|

|

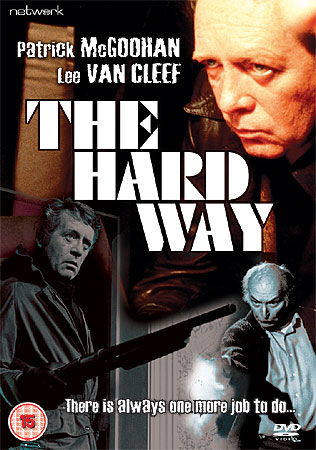

Hard Way (The)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (1st March 2009). |

|

The Film

Produced for ITC and starring Patrick McGoohan and Lee Van Cleef, The Hard Way (Michael Dryhurst, 1979) is a dark and solemn thriller. The film was originally to have been directed by Richard Tombleson, who along with Kevin Grogan wrote the screenplay. However, after reputedly coming into conflict with star McGoohan, first-time director Tombleson was fired and replaced by Michael Dryhurst. Dryhurst had previously worked as an assistant director for filmmakers such as Michael Winner (on I'll Never Forget What's'isname, 1968, and Lawman, 1971) and Mike Hodges (Pulp, 1972), and in this film there are elements of both Winner’s and Hodges’ work: like Hodges’ Get Carter (1971), The Hard Way focuses on a stoic, laconic hitman who goes rogue, breaking away from the criminal fraternity; and like Winner’s 1970s crime pictures such as The Mechanic (1971) Dryhurst’s film alludes strongly to the conventions of the then-popular European thrillers. Focusing on an Irish hitman named John Conner (McGoohan), The Hard Way opens moodily with Conner taking position in an abandoned building. Using a silenced rifle with a telescopic sight, Conner assassinates a man who steps out of a nearby car. Silently packing away his rifle, Conner leaves the building. Meeting another man at Euston Station (where the shared nationality of both men is signalled by their choice of Irish whiskey), Conner asserts that ‘You can tell them that’s the last’.   On the journey back to Ireland, Conner pulls a cheque from an envelope: he’s been paid £25,000 for the job. During the ferry crossing, he writes out a cheque for £11,000 to Kathleen Conner. Kathleen (Edna O’Brien) is Conner’s estranged wife; it is revealed that Conner has left his wife and their two children, as he is seemingly unable to function in a domestic setting. Waiting outside Kathleen’s home, Conner waits until Kathleen leaves; in Kathleen’s absence, Conner enters the house and leaves the cheque in a prominent place. He then takes his shotgun from the cupboard in which Kathleen has kept it, and he returns to his isolated cottage in the Irish countryside. There, he spends the night alone in a cell-like room. The next day, McNeal (Van Cleef) arrives at Dublin airport. McNeal has a job for Conner, even though he has been told that Conner wishes to retire from his work as a hitman. In response to this news, McNeal simply claims that ‘He’ll do it for me’. Meeting Conner in a pub, McNeal reminds him how difficult it is for men like them to leave the criminal life. ‘Come off it, John. Men like us don’t retire’, McNeal dryly asserts. ‘Don’t we?’, Conner asks sarcastically. ‘No, we stay in the action. We stay alive. You’ve been in the woods too long. Be good for you to get back to work’, McNeal tells him. Offering Conner $40,000 for a ‘job’, McNeal reminds Conner, ‘Have you forgotten it was me who pulled you off the skids when your wife kicked you out? If it hadn’t been for me, you would have skidded all the way to the grave’. When Conner boasts ‘I don’t owe you a damn thing’, McNeal asks him ‘Are you sure?’ Conner turns down McNeal’s offer of a job and returns to his cottage. Later, two men arrive at the cottage and make a veiled threat against Kathleen. Conner has no option but to accept McNeal’s job: he is to assassinate a priest. After accepting McNeal’s offer, Conner is told by McNeal, ‘You’re doing the right thing, John. Family life isn’t for us. Now, you get this job done and we’ll talk again: there’s plenty of action out there’. However, Conner tells the other men that he needs time to set up his equipment, and the film painstakingly shows Conner recalibrating the sight on his rifle and taking target practice in a disused quarry.  In his hotel room in Paris (where the hit is to take place), Conner tears up the cheque, symbolising his dissatisfaction with the way in which he’s been railroaded into accepting this new ‘job’. He abandons the job, fleeing from McNeal and his crew and returning to Ireland. Conner ensures the safety of Kathleen by visiting her in the night and sending her away. McNeal sends a group of men to assassinate Conner, but when they fail McNeal decides to do the job himself, leading to a showdown in an abandoned countryside retreat. The opening sequence of The Hard Way is strikingly effective. Completely silent, except for ambient sound and the ‘phfft’ of the silenced rifle as it fires, the sequence immediately establishes Conner as a coolly-efficient hitman. His professionalism is signalled through the way in which, after the hit has been completed, he silently and unhurriedly packs away his rifle before leaving the empty building in which he has taken position. In its relatively detailed depiction of the work of a professional killer, its focus on the theme of honour and its slowly confident approach to narrative, The Hard Way is very much a European-style minimalist thriller. Interestingly, Jean-Patrick Manchette’s 1981 novel La Position du tireur couché/The Prone Gunman offers a narrative that reads like a detailed pastiche of The Hard Way. Manchette’s novel focuses on a French hitman, Martin Terrier, who completes one last job on British soil before planning on leaving the criminal life behind him. Eventually, Terrier is railroaded into taking on another job but, like Conner, he deliberately sabotages the hit and then seeks revenge on his employer, building to a climax that takes place in an isolated country retreat in the French countryside. Like other English-language thrillers of the 1970s (for example, Michael Winner’s The Mechanic, 1971, and Walter Hill’s The Driver, 1976), The Hard Way calls to mind the key French thrillers associated with the nouvelle vague, including Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samouraï (1967) and Le Cercle rouge (1971). Like Jef Costello (Delon) in Le Samouraï, Conner has extricated himself from society and is silent for long stretches of the film; the comparison with Delon’s character is reinforced visually when, after returning to his cottage in the Irish countryside, Conner is shown (like Jef in the opening sequence of Le Samouraï) in his cell-like bedroom, lying silently but awake on the bed. Like Melville’s pictures, The Hard Way also makes heavy use of the ritualistic ‘cinema of process’, spending a good deal of time focusing on Conner’s preparations for his ‘job’: for example, his patient recalibration of the rifle’s telescopic sight is shown in detail.  The film uses an interesting device whereby the main narrative is intercut with isolated shots of Kathleen who, in a dark cave-like environment, narrates the film. These shots are placed into a narrative context at the end of the film, but they have a curiously Brechtian effect, distancing us from the narrative and encouraging us to reflect objectively on it. The narration provides a female perspective on what would otherwise have been an entirely masculine-centred tale of violence and revenge; Kathleen’s comments on her former husband’s work encourage us to see Conner in a different light, discouraging us from easy identification with him.   Kathleen’s narration first appears as Conner is on the ferry home to Ireland. Her sentences are clipped and gnomic, and in this first instance they are accompanied on the soundtrack by stereotypically Irish non-diegetic fiddle music. She tells us, ‘I knew he’d come back one day. Not to me, but to Ireland. I dreaded it. He always brought trouble. He wanted to change. Every time was the last time; there were so many last times. He couldn’t change’. Later, Kathleen reflects: ‘Thank God it’s finished: I’d seen the last of him’. Although this device is, on this first appearance, implemented in a slightly awkward way, as the film progresses the cutaways to Kathleen and her narration become more effective and, as noted above, become almost Brechtian. At one point, she reflects on Conner’s profession, reinforcing the monastic solitude in which he lives and, intriguingly, drawing parallels between Conner and the target of his latest job, the priest in Paris: ‘He was very gentle with [the guns], you know. In a way, he could have been a priest; I often said that’. Again, this aspect of Conner’s character seems heavily indebted to the solitude of Jean-Pierre Melville’s protagonists, from Jef in Le Samouraï to Silien (Jean-Paul Belmondo) in Le doulos (1962). Perhaps surprisingly, The Hard Way was, like Le Samouraï, shot by Henri Decaë, the highly-respected French cinematographer who, thanks to his work with both Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut, is closely associated with the French nouvelle vague. Decaë’s cool cinematography makes especially great use of the beautiful Irish countryside. It is this countryside with which Conner is associated: he is metonymically connected with rural Ireland, signifying his status as a force of nature. When McNeal sends three men to Conner’s cottage, he warns them: ‘His place is in the middle of nowhere. Rugged countryside: mountains, rocks, forests. He knows every inch of it like the back of his hand, and he’ll be ready for you. Don’t underestimate him. Conner will be playing the game he likes best. He’s got all the advantages, except numbers. But he’ll seem like an invisible army. Everywhere you’ll expect him and always where you don’t want him’.   The film builds to an inevitable, interestingly-filmed and downbeat climax that is reminiscent once again of Jean-Pierre Melville’s crime thrillers and Mike Hodges’ Get Carter; however, in its representation of the countryside retreat in which McNeal and Conner do battle as a funhouse of sorts (where McNeal has booby-trapped doors and laid tripwires across hallways), the sequence also brings to mind the disorienting funhouse climax of Orson Welles’ film noir The Lady From Shanghai (1947). As with Jean-Pierre Melville’s thrillers, the climax of the picture seems to suggest that the fate of the characters is already mapped out; as such, The Hard Way is a picture that exhibits an icily deterministic worldview.

