doctor’s office, which was built at the offices of Centron, the industrial filmmaking studio where Harvey worked (see Harvey, quoted in ibid.). Everything else was shot on location, with the filmmakers shooting for one week at Saltair (Wilshire, 2007: np). This fast-and-loose shooting schedule works well for the film, although in a later interview with Tom Weaving, Harvey expressed regret at some of the sound design in the film and also noted that ‘one roll of film’ was lost that depicted ‘the ghouls coming out of Salt Lake. We had a scene of them coming out from behind pilings, out of the lake itself, white hands coming up and grasping the railings, black silhouettes coming in, getting ready for the Danse Macabre. It should have been very effective, but I never saw it’ (Harvey, quoted in Weaver, 1999: 135). Despite its originality, the film had some precedents, especially in terms of the depiction of the ghouls. For example, in Fearing the Dark: The Val Lewton Career (2003), Edmund G. Bansak points to the sequence in The Devil and Daniel Webster (William Dieterle, 1941) that depicts ‘the dancing dead’; Bansak cites this sequence as having a visual impact on the closing sequence of Carnival of Souls, in which Mary stumbles across the ghouls dancing together in the deserted dancehall at Saltair (330). Likewise, the sunken-eyed ghouls visually resemble the mechanical marionettes in Tales of Hoffman (Michael Powell, 1951), which Ben Hervey (in his BFI-published monograph on Night of the Living Dead) refers to as ‘deathly pale and dark around the eyes’, like the ghouls in Carnival of Souls and, later, Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (Hervey, 2008: 88).   However, Harvey’s major influences were European films, and in the commentary that accompanies this DVD release Kim Newman asserts that the film could be read as an independent American response to Jean Cocteau’s Orphée (1949). Newman contends that Carnival of Souls is an ‘accidental’ classic of the horror film. He argues that the film has more in common with the work of European ‘art’ filmmakers such as Jean Cocteau and Ingmar Bergman than with the traditional horror film. However, the way in which it was distributed in the US (on a double-bill with The Devil’s Messenger) led to a perception of the film as a ‘lowly’ horror picture; its pigeon-holing as a horror film has also been cemented by the way in which so many later horror pictures have adopted the movie’s visual ‘vocabulary’. Likewise, in Cutting Edge: Art-Horror and the Horrific Avant-Garde (2000) Joan Hawkins asserts that ‘if Dementia (Daughter of Horror, 1955) or Carnival of Souls (1962) had been made in Europe, the films would be considered art, or at least art-horror, films [in the manner of Georges Franju’s Les yeux sans visage (Eyes Without a Face, 1960)] instead of drive-in classics’ (27).

Video

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. The monochrome image is soft but not unwatchable. There is one curious instance of picture roll (at 16:36).

In 1962, the distributor Herts-Lion cut the film so they could fit it onto a double feature. The film was edited for its theatrical release by Herbert Strock, the director of The Devil’s Messenger (the film that Carnival of Souls was partnered with); Strock excised about 9 minutes of footage (see Harvey, quoted in Weaver, 1999: 137). Some of this footage was restored for the film’s rerelease in 1989. Although this expanded version of the film is often marketed as a ‘director’s cut’, it is in fact a restored version of the film that reinstates some (but not all) of the footage cut by the distributors in 1962. Harvey’s original ‘director’s cut’ was somewhat longer, running around 90 minutes in length (see Newman’s comments in the commentary). This DVD contains the longer restored version of the film, which on this DVD runs for 82:52 mins (PAL). The film seems to be a standards conversion from an NTSC source, as its running time is almost commensurate with that of Criterion’s NTSC release of this longer restored edit of the film (83:28 mins). The Criterion release of the restored edit also has a much sharper and more balanced image.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel monophonic track. This is sometimes soft and muffled, but it’s perfectly acceptable: dialogue is never inaudible. On the other hand, it’s a big step down from the Criterion release of the restored edit, which has crisp and well-rounded sound throughout. There are no subtitles.

Extras

The disc includes some contextual material: - A trailer (2:18) for the film promises ‘a new dimension in picture-making’. The trailer describes Mary as ‘ever-watched, tormented. Either it’s her neighbour, desirous of her physically, watching her with his leering eye, or it’s the evil eye of “the man”, the man who taunts her, the man who wants her’. The trailer explains that Mary ‘whirls between the real and the unreal, trying to cling to life’. - An audio commentary with Kim Newman and Stephen Jones. Newman refers to the film as ‘a minor classic of the horror movie genre’ and of ‘the independent American art movie genre’, whilst Jones expresses that he’s not a big fan of the film but recognises its significance for many viewers, confessing that ‘It has a mood and atmosphere about it’ that is unlike most other American horror films. The commentary is chatty and doesn’t seem to be closely-scripted; Newman and Jones offer some interesting critical reflection on the film and bring their usual encyclopaedic knowledge to the commentary track, bouncing ideas off one another and clearly enjoying themselves. There are little to no periods of silence, and the two contributors have clearly done their research. Interestingly, Jones contentiously asserts that he feels the film plays better in its abbreviated version. Jones notes that that in re-editing the picture for the distributors Herts-Lion, Herbert Strock removed one of the scenes that presented a conversation (between the doctor and Mary’s landlady) that took place away from Mary’s point-of-view; Jones argues that the film’s sense of perspective is therefore more consistent in the shorter edit of the film.

Overall

Even after almost fifty years, Carnival of Souls is still a haunting experience, tapping into our almost primal (and universal) feelings of alienation and disorientation, the sense of ‘not belonging’ to the world that we all experience at one time or another. Without wishing to resort to anecdotes, my first encounter with the film was via its screening on BBC2’s MovieDrome in the early 1990s; the premise of the film and some of the images from it haunted me for several years, until I managed to revisit the film. The film is a little rough around the edges, but that is part of its charm. The scenes filmed at Saltair are striking and effective and the appearances of the ghouls are suitably unnerving; but despite this, as Kim Newman notes on the commentary that accompanies this DVD release, Carnival of Souls is as much an attempt to ape the European art picture as it is a horror film. This DVD release contains the longer edit of the film, with footage restored for the film’s rerelease in 1989. However, the DVD appears to contain a standards conversion from an NTSC source, with all the ensuant problems associated with that practice, including an especially soft image and some motion blurring. Furthermore, the film’s audio is somewhat muffled. On the whole, the presentation of the film is certainly a step down from the Criterion release of the restored version, which it should be noted also contained the shorter edit of the film that was put together by Herbert Strock, along with a bevy of contextual material (including interviews with Clifford and Harvey, some of Centron’s industrial films, 45 minutes-worth of silent outtakes and a documentary about the 1989 rerelease). However, this new release from Network contains a new audio commentary by Kim Newman and Stephen Jones. This commentary track is lively and well-presented, and ardent fans of the film may wish to ‘double dip’ in order to acquire it. Newman and Jones repeat many of the established facts about the production of the film, but they also offer some unique critical insight into the movie and its importance. It’s just a shame that the presentation of the film is so much weaker than that of the Criterion release; had this DVD release contained a more impressive presentation of the film rather than a mildly disappointing standards conversion, I would have been much more enthusiastic in my recommendation of this particular release of one of the most-loved independent American horror films of the 1960s. References: Bansak, Edmund G., 2003: Fearing the Dark: The Val Lewton Career. London: McFarland Cox, Alex & Jones, Nick, 1993: Moviedrome: The Guide 2. London: British Broadcasting Corporation Crouse, Richard, 2003: The 100 Best Movies You’ve Never Seen. ECW Press Hawkins, Joan, 2000: Cutting Edge: Art-Horror and the Horrific Avant-Garde. University of Minnesota Press Hervey, Ben, 2008: BFI Film Classics: ‘Night of the Living Dead’. London: British Film Institute Ruffles, Tom, 2004: Ghost Images: Cinema of the Afterlife. London: McFarland Skrdla, Harry, 2006: Ghostly Ruins: America’s Forgotten Architecture. Princeton Architectural Press Weaver, Tom, 1999: Return of the B Science Fiction and Horror Heroes. London: McFarland Weaver, Tom, 2003: Double Feature Creature Attack. London: McFarland Weaver, Tom, 2004: It Came From Horrorwood. London: McFarland Wilshire, Peter, 2007: ‘Dead in the Water? Dream and Reality in Carnival of Souls’. OffScreen, 11(4). [Available online.] http://www.offscreen.com/biblio/pages/essays/carnival_of_souls/ Worland, Rick, 2007: The Horror Film: An Introduction. London: Blackwell For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|