Video

The Hard Way is presented in a fullframe ratio of 1.33:1. Originally produced for television, the film was distributed to cinemas, where it would most likely have been matted to 1.85:1 or thereabouts. The fullframe image contains a good degree of headroom, suggesting that the picture may have been shot with cinema distribution in mind: there is enough space at the top and bottom of the frame to suggest that the film could be quite comfortably matted for cinema exhibition, and the visuals seem to have been composed with this factor in mind.

The image is very clear and crisp. Colours are vibrant; for the most part, the visual palette is dominated by earthy browns and greens.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel monophonic track. This is clear and problem-free. There are no subtitles.

Extras

Some minor contextual material is included: - a trailer (2:32), which emphasises the presence of McGoohan and Van Cleef; - a stills gallery (1:09) containing promotional artwork and behind-the-scenes images.

Overall

The Hard Way is an exciting and subtle minimalist thriller in the European style. It makes excellent use of its locations, and viewers will recognise many of these from other films: for example, at one point Conner has a rendezvous with Devane (Joe Lynch) in Toner’s, the traditional Irish pub on Dublin’s Baggott Street in which Sergio Leone filmed the flashback sequences for Giù la testa (Duck, You Sucker, 1972); the sequences set around Conner’s cottage were filmed at the beautiful and ethereal Luggala Estate, where director John Boorman (the executive producer on this film) shot parts of Zardoz (1974) and Excalibur (1981).

A thought-provoking and low-key thriller, The Hard Way is required viewing for fans of both Van Cleef and McGoohan, and until now the film has been very difficult to obtain. Network’s release, which contains a lovely transfer of the movie and some minor contextual material, is very welcome; for fans of minimalist thrillers, this release comes with the highest recommendation. For more information, please refer to the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|